Ferdinand Berthoud was born in 1727 in Plancemont, a village in Switzerland’s Val-de-Travers that is located just five kilometers from Fleurier. Fleurier, of course, is a village that is home to some of the world’s best high-end brands and independent creators: Chopard, Parmigiani, Kari Voutilainen, and Bovet to name a few.

Berthoud completed his apprenticeship with his brother Jean-Henri, a pendulum maker, after which he went to Paris to set up a business in clocks in 1745. It was here that his reputation as a maker of marine chronometers par excellence was established – he made his first chronometer in 1754.

Berthoud was officially awarded the title of master clockmaker in Paris in 1753. He was appointed clockmaker to the French navy in 1762 and clockmaker to the king in 1773 (which at the time was Louis Philippe).

He became a member of the Institute of France and a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1764.

This pocket watch made by Ferdinand Berthoud in 1806 is on display at Chopard’s L.U.C.eum in Fleurier

Berthoud passed away in 1807, leaving behind a vast body of work in marine chronometers, clocks and watches, tools, scientific measuring instruments, and written publications including dozens of specialized books and treatises encompassing 4,000 pages and 120 engraved plates.

His most famous written work was Essai sur l’Horlogerie, which he completed in 1763, though he authored many others including Traité des Horloges Marines (1773), Histoire de la Mesure du Temps (1802), and the texts on watchmaking in the Encyclopedia of Diderot and d’Alembert.

Though he had married twice, he died childless. His business was taken over by his nephew, Louis Berthoud.

Marine chronometers

Berthoud is credited as one of the key pioneers in developing the chronometer, a term that today denotes an especially precise timepiece. To be called a chronometer, a timepiece must be certified by the C.O.S.C. (the Contrôle Official Suisse de Chronomètres/Official Swiss Control of Chronometers).

However, in eighteenth-century Europe there was no formal certification process to determine the accuracy of a timepiece. And accuracy was a real problem – even though accuracy was essential because chronometers were used as navigational instruments.

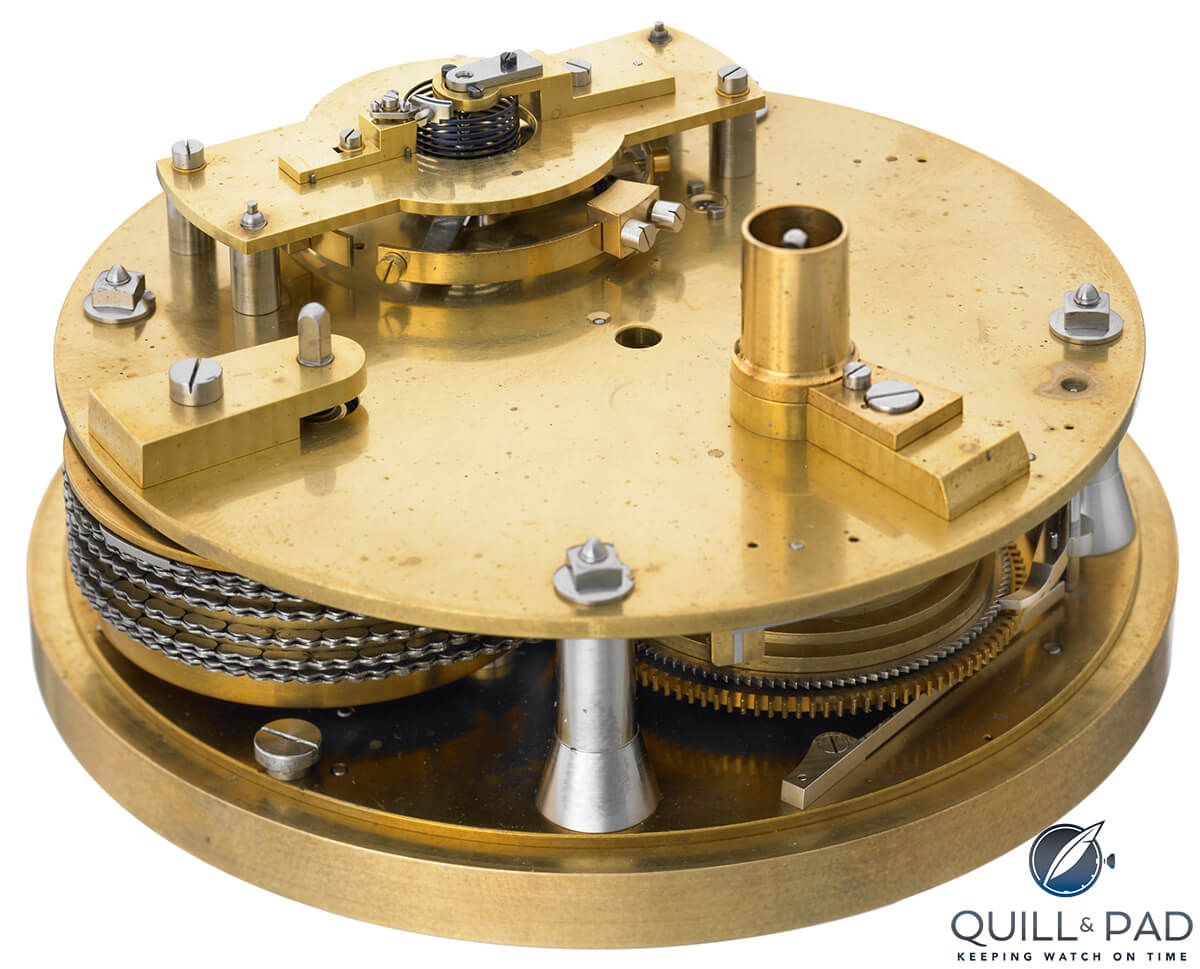

A marine chronometer from Berthoud’s workshop from 1850, now on display at Chopard’s L.U.C.eum in Fleurier

It was the wreck of four British navy ships and loss of 1,600 lives, which was caused by inaccurate navigational chronometers, put the need for accurate timekeepers into the spotlight. In response, British Parliament announced the Longitude Act on July 8, 1714, as a need for a better way to measure longitude was now apparent.

Precision being a must, the Longitude Act promised large rewards for anyone who “shall discover a more certain and practical method of ascertaining the longitude.” The reward for the successful invention was a true king’s ransom, 20,000 pounds Sterling, which would be valued at several million dollars today.

This decree kicked off a flurry of research into the concept of the marine chronometer, with self-taught clockmaker John Harrison (1693–1776) legendarily presenting his H1 in 1735. This inventor of the marine chronometer won the quest with his H5, though his award was disputed for many years.

Thomas Mudge (1715–1794) invented the lever escapement that is still widely used today in Swiss and other fine mechanical timepieces, though it is known these days as the Swiss lever escapement due to the many changes and improvements made to it over the course of about 250 years – including by Berthoud.

The movement from a marine chronometer from Berthoud’s workshop from 1850, now on display at Chopard’s L.U.C.eum in Fleurier

Finding ways to improve upon the chronometers already invented by Harrison and Mudge was one of the key goals of horology in Berthoud’s day.

Berthoud and his great rival Pierre Le Roy, also at home in Paris, furthered the cause immensely.

Main inventions

Ferdinand Berthoud was the watchmaker to make the use of jewels (ruby and diamond) as bearings in watchmaking acceptable. Though this was something already initiated by Nicolas Fatio in 1704, it did not become common until Berthoud adapted it.

Berthoud also improved the self-compensating balance wheel and conducted considerable research, which he left behind in the form of his written works.

However, Berthoud is above all remembered – and even revered – for his invention of a spring-driven escapement, which appeared at about the same time as those of John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw.

Berthoud (and Le Roy) succeeded in developing especially precise chronometer escapements, which continued to remain in use until the end of the age of mechanical chronometers. Using the Frenchmen’s simplified components, Arnold created a robust chronometer design that would remain in use without great modification for about two more centuries – or as long as marine chronometers remained necessary to navigation at sea.

The movement from the Ferdinand Berthoud pocket watch from 1806, which is on display at Chopard’s L.U.C.eum in Fleurier

Enter Chopard

By now you’re wondering why I’m babbling on about a watchmaker who’s been dead for 208 years. Well, like all good things, he may be gone, but he has not been forgotten (particularly for his service to chronometric precision).

Back in 2006, Chopard co-president Karl-Friedrich Scheufele had quietly acquired the rights to this most revered name in horological history: Ferdinand Berthoud.

Scheufele intends to bring the memory of Ferdinand Berthoud back to life with homages to his substantial horological legacy. The new brand he has created, called La Chronométrie Ferdinand Berthoud, will be positioned at the very top of the Chopard group, focusing on exceptional timepieces manufactured in very exclusive numbers. (Read Chopard Resuscitates Historical Watchmaker To Create Ferdinand Berthoud Brand.)

“In acquiring La Chronométrie Ferdinand Berthoud in 2006, I wanted to be sure that one day a watch bearing this name would be worthy of the great master horologist who inspired it,” Scheufele explained, certainly also in reference to other modern brands bearing names of the great classic watchmakers with no visible relation to their respective work.

In 2006, Scheufele added a museum he calls the L.U.Ceum to Chopard’s Fleurier factory. This museum contains a number of pieces he has collected from the annals of watchmaking history, including pieces by Ferdinand Berthoud.

The next exciting chapter of Berthoud’s modern saga has unfolded. For full details please read Ferdinand Berthoud Is Reborn With FB 1 Thanks To Chopard’s Karl-Friedrich Scheufele.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] also enjoy: Ferdinand Berthoud Is Reborn With FB 1 Thanks To Chopard’s Karl-Friedrich Scheufele Who Was Ferdinand Berthoud And Why Should We Care? Chronomètre Ferdinand Berthoud FB 1, Winner Of The Aiguille d’Or At The 2016 Grand Prix […]

-

[…] First up from the wider world of watches, we have a discussion about a watchmaker of days gone by that you may not be aware of – Ferdinand Berthoud. Born in the early 1700s, Berthoud became a master clockmaker by 1753, and was a pioneer in the world of chronometers, which were becoming more and more important at the time for accurate marine navigation. He is also the man that is responsible for making the use of jewels in a movement acceptable and (now) commonplace. He also had one other rather important development that he was responsible for. For the details on that, as well as why Elizabeth Doerr is talking about a watchmaker from over 200 years ago, you’ll need to check out this article over at Quill & Pad. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Jewelled bearings were in use and “acceptable” years before Berthoud ever used them. Watch jewelling was rather common in England, but it was decades before anyone would make them on the Continent. Even Breguet had to get his from Arnold. Furthermore, many of Berthoud’s timepieces used rollers for the balance pivots and oil sinks for the train. Continental makers would not adopt jewelling on a large scale until the end of the 18th century, by which time Ferdinand’s nephew Louis had been in charge of the workshop for some time and had mostly taken over the business.

Additionally, while Berthoud did develop a practical form of the pivoted detent, one used by Breguet and very similar to the one used by Arnold, the spring detent was invented in England before it was developed in France.