When you think of fantasy and science fiction, what do you think of?

Some people envision spaceships and the final frontier, while others ponder dystopian futures. More still imagine planets like Arrakis from the Dune universe and wonder what its “spice melange” would have to offer.

I sometimes contemplate all of these, but I also allow my imagination to drift into the paranormal and early twentieth-century years of discovery – when the previous generation’s science fiction was being eclipsed by even grander ideas and inventions.

It was also during this time that many were still grasping at ages of superstition and fears past, thanks to an explosion of scientific advances combined with drastic war and social upheaval.

H.P. Lovecraft is a familiar name in this genre and period of scientific advance, and he provided a mountain of inspiration to later generations. Lovecraft also influenced stories of one of my favorite universes, that of “Hellboy.”

Originally created in 1993, the world of Hellboy begins in World War II and continues through to the modern day, documenting a demon summoned to earth by Nazi occultists aided by Grigori Rasputin.

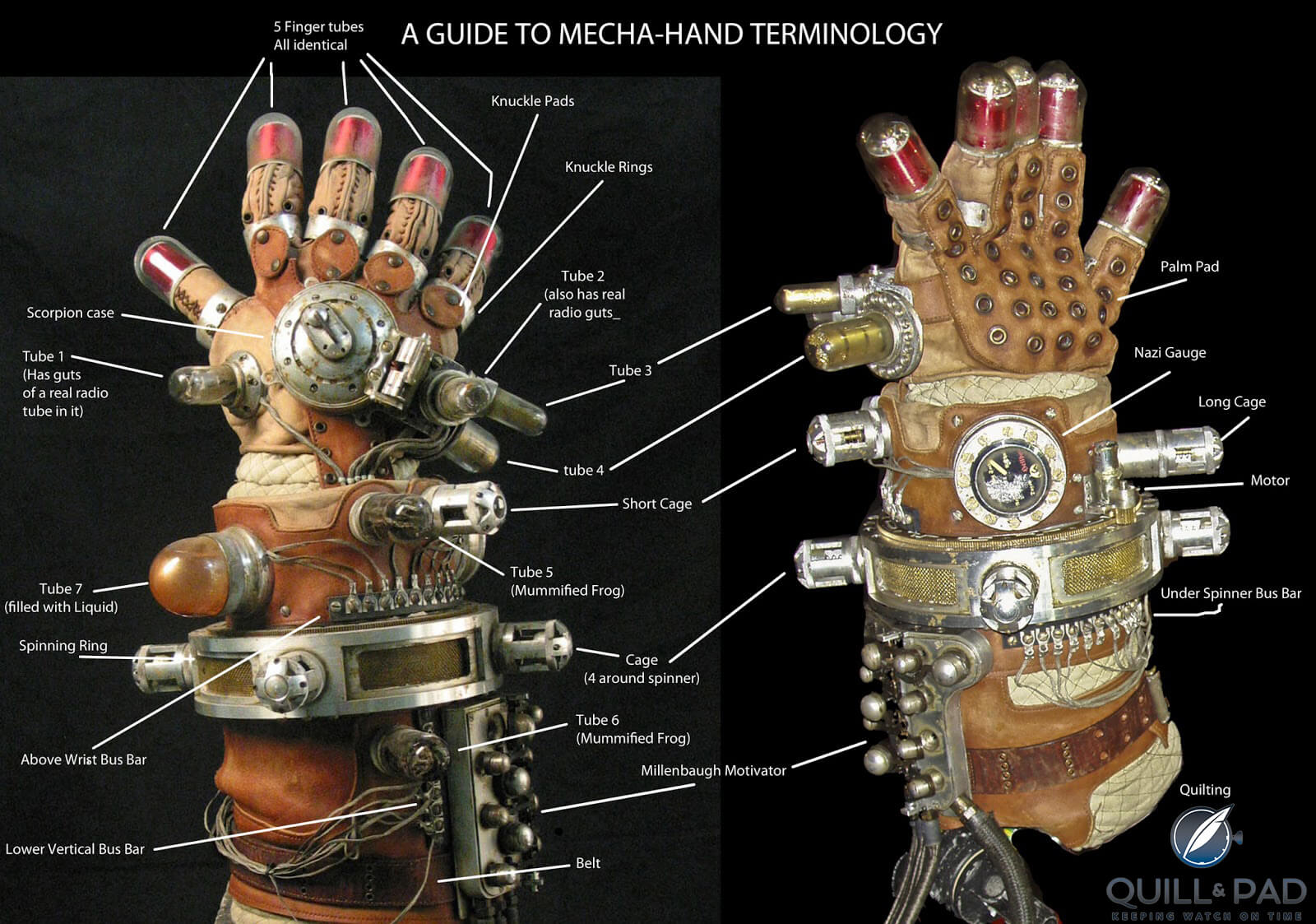

In the story that was also the loose basis for the major motion picture of the same name, Rasputin creates a mechanical glove that is more accurately a “paranormal steampunk portal opener.” It is one of the coolest props in the film and something I feel defines a specific style of early modern mechanical sci-fi.

Random connection

It is also the first thing I think of when I think of Nixie tubes. Funnily enough, the mecha-glove from Hellboy doesn’t actually have any Nixie tubes on it, but the array of vacuum tubes and liquid-filled glass tubes are analogous in technological progress and the invoked emotional response to me.

Both the mecha-glove and Nixie tubes are from a world before the modern digital age, a previous age that birthed all of our current technology.

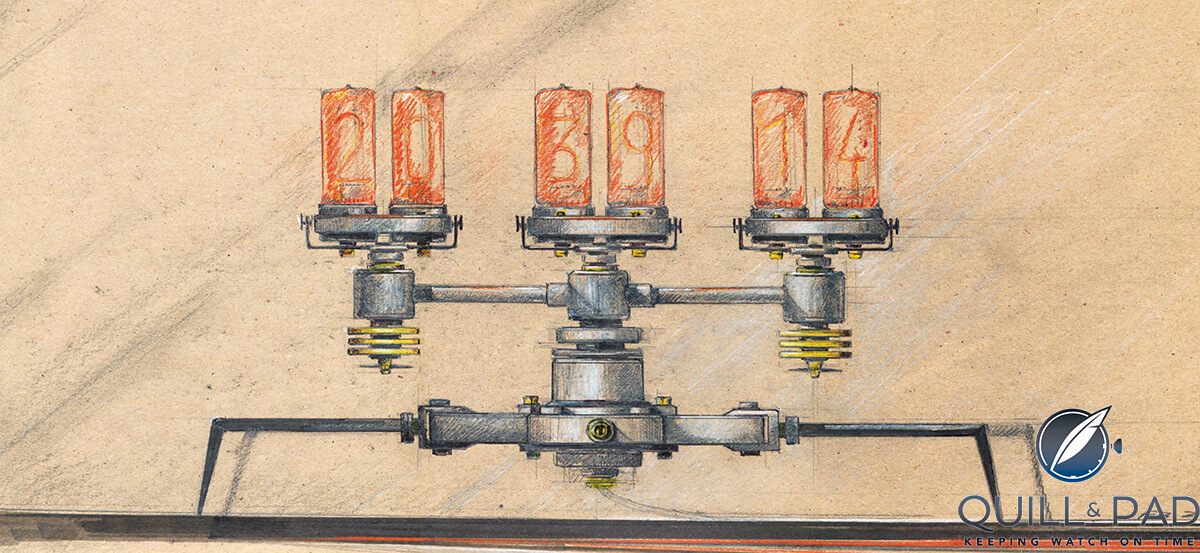

It is also the world that inspired the creation of Frank Buchwald’s latest creation for the M.A.D. Gallery, which is, of course, the Nixie Machine, a fantabulous clock featuring rare and giant Nixie tubes produced in the 1960s by the state-owned RFT in East Germany.

Buchwald’s digital clock is an imposing creation standing sixteen inches tall and measuring three feet in length. It contains 3.5 inch-tall bright orange Nixie tubes. And it exudes an overall steampunk feel.

I can imagine this clock in a variety of fictional settings from the worlds of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells to even Isaac Asimov.

But what in the heck are Nixie tubes really?

This question goes back to before Nixie tubes were invented as they were just a step in the creation of digital indication that began years before the mechanical means. Digital indication became increasingly technical as electronics became more commonplace.

Displays such as vacuum fluorescent displays, dot matrix, Numitron incandescent filament readouts, and seven segment displays were developed. Each worked in its own specific way and had its advantages and disadvantages.

Warning: science content ahead!

Nixie tubes are a special type of “complicated” (coming from a non-electronics guy) as they are considered a cold-cathode tube, which is basically a variant of a neon lamp.

The way that they work is different from a regular incandescent lamp (the standard light bulb we are used to where a wire filament glows, or fluoresces, in a vacuum) or even the more comparable neon tube (where all of the gas inside the tube fluoresces).

Inside of the Nixie tube is a stack of typographically designed numerals, 0 through 9, layered in a way so that the least amount of non-essential numerals will be in front of (and possibly blocking) the specific numeral in use.

A sample layer order from front to rear would be 6, 7, 5, 8, 4, 3, 9, 2, 0, 1.

These numerals also represent the individual cathodes, which means that a current flows out of each numeral.

In front of this stack of numerals/cathodes is a mesh screen, which acts as an anode, an electrode into which the current flows as electrons leave. The current wants to move from the numerals to the mesh screen.

The reason a mesh screen is used in place of a single point is so that the current moves as evenly out of the numeral cathodes as possible instead of arcing to a specific point. This allows for the current and incoming electrons to interact evenly with the neon surrounding the numerals/cathodes, causing it to fluoresce immediately around the shape – which results in brightly glowing number-shaped plasma.

The subtle science of this transition and the careful controlling of the phase change is where it gets really complicated to me. To keep all of the numerals/cathodes from glowing at the same time once a current is initiated, the system has a pre-bias voltage on the numerals, usually somewhere in the 50-volt range.

This means that all of the numerals have a small voltage applied to them and act as anodes when they are not grounded, compared to a numeral that is “on.”

This pre-bias voltage helps the high voltage on the mesh anode (around 170 volts) jump across the non-grounded numerals (now acting as anodes) to the selected and grounded numeral. This keeps only one numeral at a time fluorescing and provides a clear, clean plasma number.

Whew!

Okay, so with all of that science taken care of, you have a basic understanding of just why these Nixie tubes are so cool and why, upon finding a stash of such large tubes, the idea to make a clock was so enticing even now.

This project originates in an old Bulgarian army depot where Alberto Schileo, Nixie clock aficionado and friend to MB&F founder Max Büsser, discovered a cache of very large and extremely rare Nixie tubes in brand-new condition.

Nixie nerd side note: one of the largest known Nixie tubes is the Rodan CD47, which towers at more than 210 centimeters (8.5 inches).

The find made Schileo begin pondering the idea of a high-end Nixie clock and thought of MB&F and Frank Buchwald, who had already created Machine Lights for the MB&F MAD Gallery. Schileo contacted Büsser and the outcome of all of that is what you see here. Boy, is it something to see.

The Nixie Machine features six of the 90 millimeter-high Z568M Nixie tubes manufactured in East Germany at RFT (the state-owned Rundfunk- und Fernmelde-Technik, a conglomerate, known as a combine in Communist East Germany, of electrical manufacturers). The clock is made from about 350 components. The original prototype of the Nixie Machine took a little less than a year to design and construct.

All of the non-electrical parts are crafted in steel, stainless steel, and brass in two different combinations for two limited editions of six pieces each. The style is very clearly industrial, following the Buchwald’s approach to his lighting projects.

One thing to notice is that things come in threes where they can with Buchwald and his lighting projects: the triple mounts for the Nixie tubes, the insulator-inspired details underneath the tubes, the section mounts, and on the main support shaft all add to the feeling of high voltage and historical relevance.

More details

But most important is how it works. I have already provided a short rundown of how the actual Nixie tube works, complicated as it was. Fortunately, the clock itself is a bit more straightforward.

There are two receivers to guarantee accurate time and date should you not want to simply set it yourself, which you can do. The first is a GPS receiver and the second a DCF77 receiver, which receives its signal from Mainflingen, Germany, with a range of about 2000 kilometers (almost 1,250 miles).

If you were to buy this clock and take it out of Europe, then the GPS receiver would be your automatic time and date receiver.

The Nixie tubes are directly driven and individually controlled with power flowing to the cathode the entire time it is lit. This helps ensure a clean and steady power source.

But probably the most important key function that does nothing other (for you) than provide a show is the automatic cycling of all the numbers in the tubes.

The reason for this show is due to the fact that, as a clock, the tubes that don’t display the seconds will hardly move, and one of the tubes will only ever show a 0 or a 1. Because of the sensitivity to deposits or corrosion on the cathodes, the numbers must all be cycled to “burn off” any possible deposits.

The process of developing deposits is what is known as “cathode poisoning,” and the result is what can eventually kill a tube.

As micro particles cling to the cathodes, they will inhibit electron flow between the anode and the cathode numerals. This will appear as a dead spot or unlit portion of a number. The reason it will appear unlit is because the gas directly adjacent to the areas with deposits will not be made to fluoresce and the plasma shape will be uneven.

The Nixie Machine can be made to cycle through all the numbers at set intervals, and, honestly, it’s one of the most fascinating aspects of the entire clock.

Worth its weight in Nixie tubes

The Nixie Machine’s “presence” is what sells it upon first viewing, but given that these tubes (of which Schileo only found maybe two hundred) are as rare as they are, this machine isn’t just a contrived limited edition for no other reason than to bump up the price.

No, this is limited because the supply, as of yet, is small, technical, and most importantly, finite. Buchwald, Schileo, and MB&F have even set aside spare tubes for the owners when the tubes eventually (and they will eventually) stop working. No easy repair here, yet.

The design, construction, and technology in the Nixie machine are awesomeazing, and the sheer history behind the piece is astounding.

Just learning about this clock has given me a newfound appreciation of electronics (don’t tell anyone) and the ingenuity of the first half of the twentieth century. I definitely will be diving a little deeper into this mid-century technology to better understand where we came from. I think I’m going to go back and watch some sci-fi, and definitely some “Hellboy.”

For more information, please visit www.mbandf.com/mad-gallery and www.frankbuchwald.de.

Quick Facts

Base: 92 x 42 cm, choice of, burnished steel and brushed brass or stainless steel and brushed brass

Movement: circuit board and six Z568M Nixie tubes

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; date, night power down mode, alarm

Limitation: six each in burnished steel and brushed brass and stainless steel and brushed brass

Price: 24,800 Swiss francs