Today, more than ever, discerning between true innovations in watchmaking and sheer marketing fluff is no easy task. Are the two even mutually exclusive?

Earlier this year I was invited by H. Moser & Cie to attend a most atypical press conference in Zürich. The occasion was the first parabolic flight in Switzerland, during which Moser, along with its escapement-making sister company Precision Engineering, tested movements and components in zero gravity.

At the same occasion, H. Moser & Cie launched the new Pioneer collection, its most contemporary yet.

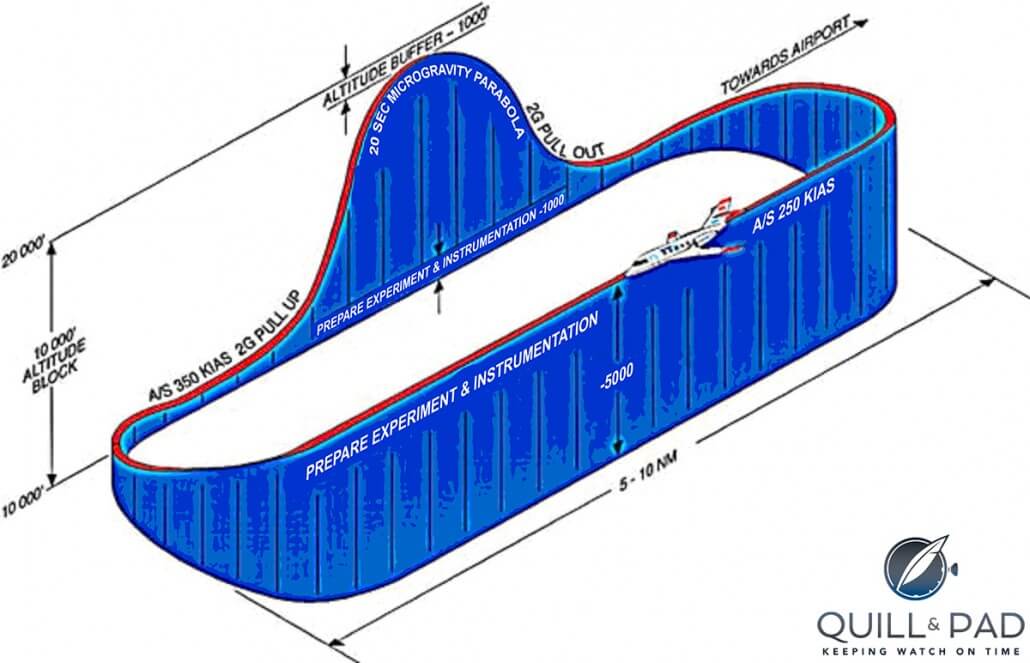

A parabolic flight, by the way, is defined by Wikipedia as, “A flight path used by aircraft to train astronauts in zero gravity maneuvers, giving them about 25 seconds of weightlessness out of 65 seconds of flight in each parabola. During such training the airplane typically flies about 40–60 parabolic maneuvers.”

As great as it was to get an early hands-on look at the Pioneer collection while the parabolic flight was underway, I was a bit skeptical about what the words “parabolic zero gravity flight” actually meant –if anything at all.

I mean, sure, being the first brand to test watches and/or movements in a weightless atmosphere has a nice ring to it, but the skeptic in me can’t help but wonder whether it was all just a way of giving the new collection a story to tell.

Groundbreaking or bunk? I recently caught up with H. Moser & Cie’s CEO Edouard Meylan to find out what this zero gravity business was all about.

Quill & Pad: Hi Edouard, thanks for taking the time to chat with me. I’ll get right to the point: why did H. Moser & Cie along with sister company Precision Engineering decide to take part in the first Swiss parabolic zero gravity flight? Was it just an occasion to make noise or is there real technical merit?

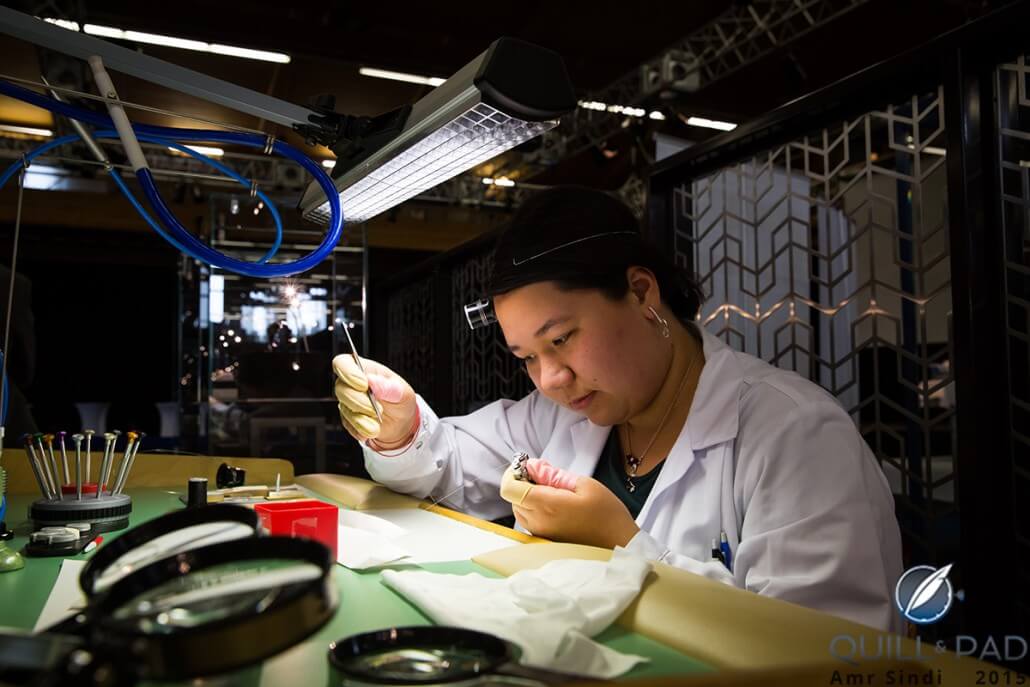

Edouard Meylan: It all started a few months ago. We had questions about how we could improve the quality of the products from our escapement specialist sister company Precision Engineering. One of the issues we face is that we have multiple clients with their own movements under development, who come to us to provide the escapements.

Our engineers then create simulation models, and if the escapement works in the model we produce it. One of the problems, of course, is that there’s always a difference between what our models show and how the escapement performs under real conditions. Every element, including the material, lubrication, or even just the way it’s manufactured and assembled, becomes a variable that a computer model can’t accurately account for.

One of the questions I asked is, “How can we better understand what creates the differences between theory and practical results?”

“Well, the only way would be to try and remove any mechanical constraints,” one of the engineers answered.

“How do we do that?” I asked.

The engineers started laughing and one of them said, “By going to space.”

That was a few months ago, and I thought, “Okay, that’s not going to happen.” And I forgot about it.

Not long after, I was driving to the office one day and I heard on the radio that University of Zürich was preparing a first parabolic flight in Switzerland. I didn’t know such a thing even existed, so we got in touch with the university and expressed our interest and needs for a specific kind of testing. They were pretty excited about it.

We then contacted Witschi to make the necessary instruments for the tests. These were able to test up to ten movements in parallel, so we basically tested the same movement with ten different escapement configurations using different materials, hairsprings, curves, double hairsprings, and so on; variations of the key combinations and how they behave differently in both hyper and zero gravity environments, how precise they are, and, most importantly for us, how closely to the model simulations they perform.

A parabolic flight doesn’t offer absolutely zero mechanical constraints, as you would have to remove the air and create a vacuum, but we went as far as we could with our resources.

As to the marketing side, well, we’re a small company, so once we had the possibility to go up there and conduct the tests, we asked ourselves, “How can we make the best use of this opportunity?”

During the actual parabolic flight, our engineers and I didn’t have much to do except enjoy floating around in zero gravity. So we thought that would be a great environment to launch the Pioneer collection, our new “everyday” watch line. That’s really the only marketing and PR side to the whole project.

Q&P: But is one flight and a couple of minutes in zero gravity really enough to test different escapements?

EM: It’s true that five and half minutes might not seem like much, but it gave us some really interesting indications and things that we can explore further.

We are working on new processes to form the curves. When you form the curves by hand, you create micro ruptures in the material, so we’re working on new systems using new processes as well as materials.

It all requires further research. So it’s not going to deliver final results immediately after, but it has permitted us to work on several patents for curves and hairsprings.

We’re actually planning on doing more flights with Novespace, and not just in Switzerland.

Q&P: Were the results what you and your teams were expecting or hoping for?

EM: Obviously I can’t share the results, but I will say this: it’s not easy to produce hairsprings. Most of what we see today has been developed centuries ago, like the Breguet terminal curve. And little has been done to improve on this. With Precision Engineering, we aim to become a value-adding feature in our clients’ watches, like “Intel inside.”

Today we’re conducting a lot of research and constantly improving our escapements. A few years ago, Precision Engineering wasn’t known to make particularly reliable products. But already today we have a lot of great loyal brands that we supply.

We’ve already proven with the double hairsprings that we can produce something that outperforms a tourbillon, which is marketed as being the benchmark of accuracy and performance even though this is far from the case.

So you can expect some evolutions to the double hairspring and flat curves. You need two perfect hairsprings in each escapement, which is impossible depending on how you fix them, create the curves, and so on. When you have gravity, it sort of decompensates for any small variances, but in zero gravity we are really able to gauge how much of an impact these minute differences have.

Q&P: Not long after H. Moser & Cie took to the skies in Switzerland’s premiere zero gravity flight, another brand followed suit, though in all fairness it was probably in talks with Novespace at the same time as Moser. Would you say that zero gravity will be an avenue more and more watchmakers will head to for research and testing?

EM: Frankly, I think zero gravity testing is only relevant for watchmakers or suppliers who make their own escapements and hairsprings, because otherwise you don’t master the element that is most important for a movement’s accuracy. So what’s the point? It doesn’t really apply to a company like Nivarox, whose hairsprings are quite standardized and produced on a more industrial scale.

What we do is prepare customized solutions for our customers; there’s nothing standard. Maybe one of the handful of others will follow suit, but I’m not sure. It’s a considerable investment, but there’s also a lot of raw data to process afterwards.

Keep in mind that these were tests for and by Precision Engineering.

H. Moser & Cie used zero gravity flights to test the effects of an absence of gravity on regulating systems

Q&P: During the press conference, you briefly mentioned that the zero gravity tests would allow H. Moser & Cie/Precision Engineering to go “beyond the Breguet terminal curve,” which is quite a statement. Can you tell us a little bit more?

EM: There are three main aspects we’re developing. One is the double hairspring, as I mentioned earlier.

Second, is the shape of the curve and how we shape it, which so far remains quite rudimentary and involves a lot of mechanical stress. We have patents being published in the coming months with pretty innovative ways of improving this.

Then there are the actual materials we use. Paramagnetic is the future, but that’s all I can say for now.

Q&P: Can we expect to see these developments making their way to H. Moser & Cie watches in the not-too-distant future?

EM: If all goes according to plan, perhaps as early as next year.

For more information, please visit www.h-moser.com.

Quick Facts

Case: 42.8 mm; 18-karat red gold and black DLC-treated titanium

Dial: sunburst argenté, red gold fumé, or ardoise fumé

Movement: automatic Caliber HMC 230

with three-day power reserve

Functions: hours, minutes, sweep seconds

Price: $22,900

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

I guess as a small company, you try to get free press whenever you can. But with Moser its very obvious they try to take advantage of any public opportunity.

Very nice watches that are now overpriced.