Did you know that grasshoppers are the bullies of the insect world? They are known to pick on smaller insects, even forcing ants to do manual labor on their behalf. And sometimes they have serious aggression issues.

Grasshoppers have even been known to kidnap and hold ant royalty ransom in order to ensure compliance with their demands. At least the grasshoppers in the 1998 animated Pixar film A Bug’s Life did. And I’m pretty sure it was scientifically accurate.

Okay, I’ll admit that was just a ruse to interest you a bit more in grasshoppers. But I promise that if you read on I will deliver some very interesting bits of knowledge about grasshoppers in my own way.

In doing so I am going to get all kinds of nerdy about a new(ish) escapement concept that Parmigiani Fleurier, Vaucher Manufacture, and the Swiss Center for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM for short) have been developing over the last decade. The group has finally released an encased concept called the Senfine.

The name is rather appropriate since the idea for this escapement concept came as a way to reduce friction and drastically extend the power reserve of the average watch.

Meaning “eternally” in Esperanto, the word Senfine imparts the understanding that it should last forever (we’ll get to that) and that it should make the regulator more isochronal, meaning each beat of the balance takes exactly the same amount of time.

Take this into consideration: the original reason for creating the Esperanto language was a desire to make a universal language that was an easy and trouble-free way for people around the globe to communicate with each other. The choice to use a word from that as-good-as-defunct yet poetic language seems strangely fitting.

But enough about the name, let’s look at the Senfine concept, where it came from, what it does, and why it is probably one of the more important horological inventions of a mechanical nature in my lifetime.

The Senfine concept is the continuation of an invention conceived by Pierre Genequand, who worked as a physicist for CSEM before retiring in 2004. His experience with flexible joints and their frictionless properties is where the genius sprouted, evolving into where the Senfine concept is today.

Silicon

The basis for the entire concept hinges on the advances made in silicon fabrication techniques in the last couple of decades. Silicon has some incredible properties, not the least of which pertains to its inherent strength and flexibility.

Even though silicon can be a very rigid metalloid, when the atoms are organized in specific ways or combined with other elements, different properties can be achieved.

A combination of elasticity, rigidity, and ultra-low friction surfaces is usually the goal for components manufactured for watch movements. But in most cases the parts are designed to be replacements for traditional components that were originally designed and engineered to be optimized for their original mechanical properties.

So Genequand started over from scratch, and thanks to his almost complete lack of knowledge about watches and watchmaking he managed to develop a system around the inherent properties of silicon and his knowledge of flexible joints.

It should be stated that he clearly must have had a handle on the concept of the mechanical timekeeper to have thought to improve the regulation system. Regardless, the result was a mechanism that took extreme advantage of the flexibility of a thin silicon blade and the super smooth surface that processes like Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE) can achieve. This is where the grasshopper I spoke of comes back in.

Since Genequand was not familiar with watchmaking techniques and the intricacies of different escapements, he designed based on the properties of silicon and inadvertently came up with a system remarkably similar to the classic John Harrison grasshopper escapement.

But it is not, by definition, a grasshopper escapement, and the details will make that very clear given that there are almost no recognizable “watch” parts save two or three.

From the oscillator, out

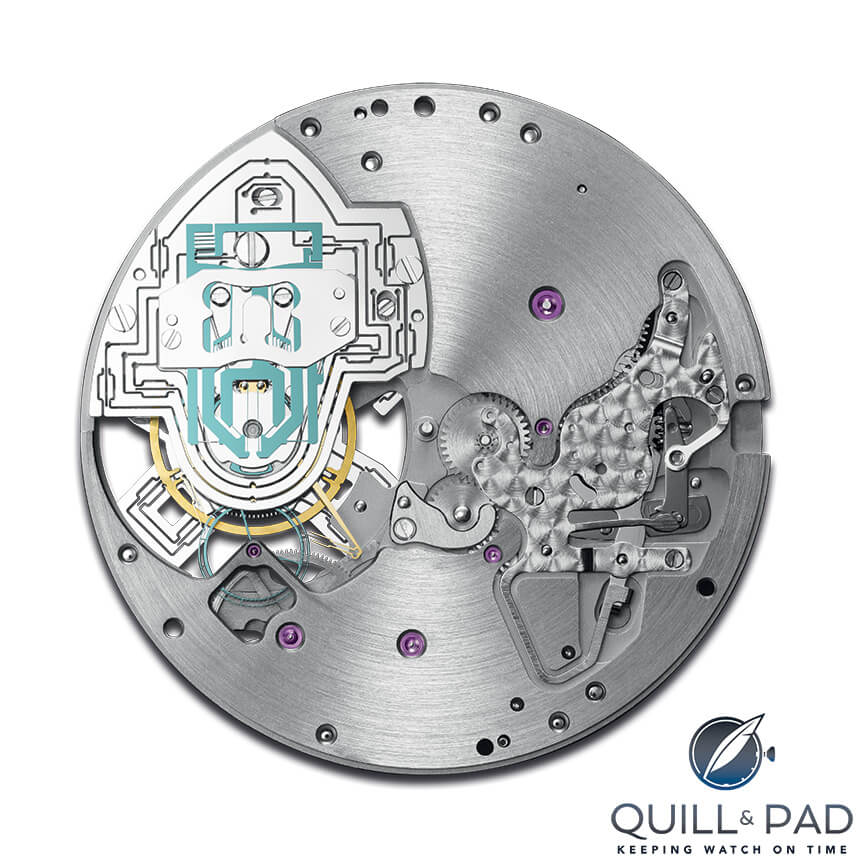

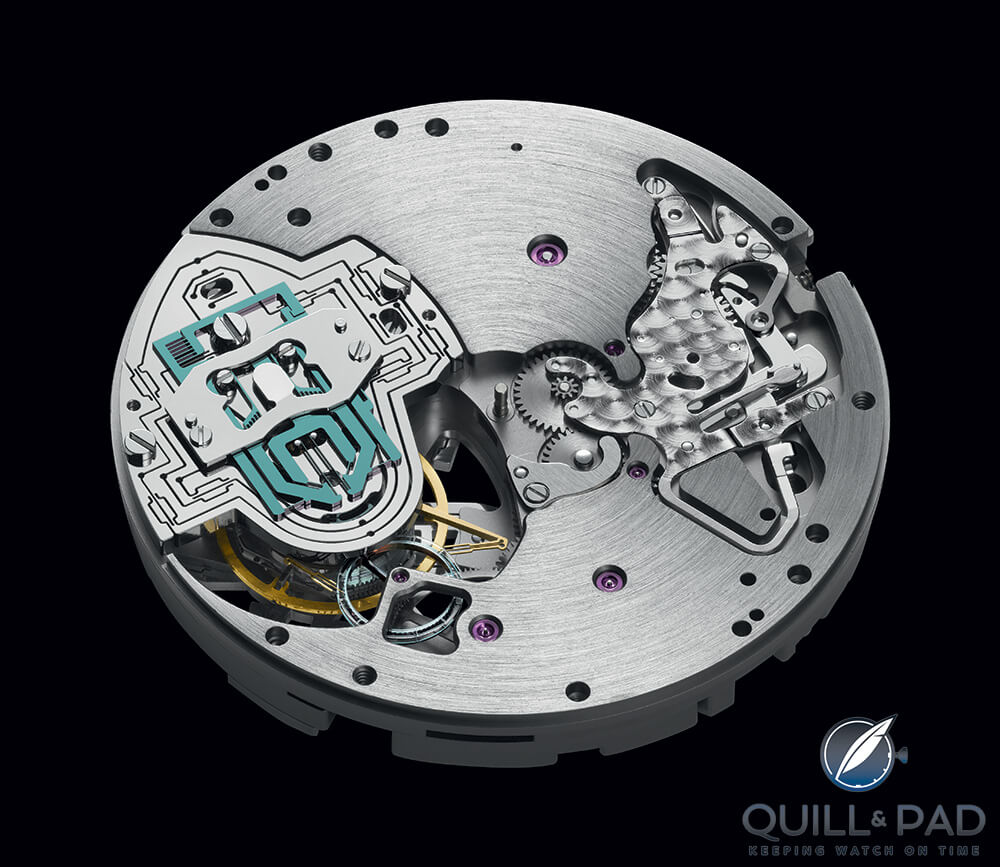

Beginning at the true heart of the system we have a gold balance; this is the first of two familiar components that have been turned on their heads. The gold balance is basically just a ring that is attached to a much more complicated and high-tech silicon component acting as a pivot/hairspring.

The gold balance ring is pressed over the central silicon component to form a slightly wonky balance assembly referred to as the oscillator.

Clever names aside, in that oscillator assembly four embedded gold weights act as eccentric timing weights. These weights are miniature rings held into the oscillator assembly thanks to minute features that provide a spring clip-like attachment.

None of this would be physically possible without the high-tech fabrication techniques available today.

As I mentioned, the silicon center component for the oscillator assembly acts as a pivot/hairspring. This is achieved by overlapping and crisscrossing (but not touching) guide arms, which allow the oscillator to twist a small amount with what is called a virtual pivot.

This means that the two counteracting arms create a rotational movement around a point in space that is pretty much the same every time. This virtual pivot is so named because there is no structure around which it rotates and no defined pivot axis; it is simply rotating in whatever way best fits with the geometry of the oscillator arms.

This feature creates three major differences between the Senfine’s balance and a standard one.

First, it eliminates friction from the balance staff and jewels since it pivots in mid-air; second, it allows for a larger amount of movement in the oscillator (in left, right, up, and down directions) saving it from bumps and bruises, or worse, a broken balance staff; and, finally, it limits the rotation from around 300 degrees in a traditional balance wheel down to 16 degrees total amplitude.

This is the point where you spit out your coffee and exclaim, “Amplitude of sixteen degrees!!”

Holy moly!

Yup, the total amplitude is only 16 measly degrees, almost twenty times less than all those wild and loose balance wheels out there.

Heck, that is less rotation than occurs by the hour hand in one hour. But the oscillator assembly isn’t the only thing responsible for that amplitude; the amplitude is a factor of many other aspects of the Senfine regulator concept. And it is the next component that creates the insect comparison.

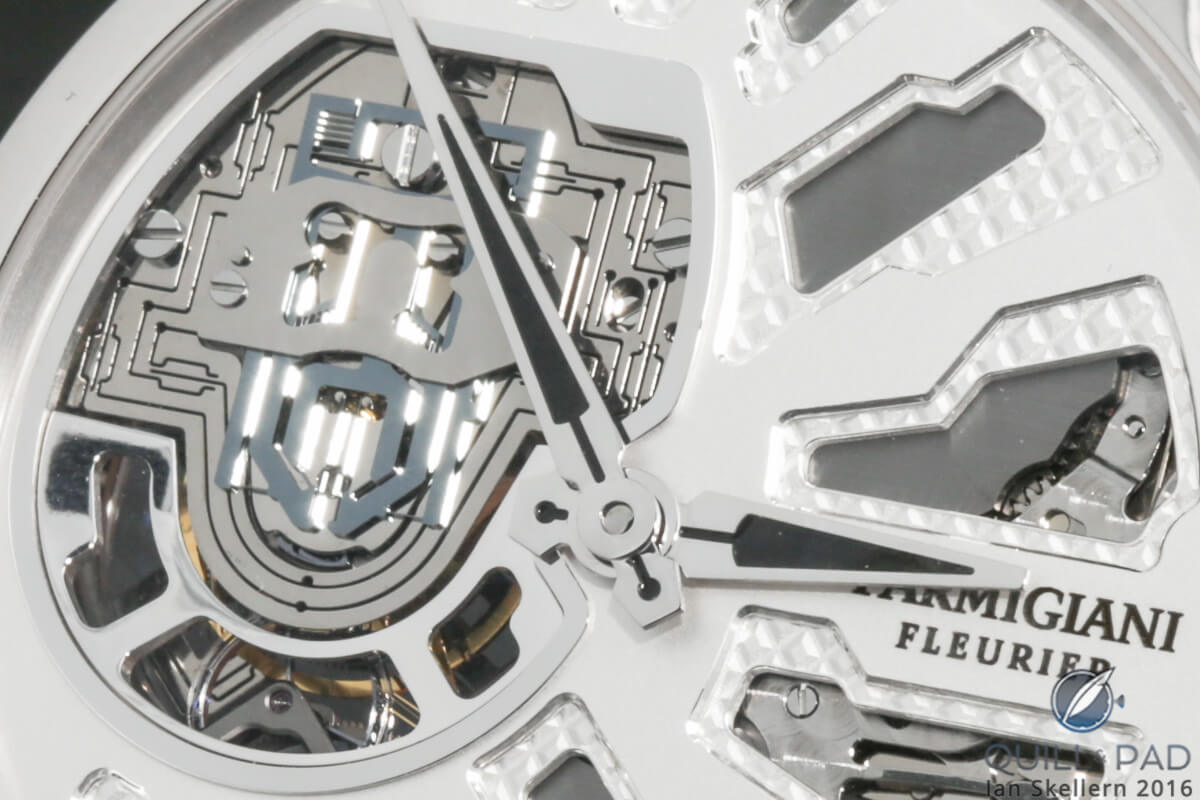

Close look at the intriguing circuit-board-like, ultra high-beat regulator of the Parmigiani Senfine concept watch

The oscillator assembly is connected via a shared almost-central mount with the pallet fork component also made of silicon. This component actually does not resemble a grasshopper even though it creates an action that is reminiscent of the insect’s movement. If it had to find a better shape comparison, it kind of resembles a whip spider, which is pretty cool if you ask me.

Back to how it works.

The oscillator assembly is mounted to the pallet fork component creating a virtual pivot shared by the pallet fork. This means the pallet fork also oscillates back and forth, something that should seem pretty familiar to any WIS out there.

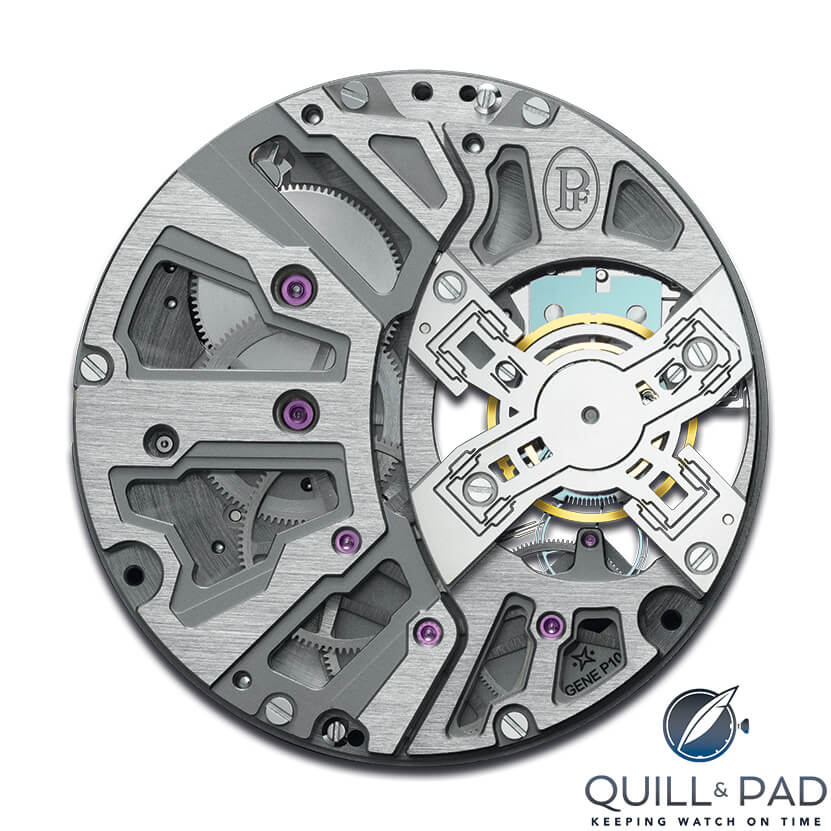

The extent of the oscillation of the pallet fork is limited in two ways. First, right above the pallet fork in the overall assembly is a silicon hairspring-like part that physically limits the oscillation thanks to its two long, thin blades and two pins that extend out of the pallet fork. This part is the isochronism compensator.

These pins press on the springs with each oscillation, receiving a push back to center just like a spiral wound hairspring but much more efficient and compact. This part also has the ability to be moved closer and farther from the virtual pivot, thus shortening or lengthening the spring arms and changing the beat rate of the oscillator. This way, precise adjustments can be made to the very high 16 Hz frequency.

The second way the oscillation is limited by the pallet fork is in its mating with the escape wheel. Just like other pallets, and similarly to the grasshopper escapement, the pallet fork has two arms that alternatingly lock on the escape wheel teeth.

Unlike most escapements, though, and just like the grasshopper escapement, the arms are never fully out of contact with the wheel. While one is moving in to grab the next tooth, the other is flexed in contact and reducing its flex to allow the escape wheel to rotate slightly to lock with the other arm.

Friction is the enemy

This is where the entire system starts to get extra nerdy. The fact that the pallet arms are always in contact with the escape wheel, plus the fact that the oscillator moves only 16 degrees of total amplitude, all with virtual pivots, ensures that friction and impulse forces are brought to nearly zero.

Since there are neither pivot staff nor jewel bearings, all of the friction inherent to a balance assembly disappears. That is one of the major points of energy loss in an escapement system, and here it has been completely eliminated.

The next factors constituting contributing to loss of energy in an escapement system are the impulse forces and resulting friction from the balance striking the pallet fork each swing to unlock the escapement.

Since the two components are mounted together and share the same virtual pivot, the entire impulse force there is eliminated. The only impulse force left in relation is the isochronism compensator spring that limits the rotation to 16 degrees, though the force on the blades of that component is almost directly linear, which reduces any sliding friction to nearly nothing as well.

Silicon in its single crystal form (which is what we have here) almost perfectly transfers energy with extremely little energy dissipation due to hysteresis or loss of energy output due to varying force input.

This means that the silicon blades of the oscillator assembly, the pallet fork, and the isochronism compensator allow energy to flow through the system with almost perfect rates of transfer.

Combined with the propensity of silicon to never suffer from fatigue, the system should have billions or even trillions of operational cycles without breakage or wear.

The nearly perfect surface state of silicon when created using DRIE technology contributes majorly to the almost nonexistent friction. Each piece of silicon is contacting another piece of silicon and the perfectly smooth (down to the atomic level) surfaces don’t allow for anything other than atomic forces to contribute friction.

Well, in a perfect world anyway. The system still will have some friction and the surfaces are not completely perfect, simply nearly perfect.

That means friction still occurs and it needs to be calculated in to the design, but the amount is so small and generally unchanging due to the fact that silicon is so stable. The friction of the system won’t increase, at least where those components are concerned.

The mechanics of nearly perfect

As these components work together, they have such tight tolerances and are so finely constructed that the system is inherently sensitive to shocks. The slower the speed and the larger the components, the greater that risk.

Increasing the speed from the earliest 4 Hz prototypes up to the current version beating at 16 Hz (115,200 vph) helped a great deal with this, but certain design aspects needed to be addressed by modifying geometry and adding safety features.

The geometry was modified based on complex calculations and simulations, but the safety features were a bit more mechanically straightforward. First, the pallet fork arms that interact with the escape wheel have guards to limit the extents of flex in either direction. This provides a bit of assurance that the movement of the arms will be uniform and that should a shock occur they will not bend too far and snap. These components still are rather fragile due to how thin the silicon gets, but if kept in an acceptable range of motion they should function almost indefinitely.

Next, the arms and guards themselves are set between another set of guards, more like rims, that are added above and below the escape wheel to keep the arms from slipping off in either direction due to a vertical shock to the system. This maintains that the arms can move up and down due to shocks to a certain degree, but will always provide the proper locking and unlocking of the escape wheel.

Finally, the entire regulator system is mounted in a set of plates that resemble circuit boards but are far from them. These plates are made of steel and finely cut using a wire EDM process to create a plate with highly controllable flex characteristics. These plates also have the ability to be adjustable for alignment and regulation purposes.

Due to the very complicated shape of these plates, the regulator system has the ability to shift up to .05 mm in the virtual pivot of the oscillator assembly, providing a shock resistance similar in concept to the standard shock jewel systems, but much more controlled.

The addition of these safety features over the development of the system has increased the system’s resistance to shock by more than 100 times over the earlier prototypes. No figures were given as to what force this might equate to, but the engineers at CSEM were originally excited about shock resistance of 20 G, so we could guess that a shock resistance of 2000 G might be plausible. That is well within the 500 G to 5000 G range that watches can experience daily.

Results

So what exactly does all of this super cool tech get you? First, it creates a mechanism working more closely with material properties than any mechanical system in a watch. It enables super high precision rate control with extremely fast-beat rates, more than three times faster than the industry standard high-beat escapements of 5 Hz (36,000 vph).

It reduces friction and wear on the regulator system where friction plays the biggest role in timekeeping accuracy and power reserve. Thus, the rate is much more stable and the power reserve leaves the realm of measurements in hours or days and moves towards weeks and months.

In the current setup the power reserve with a single barrel is 45 days, and in the Senfine concept with double barrel it hovers around 70 days. That means you would only have to wind your watch about five times a year. That is comparable to very large clock mechanisms and is right on the cusp of achieving quarterly watch winding.

Add a micro rotor to the movement and the power reserve practically becomes a meaningless number since chances are you would wear the watch at least a few times a year and the nearly frictionless regulator would keep it going in the months in between.

I don’t really know how to express how excited I was to see this concept in a working timepiece. I had learned about the Genequand escapement a few years ago, but this finally brought it to reality for me.

I was so excited when first shown the system that I took over from one of the actual engineers attempting to describe the piece to me and started trying to describe it to him! Hilarity ensued, of course, but in the end I was left astounded, impressed, and very excited for the future of things to come from Parmigiani and the Senfine concept.

A big thank you to the folks from Parmigiani and CSEM who tolerated my childish glee and still took the time to explain the system and give me as many dirty details as they could. This was truly a highlight of my year so far, and we aren’t even done with the first quarter.

To learn more about the Senfine concept, please visit www.blog.parmigiani.ch/parmigiani-fleurier-unveils-senfine.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] as Joshua pointed out in his extra-nerdy article The Parmigiani Senfine Concept Features Grasshoppers And Silicon, when there is no pivot staff, the friction inherent to a balance assembly completely […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

You were right about the meaning of the word, but not that Esperanto is not defunct. More (or better research needed.

It looks like Decepticon sign.