by GaryG

Over the years that our Northern California collector group has been traveling to Switzerland for SIHH week, an enduring tradition has been the practice of “going into the countryside” during the second part of the week to visit with one or more independent watchmakers at their ateliers.

A display of new watches as seen during a visit at the De Bethune manufacture, January 2018

With the advent and subsequent expansion of independents’ participation at the Carré des Horlogers at the SIHH itself, this has become more difficult over the past few years. However, with the kind support of many of the independents, a willingness to travel more broadly within Switzerland, and the realization that not all great independent watchmaking is actually in “the countryside,” we’ve been able to sustain the practice.

This year, we had a bumper crop of meetings with independents; we started during our time in Geneva with Akrivia, and then ventured out to the Bernese Oberland for a visit with Beat Haldimann before circling back to the De Bethune manufacture and finally a visit to that shrine of watchmaking: the atelier of Philippe Dufour.

De Bethune Titan Hawk, photographed during our visit in January 2018

And that doesn’t even count the stop with our friends at Agenhor where I took delivery of the clock I purchased at Only Watch 2017 (see Why I Bought It: Carpe Diem “Only Watch” By Agenhor And HEAD Genève).

The same, yet different

While it’s still mind-blowing to me to have the privilege of visiting the workplaces of these talented artisans (and for that matter, the larger manufactures of the mainline brands), you might be excused for thinking that seeing four small watchmaking operations in the course of four consecutive days might ultimately become an exercise in mind-numbing sameness.

And of course, there are similarities; but at the same time the differences in philosophies, atmospheres, and operating models provide more than enough diversity to stimulate curiosity and make you marvel at the variety of ways there are of addressing a given craft.

The urban startup: Akrivia

If you find yourself in Geneva with a bit of time to spare, I strongly recommend that you make your way up to the Old Town and park yourself in front of the big window at Grand-Rue 15, the home of Akrivia.

What you’ll see inside is a beehive of activity with a set of youthful watchmakers working intently but also taking time to move around the room, greet friends, capture real-time videos for Instagram and Facebook at all hours of the day and night, and in general just having a wonderful time.

Visiting the Akrivia atelier, with Rexhep (at rear) and Xhevdet Rexhepi (foreground)

To me, the vibe at Akrivia definitely reminds me of my home turf in Silicon Valley – deadly serious in its ambition, but at the same time fueled by youthful exuberance. The operating model, in which each watch is made from start to finish by a single watchmaker, exemplifies the value placed on each team member’s skills and development.

Xhevdet Rexhepi demonstrates jewel sink beveling during our visit to Akrivia

The watches themselves reflect a mixture of reverence for tradition and sheer audacity with their profusions of sharp inner angles punctuating curved bevels and movement geometries based on an insistence on symmetry.

That’s not to say that Rexhep and Xhevdet Rexhepi and their team are overtly cocky, but I left Akrivia with a smile on my face and an even greater admiration than I’d had before for a set of young folks who are aiming very high indeed.

AK-06 by Akrivia

For more information, please visit www.akrivia.com.

The artisans: Haldimann

At Beat Haldimann’s small atelier located in a 1907 mansion in the Bernese town of Thun, everything is the same yet entirely different. Here, gorgeous time machines are made in an environment seemingly unconcerned with the passage of time; even the garden path on which the watchmakers can take a brief stroll is a figure-eight shaped “infinity loop.”

Visiting with Beat Haldimann in Thun, Switzerland

A hallmark of the Haldimann style is an insistence on the use of traditional methods; there are lathes and boring machines, but no CNC mills or other mechanisms unguided by the human hand. And the ultra-fine tourbillon cages are cut and shaped by hand with tiny saws and files, not stamped or spark eroded.

Tourbillon components for the H1 as seen at Beat Haldimann’s atelier

For the use of operations that are so deliberately traditional, Haldimann’s timepieces are in many ways quite radical.

There’s the H1 with its very large central tourbillon, whose escapement emits a distinctive “singing” sound; the H2 with its resonance mechanism based on a mechanical link between the balance spring studs of the two opposed tourbillons; the even more extreme H8, a central tourbillon that does not indicate the time; and the H9 with a blacked-out crystal that allows the moving parts of the watch only to be heard, not seen.

Workbench scene at Beat Haldimann’s workshop

The sense I got at the Haldimann atelier was of someone who seeks control in order to deliver excellence.

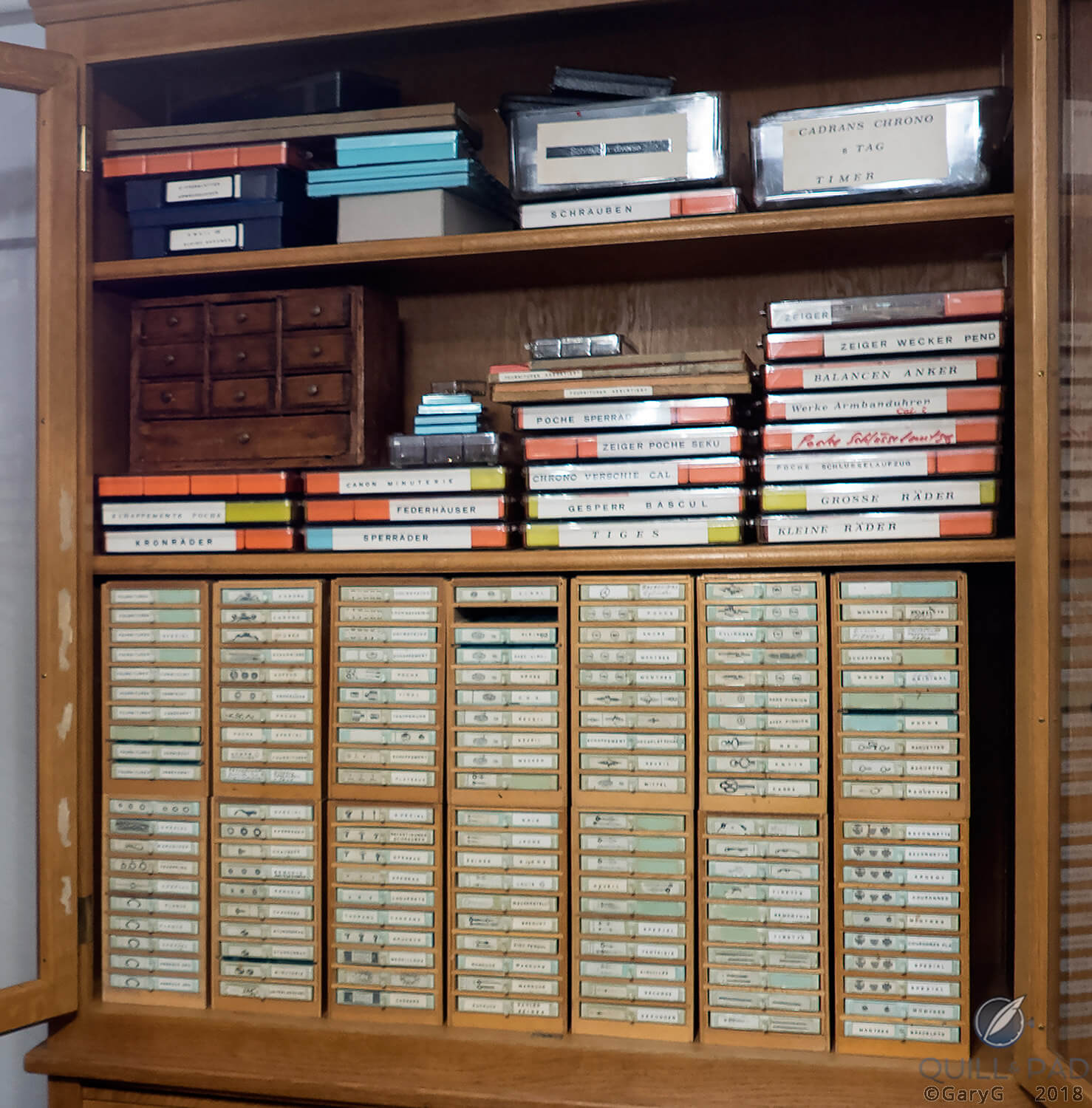

Haldimann bought the rights to prior watchmaking applications of the Haldimann name and along with them a stockpile of vintage and antique “Haldimann” watch parts, which are fastidiously cataloged and carefully stored on the lower floor of the mansion. With control of these resources in hand, he will service any Haldimann timepiece of any time period as well as his own timepieces, each of which consists of hundreds of hand-tuned parts that mesh in a way unique to that example.

Haldimann’s timepieces come with a lifetime warranty.

Spare parts for vintage watches made under the Haldimann name

For more, please visit www.haldimann.swiss.

The mad scientists: De Bethune

While Beat Haldimann files away at a tiny and intricately shaped piece of metal, De Bethune’s Denis Flageollet sits behind a large computer screen, shielded from prying eyes by a sloping ceiling beam, imagining the latest in a torrent of watch designs that mesh futuristic shapes with technical wizardry.

Materials magic: titanium components for the De Bethune Skybridge and Starry Sky

On a prior incarnation of the company’s website, De Bethune referred to itself as “Modern Day Alchemists.” And with innovations such as aerodynamically shaped balance mechanisms, a high-inertia titanium-platinum balance, meteorite cases, and liberal use of flame-blued titanium, the boutique brand more than lives up to the name.

A visit to De Bethune begins with the smell that is in many ways almost a cliché of watchmaking tours: the spray of machine oil in the room where computer-guided tools turn out the dizzying variety of parts needed to make the full range of De Bethune models.

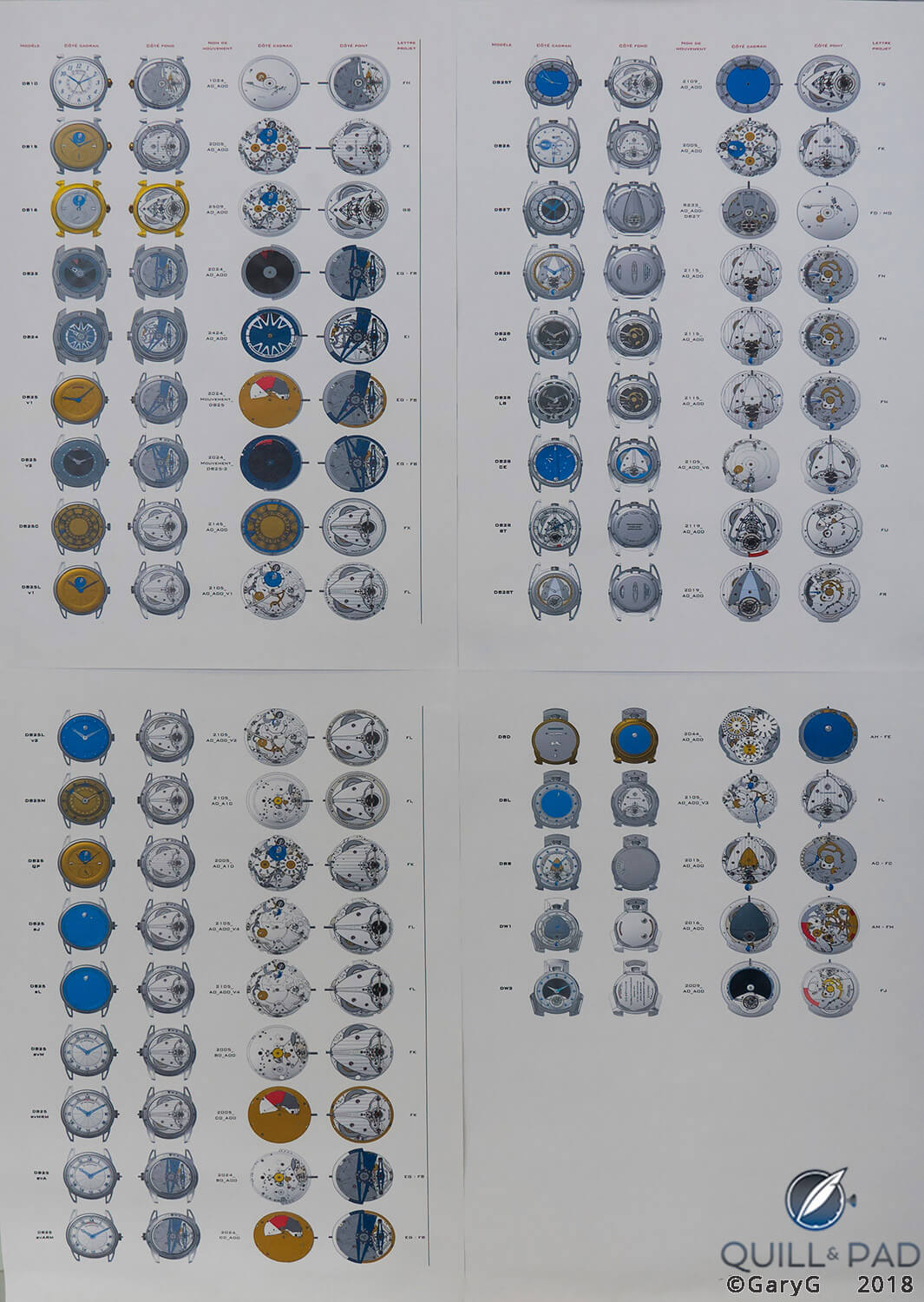

And throughout the tour, there are constant reminders of the two themes of material science wizardry and product-line proliferation, including the wall chart of De Bethune movements as seen below.

Display of in-house De Bethune movements

The demonstrations of skills like bluing, perlage, and the placement of white-gold beads and tiny diamonds into the drilled holes of the Starry Sky’s blued dial were carried out by a small number of craftspeople, each of whom played multiple roles. It wasn’t until I started puzzling about the distinctive wooden watch that seemed to be worn by several workers that I realized that the same person had been moving from floor to floor and station to station!

Don’t I know you? Setting gold beads in a Starry Sky dial at De Bethune

A cordial, yet very brief, meet-and-greet with Flageollet and his associate constructeur, who works with him on movement design, reinforced my overall sense of De Bethune, which had been building throughout our visit: an enterprise based on a cauldron of innovative technical and design ideas inside of Flageollet’s head that rushes for expression in a way that is almost overwhelming to the small, devoted team that brings them to reality in the metal.

This year’s new introductions suggest that perhaps the brand is re-finding a sweet spot where innovation meets customer appeal; I’m very hopeful that Flageollet and his team will be able to find a suitable balance between creation and discipline that allows them to not only survive but to thrive.

Man on the moon: the author’s reflection on a just-blued bimetallic moon sphere at De Bethune

For more information, please visit www.debethune.ch.

Guardian of history: Philippe Dufour

And then, of course, there was our visit with The Man Himself, Philippe Dufour.

To arrive at the small former schoolhouse in Le Sentier is to be in horological heaven, with the opportunity to see current projects in progress complemented, and if anything exceeded by, the stories told and history recounted by Dufour.

Philippe Dufour at his Le Sentier workshop

There’s no telling what will come out of the back corners of that massive safe when you visit; this time, in addition to some of Philippe’s own prototypes, we were shown other pieces like the one illustrated below: a steel-cased repeater that Dufour had built up from a rescued ebauche discarded at the local dump as part of a pile of “scrap” by one of the local watch companies.

Steel-cased minute repeater by Philippe Dufour based on a discarded movement

We were treated to a demonstration of burnishing, an explanation of hardening and tempering techniques that strengthen steel while avoiding brittleness, and the secret behind why Dufour favors curved bombé edges on the plates and bridges of his movements.

There were also stories of the lore of the Vallée de Joux, illustrated with vintage catalogs of movement drawings, and as a special treat a quick look at the Japanese comic book featuring the legendary watchmaker.

Philippe Dufour explains the prototype Duality differential to visitors

Of course, we got to see the famous vista of the top of Dufour’s workbench as well as his grandfather’s tool chest, which sits next to it. And on an adjacent bench, the practice movements being worked on by his stepdaughter, who now has ambitions of becoming a watchmaker herself.

Philippe Dufour’s workbench

It’s all about the people! Yes, there are watches involved, but ultimately a visit with Philippe Dufour is about his humanity and his reverence for the watchmaking traditions of the Vallée de Joux.

Prototype movement, Grande et Petite Sonnerie by Philippe Dufour

Four days, four worlds

As you can imagine, piling these sorts of experiences on top of the intensity of the new introductions as SIHH makes for quite a week!

I’m both exhilarated and a bit tired just thinking about these visits and all that we saw and learned – and I’ll be interested to hear in the comments section below about your own experiences visiting the ateliers of these or other independent watchmakers.

Parting shot: the author and MrsGaryG with Philippe Dufour (center)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

What a great group of people and accompanying stories you were blessed with touching into

Completely agree with you Daniel — it’s such a privilege for me to have the opportunity to meet these wonderful creators!

Best, Gary