by Martin Green

There is something about interviewing people like Stephen Forsey, co-founder of Greubel Forsey, that makes it a unique experience. Not only is he a watchmaker, he is also an entrepreneur with his finger on the pulse of the industry.

He doesn’t have to spend time sketching out a dubious marketing landscape in which his watches are the best you can get, as they are the best that you can get. Instead, he uses that time to explain the intricate details, nifty technical solutions, and superhuman finish of his watches.

A close look dial side of the Greubel Forsey Tourbillon 24 Secondes Edition Historique in red gold

You might expect that with his track record he would have an ego the size of the Mont Blanc, but as is often the case with skilled watchmakers Forsey is very down to earth and accessible. He does what he likes, and he just happens to be extremely good at it.

Sitting down with Forsey for lunch recently in Amsterdam was actually one of those moments in which I thought that my profession can’t really be called work.

Stephen Forsey

Q&P: Most watch brands have to make “commercial concessions” to their work, while Greubel Forsey seems to be able to do what it likes. Is that really so – and if so, what made this possible?

SF: We are not marketing driven, so we also don’t start off with a marketing brief when developing a new watch. These are really born from a creative aspect. Robert [Greubel] and myself just sit down with our team, so I guess that the ideas that come up are quite different.

Robert is also a watchmaker so when he thinks about the creative side, which he oversees, there is already an aspect of the technique, and then I am working with the technical team on feasibility . . . can we get these displays there, yes or no?

Maybe we come up with some other ideas. It is a very involved process. If we wanted to be rational, we would have built like three calibers in our first 15 years, and with those three calibers we would have made as many different aesthetic variations, but we wouldn’t have brought much to the party for us if we stuck to that.

Greubel Forsey Différentiel d’Égalité

Q&P: On the grapevine, I’ve heard stories that Richemont has recently increased its stake in Greubel Forsey. Is this true and how much is the stake now?

SF: Nobody told me! (laughs) Well, we have “been for sale” since we started, and we have had the partnership with Richemont, who owns 20 percent, since 2006. In a logical, business way people like to put you in a box, so the initial reaction was that they assumed that we would sell out in two years, five years, or whatever. It is now 12 years later, and we still have the same structure. We have a very good relationship with Richemont, but for Robert and myself it is important to maintain that freedom of creativity that is very essential to us.

Q&P: With Richemont’s involvement, do you still consider Greubel Forsey an independent?

SF: Richemont is part of Greubel Forsey; it is not that Greubel Forsey is part of Richemont. We have control: we have 80 percent control of Greubel Forsey and 100 percent control of CompliTime. So this is an important thing to maintain the structure and the freedom.

The advantage of being independent is that you can have the freedom and liberty of creating something different. The difficulty is that this also usually means that your projects are very costly to develop. We make such a small number of watches a year that our research-and-development expenditure is very, very high.

Stephen Forsey and Robert Greubel with the proof-of-concept Meccano of their Double Tourbillon 30° regulator

Q&P: You have worked for Asprey and Renaud & Papi and co-founded CompliTime before you started with Greubel Forsey: what is a personal accomplishment that you are most proud of?

SF: Definitely our team at Greubel Forsey in the atelier. We have a great team of people, passionate, professional, many different domains and quite a young team as well. It is something that we also like to put in concrete with our Time Æon Foundation. We founded the Time Æon Foundation in 2008 to draw attention and try and bring more of a profile to a loss of fundamental and more traditional watchmaking skills.

It’s difficult to get support for that, and it is not easy to understand why the industry doesn’t really want to come on board and participate more actively, but that’s what it is. It doesn’t stop us from continuing. We have in our [Greubel Forsey] team quite often young people, surprisingly young, who need to build experience, which takes, of course, a lot of time, energy, and resources. If they have the passion and the motivation, and enough of a grounding, then we can build something together. This is something that is great to see, and it enables us to make fresh creations, keep our innovation and inventions dynamic, interesting, and engaging for the watch community.

Slowly we build in our own microscopic way because with 115 people Greubel Forsey is a tiny, tiny drop in the ocean of the watch world, but in our own way we make a difference. I think it is important to do something, even if it is in a relatively modest way.

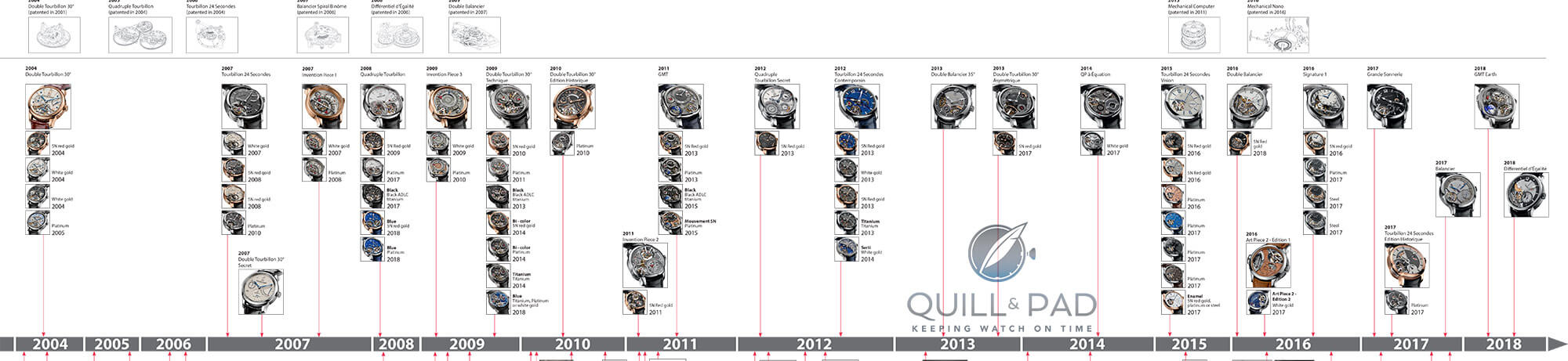

Timeline of Greubel Forsey inventions and timepieces

When you look at the lineup of the calibers that we built in the last, almost 15 years now, it is a lasting testimony. Robert and I started out in 1999, and very few people were talking about hand-finishing. It was more an extraterrestrial thing with Philippe Dufour out there, and that was more or less it. It is something that has gained more interest, and the more and more educated the collectors become, the more we see interest and people actually coming back to us.

We maintain the past, which is different, because we don’t have the objective to be a mainstream brand, to build large volumes. It is not where our focus is. It is always difficult, I feel, for people to categorize Greubel Forsey because we don’t fit in a box with another brand.

Q&P: Greubel Forsey is in a category of its own?

SF: In a way, without being egotistical about it, yeah. We set out with an idea of creating a watch that Robert and myself, as watchmakers, would find interesting and engaging. One that is technically innovative with an original approach in terms of creation, three-dimensional mechanical architecture to the movement, more than just a standard watch movement, and then the finish and performance. It is quite a tall order, when you put it down on paper, to try and do that, but these are our driving forces, this is where our energy and motivation comes from.

Q&P: Is this also what guides the development of new watches, both technically and aesthetically?

SF: Yes. If we wanted to be more commercial, we would have never built 22 different calibers. The interest for us is very different. We realized that after the electronic watch crisis that almost all the research and development for mechanical watches stopped for a period of time, and then you saw it come back. There was a lot of knowledge, a lot of know-how and expertise, that was lost.

When we started CompliTime in 1999, one of the first things we did was start a laboratory. So we had a watchmaker who was a laboratory technician so that we could study and start to rebuild our know-how and expertise about mechanical movements and all the different phases.

So for us, the prolific creation of calibers at Greubel Forsey being completely disproportional to the number of watches we build is very important. Each of them enables us to build our know-how and experience. It adds a small element, it answers a question each time – or maybe we hope to answer a question, but we actually get a bunch of more questions. That is research, and it doesn’t always bring an absolute answer.

For example, we were recently talking with a client about our 4th Invention [Balancier Spiral Binôme], and he asked what is going on with this balance and spring binôme idea . . . [and I had to explain that] it is a process, not just a platform or a marketing tool to announce in advance what is coming up. It really is a research approach that raised a number of difficulties because when we built a balance and spring in synthesized diamond, we realized that the technology wasn’t really up to the level we needed for watchmaking. It did bring us an experience and helped us to identify more on the subject of mechanical nano. One specific question has brought us a whole new domain and area to explore.

Greubel Forsey Grande Sonnerie on the wrist of Stephen Forsey

Q&P: Does that also go for the Grande Sonnerie that you made? You worked eleven years on that . . . can you ever make such a thing commercially viable?

SF: It is a project that is of course very difficult for us on all fronts, but it would have been hard to build a traditionally based Grande Sonnerie, which is a fantastic achievement in itself. In the twenty-first century, if we were going to build a grande sonnerie or a striking watch, we wanted to build one that is really in focus and pertinent for this century.

For example, water resistance: it is easily written down as a line on the specifications, but it is super difficult to have water resistance for a striking wristwatch and maintain a good level of intensity of sound and a good quality of acoustics for the sound. This is just one example. When we were doing that, we, fortunately, had very good experience with antique watches and more modern striking and repeating watches and their development, so we made a whole particular study of acoustics, with the gongs to create this resonating chamber with the case body itself to get the sound out through the metal rather than to just rely on air transmission.

Because there are two ways to transmit sound: through the air, but when you create a water-resistant watch you reach a stumbling block, or through the material so you have to make the whole case resonate. This is just one particular area, and to add to that the securities of the function, as we have already been able to have in our perpetual calendar, this for the Grande Sonnerie was a must. So we could give it to anybody, and they can’t break it. That is quite a tall order: a one-liner on the specifications, but it implicates a huge body of additional work to do that.

So it was eleven years of challenges. It would have been good to complete it earlier, of course, but we also wanted to make sure that it would work well, so Robert, because he doesn’t travel so much, was able to wear it for three years when we did the final testing and finetuning with some details. We made a number of improvements through that. The result is that when we launched it last year, in 2017, we delivered five pieces and this year we will be able to build eight, and we are already halfway there.

That’s the maximum, it is a huge amount of work. It almost represents two years of working hours to make, bring together, hand finish, assemble, and finetune the 935 components of the movement in the Grande Sonnerie. You also cannot do that with just any watchmaker. Also in terms of acoustics, the biggest challenge is that you cannot simulate everything, so it is only when the piece is almost completely finished that you can really be sure if it works or not.

Greubel Forsey Quadruple Tourbillon in red gold with blue dial

Q&P: Greubel Forsey also offers the option for a completely bespoke watch: how does such a process work?

SF: It is possible within our collection to do personalization. There are collectors who, when we start to get to know them better, ask for such-and-such a case material, or maybe they’d like a special dial, things like that. When they have an idea for a watch they approach us, then Robert and I make some proposals with our team.

Usually, we have about two or three proposals and then they can choose the one they like. It is quite a one-on-one approach, rather than having a presentation catalogue out of which a client can choose different options. It is not a predetermined bespoke approach. We try to work within a framework, but because we make such small numbers a client can just have a special dial.

To make a one-off dial is hugely expensive, especially with the complexity of our Greubel Forsey dials, which are multilevel in gold; it can easily be 20 to 30 parts that make up the dial. It is much more than a traditional watch dial. But there are limits, and sometimes we do say no if it really doesn’t fit our philosophy.

Q&P: What wouldn’t you make?

SF: (Laughs) I don’t want to put that out there because then somebody will request it!

Q&P: What is your ultimate goal with Greubel Forsey?

SF: It is to maintain this traditional watchmaking. We have done this with our hand-finishing since day one, and today in our collection we have on average about four months’ worth of man-hours of finishing, so it is quite a significant amount in relation to the total time to build the watch. This is an important legacy, and it is interesting to see that collectors appreciate more and more hand-finishing.

And as the knowledge gets transmitted, certainly today the level of expectations is generally higher than what it would have been a few years ago. Those are all positive things. What is our aim? To make a small difference if we can. To share our passion for fine watchmaking, to inform, to bring that to a younger generation, to get them on board and join the adventure.

For us, mechanical watchmaking brings something to a general level of culture, which is a very unique domain, so it is up to us to defend that and share that passion and get people to get on board.

Q&P: Is this what gets you up in the morning?

SF: Yes, definitely! We are guardians of a certain heritage. We have 500 years of mechanical watchmaking behind us, and for 450 years during that time, the mission was to create an absolutely precise mechanical mechanism to measure time absolutely precisely.

This is still one of our main missions also, but we have realized that there are these other areas in terms of hand-finishing, there are things that we had hoped we could achieve like the Quantième Perpétuel á Équation, to bring a single correction, bi-directional correction of all the calendar functions simply from the winding crown. This was something Robert and I thought about many years ago, and it is great to bring these new mechanisms to life.

Invention Piece 1 by Greubel Forsey

Q&P: What is your personal favorite watch from the Greubel Forsey collection? I know that this is almost like asking a father which is his favorite child . . .

SF: Exactly, that is usually my response. The other response usually is, “The next one.” Honestly, I think one of the really, really important pieces, the complications like the Quantième Perpétuel á Équation and the Grande Sonnerie, each one is very unique in its own way and brings something new. But our first piece, the Double Tourbillon Vision was a landmark piece because at that time we didn’t have that structure yet.

That set the bar, then you’ve got to stick to those codes and that mission. But over and above all those pieces, the Invention Piece 1 is perhaps the one that really stands out, because that was the piece where collectors came back to us and said, this is more than just another mechanical watch.

We really have brought something together that was a game-changer in its own way, because of the three-dimensional architecture of the movement, which was really defining, the hand-finishing, putting the mechanism at center stage, and putting the time display in a different position. Bringing all these things together was a very unique moment and it was unconscious, it wasn’t deliberate to make a defining sort of split, but I think that it really underscored the difference between our mission with Greubel Forsey and the stereotype vision of a watch company.

We are not in the mainstream.

For more information, please visit www.greubelforsey.com.

You may also enjoy:

Greubel Forsey Grande Sonnerie: Confounding Expectations In A Class Of Its Own

Does Hand Finishing Matter? A Collector’s View Of Movement Decoration

Why I Bought It: Greubel Forsey Invention Piece 1

Mechanical Computers From Then To Now: Greubel Forsey Quantième Perpétuel á Équation

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

What’s it feel like talking to a guy who normally wouldn’t give you the time of day except he knows you’re going to promote his product to the millionaire & billionaire class? Do you feel used?

Wow, Mike, you obviously have never met Stephen Forsey, so I’m wondering if that ignorant comment comes from insecurity, jealousy, or were you just having a bad day? Or all three? You might find that things brighten up for you if you can knock that large chip from your shoulder. I wish you luck.

Regards, Ian

As a young watchmaking student in Great Britain, I attended the British Horological Institute’s 150th anniversary. Stephen Forsey was one of the keynote speakers and he seemed like a lovely man. The majority of the audience were humble watchmakers’ students and those with an interest in horology. I can assure you the billionaire class was nowhere to be seen. Odd advertising move in my book. Perhaps he just really wanted to attend an important horological event and to share some of his passion with others that had an interest. I feel like this comment should get the “ignorant of the year” award.

Mike, Stephen has given me the time of day when I was a nobody in this industry and didn’t have a publication to write for. I hope that one day you will meet him and have the same experience, as I know you will do a 180 on your opinion.