For 175 years, Glashütte has been associated with some of the finest horological masterpieces in the history of watchmaking. Here in Germany’s picturesque Müglitz valley, some of the noblest elements of fine watchmaking were invented, including the flying tourbillon, the duplex swan-neck fine adjustment, and the three-quarter plate. Distinctive hand-finishing techniques, movement decorations, and technology set these Germanic masterpieces apart from the venerable art of Swiss watchmaking.

A. Lange & Söhne finishing techniques

From the beginning, the fascination of Glashütte’s fine timepieces has been motivated by both the precision and exact proportions lending the noble timepieces their harmonious and elegant appearance, including the numerals, markers, hands, indications, case, bezel, and strap as well as the sophisticated mechanical microcosm inside each timepiece.

Movement design discussion at A. Lange & Söhne

Behind the sapphire crystal case back, where myriad tiny components interact with each other in perfect harmony, the outer perfection mirrors the inner values. A glance through the pane reveals finest mechanical beauty as deep as the eye can see. The knowledge that each of these parts, some of them barely visible, reliably fulfill their functions every second for years and decades to come brings pleasure to enthusiasts, collectors, and even the casual observer.

Every single component, no matter how small, is lavishly finished to perfection. The composition of aesthetic details ranges from various decorative cuts to polishing, chamfering, beveling, and artistic decorations such as skeletonizing and engraving.

Two Glashütte-born inventive flyback chronographs based on the same plans: Urofa Caliber 59 from 1940s (left) and the new Tutima Caliber T659

Just as in the early days of Glashütte’s history, contemporary experts and artisans remain dedicated to these specialized forms of craftsmanship. And with modern manufacturing processes, skilled Glashütte craftspeople execute the lion’s share of their work by hand. The result is a complete work of art justifying the time-consuming effort.

Here I have put together highlights of the most traditional technical and aesthetic signature elements of “made in Glashütte” contributing to its world-renowned horology.

7 technical hallmarks of Glashütte’s fine watchmaking traditions

Three-quarter plate

Perhaps the most famous and recognizable element in Saxon watchmaking is the three-quarter plate, which practically serves as a synonym for the Glashütte art of watchmaking. Generally made of German silver and designed to improve the stability of the movement, the three-quarter plate was invented by Ferdinand Adolph Lange, founder of both A. Lange & Söhne and the entire Glashütte watch industry.

As its name implies, the plate covers three quarters of the movement’s surface, providing a stable home to all the movable parts from the spring barrel to the escape wheel.

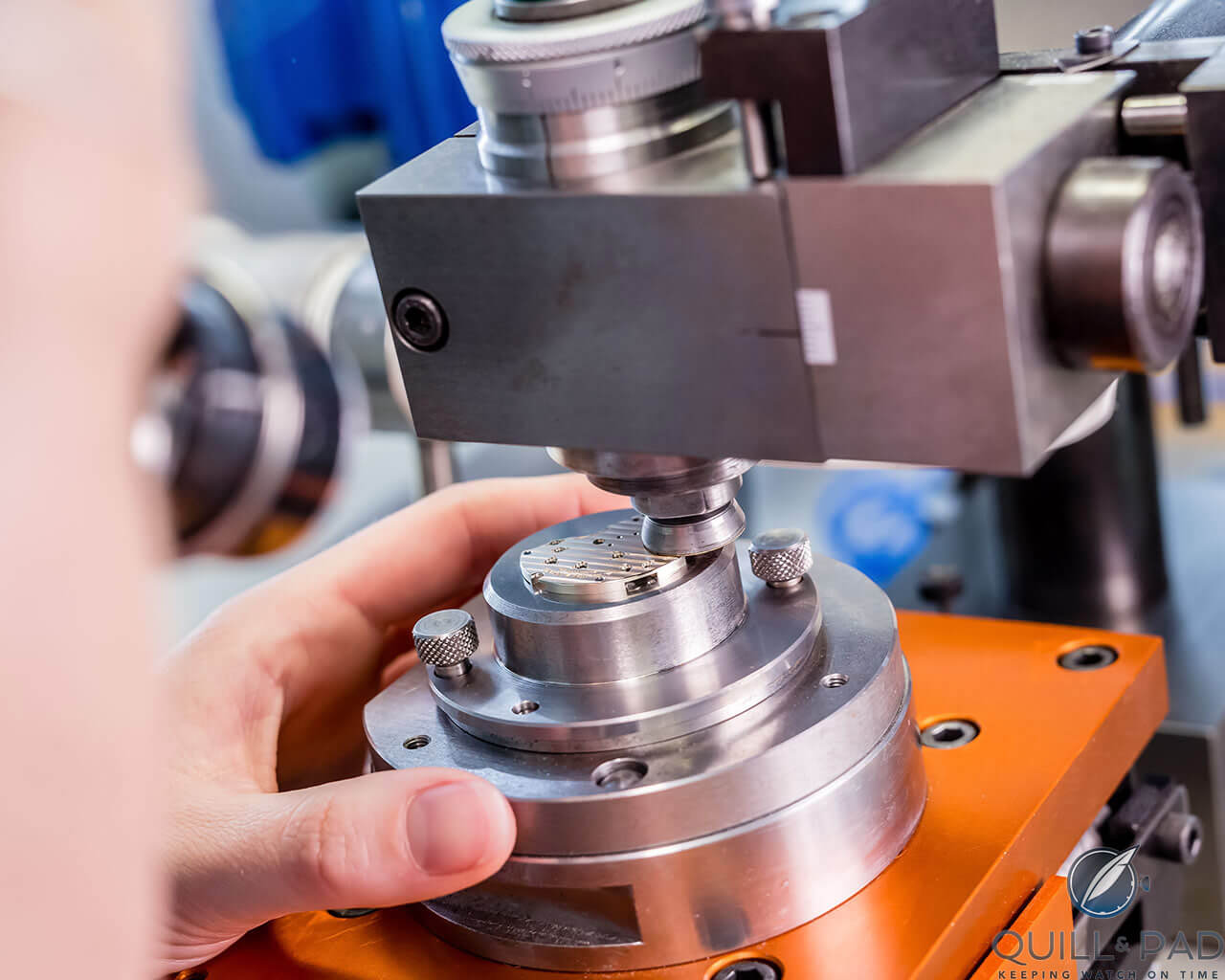

Applying Glashütte ribbing to a three-quarter plate at A. Lange & Söhne

In addition to facilitating maintenance, this design aided in minimizing dust in pocket watch movements. Traditionally, the surface of a three-quarter plate is finished with Glashütte ribbing, a polishing technique emulating a gentle rippling effect like Geneva waves (côtes de Genève), the Swiss counterpart. The difference between the two is the angle at which the undulating pattern is applied.

Joshua Munchow wrote a poem in honor of the three-quarter plate, which you can read in Ode To Three-Quarter Plate Movements: A Poem.

The prominent German silver three-quarter plate of A. Lange & Söhne’s Pour le Mérite Tourbillon

Swan-neck fine adjustment

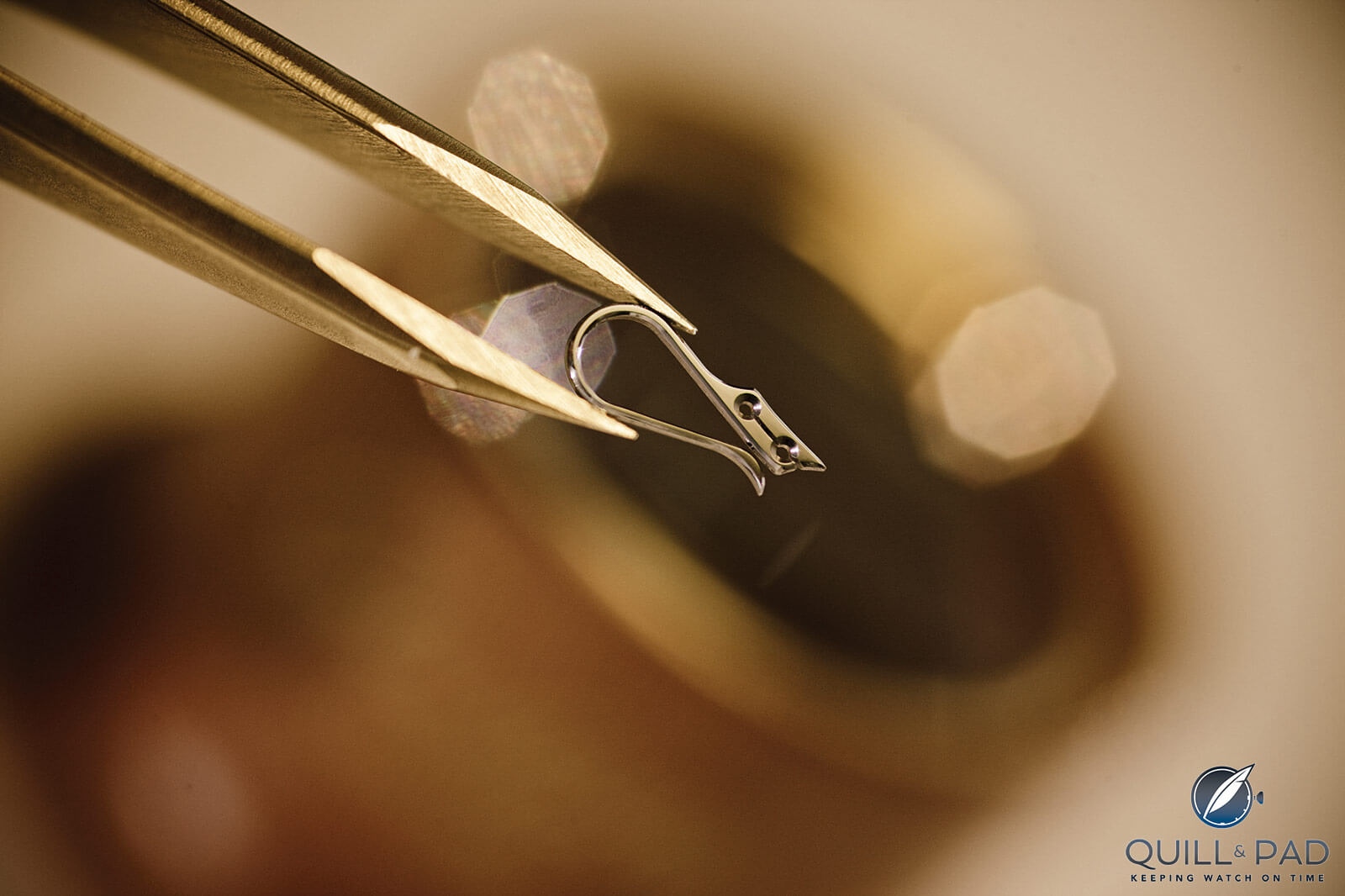

The swan-neck fine adjustment also goes back to the early days of Glashütte, and it catches the eye thanks to its distinctive shape resembling a swan’s neck. The fine adjustment mechanism comprising an index and a curved stainless-steel spring is screw-mounted onto the balance cock.

A swan-neck fine adjustment with elaborately engraved balance cock and blued screw by Glashütte Original

Pushing the spring against the index allows for fine corrections of the rate/timing. By turning a screw set into the side of the spring, the index can be moved to achieve the desired rate. The spring creates the necessary return torque to precisely adjust and hold the index in position.

Tin polishing at Glashütte Original

Its miniscule size and precision require meticulous fabrication: Glashütte Original’s swan-neck spring, for example, is only 7.8 mm long, 3.4 mm wide, and 0.54 mm high. Despite the small dimension, it is mirror polished using a manual process called tin polishing.

Tin-polished swan-neck spring by Glashütte Original

Glashütte Original has taken this component a step further too, introducing a modern (and beautiful) duplex swan-neck spring.

The beautifully engraved balance bridge and mirror-polished duplex swan-neck regulator of the Glashütte Original PanoMaticInverse

Screw balance

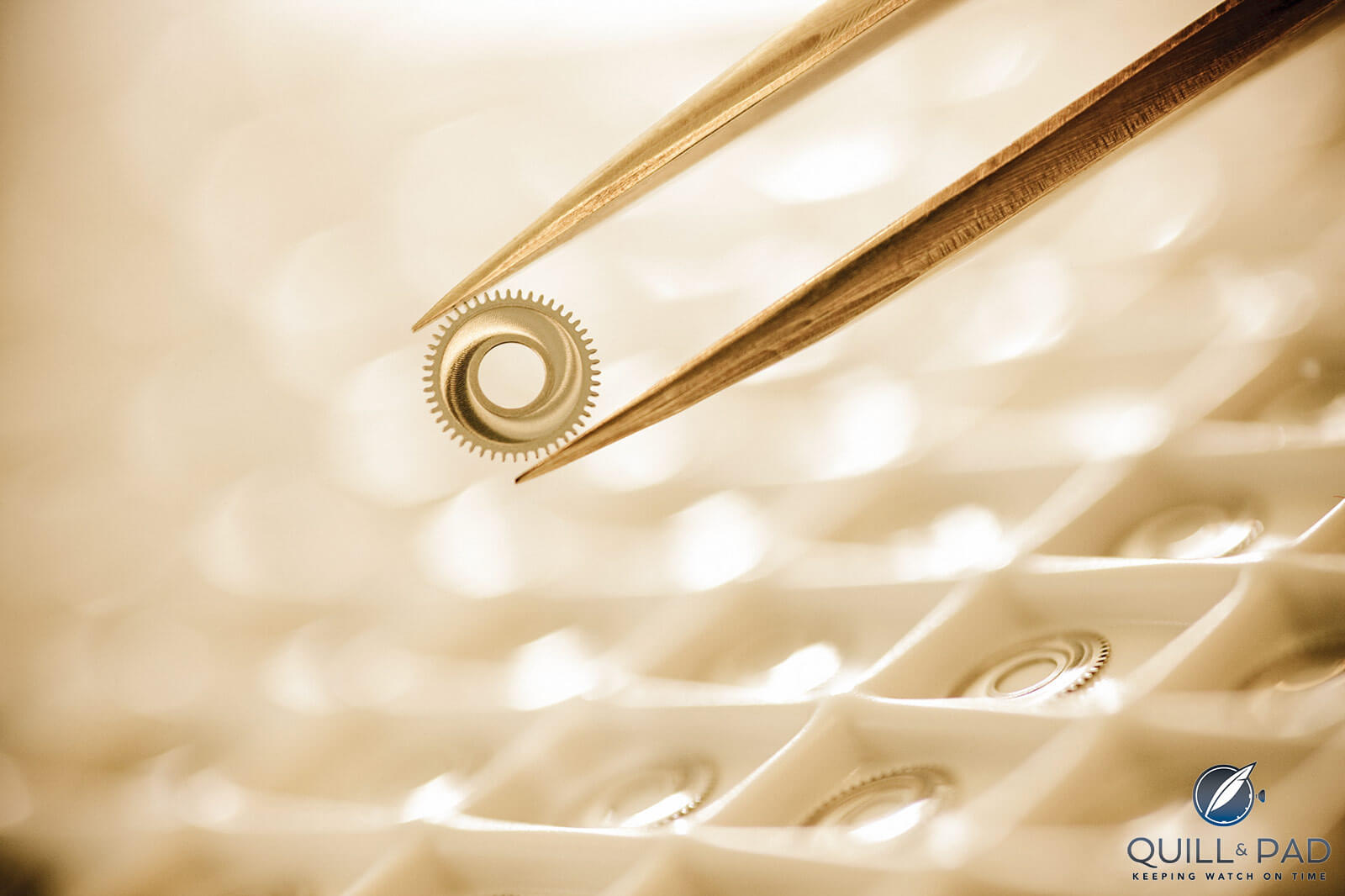

The screw balance wheel is a traditional variation featuring 16 to 18 tiny screws around the periphery of the balance wheel. Their purpose is to correct imbalance and add inertia. This minute yet sturdy design lies at the heart of the movement’s precision.

Assembling the screw balance at Glashütte Original

Glashütte stopwork (Glashütter Gesperr)

The Glashütte stopwork is a type of ratchet spring that allows the mainspring barrel to reverse slightly after winding to prevent overwinding. Slightly different from Swiss-made winding mechanisms, the spring pairing with the ratchet wheel is longer and more prominently curved.

Both sides of the Tutima Hommage Minute Repeater’s movement with Glashütte stopwork prominently visible at 4 o’clock on the left image

Flying tourbillon

The flying tourbillon is a sophisticated haute-horlogerie take on the classic tourbillon that is supported on just one side. Forgoing a top bridge, the open construction revolves around its axis in one minute, highlighting the animated tourbillon while offering an uninterrupted view. The flying tourbillon was invented by Alfred Helwig 100 years ago.

Inserting the flying tourbillon into the movement of the Glashütte Original Alfred Helwig Tourbillon 1920 – Limited Edition

The virtuoso design certainly inspired some of the most daring tourbillons of today and can also be found in Swiss masterpieces. However, it is Glashütte Original who in 1995 first transferred the flying tourbillon into a wristwatch and has since then introduced several sophisticated limited examples that are highly sought after by collectors.

Auf und Ab (Up and Down) power reserve indicator

The “Auf und Ab” is a power reserve display dating back to the heyday of Glashütte’s precision pocket watches.

A. Lange & Söhne’s Zeitwerk Decimal Strike with prominent Auf und Ab power reserve indication

A distinguishing signature of Ferdinand Adolph Lange’s legendary pocket watches, today an “Auf und Ab” display is the common design for a Glashütte-born power reserve indicator.

Gold chatons

Screw-mounted gold chatons are another hallmark of top-notch Glashütte watchmaking. Here, the jeweled pivot bearings are set into a bed of gold placed into bridges and secured by three blued screws.

Adding gold chatons to the three-quarter plate of a Lambda model at Nomos Glashütte

Each chaton is fitted precisely into position so that it neither juts out nor comes loose. From an aesthetic point of view, the color composition combining the ruby red jewel, cornflower blue screw, and warm gold chaton creates a magnificent visual.

Fine finishing details and prominent gold chaton on the balance cock of Caliber L141.1 powering the A. Lange & Söhne Lange 1 Time Zone

5 aesthetic hallmarks of Glashütte’s fine watchmaking traditions

Hand-engraved balance cock

The engraved balance cock is a purely aesthetic feature. Tiny floral ornaments are engraved into the surface of the one-armed bridge supporting the balance wheel and hairspring. The filigreed engravings executed by experts’ hands make every decorated cock unique. The depth of the cuts and shape of the curls of the lines are like inimitable fingerprints – a personal signature setting each one apart from the others, even when they have superficially similar patterns.

Hand-engraved balance cock with diamond endstone in A. Lange & Söhne’s Pour le Mérite Tourbillon

Blued screws

During final assembly, the first-pass fixture screws are often replaced by flawless, thermally blued screws. Their characteristic cornflower blue hue is achieved by slowly and very carefully evenly heating the steel screws to just the right temperature. The bold color contrasts against the German silver three-quarter plate to effortlessly catch the eye.

Bluing screws at Glashütte Original

Sunburst decoration

Sunburst decoration is special polishing technique dating back to 1868. It is usually applied to round and flat components that rotate and is most often found on the ratchet wheel. Depending on the visual angle, the light is reflected like a sunburst. Single, double, and triple sunburst techniques all exist.

Sunburst decoration on winding wheels at Glashütte Original

Chamfering and beveling

While the traditional finishing technique of beveling is not exclusive to Saxon watchmaking, at the Glashütte manufactories all edges of metal surfaces are painstakingly beveled to an angle of 45 degrees.

Assertive, clean beveling on the A. Lange & Söhne Lange Double Split movement

This process creates shiny and decorative edges, but also a higher resistance by densifying the surface. The same result is created by chamfering, the difference being that a bevel runs across the full thickness of the plate while a chamfer cuts across a 90-degree angle.

Beveled edge (top) versus a chamfered edge (image courtesy Wikimedia)

Find out much more about beveling in Does Hand Finishing Matter? A Collector’s View Of Movement Decoration and Why We Are In A Golden Age For Appreciating Superlative Hand-Finishing In Wristwatches.

Perlage

Like beveling, perlage is widely common in high-end Swiss movements as well as German calibers. It consists of overlapping, pearl-shaped circles created by a rotating rubber peg covered with a special diamond powder that is hand-applied to the surface. Connoisseurs can easily spot perlage on the insides of wheel plates or the dial side of the movement’s base plate. Also known as circular graining, perlage is thought to have had the original function of “catching” dust before it progressed further into the movement.

Applying perlage to a movement component at A. Lange & Söhne

You may also enjoy:

175 Years Of Watchmaking In Glashütte: A History Of Fine German Watchmaking

Nomos Glashütte Lambda In Stainless Steel: Celebrating 175 Years Of Fine Watchmaking In Glashütte

90 Years Of Tutima: An Abbreviated, Complete History

Made In Germany: The Glory Of Glashütte

‘Made In Glashütte’ Vs. ‘Made In Germany’: What Puts Them Together, What Sets Them Apart

Q: Who Was Alfred Helwig? A: Inventor Of The Flying Tourbillon

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Nice! Due to pick up a Lange Saxonia Thin next week and that L941.1 pic at the top looks very like the L093.1, so I can pore over it to look at the similar finishing.

Which Saxonia thin are you getting, Gav? I am still seriously drooling over one that came out two years ago and is due an upgrade very soon….

The 37mm rose gold 201.033. Is that the one due an upgrade? *holds breath*

No, it’s not the one I meant.

Phew! I think I know the one you mean, though.