Watch- and clockmaking has a long history in Germany, as evidenced by the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century timepieces from the Nuremberg/Augsburg area and the academic discussions of Peter Henlein, who is said to have made the world’s first pocket watch around 1505.

Watches and clocks were also made in the Black Forest region from the seventeenth century as well as the nearby “gold city” Pforzheim starting about 100 years later, which was (and remains) renowned for jewelry as well.

A memorial statue to Peter Henlein was built in his hometown Nürnberg in 1904 (photo courtesy Aarp65/Wikipedia Commons)

Germany’s comprehensive history in clock- and watchmaking is fascinating, but here I focus on the history of a small Saxon called Glashütte as it celebrates its 175-year anniversary in 2020. Glashütte is the most famous German center for high-end watchmaking today. Its unique history and literal rise from several sets of ashes qualify it as one of the most persistent phoenixes in watchmaking circles.

Glashütte early history

Glashütte (pronounced gläs-hyu-teh) is located in the German state of Saxony, about 30 kilometers from state’s capital city Dresden to its north and about the same distance from Czech border to the east. The town is nestled in the valley gorged from the Erzgebirge (German for “iron ore mountain range”) by the Müglitz river.

The village of Glashütte was founded in the year 1450, and its establishment had a lot to do with mining in the Erzgebirge mountain range surrounding it. Silver was discovered here, and this is how Glashütte (German for “glass hut” or “shiny hut”) received its name. In 1506 the village officially became a city.

A modern view of Glashütte

Silver was mined in the region for only a few decades, after which the small, yet prospering town fell upon hard times. The 90 Years War, the Northern War, and the Seven Years War did incredible damage to the area for about a century. The price of silver decreased due to discoveries in the New World, and by 1780 only 500 people were living in Glashütte.

In 1791 Glashütte suffered a catastrophic fire that burned about half of the town’s houses. The war of 1806, which lasted until 1813, brought yet a new round of suffering, and people fled to Dresden and flatter ground.

In the nineteenth century, Saxony proved an industrially strong region within a not-yet united Germany. A sovereign state, Saxony was at the forefront of many industries at the time, and its first railroad – which ran between Dresden and Berlin – commenced in 1839.

But the eastern Erzgebirge region was not included in the upswing as it was too isolated. In 1831, Glashütte’s city council sent its first request to the Saxon government for aid. The government took years to react (some things never change!), and when it did, it put out public notices to search for tradespeople to create industry in “emergency” areas.

If this had been a movie script, I imagine Ferdinand Adolph Lange would have played the deus ex machina at this point, swooping down to save the failing city. But the situation was real life, not a Hollywood film, even if its telling makes for a good story today.

Ferdinand Adolph Lange and the step-by-step establishment of a watch industry

F.A. Lange – who went by “Adolph” – ended up playing the part of knight in shining armor, answering the government’s call with a far-reaching, far-seeing concept designed to not only aid the declining region but to establish an entire, completely new, organized watchmaking industry one step at a time.

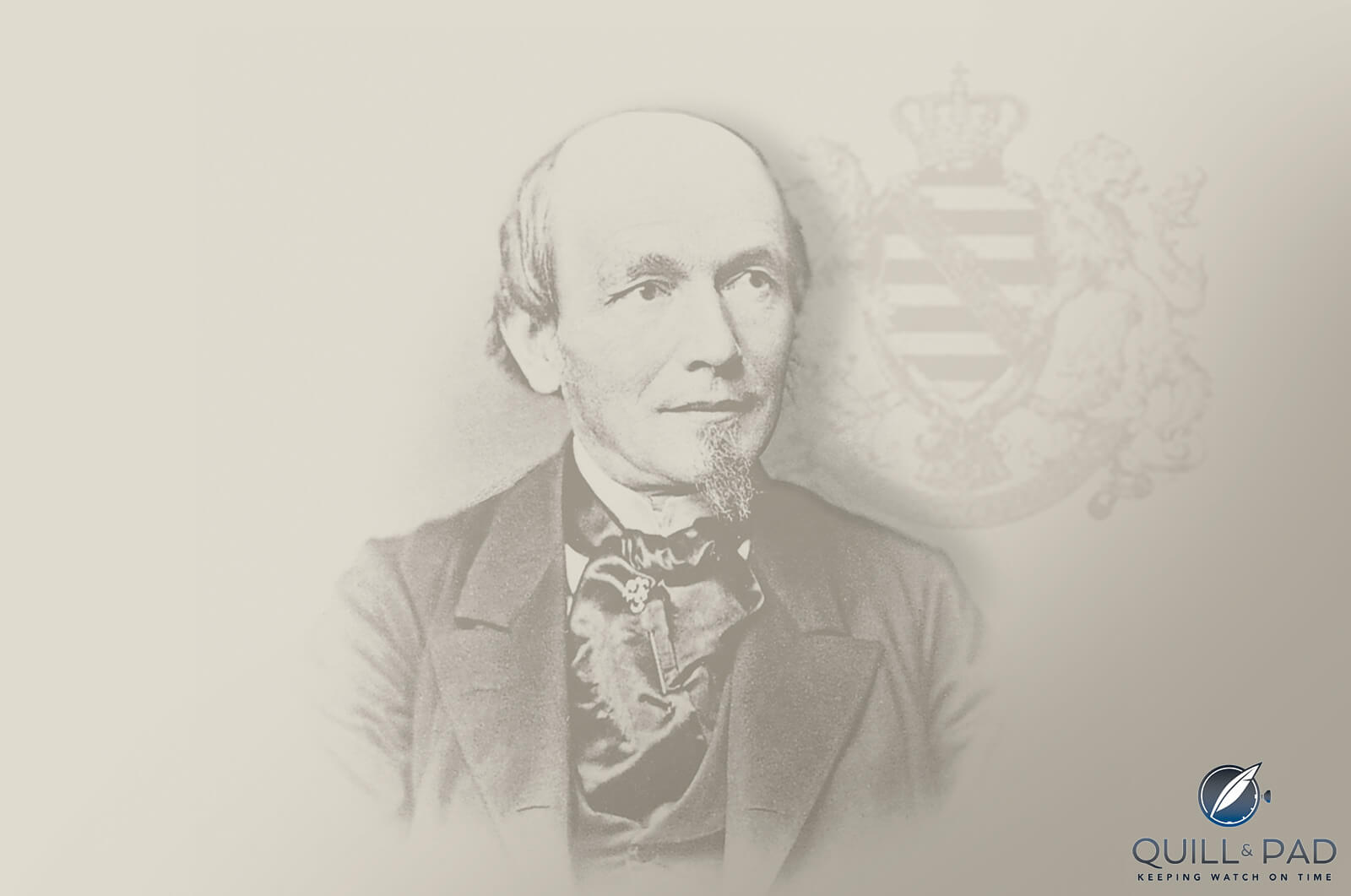

Ferdinand Adolph Lange with the Saxon emblem

Watchmaking in general was on an upswing in Saxony, with clocks and marine chronometers in great demand. It was 1843, and Lange, the court watchmaker in Dresden, replied to the call, sending Privy Councilor von Weissenbach a detailed concept for a pocket watch factory in this poor region.

Lange waited almost an entire year for a reply – to no avail. On May 14, 1844, he re-sent his concept, after which things began to move very quickly. Five days later he received a reply; the contract between Lange and the state of Saxony was officially signed on May 31, 1845.

At the beginning, Lange’s obligations were many but his rewards few. As his intentions were to create an entire grass-roots industry for the greater good of the structurally weak community, he agreed to many duties beyond that of an ordinary businessman looking to start his own business.

Lange agreed to educate 15 new apprentices in watchmaking within three years. These apprentices came directly from the Glashütte area, so Lange looked out the ones seeming to have the most manual dexterity – and many of them were basket weavers. None were trained in watchmaking.

The ministry allotted Lange 6,700 talers (the currency of the time) for start-up, 1,170 of which were set aside for education and tools. The apprentices were obliged to work for Lange for another five years after completing their apprenticeships. During those five years they were required to pay back the government 24 Neugroschen per week (30 Neugroschen = one taler) for their education and tools, which they got to keep.

For some idea as to how much money this might have been, the weekly earnings of a trainee, who worked an average of 12 hours a day, including Saturday, was between three and six talers. Lange was also obligated to pay back his loan of 5,530 talers between 1848 and 1854.

Despite the inadequate, insufficient credit from the government and apprentices not familiar with the work, Lange rented a small workshop on Glashütte’s Hauptstraße (“Main Street”) and planned a yearly production of 600 watches.

Ferdinand Adolph Lange’s first workshop in Glashütte; today it is a Nomos retail location

This is an inordinate amount of watches for the time without large-scale machinery. Lange’s idea was to divide the labor so that each of his employees was responsible for completing certain elements. Division of labor was new in German watchmaking at the time.

Additionally, Lange’s concept included something that remains a key element in contemporary Glashütte: to have the best rate precision possible when the watch leaves the factory. All Lange timepieces were to be regulated and timed before leaving the workshops, also a new concept in watchmaking: up to this point, watches were usually timed and regulated by the watchmaker who sold them at retail.

Another innovation was the measurements Lange used. Until then, the typical size measurement in watchmaking was the French ligne, which is equal to 2.5558 mm. Lange introduced the metric system and used it exclusively in his workshop, even though it wasn’t officially used in Germany for measuring until 1875.

As F.A. Lange was the first to use the metric system in watchmaking, he had to invent some tools like this dixième gauge (photo courtesy A. Lange & Söhne)

Ahead of his time in so many ways, F. A. Lange even invented a few new tools still used today to accommodate the new measuring system.

Growing Glashütte: the four founding fathers

Although Lange’s factory was later to reach worldwide fame, his spirit was selfless: his intention was to create an industry for the greater good.

In light of this, it is easy to see why he did not have all of his apprentices fulfill their obligations to remain in his service for five years. He encouraged them to specialize and become independent after completing their apprenticeships. In this way, the one-man industry in Glashütte would grow into a cottage industry, ever expanding and producing not only independent watchmakers, but specialist suppliers as well.

Glashütte in 1879 (photo courtesy A. Lange & Söhne)

One of the men who Lange could talk into joining his adventure in Glashütte was Friedrich August Adolf Schneider (1824-1878). A former apprentice of Lange’s father-in-law in Dresden – Johann Christian Friedrich Gutkaes – at the same time as F. A. Lange, Schneider was also related by marriage to him as he had betrothed the younger sister of Lange’s wife, Antonia née Gutkaes.

Schneider, Lange’s first “factory foreman,” was the initial watchmaker Lange encouraged to set up a second base of operations. And in 1855 Schneider began producing his own watches, although they were never to become as famous as Lange’s. Glashütter Uhrenfabrik Adolf Schneider was taken over by his son Woldemar Schneider after Adolf Schneider’s death in 1878.

Julius Assmann (1827-1886) came to Glashütte to fill Schneider’s position after Schneider had become independent. In 1852, Assmann founded his own factory – the J. Assmann Deutsche Anker Uhren Fabrik – for the manufacture of precision pocket watches. Assmann was good at his job, and in their time his watches were as well regarded as Lange’s. This company remained in business until 1926. Assmann also married F. A. Lange’s oldest daughter, Marie Antonie Lange, after his first wife passed away.

The Assmann no. 122 is the earliest known watch by Julius Assmann; it is part of the standing collection of the German Watchmaking Museum in Glashütte (photo courtesy René Gaens)

Another two factories were founded in the 1890s: Uhrenfabrik Union Dürrstein & Co. and Ernst Kasiske – though Dürrstein’s didn’t make it past 1926.

Kasiske, a regulator in Lange’s factory, was an early proponent of machine production. For financial reasons he took on a partner in 1904, a reputable wholesaler from Berlin, and together they founded Glashütter Präzisionsuhrenfabrik Akt. Ges. This factory’s annual production was about 1,000 watches.

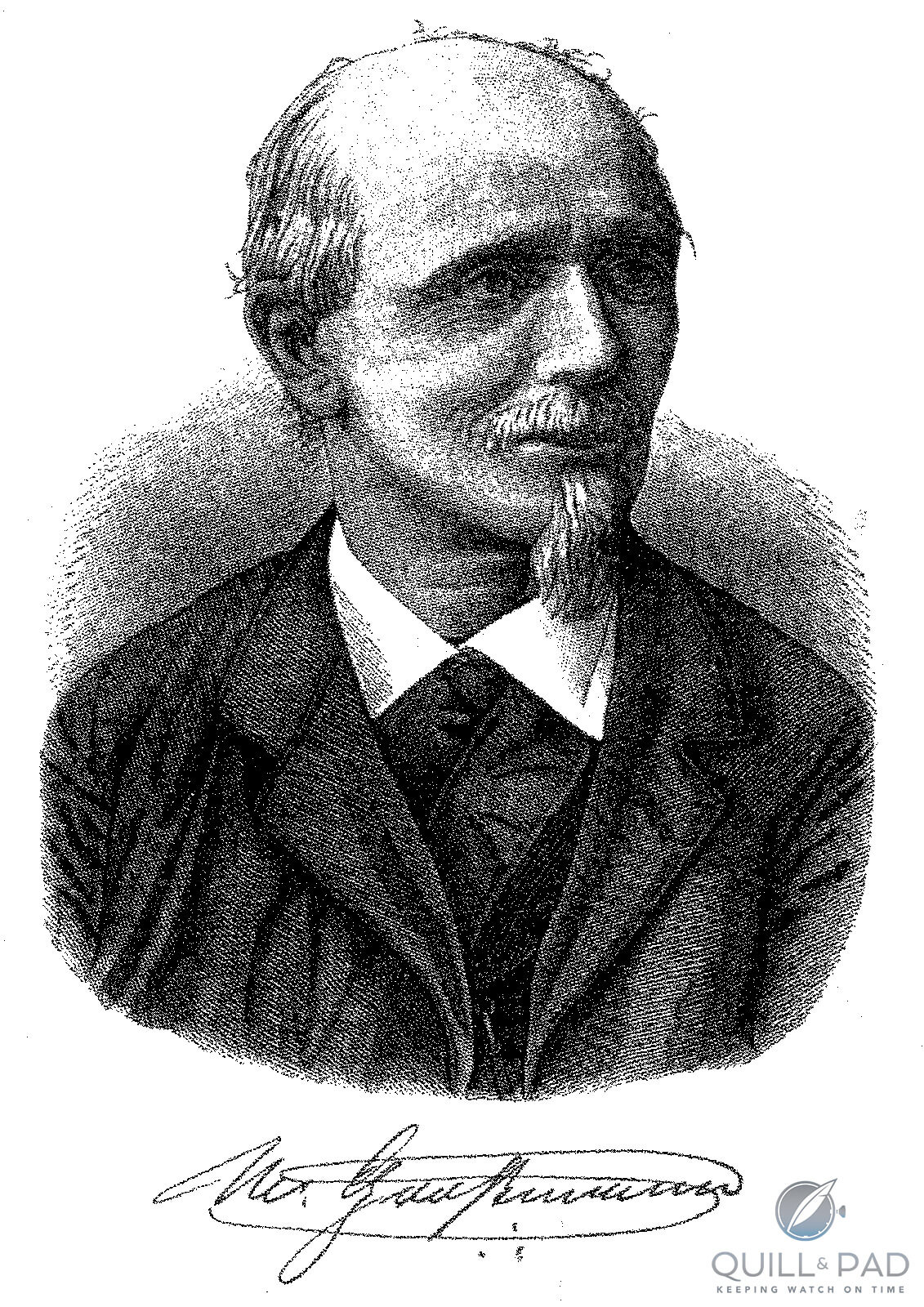

Moritz Grossmann

Perhaps the most important Glashütte watchmaker after Lange, and the fourth of what is known as Glashütte’s “founding fathers,” was Moritz Grossmann. Grossmann founded the German School of Watchmaking in 1878, thus sealing Glashütte’s future fame as a world-renowned center of watchmaking.

The German School of Watchmaking in Glashütte in 1878

Grossmann was also encouraged by Lange to strike out on his own, and he began to manufacture measurement tools according to both his own and F. A. Lange’s concepts, along with precision pocket watches and other accessories. Grossmann was the most intellectual of the industry’s original founding fathers and his first book, The Detached Lever Escapement, was published in 1864 by the Horological Institute in London. This was followed by several more books, making Grossmann famous in international horological circles.

Glashütte’s growing watch industry, and the national and international interest that arose from it inspired a number of new companies both directly involved with watchmaking and in precision engineering. In 1869 Robert Mühle founded his company for the production of measuring instruments – an important supplier in Glashütte as this was the one city involved in horology that was already measuring in millimeters and tenths of millimeters.

Although the watch industry was important for Mühle’s company, it wasn’t his only source of income. He also produced various other measuring instruments, including tachometers and rev counters. Around the turn of the century Mühle also began to manufacture dashboard instruments for automobiles.

Inauguration of Glashütte’s Ferdinand Adolph Lange monument in 1895 (photo courtesy A. Lange & Söhne)

The next generation: capitalizing on the good Glashütte name

An interesting chapter of Glashütte’s history, and one that would eventually repeat itself in a way, opened in 1908.

Capitalizing on the good name that Glashütte had earned due to the hard work of its founding fathers, Nomos-Uhr-Gesellschaft Guido Müller u. Co. Glashütte was founded. Businessman Guido Müller settled in Saxony with his brother-in-law and a watch technician from Biel, Switzerland with an aggressive marketing plan: they presented their watches, powered by Swiss movements, to various reputable persons of the region, asking only for some remarks and a photograph.

From this they made a catalog – the first of its kind. This catalog was sent to solvent farmers and village preachers. The plan was so successful at the beginning that Müller quickly needed to hire ten new watchmakers for regulation and control of the Swiss watches before they left the Glashütte premises.

Nomos Glashütte’s modern headquarters in the town’s former train station

The advertising and catalog texts did not make clear where these watches came from, and at this point Lange’s successors stepped in to protect the reputation of F. A. Lange’s life’s work; Ferdinand Adolph Lange had passed away in 1875 and his sons Richard and Emil now led the company. A. Lange & Söhne and Müller fought through the courts for about five years, but in the end Lange won out and Müller was ordered to be clearer with the written word. That was the end of Guido Müller’s Nomos, and in 1911 the company was liquidated.

This chapter of Glashütte’s history brought to light that not every part of a Glashütte watch was actually manufactured in Glashütte in every case by this time. However, the court’s decision made the law clear: at least 50 percent of the value of a Glashütte watch must come from Glashütte for the name Glashütte to be displayed on the dial. The original Guido Müller Nomos company couldn’t do it and retired from the scene.

World War I

World War I broke out in 1914, leaving a trail of closed factories in its wake. After the war, pocket watches were no longer in demand – it was the newfangled wristwatches that were in vogue.

So not only did the factories have to rebuild from the war, they had to be re-outfitted to accommodate the coming trend.

Although Glashütte’s pocket watches were most precise, Switzerland’s were just as accurate – and much cheaper as the neutral Swiss had already begun producing components by machine. For comparison: a Glashütte pocket watch in a gold case cost 400 marks in 1914, while a comparable Swiss timepiece would sell for 250.

The entire German watch industry came to a full stop during World War I, and around 1917 the country’s united government frantically tried to motivate some of the watchmakers to reopen. It was having a hard time getting Swiss timepieces on credit and could barely supply its uniformed troops with reliable timekeepers.

The future was uncertain, but on November 19, 1918, Deutsche Präzisions-Uhrenfabrik Glashütte e.G.m.H. (DPUG) was registered specifically to manufacture precision pocket watches in a rationalized, industrialized manner, making them less costly than their predecessors. As enthusiastic as the Saxons can be, this new undertaking got off to a quick start. By the end of December DPUG already had 50 employees, even though the new company had troubles getting started with its production from scratch.

Affected by a new sort of plague – sourcing components – Glashütte could not acquire watch crystals. The crystals had previously came from the Alsace-Lorraine region, an industry that had fallen at the end of the war. DPUG was able to import some from Czechoslovakia, but they weren’t enough.

This caused DPUG to found the independent company Uhrengläser deutscher Uhrmacher e.G.m.b.H. in 1919 in nearby Teuchern. In 1921, DPUG built a new factory building to house its 212 employees.

DPUG was creating an output of 350 watches per month – a number that the entire Glashütte watch industry combined had never been able to reach until that point. Things were looking much better for the small town when Glashütter-Feinmechanischen-Werkstätten e.G.m.b.H. was founded in 1923 to make watchmakers’ tools, but as it turned out appearances were deceiving. Both the tooling factory and DPUG went under in 1925.

A silver observation watch by A. Lange & Söhne circa 1919, now part of the German Watchmaking Museum Glashütte’s collection

Meanwhile, A. Lange & Söhne was moving forward with the times, if slowly, to survive the difficult economic atmosphere. The company, now under the leadership of F. A. Lange’s grandsons Otto, Rudolf and Gerhard, developed a new, less expensive watch that went into production in 1928: OLIW, which stood for Original Lange Industry Watch.

The word “Industry” in the name signalized that this was an industrially manufactured watch and no longer one completely produced by hand. The goal here was to make less expensive, contemporary watches and cases. Classic Glashütte watches were just too expensive and old-fashioned for the modern, post-war market.

During the period surrounding World War I, both the Alpina Union Horlogère Glashütte Sachs. G.m.b.H. and Uhren-Fabrikation Otto Estler Glashütter Sa were founded. Both of these companies used Swiss ébauches with select Glashütte components and finished them in Glashütte. Both companies closed after the war, Estler due to the death of its owner in 1924, while Alpina was liquidated in 1922.

A. Lange & Söhne became the only Glashütte company to survive Germany’s economic crisis following World War I. About six million people were unemployed in Saxony at the time.

Between the wars: industrialization, inflation, and a will to survive

At this point, one of Glashütte’s most interesting periods in time commenced. Dresden’s Giro-Zentrale Sachsen, a non-profit bank, had previously allotted DPUG large amounts of credit, which were lost when the company went bankrupt in 1925. The bank decided to found a new company to make up for these losses. Motivated by Pforzheim’s recent successes, the bank’s board was all for setting up a factory to make ébauches in Glashütte.

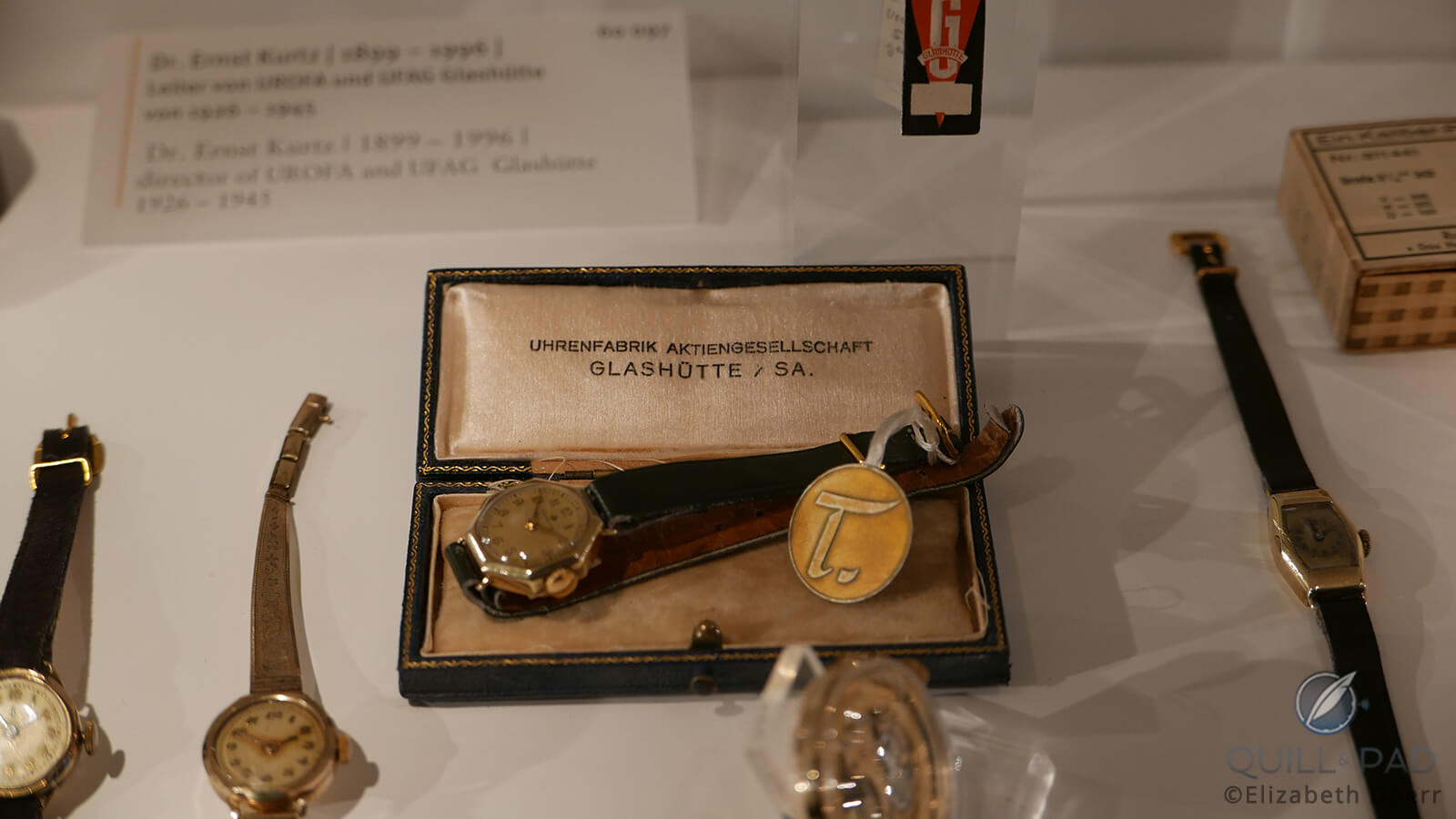

On December 7, 1926 – 81 years to the day after the Glashütte watch industry was officially founded by Ferdinand Adolph Lange – Giro-Zentrale Sachsen founded Uhren-Rohwerke-Fabrik Glashütte AG (Urofa) and Uhrenfabrik Glashütte AG (Ufag).

Dr. Ernst Kurtz (far right) and his development team in Glashütte’s Ufag factory in 1939 (photo courtesy Tutima)

Owned 100 percent by the bank, Urofa was created to manufacture ébauches to be sold both in Glashütte and other regions of Germany, particularly Pforzheim.

Ufag, on the other hand, was called to life to manufacture entire watches using about eight percent of Urofa’s output: these were known as Tutima-level movements and were exclusively manufactured for the company.

Ufag had a great deal of success with its top-of-the line brand Tutima (for more information on this, please see 90 Years Of Tutima: An Abbreviated, Complete History).

The first ébauche factory ever in Germany, Urofa was organized according to Swiss models. Its ébauches comprising base plates with bridges, cocks, winding, and hand-setting mechanisms were delivered, ready for assembly including jewels, decorated surfaces, and galvanic treatment, to special factories and assembly specialists, who put everything together according to the wishes of their clients and added the regulating system. Anything and everything else was done by the “manufacturers.”

Tutima-class watches by Ufag, now part of the German Watchmaking Museum Glashütte’s collection

The two companies, under joint management of Dr. Ernst Kurtz and set up in DPUG’s former buildings, quickly earned good reputations within the watch industry.

World War II

By 1934, Urofa was profitable. But starting in 1938 both Urofa and Ufag were forced to work for the armament industry in preparation for World War II. By 1940, the companies’ own productions were stopped in lieu of working full time for the government.

World War II pilot’s watches from Glashütte (photo courtesy René Gaens/German Watchmaking Museum)

In 1941, Urofa received the task of developing its most famous wrist chronograph: Caliber 59. This is also the movement that would present Tutima with its most famous watch to date, the original 1940s Tutima pilot’s chronograph. Urofa and Ufag manufactured about 1,200 of these watches for the German armed forces per month.

Original 1940s Tutima pilot’s chronograph powered by Caliber 59

Meanwhile, A. Lange & Söhne was also experiencing a sort of renaissance at the end of the 1930s due to increased marine and aviation activity. The professionals in these fields needed precise timepieces for their navigational needs, and Lange manufactured many excellent marine chronometers during this era.

Glashütte bombed to the ground and down comes the Iron Curtain

One hundred years after its founding, the Glashütte watch industry was not only grounded; it was bombed to the ground. On May 8, 1945, just scant hours before the war officially ended, Russian troops bombed Glashütte, leveling most of the factories still located there. What wasn’t bombed was handed over to the occupying forces – including intellectual property – and transported to Russia.

You can’t keep a good watchmaker down, though, and optimistic Saxons are the last to give up, no matter how bad the situation may seem. Regardless of the bleak outlook at the end of World War II, what came after that was actually worse.

Tutima fared the best as Dr. Kurtz fled Glashütte before the war ended, taking Tutima with him to the West. For the full story see 90 Years Of Tutima: An Abbreviated, Complete History.

Lange began producing its Calibers 28 and 28.1 again, the only wristwatch movement A. Lange & Söhne manufactured before the division of Germany, and was able to deliver it in 1949.

Urofa and Ufag tried hard to get back on their feet, producing some watches in 1946 on primitive machines from leftover parts.

A couple of original GUB Spezimatik watches from the 1960s, now part of the German Watchmaking Museum Glashütte’s collection

But it was for naught: on June 30, 1946, most of Glashütte’s watch and precision engineering companies went into the possession of the German Democratic Republic’s “people” to become VEB Mechanik Dresden. VEB stands for volkseigener Betrieb, the “people’s company.” VEB Urofa existed independently for a while, though, and by 1947 could once again begin producing serially.

But on July 1, 1951, VEB Glashütter Uhrenbetriebe (GUB) was founded, and the rest of Glashütte’s independent watchmakers were all expropriated and herded into the one huge conglomerate. The companies making up GUB were as follows: VEB Urofa including Ufag, VEB Lange, VEB Feintechnik (formerly Gössel u. Co.), VEB Messtechnik (formerly Mühle & Son), VEB Estler, VEB Liwos (formerly Otto Lindig), and the Glashütte School of Watchmaking.

Formerly Mühle & Sohn and now Nautische Instrumente Mühle Glashütte, this photo shows production at VEB Messtechnik around 1950 (photo courtesy Mühle Glashütte)

During the time of communist East Germany, GUB was the only watch company in Glashütte. It was a monstrously large concern, employing about 2,000 people. GUB continued to manufacture mechanical watches, even automatic timepieces from around 1954. When the quartz watch hit the Swiss industry in the late 1960s, GUB also figured out quartz technology for the East Bloc.

German reunification leads to the modern age

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and ensuing German reunification also brought about another set of massive changes for Glashütte.

Fall of the Berlin Wall (image courtesy npr.org)

Walter Lange, great-grandson of F. A. Lange and a watchmaker in the family company, had fled to the West after the war. The new political changes, including the fall of the Berlin Wall, brought about the long-awaited opportunity for him to re-establish this most traditional of all Glashütte companies.

With the help of the business genius of Günter Blümlein, a man who had already reorganized IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre following the quartz crisis, and the financial backing of the Mannesmann-VDO group, who owned the two above-mentioned manufactures, on December 7, 1990, exactly 145 years after its initial founding, Lange was able to re-establish his family’s company in Glashütte where it belonged. The first modern A. Lange & Söhne collection appeared in the marketplace in 1994 (see Why The A. Lange & Söhne Tourbillon Pour Le Mérite Is One Of The Most Historically Important Wristwatches for more on that).

Günter Blümlein and Walter Lange at the F. A. Lange memorial in Glashütte in 1991

Not to remain the only luxury manufacture in the small town, the East German giant Glashütter Uhrenbetriebe was bought by Heinz W. Pfeifer and partners in 1990, a businessman from a neighboring western state. Pfeifer restructured GUB so much that it has become a more than respectable, profitable representative of Glashütte in the world’s markets, with its first new watch issued in 1991.

Since GUB was originally the conglomerate of all of the companies left in the town before expropriation, GUB still owned the rights to these names. In addition to creating the Glashütte Original brand, GUB also re-founded the Union brand as a “little sister” in typical Rolex/Tudor tradition. This company gained so much standing in the industry for its horological excellence that it was purchased by the world’s largest watch company, Switzerland’s Swatch Group, in 2000.

The fifth and fourth generations respectively of Robert Mühle’s company: Thilo Mühle (left) and his father Hans-Jürgen Mühle in 2014

Hans-Jürgen Mühle, great-grandson of Robert Mühle, worked in distribution at GUB, becoming one of five managing directors before the fall of the Berlin Wall. After GUB was successfully sold, Mühle turned to re-founding the company that bore his own name: Nautische Instrumente Mühle Glashütte.

And that renegade – Nomos – experienced an exceptionally fruitful renaissance (in name only) when Roland Schwertner, a Düsseldorf businessman involved with watches, saw the opportunity to create something special. He bought the name Nomos and founded a small watch company in Glashütte in 1990, becoming the first brand in Glashütte after German reunification.

One of Nomos Glashütte’s four buildings in Glashütte: assembly takes place at the so-called Chronometrie (photo courtesy Nomos)

History seemed to repeat itself at the start, though, as Nomos watches were powered by the Swiss Peseux Caliber 7001, but a historical reminder from A. Lange & Söhne and GUB (Glashütte Original) quickly resolved the situation. Nomos Glashütte’s timepieces are now so evolved that they are powered by manufacture movements.

For Schwertner, it was important to maintain the original spirit of Glashütte. And so Nomos grew so much that it has spread to several locations around the town, one of them being the city’s first retail outlet for a Glashütte-made watch. And this little store for Nomos Glashütte’s watches is located at Hauptstraße 12 – in the same building where F. A. Lange began the entire Glashütte industry 175 years ago.

Nomos Glashütte’s retail shop is located in Ferdinand Adolph Lange’s first workshop (photo courtesy Nomos)

Other brands have come, some have gone, but some have remained. Notable “newcomers” include Wempe Glashütte and Moritz Grossmann.

Since the re-introduction of western capitalism in Glashütte, the town has experienced myriad changes. The obvious economic upswing brought a barrage of new buildings and reconstruction with it.

But Glashütte once again had to contend with disaster: in August 2002 the flood of the century – for all of eastern Europe – caused a dam to break above the town in the hills of the Erz range, swelling both the usually tame Prießnitz and Müglitz rivers and causing a cascade of raging waters to ravage the town. But in typical Glashütte tradition, the 2,500 residents and their helpers got back up, dusted themselves off, and re-started the machines that worked.

Today, the city is dedicated almost fully to watches and is home to modern machinery, big brands, and famous horology. Its watch industry is growing, and new suppliers are being attracted to the region and its outskirts.

A selection of modern movements currently produced in Glashütte (photo courtesy Holm Helis/German Watchmaking Museum)

And with the number of fine products the city now turns out, it will most certainly continue to present the horological world with high-quality products made in Saxony for a long time to come.

Modern Glashütte (photo courtesy Holm Helis/German Museum of Watchmaking)

Happy birthday, Glashütte: 175 years look really good on you!

For more detail on the modern era of Glashütte please see Made In Germany: The Glory Of Glashütte.

You may also enjoy:

90 Years Of Tutima: An Abbreviated, Complete History

How The Wall Came Tumbling Down: Made In Germany

Made In Germany: The Glory Of Glashütte

Film: A. Lange & Söhne “A Legend Comes Home”

How Does Nomos Glashütte Make A Beautiful Watch With Manufacture Movement For Under $3,000?

‘Made In Glashütte’ Vs. ‘Made In Germany’: What Puts Them Together, What Sets Them Apart

Q: Who Was Alfred Helwig? A: Inventor Of The Flying Tourbillon

Sixties Iconic: Glashütte Original’s Richly Multicolored Homage To Vintage East German Style

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

This article made my day – on a day like October, 3, 2020 it is such a good read. Thank you very much. It gives such a rich, lively, and complete overview and time-travel about German watchmaking in the Glashütte region. Excellent knowledge and background for visiting the exhibition in Deutsches Uhrenmuseum (‘How it all began’). I am so impressed to see the b/w image of the huge ceremony (inauguration 1895) for the Adolph Lange monument opposite to Walter Lange and his monument unveiled recently.

‘Das habe ich wieder einmal sehr gerne gelesen’ dear Elizabeth.

Greetings, Thomas

Thank you so very much for the kind comments! I can, by the way, heartily recommend visiting the new exhibition in the museum, which I had the pleasure to do while I was there. I hope to post something on it soon.

Fascinating read, learned some new things. Thank you Elizabeth.

yes, a lot of information spread over many texts finally together in one nice article. Great, isn’t it.

My pleasure! Thank you for taking the time to read it.

I am truly grateful for this informative article. This is an excellent and comprehensive article-length history, a real gift to your readers. Thank you.

Thank you so much for your kind comment!

This is a very well researched article, thank you!

One comment though: Ernst Kasiske is not written with double “s”.

Thank you for catching that, I have corrected it.

I love this article, It transports me to a wonderful

time, I have a love of watches, but I only like mechanical, or automatic . I have a Glashutte from 1940’s and a Bulova made in Germany in the 1970’s among my collection, I always ben fascinated by mechanical watches thank you for a great and beautiful

article. Beautiful Town, Glashutte . Hope to visit some time in the near future.

Thanks for the article. Great read!

Learn something new everyday.

Just doing research on a pocket watch, made by Adolf Schneider sn 2118 Dresden. My father & grandfather

were watchmakers, emigrated to USA in 1927. Grandfather and father were from Freiburg. They both opperated a shop in Chicago untill the 1970’s. Very through history of Glaschutte and watchmaking history.

Thank you:

John Tobusch

Hi, this is a very interesring story.

My great great grandfather was Leopold Brauer (b. 1821), he was from Sachsen Germany. Leopold and his son (Oskar Brauer, my great grandfather) were both watchmakers. Is there a website or books where I can research about the students of the German School of Watchmaking?

That’s a really tough one. The best I can probably do is point you in the direction of Kurt Herkner, who wrote the two volumes entitled “Glashütter Armbanduhren.” Unfortunately, he has no website and I have no contact info for him. He is the only person I know with knowledge of the school like you are looking for.

Thank you very much!

I have a pocket watch looking to find out how much its worth

excellent read. i found this page, trying learn who Augst Stulh (i just learned that “stuhl” translates to chairs, its the only spelling i have to utilize, this August fellow was from germany and i assume in the clock and watchmaking and repair industry my uncle was his apprentice for 2, in mid to late 1920s. i believe in amerika, any info that might aid in pointing me in the correct direction to look and learn is much appreciated thank you

I have inherited my great grandfather’s

Glashutte pocket watch.

The serial number is 8405, so fairly early.

Can anyone give me some idea of when it was made?

Thank you.

You should take a photo of the dial side and the movement and send to Glashutte Peter. Or attach a few photos here and we will see if we can help.

Regards, Ian