by Ken Gargett

In this occasional series on great wines of the world, today I am looking at an extraordinary pigeon pair: Lindeman’s twin bin wines from 1965, the Hunter Burgundies Bin 3110 and Bin 3100.

It is possible that both these wines are exceeded by the 1959 vintage, Bin 1590, but that wine is so rare now that one has to wonder if more than a couple of bottles remain in existence, if that. I tasted it once, about 15 years ago – what a wine. Some years ago, Lindeman’s was quoted as saying that it knew of only one remaining bottle of the 1959. Who knows if it still exists today?

Lindeman’s 1965 Hunter River Twin Bins 3110 and 3100

There is no question that Bin 3110 and Bin 3100 are just as deserving. Thanks to far-sighted friends who picked them up for peanuts when released, I’ve been very fortunate to try them on a number of occasions and they are truly world class.

A few decades ago, other than an occasional Grange (Grange Hermitage, as it was known then), Aussie wine was a sea of average fortifieds, rustic reds masquerading under European place names, tanker loads of bag-in-a-box, and wines bearing names such as Emu Wines – a possible forerunner to the “critter” wines that followed.

These were wines that Maurice Healy in his wonderful Stay Me with Flagons described as “detestable” and “horrible” and gave Monty Python easy ammunition.

However there was always more to it, gems to unearth for those prepared to make the effort.

The amazing wines made by Maurice O’Shea at Mt. Pleasant in the Hunter Valley north of Sydney in the 1940s and 1950s; the extraordinary Woodley’s Coonawarra Treasure Chest series also from the late ’40s and ’50s; Mildara’s Peppermint Pattie (a Coonawarra Cabernet from 1963); Wynn’s Michael Hermitage (Shiraz) from 1955; Penfolds’ Bin 60A from 1962, a blend of Kalimna Shiraz and Coonawarra Cabernet considered by many to be the finest wine ever made in Australia; Grange itself; and a trio of Shiraz (dubbed “Burgundy” at the time) from Lindeman’s in the Hunter: Bin 1590 from 1959 and the twins from 1965, Bins 3100 and 3110.

These offer a glimpse into a rich and complex history of wonderful wines.

Today, all these wines bring huge prices on the very rare occasions that they appear at auction. As Andrew Caillard MW of Langton’s Auctions said, “Today it is easier to buy 1945 Château Mouton Rothschild or 1921 Château d’Yquem than 1965 Lindeman’s Bin 3100.”

Unfortunately, many of these amazing Australian wines are now hit-and-miss propositions with the exception of these twins from 1965, both of which inevitably show superbly as though they have discovered a vinous fountain of youth.

The last time I tasted the twins was around a decade ago, although friends had bought good quantities when they were first released (I’m not sure exactly when that was at some stage in the late 1970s, but it was as mature wines, not the normal course of events).

One or the other of the pair would often appear at lunches, and they never missed a beat. One evening, a friend brought a bottle to dinner at a restaurant. At the neighboring table was a another friend who just happens to be one of the world’s most famous wine critics and international wine judges.

I took him a glass and asked what he thought. This was an Australian Shiraz that was around 40 years of age at the time. Granted, it was in brilliant condition, but I was a little stunned when he picked it as one of the Guigal Single Vineyard wines from Côte-Rôtie, around two to three years old. He was even more stunned when it was unveiled, especially as it was a wine he had tasted many times.

Lindeman’s 1965 Hunter Shiraz Twin Bins 3100 and 3110: Karl Stockhausen and some mystery

This pair of wines has always been shrouded in mystery, and as Karl Stockhausen was present when I last saw them, it was a great chance to find out what I could. Stockhausen was the man who made them back in 1965.

Karl Stockhausen (right) tasting wine in 2012

Now in his nineties, Stockhausen was born in Germany in 1930. He migrated to Australia at 25 to study accountancy and then joined the team at Lindeman’s as an office clerk. Even though he was completely lacking in experience he was offered the winemaking role in 1961.

Why? Because he was seen as someone with meticulous attention to detail.

A drought year in the Hunter, 1965 was considered a large yet excellent vintage. This would normally be good news, but in this case it created a problem. The white varieties, dominated by Semillon, were all picked in early February, and Lindeman’s simply did not have the space to bring in any more grapes.

All its vats were needed to ferment the whites. So the Lindeman’s team simply left the red grapes to hang on the vines. It wasn’t until late that month that harvesting of them could begin. Fortunately, conditions had remained fine – rare for the Hunter at this time of year. So the grapes that made these wines spent far longer on the vine and were far riper than was usual.

The vineyards in question were brought into the Lindeman’s portfolio in 1912, but it is believed that the vines were actually planted back in the 1870s.

The grapes came in at 15 to 16 baumé and were then fermented in open concrete vats before being pressed into a mix of 500- and 1,000-gallon casks. The wines were taken out of casks and bottled in less than 12 months simply because the winery needed the cask space for the next vintage.

Stockhausen believes that one of the reasons for the 1965 Twin Bins showing such consistency over the years was that, unlike the previous stellar vintage of 1959, the handling of the ’65s was done much more quickly. The 1959s were much patchier.

Lindeman’s winery in the Hunter Valley, Australia

Lindeman’s 1965 Hunter Shiraz Twin Bins 3100 and 3110 and the little-known soupçon of Pinot Noir

Lindeman’s usually made three versions of its Shiraz (which went under the tag “Burgundy” at the time). The decision would be made in the winery, the allocation depending on the quality of the various casks. Stockhausen said that in 1965 the quality was so uniform across the board that he only made the two wines, and even then there was hardly any difference.

At the time, he wondered whether there was any point in splitting the wines into two lots. Stockhausen doesn’t recall just how much of these wines was made but he does remember that it was “an unusually large vintage.”

There was, however, one slight difference between the pair. Lindeman’s had a very small patch of Pinot Noir behind the winery, and the juice from these grapes would always end up “somewhere.”

Pinot Noir was almost unknown in Australia at the time, and the Hunter, despite the assertions of some locals, is a most un-Pinot-friendly wine-growing region. Labelling verisimilitude was universally a little laxer in those days, and Lindeman’s would think nothing of tossing it in a blend without mentioning it in the details. It was never any form of attempted deceit.

Len Evans, writing about these wines when they were released toward the end of the 1970s, made much of the addition of this Pinot Noir to one of the wines. This was more a Pandora’s box than treasure trove as, for many years, it became the focus of discussions whenever the wines were mentioned. Reports of the percentage of Pinot varied, but there were some suggestions that it went as high as between five and ten percent.

In truth, Lindeman’s felt it the most minor of issues, and today it is more a trivial pursuit than a matter of genuine importance. Stockhausen can’t even recall which wine had the Pinot Noir injection and says that it totaled a mere 0.5 percent of whichever wine it was. Had Evans not made it public, it would never have occurred to Lindeman’s to do so. Memory tells me that the Pinot Noir went into Bin 3100, but I certainly would not put any money on it.

The wines themselves were much bigger and more powerful than usual Hunter reds, especially Bin 3100, with alcohol levels approaching 15 percent, rather extreme for the day. Lindeman’s felt that it was not ready for release until the late 1970s. When the wines were finally released, Stockhausen thinks that the price was less than AUD$12 a bottle, a bargain compared to the many thousands per bottle they attract today.

Bin 3100 was bottled in a Bordeaux bottle while Bin 3110 went into a Burgundy bottle. Stockhausen says that there was no significance in this – and it certainly had nothing to do with the dollop of Pinot Noir. It was simply what was to hand.

He remembers that if there was a difference in the wines in the early days, it was that 3100 was considered the bigger, more forceful wine at the time. And this has been amplified over time. It is undoubtedly the more muscular of the two, while the 3110 is all about elegance. Stockhausen believes that they will still be drinking superbly for many years to come.

If ever the opportunity to try either of these wines should present itself, grab it. Not just as compelling evidence that Australia really does have vinous history that includes some truly great wines but simply because they are world-class wines, still in glorious form.

These notes are from a decade or so ago, but I expect that well cellared examples in good condition will not have changed that much. They are that sort of wine.

Tasting notes Lindeman’s 1965 Hunter Shiraz Twin Bins 3100 and 3110

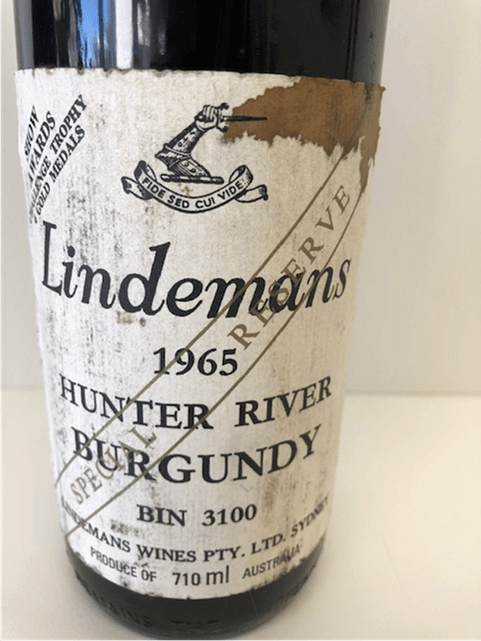

Lindeman’s Hunter River Burgundy Bin 3100, 1965

Undoubtedly the bigger of the two wines, Bin 3100 has serious power and concentration. It is a wine brimming with life and not showing the slightest inclination to slow down or settle into a gentle dotage.

Lindeman’s 1965 Hunter River Twin Bin 3100

Fully ripe and rich, there are notes of roasted meats, spices, a little chocolate, and coffee grinds. Also hints of licorice and brambly dark fruits. Immaculately seamless and with a very, very long finish.

There is still an extensive tannin structure in place. A muscular, firmly structured wine that has many years ahead of it. Past notes suggest that it plateaued some time ago and seems unlikely to be going anywhere for some time. 98.

Lindeman’s Hunter River Burgundy Bin 3110, 1965

It is always a dangerous analogy, but if 3100 can be considered the muscular and more masculine of the pair, the 3110 is very definitely the more “feminine” wine. It is the personification of ethereal elegance.

Lindeman’s 1965 Hunter River Twin Bin 3110

Wonderfully complex, with a kaleidoscope of flavors coming in ever-evolving waves. There are still the exotic spice characters, but it is more floral with mocha and red fruit notes. Sweet earth, old tobacco, and dried vegetation. Sweet leather notes.

An array of flavors that can only emerge with maturity yet, again, this wine is fresh and amazingly youthful. And certainly destined for a very long life. It has none of the force of the 3100 but instead offers a graceful, lingering quality. The tannins are gentler, settled.

An Australian wine ranking with the very best that this country has ever produced. 100.

For more information, please visit www.lindemans.com.

You may also enjoy:

Penfolds Bin 60A 1962: Australia’s Greatest Wine Ever (Or Certainly A Serious Contender)

Penfolds 2016 Grange And G4: Superlative Wines, Well Deserving Of 100 Points. Each!

Penfolds G3: Making Grange, Already One Of The World’s Greatest Wines, Even Better

Rutherglen Muscats: Fortified Liquid Delights From A Historical Australian Wine Region

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Amazing to see these wines again. I have had a few of both of them. For myself and a couple of friends they were our first ‘great wines’. Wines to aspire to and save for. They were difficult to find and from memory close to A$40. Wow! Early 80’s?

I would love to try one now.

Ken, I think you have summed them up for many.