There are many categories of people who partake in the experience of watches. I like to give some of them labels like watch enthusiasts, watch collectors, watch fanboys (or girls), watch connoisseurs, watch geeks, and watch-aholics.

Each category shares aspects with the others, but they all have their own distinct variety of enthusiasm in which people focus on different avenues for their passions.

For instance, a watch connoisseur (some might use the term “watch snob”) grades watches based on provenance and technical achievement, usually resulting in a different ranking order than the other groups or even other connoisseurs.

A watch fanboy (or girl) usually has a brand or even more specifically a model that they absolutely adore and choose to wear only that. Many of these also happen to be some of the most passionate debaters concerning which year of a particular model was indeed the best or most representative of what that watch was about.

Most people seem to be members of more than one category, and even in these groups there are factions that disagree with others over titles.

Exclusivity can become heated

Then there are those that somehow fall outside of these categories with their main intellectual interests. I group these people, myself included, into the horology nerd faction. While horology nerds share aspects of all the groups, they also go above and beyond in their passions, usually in deference to the field of horology over a specific brand or ideology.

I name myself to this group for the simple fact that I cannot say I have a favorite brand, a favorite watch, or a favorite style.

What fascinates me more than anything is watchmaking itself.

The art, skill and science of watchmaking

The art, skill, and science of watchmaking are truly astounding. Even just in the fact that watchmaking has actually helped to develop machining technology for the rest of the world. When your components need to be more precise than almost anything in existence, you will always push the boundaries of fabrication, metallurgy, metrology, and machine design.

Not many machines or pieces of equipment were more precise than those used in horology until the late eighteenth century, and even then techniques were borrowed from the people who had been working in microns for decades. The latter were probably working in microns even before they knew what microns were!

Random metrology nerd side note: The term micron, which denotes the millionth part of the meter, came into use between 1879 and 1967, though the official term was, and remains, micrometer. “Micron” is still used widely, especially in the U.S., to help differentiate between the unit of measure and the measuring device, which in the American spelling becomes micrometer, and is a homograph of the unit of measure.

The reason I want to talk about my definitions of watch love is because I want to talk about one of the biggest horology nerd projects going on right now: Le Garde Temps, Naissance d’une montre. Translated this means “The Timepiece, the birth of a watch.”

In practical terms it might as well be named Incredigasmically Awesomeable Horologicism. Yeah, it’ll catch on; it just rolls off the tongue!

If you are a true horology nerd and haven’t been living under a rock for the past couple years, then you will have heard about this “little” endeavor between some of the best names in watchmaking today.

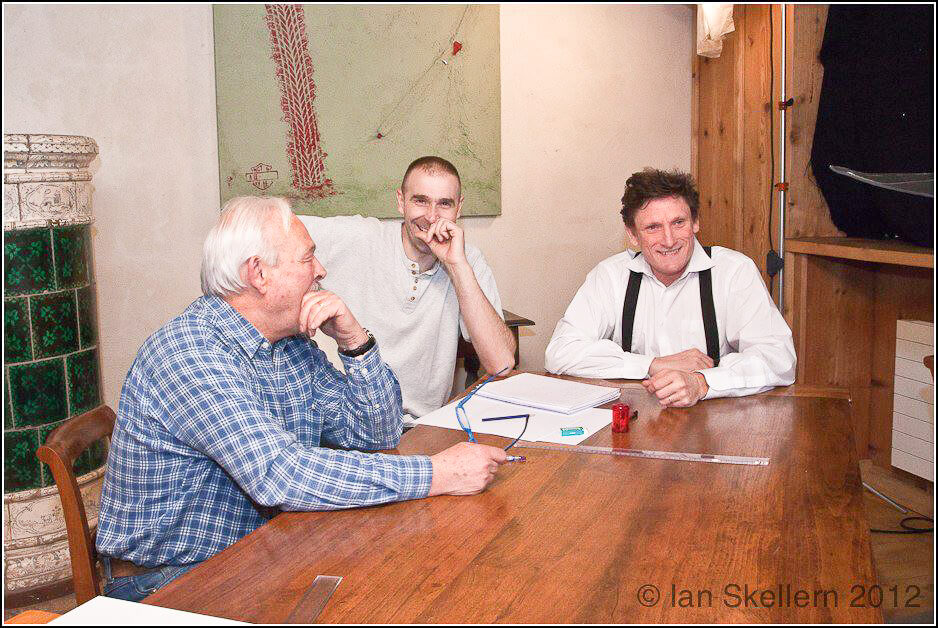

In case you haven’t heard, this project combines the likes of Robert Greubel, Stephen Forsey, Philippe Dufour, and the soon to be horology household name Michel Boulanger, who is the luckiest watchmaker on earth right now if you ask me.

He was handpicked by Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey to basically receive ALL of their knowledge about traditional techniques, processes, equipment, and theory to safeguard for future generations. With Boulanger a teacher at the Paris Watchmaking School and boasting a history of restoring antique timepieces, he fit the requirements for becoming a horological reliquary perfectly.

Horological reliquary

The purpose of the project is to teach and disseminate traditional practices for watchmaking to ensure that they aren’t lost to modern automation and industrialized fabrication. The skills of a craftsman need to be taught widely should they hope to survive scientific progress intact.

The knowledge of how to build a watch by hand requires the mastery of over 30 different crafts, all of which are specializations belonging to separate individuals.

Today they may also belong as a body of knowledge to a whole organization – such as a complete manufacture like Jaeger-LeCoultre or the Richemont Group as a whole – with the specifics not in practical use by any one person.

This is a dangerous way to operate from the standpoint that only very few people can individually practice the completion of a whole wristwatch. A past critic of this was the esteemed Dr. George Daniels who, as one of very few in history, mastered 32 of the 34 traditional crafts associated with fine watchmaking. His process eventually became known as the Daniels method and it is a historical precursor to this incredible project.

I cannot verify this for sure, but with the passing of Daniels in late 2011, the Garde Temps project stands poised to ensure what he had preached for years: that to truly be a watchmaker and to protect the techniques of your craft, you must master all of them, and then proceed to teach them to as many worthy students as possible.

Another proponent of this ideology is the legendary Philippe Dufour, so naturally he is an impeccable fit for this endeavor.

Upon completion of this three-year project, Boulanger will return to teaching and slowly incorporate all of the lessons from Greubel, Forsey, and Dufour into his own lessons, thus guaranteeing a dissemination of the time-honored techniques of classic watchmaking.

Beside enabling a single man to learn all of the skills to fabricate a watch entirely by hand, this project is first and foremost about knowledge, tradition, and safeguarding the future by remembering the past.

Remembering the future

That is why this project means so much to so many people, and why it is something I am entirely jealous of every time I see an update on its blog. If you happen to follow me on Instagram (@jmunchow) or Twitter (@joshuamunchow) – #shamelessselfpromotion – you will know that I am dreaming of becoming a watchmaker one day. I am currently even building my own watch (case, dial, and hands with an ETA movement) and feel very much like a kindred spirit with Boulanger.

While he is an accomplished watchmaker, restorer, and teacher who is now taking the role of pupil and greatly expanding his current skill set while challenging himself at every turn, I am a skilled fabricator and machinist, with a history of crafting small, intricate things. And I am also stretching my abilities and learning as much as possible from my watchmaker friends, and my mistakes.

The updates on the Le Garde Temps, Naissance d’une montre page mainly consist of step-by-step overviews of Boulanger creating every single component, while also demonstrating mistakes, corrections, and every point in which a learning experience has popped up. These are almost constant, which I can attest as being a big part of making anything new and using new techniques.

Boulanger has self-imposed limitations for creating components with minimal use of three-dimensional technology (everything is drawn and calculated on paper first) and without the use of CNC machining or any automated process.

Vibrating a hairspring. The finish of the tweezers on the tool from which the hairspring is suspended are particularly important to get the precise vibrating point for the active length of the spring, which ensures good precision timing

Connected

This is another point where I feel very connected to this project. I have very advanced capabilities at my disposal, but I am choosing to utilize as many hand processes as possible. No CNC machining and nothing automatic, which definitely adds to the time to create components and assure accurate dimensions. A recent set of posts on the Le Garde Temps page discusses the seven stages of creating a mainspring barrel, mentioning how parts have been destroyed or rendered useless by the slip of a cutter or simply dropping the piece.

I myself have discarded three dials that took eight to sixteen hours apiece to complete simply because a measurement was off, a cut went too deep, or in one case a critical hole was destroyed when a very tiny drill broke and marred the piece deeply.

Michel Boulanger has stated that this project has deepened his understanding of patience as he has had to endure many hours of slow, tedious work to achieve something that, using modern methods, might only take a fraction of the time.

A great example of this is manually polishing pinion leaves with a bow and vice-mounted holder. Automated machines exist that can polish all surfaces of a pinion in minutes, but there the skill is simply in setting up the machine, not being able to feel when something is being polished evenly and having the dexterity to do it in the first place.

Passing on skills

These are the skills that Greubel, Forsey, and Dufour have set out to pass on, and with the collaboration between these giants of men, hopefully they will find a good home inside Boulanger’s head and eventually the hands and brains of his pupils.

This year at SIHH, the project released the first prototype of the hand-wound tourbillon movement, much to my excitement. After reading and watching the progress for two years, it is incredible to see something come to life when you know the intense amount of work that has gone into it.

Enjoyably for me, the prototype is in a working state but not a perfectly finished one. It has machined surfaces instead of côtes de Genève; it shows tooling marks instead of perlage; only surfaces required to be polished for their functionality are so and that is how a completely handmade prototype should be.

It is a great indicator as to how much effort has gone into this piece already and how much more needs to be expended for something most watch connoisseurs would deem acceptable. Handmade watchmaking is truly a gargantuan feat when modern equipment is taken out of the picture and efforts are made to stay as traditional as possible.

I bow down to these gentlemen and their efforts to preserve the past while insuring the future. If I might make one comment to the group as a whole: Please consider my application for any future positions or as a successor to Michel Boulanger. The U.S. could really use someone with the knowledge you are imparting to help revive watchmaking on this side of the pond – which, by the way, is no longer necessarily a statement to be scoffed at. Even if you are a watch snob.

For more information on the Le Garde Temps, please visit http://www.legardetemps-nm.org/en/ and/or follow the project on Facebook and Twitter.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] l’Instant de Vérité: The Most − If Not The Only − Fully Handmade Watch Available Today The Le Garde Temps Project: A Horology Nerd’s Dream Come True A Hero’s Journey Begins And Ends: Naissance d’Une Montre, Le Garde Temps http://www.timeaeon.org […]

-

[…] Dufour were also ready to launch the Le Garde Temps – Naissance d’une Montre project (see The Le Garde Temps Project: A Horology Nerd’s Dream Come True) that year, which also had the aim of safeguarding and transmitting traditional watchmaking […]

-

[…] For more information, please see The Le Garde Temps Project: A Horology Nerd’s Dream Come True. […]

-

[…] resulting from the Dufour/Greubel/Forsey trifecta, was simply too much for us to resist. (See The Le Garde Temps Project: A Horology Nerd’s Dream Come True for more […]

-

[…] For more on Dufour, please read Why Philippe Dufour Matters. And It’s Not A Secret and The Le Garde Temps Project: A Horology Nerd’s Dream Come True. […]

-

[…] skills and techniques involved in creating a high-quality timepiece entirely by hand. Read The Le Garde Temps Project: A Horology Nerd’s Dream Come True for […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

… Drool…

Awesome article Josh! I’m looking forward to watch-ing (I’m slightly embarrassed by that – but not really) the progress unfold. As well as the progress in your own piece!