The United States of America has a “secret” past in watchmaking that most people don’t know about.

Yes, I am serious. And, no, it has nothing to do with the Freemasons.

At least I think it doesn’t.

But it does have a lot to do with what Americans are good at: mass manufacturing.

So, to set the scene properly, let’s look back to the 1850s and circumstances that actually led to the demise of England’s dominance in the world of watches (think John Arnold, Thomas Mudge, John Harrison, etc.).

Automated case machinery

Watchmaking went hand-in-hand with the United States’ emergence as an industrial powerhouse and was of great importance to the rise of the large continent’s railroads.

The railroads are a story for another day. Today, we’re here to talk about machines that furthered the business of American watchmaking.

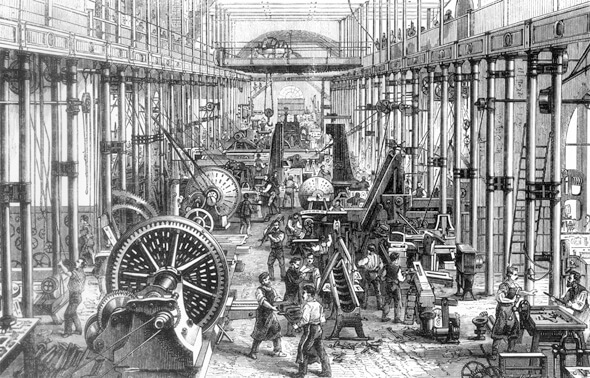

It was around 1850 that American firms began using automated machinery to mass produce watches of relatively good quality with interchangeable parts – a major innovation of the time.

American mass production was driven by automated, high-precision machines that produced large quantities of identical – thus interchangeable – components. The system was developed by the military during the American Civil War (1850–1875) and was also known as “armory practice.”

This American way of manufacturing was fairly well established by the 1870s. It allowed manufacturers to make pocket watches that were much lower in price at the time than the portable timekeeping devices that were mainly imported from Europe.

According to various sources, the first significant American development in the art of case making was achieved by James Boss of Philadelphia. Boss formed cases by rolling sheet metal, which increased molecular density, as opposed to the era’s traditional method involving soldering and cutting.

His patent of May 3, 1859, revolutionized the watch case industry by enabling the production of less expensive, yet stronger, cases that were far less subject to wear and took less labor to produce.

In 1875, Boss’s rights to the patent were bought by Hagstoz & Thorpe, a Philadelphia-based watch case company established by two experienced case makers. Within a decade this company was making about 1,500 cases per day.

And dials, too

Dials from the early 1850s were mostly imported from England, with some coming from Switzerland. In the 1860s, U.S. dial making took a significant upward turn when English people began immigrating to the United States in high numbers. Other American dial makers went to England for training.

American companies and artisans also produced fairly elaborate dials that were created using a variety of techniques. According to historical findings, some were so complicated as to require about 100 separate production operations.

The most tedious step of all was without a doubt the miniature painting then popular, which involved the use of very fine brushes comprising only a few animal hairs.

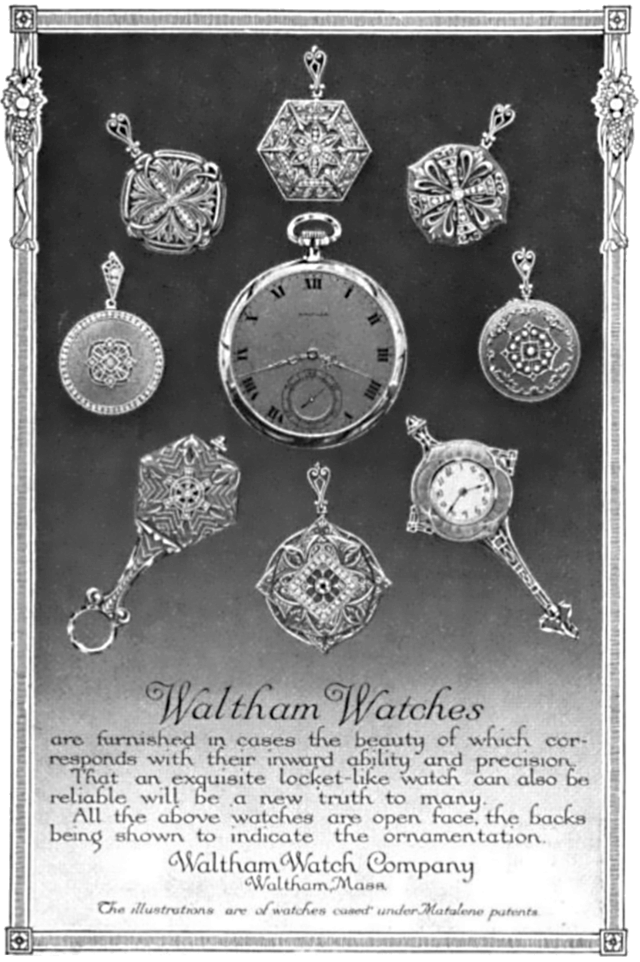

While plates were used to make geometric figures and to index minutes and seconds, figures were painted freehand. At this point in time, a worker averaged three painted dials daily, which saw the largest manufacturers, such as Waltham and, later, Elgin, employing more than 100 dial makers in their factories.

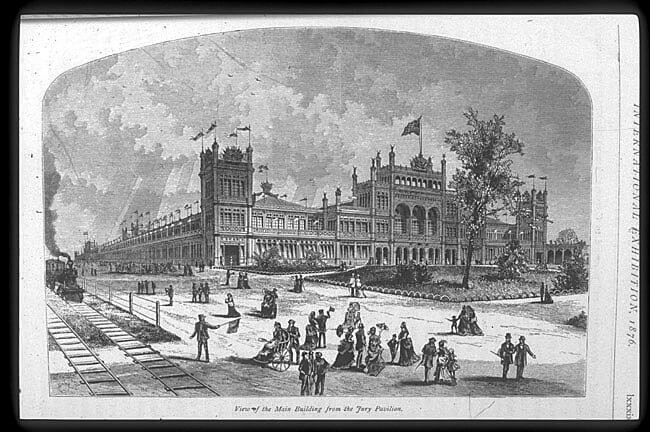

The Centennial Exposition

The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia was a distinct turning point in the way that the world viewed American watchmaking. On display there, among other things and alongside case makers Hagstoz & Thorpe, was an automated screw machine by Waltham.

A worker needed only to feed a spool of wire into one end of this machine to have a stream of perfect screws emerge from the other. This was the forerunner of the automated, computer-controlled long lathe widely in use today. And it won a gold medal at the exhibition.

Hello, hello

Putting this into context, consider that this was the same exhibition that first displayed Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone.

At the same time, it should also be acknowledged that some American watchmakers were particularly proud of the finishing and decoration of their movements, and more often than not these were beautiful in places that no owner ever came to see, though the main aim of the era was good precision and reliability at a low cost.

Innovative American manufacturers actually had special machines to manufacture almost every part of a watch faster, more accurately, and with less labor involved than anywhere else. And these American machine-manufactured watches’ rate results actually rivaled those of the Switzerland’s handmade timepieces.

Swiss watchmaking prevailed – contrary to English watchmaking – because Swiss watchmakers studied American production methods and adapted them to create higher-end, mass-produced movements that decimated the English horologists, who continued to produce timepieces by their traditional method of one piece at a time.

The Swiss offered both their usual handmade wares alongside lower priced, machine-made timepieces that were often characterized by the wonderful design that Swiss watchmakers continue to be so famous for.

Continued tradition

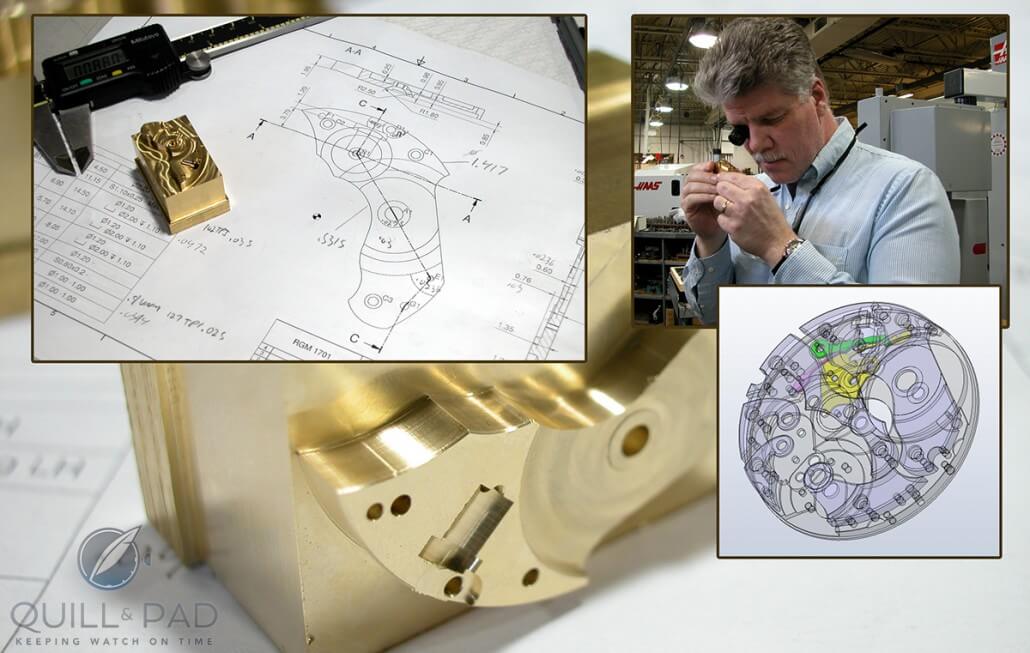

Serial watchmaking in the U.S.A. more or less died out in 1971 when Hamilton was sold to the Swiss (it is now owned by the Swatch Group) and its production moved to Switzerland, However, the last decade or so has seen a rise in American watchmakers once again, even if they are greatly helped out by European suppliers.

The revival was definitively spearheaded by RGM and Kobold, and now Shinola (with quartz movements) has set up production in Detroit.

With its enormous marketing and financial resources, lower-priced Shinola is directing attention to not only the Motor City, but the entire “Made in America” movement across a variety of product categories.

The U.S. can now even boast classic independent watchmakers, with Keaton Myrick perhaps heading the pack.

Myrick was trained at the Lititz Watch Technicum, after which he earned WOSTEP and AWCI certification. After working at Rolex USA’s service center, he opened his own restoration shop in Oregon.

And he makes his own watches by hand, one at a time. Though I have not yet had the honor of speaking to him yet myself, I had the unique opportunity to thoroughly examine one of his watches thanks to Tim Jackson of IndependentInTime.com and learn more.

According to Jackson, Myrick makes about 85 percent of the movement himself. He also makes his own case and dials. Each watch – he only makes a maximum of three pieces per year – is fully customizable as it is made to customer specifications.

To learn more about American watchmaking during the Industrial Revolution, we recommended reading:

Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] You may also like Made In America: Not Only On Independence Day. […]

[…] over to Quill & Pad to read the full […]

[…] For more about the roots of watchmaking in the U.S.A., please read Made in America, Not Only on Independence Day. […]

[…] For more about the roots of watchmaking in the U.S.A., please read Made in America, Not Only on Independence Day. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!