It’s a story that could have come out of a thriller novel, and it’s about one of the oldest known watches in the world, which has is thought to have been made in 1505 by Peter Henlein. .

This is not the famed Nuremberg Egg (Nürnberger Ei) that was previously thought to be Henlein’s first confirmed work. This watch I am talking about here has been dubbed the Pomander Watch (Bisamapfeluhr) and it was confirmed as the oldest known watch at a press conference that took place on December 2 in Nuremberg, Germany.

The committee included Hermann Grieb (of Grieb & Benzinger, most likely the foremost vintage watch expert in Germany); Dr. Peter Mikitisin, physicist, appraiser and specialist for industrial computer tomography; Frank Fox, expert for micro and macro photography; and Dr. Georg von Tardy, horological specialist for metallurgy and metal processing.

The intricately engraved and decorated case of Peter Henlein’s Pomander Watch (credit: www.peterhenlein.de)

This apple-shaped watch (or small portable clock) first surfaced in 1987 thanks to a watchmaker apprentice, who found it at a London flea market in a box filled with spare parts and metal bits. He had bought the entire box full of items for 10 pounds and only discovered the unusual timepiece among the objects later.

In 2002 he sold it. After a specialist for renaissance timepieces declared it a forgery or a copy of the original, the next owner sold it too. The nagging question of its authenticity remained with its latest (anonymous) owner, though, causing him to engage in further research.

And it was a good thing, too: as it turns out, he was in possession of what may be one of the world’s earliest known portable timepieces.

The evidence

The shape of the case was attributed to Henlein through documentation of previous work. The copper and gold plating of the case was examined using a laser micro spectral analysis, which provided the time period.

Inside the case under the dial an engraving was found displaying the letters M, D, V, P, H, N. This has been interpreted as “1505” (MDV in Roman numerals) and “Peter Henlein Nürnberg” (PHN).

As Peter Henlein, who was born between 1480 and 1485 in Nuremberg, had not yet become a master locksmith (watchmakers did not officially exist yet), the formal guild rules of the time forbid him to sign any work he did. Therefore, he apparently hid his signatures.

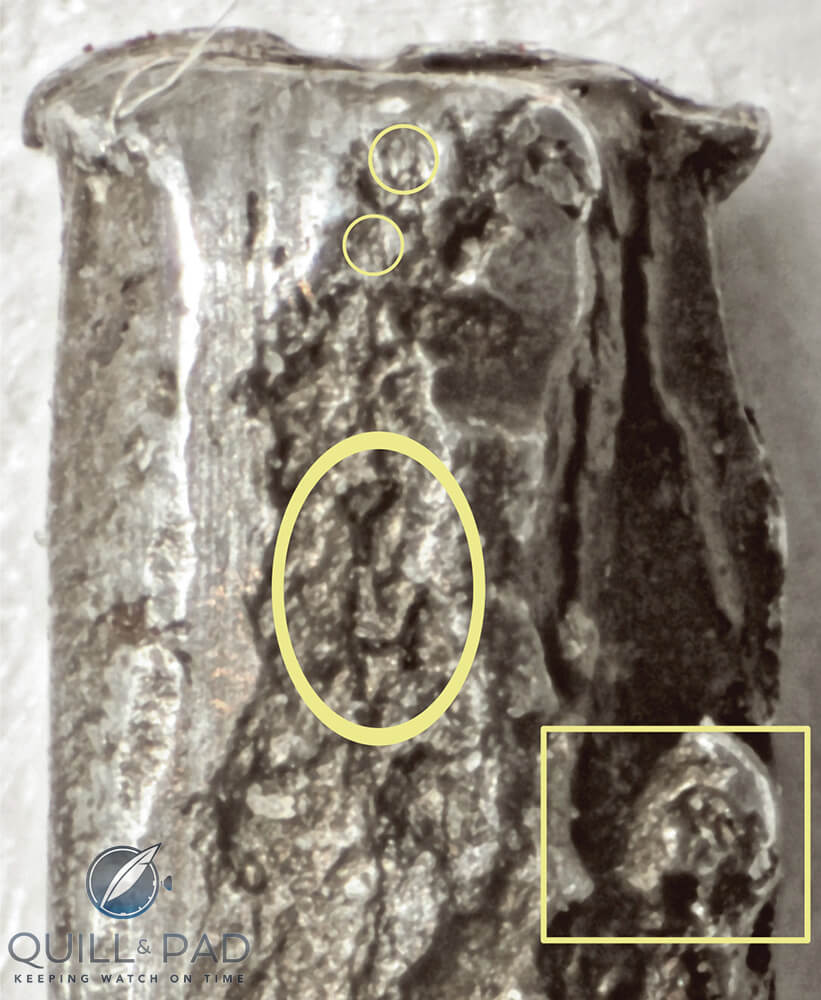

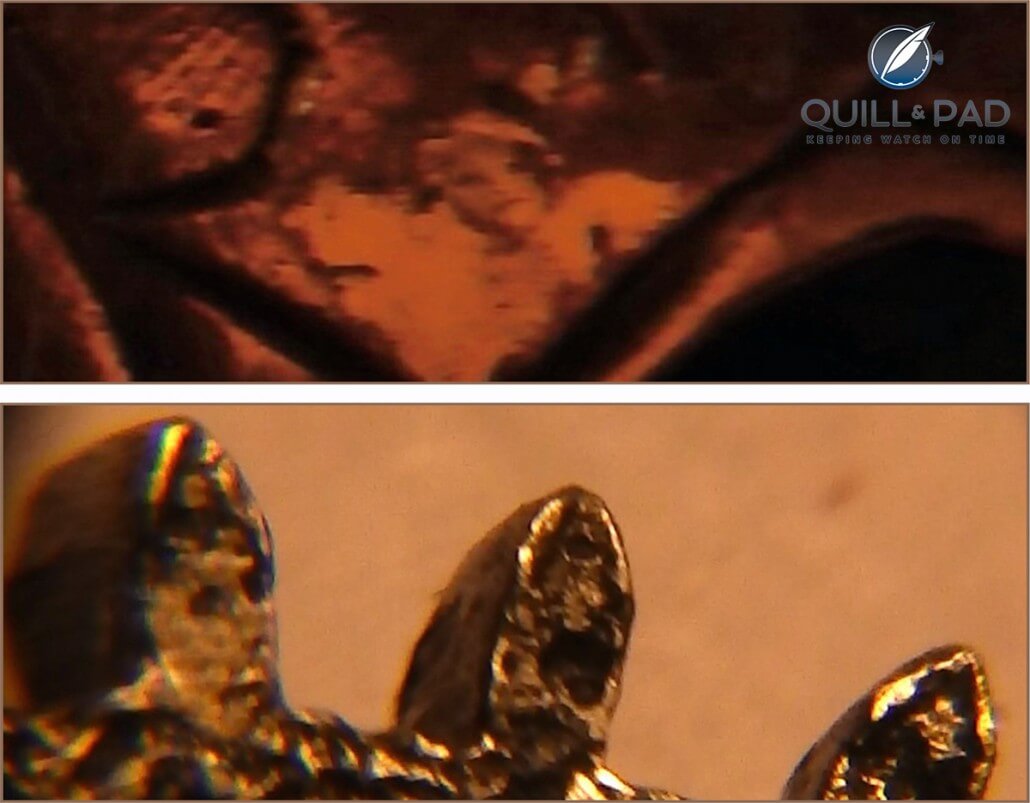

And this leads us to one of the most important points of the findings: the inner case had been fire-silvered. Underneath the layer of silver, the researchers found microscopic “PH” signatures, which could not be recognized with the naked eye. However, they almost form a background pattern on all components of the watch

The research examinations of the individual elements have led the researchers to believe this Pomander Watch was also most likely Henlein’s personal watch.

Grieb explains his findings

This video below (unfortunately only in German) of a news report by a local television station in Düsseldorf, Germany, shows Hermann Grieb inspecting the individual parts of the watch. He expresses his feelings that this watch is the real thing.

Grieb and other experts have even found a microscopic engraving of the initials PH on the back of the single hand. While some may argue that the engravings would be too small for someone to have achieved in the early 1500s, it is perhaps important to point out that master engraver Albrecht Dürer also lived in Nuremberg at the same time. He might have been able to show others some features of his own artisanal work that would make this possible.

Microscopic initials “PH” of the watch’s creator Peter Henlein and little faces engraved on the Pomander Watch (credit: www.peterhenlein.de)

For the moment, this priceless artifact remains in a bank safety deposit box, but its future location is slightly unsure. It may go up for auction.

While Grieb thinks that a price cannot be put on this timepiece, others estimate its current value between 30 and 50 million euros. Should it go to auction, it will certainly set new records.

It should be noted that there are still many who find the results inconclusive and continue to debate as to the creator of the Pomander Watch (Bisamapfeluhr).

*This article was edited on December 23, 2014 to better reflect the ongoing discussion.

Quick Facts The Pomander Watch by Peter Henlein, 1505

Case: copper, gold-plated on the outside, silver-plated on the inside, 45 mm in diameter, 38.5 grams in weight, three feet on the bottom

Movement: 36 mm in diameter, 54.1 grams in weight, iron, hour wheel with four teeth, upper plate skeletonized, chain and fusée, regulating arm with holes for 2 hog’s hairs, approx. 12-hour power reserve

Function: hour shown by one hand

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] Pomander Watch (Bisamapfeluhr in German) is believed to be the oldest known watch in the world. Following an in […]

-

[…] analysis indicated the period of the (making of the) material, which should be around 1500. Read this article for more detailed information about the research of the aforementioned […]

-

[…] The story about the Pomander Watch is that it was found at a London flea market, in a box filled with spare parts and metal bits, and bought for 10 pounds. After that is was sold a couple of times. And there were doubts; was this a copy of an original or not? Laser micro spectral analysis indicated the period of the (making of the) material, which should be around 1500. Read this article for more detailed information about the research of the aforementioned committee: http://quillandpad.com/2014/12/15/the-worlds-oldest-watch-a-peter-henlein-mystery-from-1505-solved/. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Thank you for the good and interesting article! It is time that the truth about the myth of Peter Henlein to the daylight.

Ein Mythos auf dem Prüfstand…..

thats crazy

Hi guys –um, all due respect but this makes no sense. We are asked to believe that in 1505 an early watchmaker signed his work, with dozens of microscopic signatures, invisible to the naked eye, when there was no optical technology that would have even let him see what was doing, and that he did so apparently at random over a plethora of otherwise rough surfaces? And that whoever did so had the superhuman control and eyesight necessary to make micro signatures but at the same time chose to leave the decorative engraving on the case as (relatively) crude as it is? Really? This doesn’t look like even remotely convincing evidence, it looks like someone is indulging themselves in an exercise in wishful thinking. The fact that the story ends in speculation about the millions of euros this watch is supposed to be worth doesn’t inspire confidence either. If these experts are in possession of better evidence I’d love to hear it but this just looks like completely unsubstantiated speculation to me (in both senses of the word.)

Hi, Jack, and thank you for sharing your experience with us here. Regarding the initials, I have no idea how they were made but given the sheer number of them, I would imagine that the easiest would be to engrave the tiny initials just once on the head of a punch and simply tap it all over.

On one hand we have a committee composed of:

1. Hermann Grieb: A foremost vintage watch expert in Germany.

2. Peter Mikitisin: A physicist and appraiser.

3. Geirg von Tardy. A metallurgy specialist who dated the metals used on the watch.

These three men have handled the watch, have examined and analyzed the watch in microscopic detail, and they have been confident enough of their findings that they put their reputations on the line and held a press conference.

On the other hand you:

1. Have no particular experience (relative to the committee) in very old German timepieces.

2. Haven’t handled the watch in question, let alone examined it is any detail.

Based on their careful examination, the committee validated the watch as by Peter Henlein and dated as 1505.

There has been no polemic in Germany to date from watchmakers, journalists and vintage collectors surrounding regarding the conclusions of this report, which was more widely reported there than elsewhere.

There are those that doubt even the most factual of evidence and I’m all for health skepticism,but there appears to be a fairly strong consensus that the watch is by Peter Henlein, dated 1505.

We will certainly publish an update if more evidence (for or against) comes to light.

HELO Sir i have really old and antique piece of old skeleton pocket watch the watch have no name just there is photo of guru nanak sb and photo is made of really expensive stones and in dial there is no number 12 and in place of number 12 the j is write which sho its brand name help me to find the brand of the watch

i also sell this watch this is so old look like 1600 ancient time watch

Eyeglasses, the magnifying glass, and simple microscopes were around in the 13th century, some 150 years before this watch was made, so the technology did exist. In circa 163 BC, the Chinese were using microscopes made of lenses and a tube filled with water.

Hi Ian, thanks for the reply. If you note, in no way do I claim expertise in antiquarian German horology however I think you’ll agree that I’m not totally unfamiliar with watches and watchmaking either. In any case that’s not germane to my skepticism. You suggest that these marks that are supposed to be signatures might have been made by a punch. Naturally this raises the question of why on Earth the maker would have troubled to do so. If you examine your story, you will see that for that scenario to obtain, it would have been necessary for the maker to make a couple of dozen, individual, micron scale punches (one assumes, in his copious spare time) as the signatures are all sorts of different sizes and no two sets of the alleged letters are alike. Anything is possible but I submit to you that no reasonable person would find this plausible. Why would Henlein do such a thing? Had he nothing better to do with his superhuman vision and motor control? Was it, perhaps, the first of April?

Against this bit of speculation –which I am very comfortable characterizing as “totally implausible” –we have the possibility that these are simply random irregularities in the surface of the metal and that the, in many cases very slight, resemblance to lettering is coincidental. Occam’s razor is not infallible but here the cut it makes is very clear. And the “little faces” are merely risible.

If one is in possession of conclusive evidence that represents a major discovery in one’s field –even in one as obscure as antiquarian horology –there are accepted norms for presenting it; one publishes one’s evidence in a peer reviewed journal or three. There will always be those who are prepared to substitute fantasy and wishful thinking for convincing, clearly disclosed evidence, but I see no evidence of consensus on the attribution of this watch to Henlein in any meaningful sense at all. (And as I am sure the owner and three gentlemen who made the evaluation know, it is extremely difficult to make a definitive attribution of such an ancient, unsigned watch in any case.) A comparison to Henlein’s known work would be nice but there is none –the Melacthon watch linked to in the story has no maker’s mark and while there is no reason to say Henlein did _not_ make it there is likewise no reason whatsoever to assign it to him, certainly not definitively.

The metallurgical evidence is not presented; reasonable objections about provenance of the watch are not addressed; the institutional and commercial affiliations of the presenting committee are unclear; their competence to discuss this evidence objectively and from a foundation of experience on _their_ part in antiquarian watchmaking is not revealed, and on and on. What we have instead is implausible non-proof the acceptance of which requires a positively superhuman suspension of disbelief. If I am wrong, I will happily and publicly eat my words but as it stands, the alleged evidence is so paper flimsy that to call it so, is to do a gross injustice to the robustness of paper relative to the (alleged) evidence. I have no axe to grind here at all, it is just that as presented thus far I can see little reason to accept the assertion that this is a signed watch by Peter Henlein from 1505, much less his “personal watch” –other than the one you have made, which is an argument from authority, a well known logical fallacy.

But hey, I could be wrong. God knows it happens!

I did note that Jack, which is why – having no particular knowledge of the subject either – I’m on the side of those with the most expertise.

As a metallurgist and a hobbyist watchmaker, i spend most of my time restoring early British, French and Swiss watches. While none quite as old as the subject watch, i worked on 4 watches from mid to late 1600 and mostly early to late 1700s, and i have to concede that watchmakers from that time have demonstrated a unique ability to leave their mark. I have seen everything from a biblical reference all the way to profanity and pokes at the royals of the era. most common is just initials of the makers, some very small in size. However…

Even if we take it at face value that PH made a punch and did in fact stamp his initials all over the place, and the metal property of work hardening under the letters as they are punched, in turn allowing the letters to leave a visible trace as metal erodes… these parts are eroded so far, that there is no way we should be able to see the initials. not to mention that there is absolutely no reason to stamp dozens of initials all over same part. If punch was used, he would have to have a set of at least 5 of them, i counted at least 5 different letter sizes… One of the bigger ones is plausible, but not the rest. If the “experts” claim all are initials, i have to question their credibility. Thats all i have to say about the evidence.

Other than the above evidence, i am optimistic that the watch is genuine, pitting on the metal looks right, as well as very well made parts, obviously hand made. make me thing the movement is genuine, with the possibility that the case was made later, or the crude engraving was made later… If it is a forgery, it was done by an extremely talented person, probably with access to the original piece.

He was practicing. Roger Bacon was making lenses in the 13th C, it’s possible watchmakers in the 16th were improving on that, and if this was his own watch, it may have been an experimental one. It’s a theory.

I will have to agree with Jack on this one. I have no expertise in anything to do with watches or history of this period, but it stands to reason why would the maker back then punch signatures in the watch and little faces,if no-one, even the maker, cannot see them and be certain it worked out. Even bigger question WHY?

This doest make no sense Ian. Will the details of the findings be published by the “Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chronometrie”?

Leaving aside the idea of “signatures” too small to be seen with the optics of the time, being “Found” on a rough surface by people who were being paid to find them, and who were not being paid to consider Apophenia.

Any modern watchmaker knows that a balance spring is vital to well regulated time, and early descriptions of this watch note the maker’s clever use of a boar’s bristle as a crude hairspring. This despite that fact that balance springs were not introduced until roughly a hundred and fifty years later. Neither any of Henlein’s other (later) watches, nor any contemporary clocks or watches have balance springs (until Hooke and Huygens 150 years later) suggesting that this cannot be anything but a later forgery (perhaps constructed from period-correct materials) by someone with a knowledge of watchmaking, but not a knowledge of history.

What do hairsprings have to do with this watch? Boar’s bristle regulators are not uncommon in early watches. Having an admittedly crude regulator doesn’t preclude its alleged age.

As a retired engineer I find the above remarks fascinating. My first comment is that science is so far advanced now and nothing is impossible.

My second is that the Germans have always been super engineers. The best automotive engineers make the best cars now.

I for myself collect American Railroad Watches but having a limited budget precludes me from getting more. I find the experts comments wonderful

I’m curious. Another watch attributed to Henlein and dated AFTER the watch in this story is drum-shaped and much simpler. Why would he have gone from elaborate and more complex to simpler? Seems the drum-shaped watch would have come first.

Looking at the script above, how can it be as the first coil spring was invented in the 1760s. As far as I know watches work on a coil spring

Mainsprings/coil springs appeared in clocks in Europe in the 15th century. The steel that they were made with was untempered, and they distributed power unevenly so that clocks had to be wound more than once a day. Peter Henlein worked with mainsprings and created small clocks/watches that ran for almost 2 days.

The entire thing sounds like a made up story, absolute bunk