Interconnectivity And Independence: The McGonigle Tuscar

There exists in the modern world an idea that many believe they understand, but few really do. We understand this idea as a concept, and the majority of people might claim some form of it for themselves, though in reality it is usually quite the opposite.

In fact, because of the interconnectivity of the era in which we live, I think this word has actually lost much of its original meaning and is offered more for its feel than for the connotation it implies.

What is this idea, this word that has become a placeholder for something else? It’s “Independent.”

The first time many are exposed to this idea is when they are taught about independence in school, such as when America declared independence from England, or when King Henry VIII declared independence for the Church of England from the Holy Roman Catholic Church.

The origin of the word independent lies somewhere in the early seventeenth century and originally meant “not subject to control by others.” Not surprisingly, the word actually sprang from religious organizations wanting autonomy from larger church organizations.

This led to the general concept of “independent” being considered the freedom to choose for oneself. And while this still holds true, and many billions of people around the globe share this condition, in most cases it is an illusion.

The reality is that because of how societies work, communities function, and economies create goods, almost no one is independent. At least not completely. I may be independent of my parents to make decisions about whom I marry and where I live, and I may be independent of my government about what I think and what issues I care about, but that is likely to be where my independence ends.

I am dependent on a million different industries to simply do any activity I do every day, and a billion different people who put their efforts into creating those industries. I do almost nothing independently and all by my lonesome. That is just the world we live in, and it’s pretty awesome.

ENIAC was an early-generation computer, so despite its size, was relatively simple by today’s standards; that doesn’t mean it would be easy to make one, though

I don’t have to know how to build a computer, but I get to use one. In fact, no single person actually knows how to build a computer. That is if you consider they would first need to know how to fabricate all the required components, and before that create the raw materials for said components, and even before that, know how to find and extract those materials from the earth.

And even before all that, they would need to know what materials would be useful for computer components, and how to build machinery to extract those materials, and how to make the raw materials to build those machines and on and on. You see, nothing we ever do is truly independent; it relies on the entirety of human experience and knowledge.

Even creative thought.

Nothing is created in a vacuum, and as such no new idea could come from a person born into and never knowing anything other than an empty white box. A person needs a frame of reference to create anything, which is what makes creativity so amazing. Because it was all there waiting to be created, waiting to be thought of in just that way so that it could then inspire another new thought.

It is in this complete and utter interdependence that we find the soul of independence. Those that are not told what to think and what to build, or why to build something because a focus group liked blue and preferred rounded edges over chamfers.

The world of the independent watchmaker

This is the how independent watchmakers arise. They see what has come and what has been done. They understand references from their childhoods as much as they see technical details. They hold proudly their life experiences and personal tastes just as much as their professional accomplishments.

A pair of such watchmakers are the brothers John and Stephen McGonigle from Athlone, Ireland, and a fine example of their independent spirit lies in the Tuscar timepiece.

Independent watchmakers have career accomplishments just like watchmakers for large brands, training passed down from previous generations, and modern equipment that has been continuously improved upon by countless engineers and craftsman.

They did not pull this stuff out of a hat or wish it into existence with fairy dust; it exists from the help of others thanks to the interconnectivity of the world in which we live. But what the McGonigle brothers have on top of all that are their independent thoughts, free from corporate red tape and yearly line refreshes.

The Tuscar is a great example of this, not to mention a great example of the McGonigles’ background and heritage with the added details in every “corner” of the watch.

Begin with the crown, the first way you’ll interact with the watch, and you’ll notice it isn’t any normal shape but instead asymmetrical and marked by characters from the Ogham alphabet, an early medieval alphabet that formed the basis of the early Irish language.

Those apparently random notches on the McGonigle Tuscar crown (right side) are letters from the old-Irish Ogham alphabet

Pretty clear where this inspiration came from, but to use it on the crown is a very clever way to incorporate heritage into a component that many may simply overlook. Certainly, few consumers see the crown as a way to add character besides with a nice little logo engraved into it. The McGonigle brothers think differently.

The devil in the details

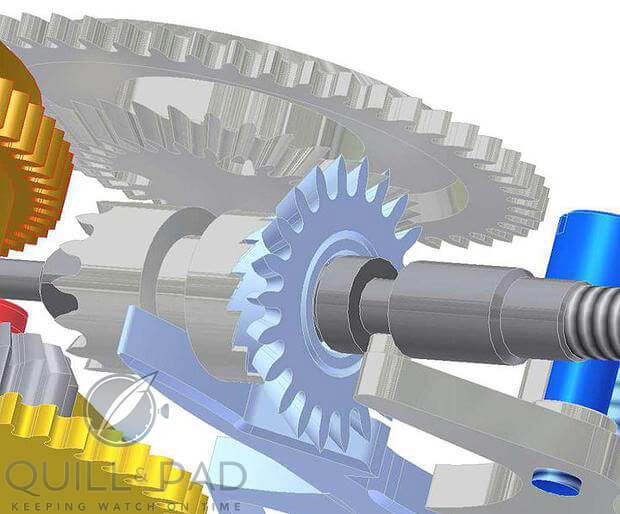

It doesn’t stop there; moving inward just a few millimeters, the winding stem reaches the keyless works and a conical winding gear. Not seen in more than a select few pieces, a conical winding gear provides a much more direct and smooth connection to the two mainspring barrels by meshing at a right angle via two 45-degree gears instead of two roughly meshing straight gears.

Also, right next to these is a set of finely finished (and highlighted thanks to a skeleton dial) cam and clutch levers and a lever spring, all of which allows you to change between winding and setting when the crown is pulled. These are usually hidden and given very little treatment, but the McGonigles gave them special attention so they fit with the design of the dial components.

Not too shabby, and we haven’t even reached the meat of the movement!

The entire gear train begins with two mainspring barrels operating in parallel, offering a hefty ninety-hour power reserve, and continues on toward the escapement, all gold-treated.

The two spring barrels of the McGonigle Tuscar are clearly visible at 11 o’clock and 1 o’clock through the transparent sapphire dial of the “One in Ten” pre-series Tuscar (sold out)

Along the way, hours, minutes, and seconds tick off, with the display of seconds awarded its own half-subdial with a twin-tipped second hand. The markers are on two concentric half-tracks and the second hand points to the outer and inner track respectively on its circular journey.

The hour and minute hands comprise finely polished steel with grained gold tips attached, both of which have micro-bevels on them. Next is the rather large 12.8 millimeter free-sprung balance wheel with eight large adjustable counterweights and Breguet overcoil hairspring. All of this is held in place by a very mean-looking German silver bridge.

In fact, all the bridges are cut from German silver, lending a warmer hue to the movement than most coated or plated examples. Everything is finely beveled, polished, and circular grained with polished countersinks and enough depth that old Stonehenge would be jolly well jealous.

There is a clear sapphire dial, beautifully shaped, sitting over the top half of the movement of the Tuscar One in Ten, with the numbers 9 through 3 pad-printed along with the McGonigle logo. This ensures you can see all the hard work and creativity that went into the movement underneath.

That movement is the first in-house example for the McGonigle brothers, and its creation came about with the help and expertise of technical designer Alberto Papi.

And from the rear

If you flip over that movement, and by extension the entire watch, to see the other side, you are in for simple and clean perfection. A large, (almost) three-quarter plate makes up the base plate for the movement, thereby supplying a canvas for clean countersinks and circular graining as well as hand-engraved, hand-inked details stating the name of the piece and where it was made (hint: it says “Tuscar” and “Ireland”).

There is also an awesome little spring and click for the mainsprings and a second plate holding the second half of the winding mechanism.

Then there is the “eye” that showcases the balance wheel from the underside in a fitting window to the soul of the Tuscar.

Actually, the soul of the Tuscar resides within the McGonigle brothers and their hometown of Athlone, Ireland. The design and feel of this piece is entirely Emerald Isle, if I do say so.

The strong case and design elements mixed with the soft warmth of the German silver combined with the authenticity of independent creativity is wondertacular!

It’s nice to see that this second piece is such a resounding success after the huge splash made with the debut tourbillon. I am on the edge of my seat to see where the brothers go next. With their combined history and success, my fingers are crossed for a fun complication and original style.

Hopefully it’s not too long to wait, because I really need my fingers to type this! Oh well, how about a breakdown!

• Wowza Factor * 9.7 In-house, independent movement in German silver and depth to die for from the land of saints and scholars, so yeah.

• Late Night Lust Appeal * 98.76 » 968.504m/s2 Like few other pieces, the history behind this piece goes back millennia, and the design is awesomely unique.

• M.G.R. * 70.4 Broke the 70* mark, must be a pretty geeky movement for me! Conical gears and the simple perfection of a time-only movement sometimes must be honored.

• Added-Functionitis * N/A Like many before it and undoubtedly many after it, this piece has but one function: to tell the time. Because of that you can skip the Gotta-HAVE-That cream for the still-amazing non-swelling. Whoa, déjà vu.

• Ouch Outline * 12.1 – Cracking A Tooth On A Piece Of Aunt Marge’s Fruitcake It doesn’t matter what time of year it is, there is probably an ignored fruitcake lying around. So be careful when you (God knows why) take a bite of it. Though I’ll raise my hand to the task if it wins me a Tuscar!

• Mermaid Moment * Less Than Thirty Seconds A double half small seconds track makes me giddy and ready for the rehearsal dinner!

• Awesome Total * 1152 Multiply the ninety-hour power reserve by the 12.8 mm balance wheel and you have a monstrously awesome total. Worth it!

For more information, please visit www.mcGonigle.ie.

Quick Facts

Case: 43 mm, 18-karat white and rose gold

Movement: manual winding Caliber McG01

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds

Price: 52,800 Swiss francs

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] For more on the McGonigle Tuscar and the true meaning of independence in watchmaking as personified by the McGonigles, see Interconnectivity And Independence: The McGonigle Tuscar. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!