Salvete and blessed day, my good sirs and gentle ladies! It is I, Benedict Aragorn Philippe, Marquis of West Wolverhampton, third son of the Duke of Birminghamshire, and personal horological advisor to the crowned king, William the Sneezy. While I and my associates have, at the very least, grand estates to our title, only a select few have been honored to inherit a sprawling palace of regal stature.

My father, the Duke of Birminghamshire, (Did I mention I am the heir apparent? Rock on, primogeniture!) is one such privileged nobleman, and as such I feel my time spent as a youth within the halls of such grandiose architecture has granted me the ability to proffer my thoughts and musings concerning these physical bastions of aristocracy.

Palaces are the most important dwellings of noble and royal families as they are visible extensions of the power of our ruling class. This means that palaces should be presented as pinnacles of achievement, adorned in the most classic of styles emanating from ancient Greece and Rome. It is also acceptable that there be influences from previous celebrated rulers such as Louis XV.

Wherever the noble class has taken a grand departure and incorporated designs from most recent history is where the tradition we have taken so long to craft is most utterly abandoned. It is almost as if the new nobility cares not for our stringent adherence to tradition and instead wishes to “shake the horse carriage” with newfangled styles.

I give you a noted example: the Palace created in the name of Jean Dunand (known artist) by two horological disruptors from the families Claret (Christophe, first son of Lord Donnelly Claret of Rouen) and Oulevay (Thierry, first son of Archduke Pierre Hasselhoff Oulevay II).

The Palace of Jean Dunand does not fit the noble definition of a palace as it draws almost entirely from the decidedly modern Victorian structural expressionist style that is currently sweeping the continent.

It besmirches its palatial forbears with Art Deco-style design that pushes well past the boundaries of tradition we have worked hard to maintain.

It is truly hard to be noble these days, if only the plebians could ever understand the struggle.

Seriously, bro?

No, not really. It’s just me, the resident nerdwriter, Joshua. But I had you going, didn’t I? What do you mean you knew it was me the whole time? Oh, well.

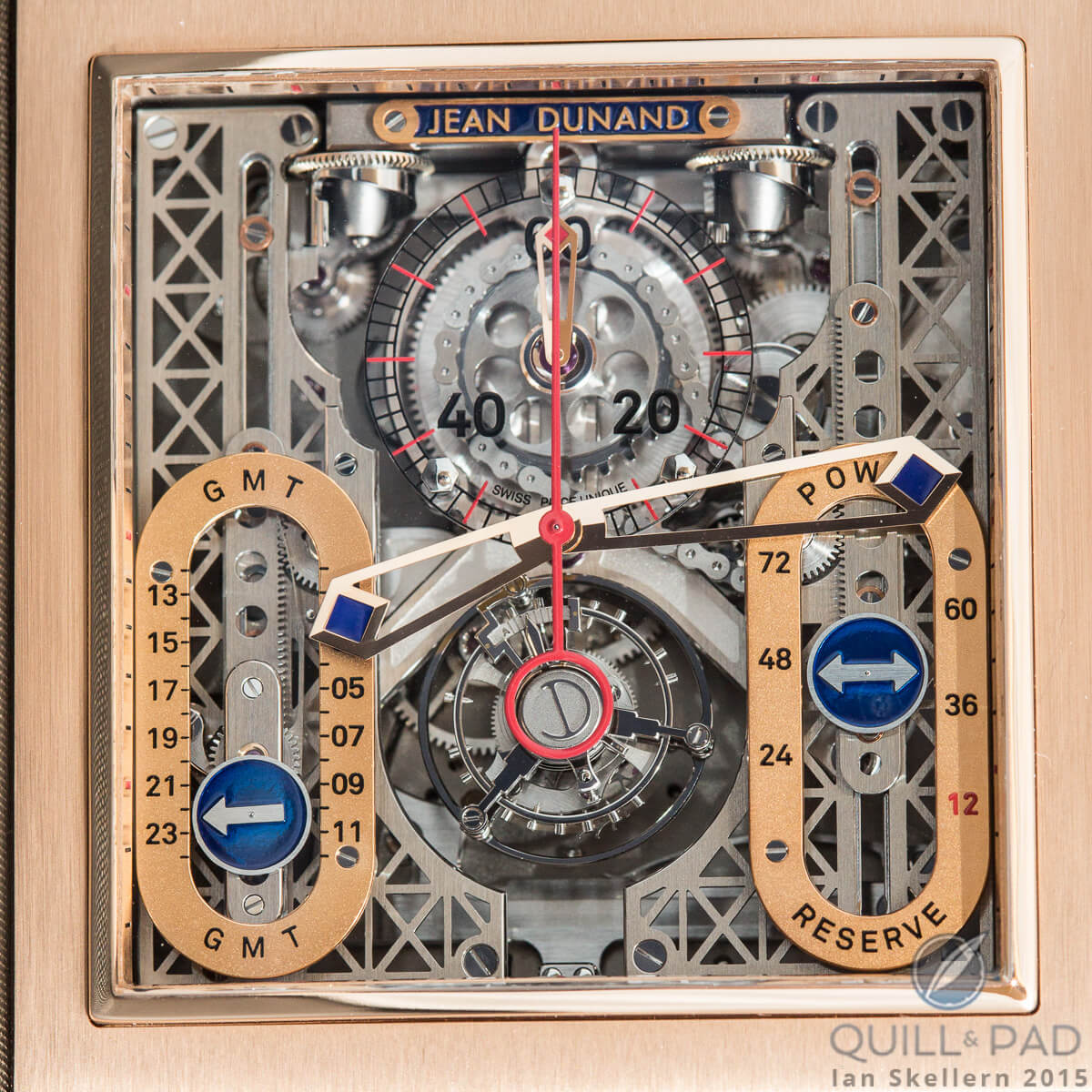

Regardless of my failed ruse, the assessment is spot on. Palaces by definition are usually very traditional, very ornate, and very large. The Palace by Jean Dunand has two of those three descriptives going for it – its size and the fact that it is very ornate.

But its design and inspiration are anything but horologically traditional. It is modern, it is complicated, and it is very unique.

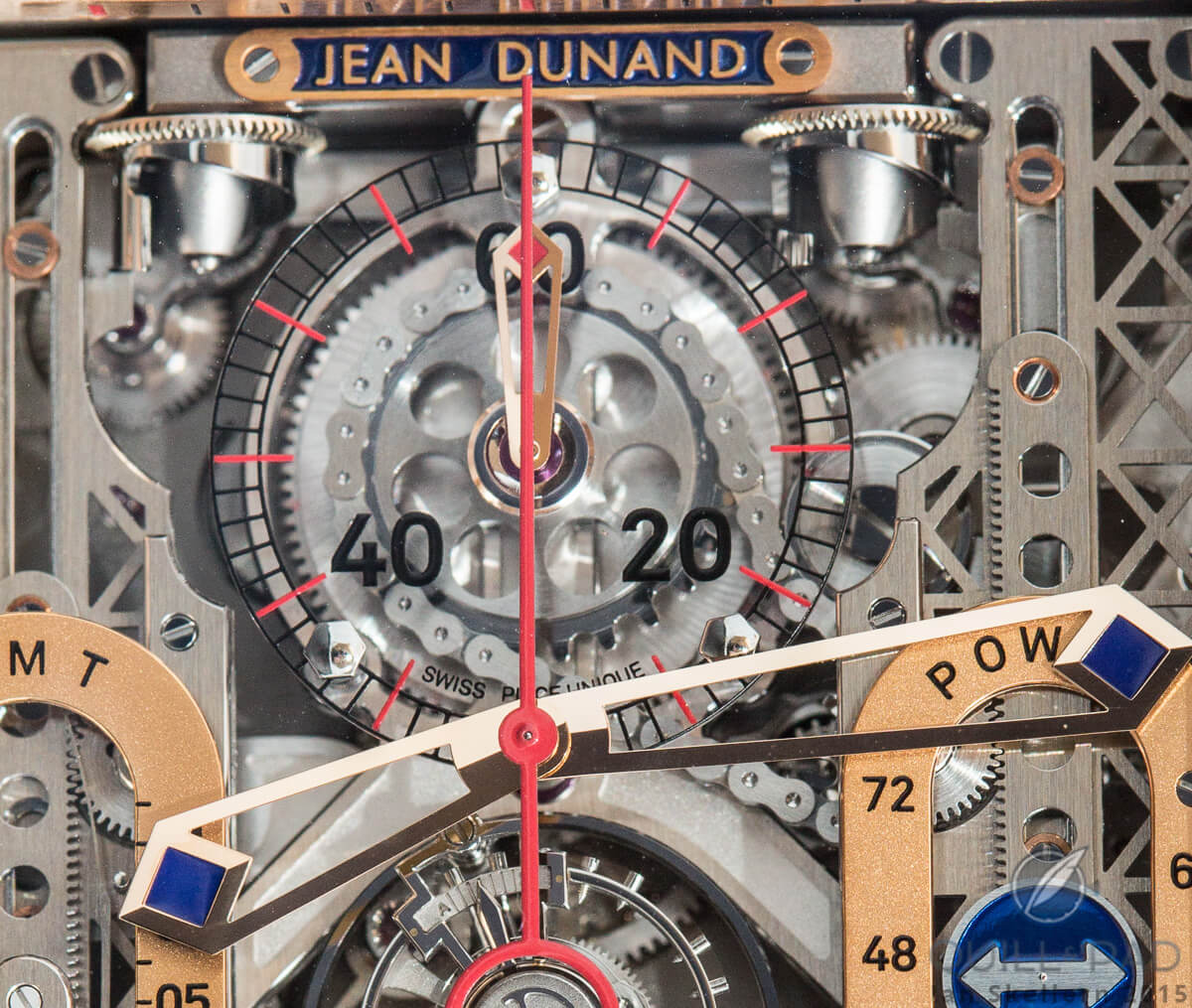

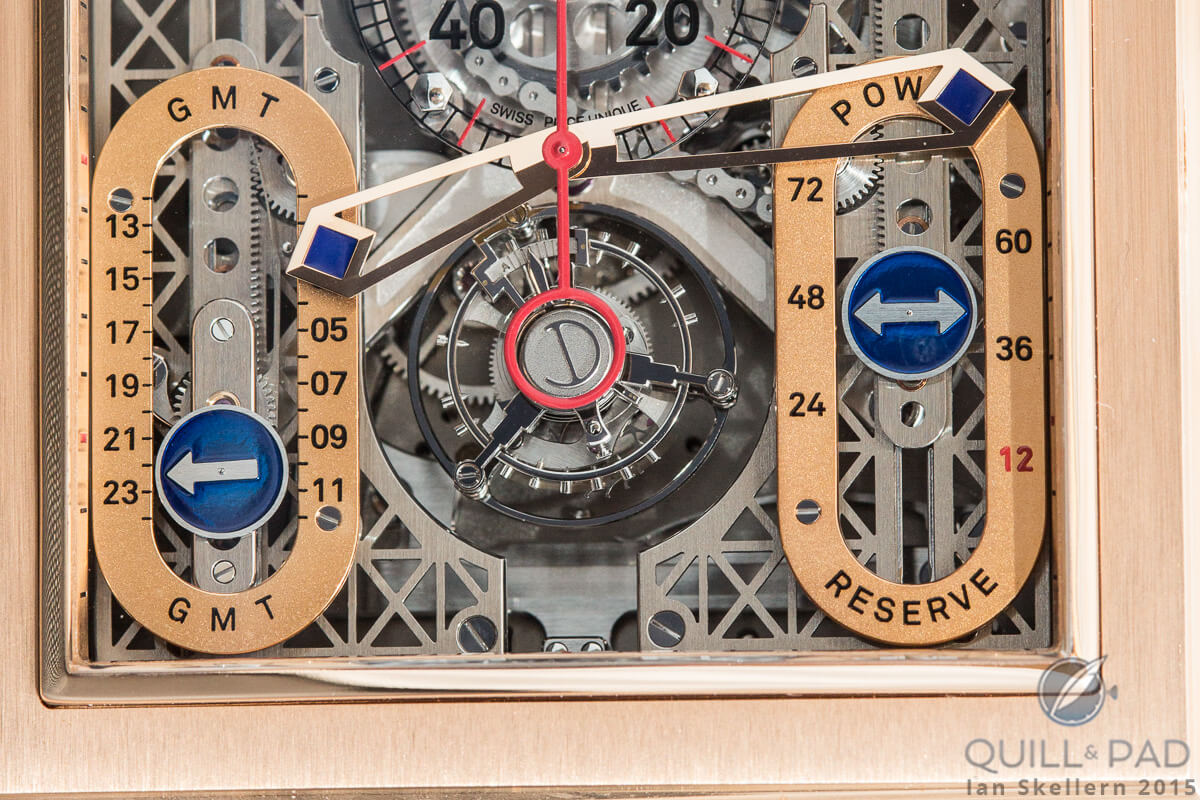

Even though this wristwatch is already a few years old at the time of writing, it still holds the title of unique for the following reasons: first and foremost are the two linear displays for the second time zone (GMT) and power reserve indication. Power reserve displays have been displayed linearly before, so this is nothing new. But a GMT with daily double retrograde action in a linear format? Now, that is something new.

While the 72-hour power reserve slowly winds down in one direction, the GMT indicator repeats its path twice a day on the other.

When the linear slide returns to its top position after twelve hours, an attached arrow (modeled on old elevator floor indicators) flips 180 degrees to point to the opposite side of the scale from where it started. The display indicates hours 1-12 on the right and 13-24 on the left. This should be more than exemplary on its own, but none of that takes into account how the darn thing moves. I have three awesome words about that: three-dimensional cam.

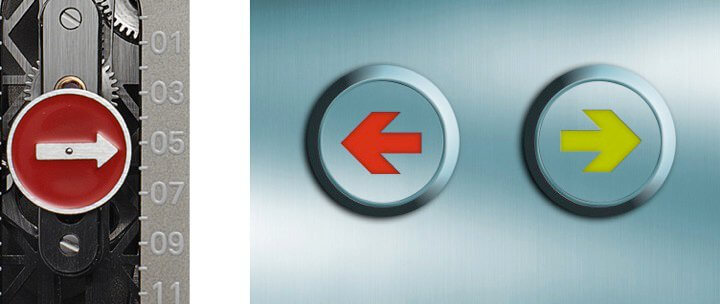

The arrow indicators on the Jean Dunand Palace were inspired by elevator floor displays seen in Art Deco hotels

Not so easy

These cams are not simply flat, oblong discs; they are miniature roller coasters attached to bevel gears. A tube that has the cam profile cut perpendicular to its axis of rotation is attached to (or machined as part of) two bevel gears that mesh with the movement gear train. They receive horizontal rotational motion that is translated to “vertical” rotational motion.

That change allows the cams to push levers in a linear fashion, instead of a somewhat circular motion, to meet up with the slide mechanisms. The levers give a slight mechanical multiplication to the distance the cams move, allowing for the full range of movement the sliders are looking for, probably similar to a rack and pinion system.

This required some very careful planning and (I’m sure) some very tedious adjustment and readjustment to get the linear slide to move the appropriate amount of distance with the corresponding movement of the three-dimensional cams. The 90-degree bevel-gear hollow cam wheels allow for an entirely new display of GMT time and power reserve, simultaneously allowing for other possible indications in the future. Plus, the addition of the GMT quick change button on the bottom of the case adds another layer of complexity to an already complex mechanism.

The chain that drives the power reserve indicator coming from the gear under the 60-minute chronograph counter; note the exquisitely crafted hour and minute hands on the Jean Dunand Palace

If that was all that this watch had to offer, it would still be pretty fantastic, but we are just getting started. The winding mechanism is a bit unorthodox, and if anything harks back to tradition more than other elements since the mechanism consists of a miniature chain. Connected from the keyless works to the barrel, the chain provides a flexible connection with the mainspring.

This, in a rare circumstance, could have an added side bonus of partially protecting the mainspring and its meshing teeth from becoming stripped or broken, which would create the problem of not being able to wind the mainspring, a problem that is likely familiar to vintage watch owners.

More and more

Beside that, it really just looks cool. Yeah, that is my objective assessment.

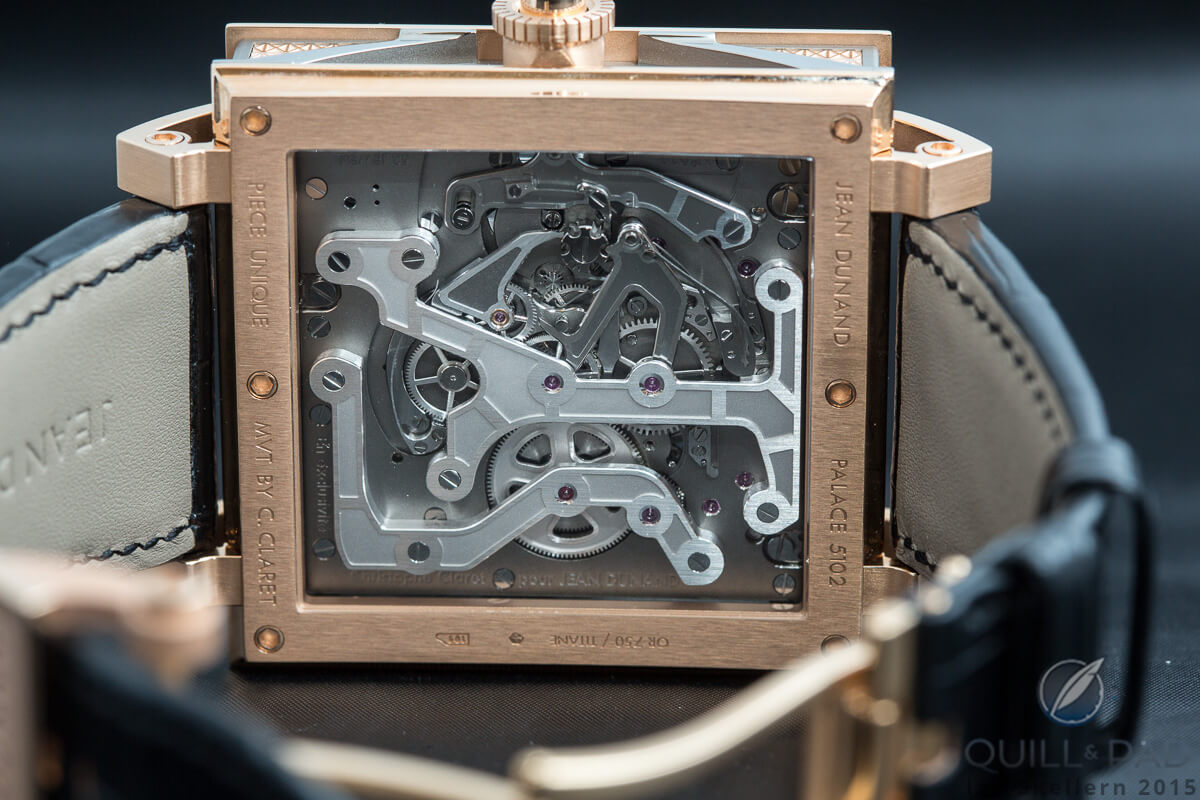

In all seriousness, though, the incredibleness keeps on going. The movement is a monopusher chronograph with a sixty-minute counter located just below 12 o’clock and a sweep chronograph second hand. The details of the chronograph part of the movement are clearly displayed via the caseback, and I do mean clearly. The layout of the movement is unlike anything I have seen before.

While the wheels for the chronograph are spaced rather traditionally, the bridges and levers are anything but. Surprisingly, they are designed in an almost electrical circuit-board style with square linear bridges with “contacts” around screw bosses. This is probably one of the better movements to look at while trying to understand the motion and interaction of chronograph gear trains.

But that has to be it in the movement department, right? Nope, for good measure (and because he can), Claret decided to add in a flying tourbillon on the dial side, which, thanks to its one-minute period of rotation, also acts as a seconds indicator.

It’s got the looks, too

Phew, that’s a pretty serious movement, interesting in every respect. So interesting is the movement, in fact, that it would be hard to create a design for the case and dial elements that live up to this movement. But that is covered. Since Jean Dunand is inspired by Art Deco, Art Nouveau, skyscrapers, the industrial revolution, and the art of Jean Dunand himself, there was plenty to draw from.

The case looks like an amalgamation of the Crystal Palace of London and Paris’ Eiffel Tower with numerous other references added in specific areas. The case utilizes side windows, hollow arched lugs, intricate micro lattice structures, sharp angles mixed with symmetrical curves, and even miniature pillars and name plaques creating the sense that this could have very well been crafted between the years 1880 and 1930.

It really just fits.

The bridges on the back of the Jean Dunand Palace are inspired by the steam locomotives from the golden age of engineering and Art Deco 1880-1930

The only thing that seems sort of out of place is the movement design from the rear, but some could argue that it resembles basic electrical circuit designs, which would have been widely used by the end of that time period. However, it was indeed designed to resemble steam locomotives from the golden age of engineering.

It all fits, making for a Palace that might not live up to what old Benedict Aragorn Philippe, Marquis of West Wolverhampton, might have believed to be correct in terms of architectural direction for a traditional palace, but it definitely lives up to its inspiration.

While not a production piece or even a proper limited edition, the Jean Dunand Palace definitely deserves to be recognized and discussed. There are many cool things happening right now in horology, and new things that I am excited to discuss in the future. Sometimes, however, we must look to yesterday (however near or far that day is) to be recharged for the possibilities the world offers.

And with that I return to the Nerdwriter Quotient. In case you don’t remember, this takes into account impressive facts about a piece and divides them to obtain one single, rounded number. Any Nerdwriter Quotient is incomparable to another Nerdwriter Quotient, yet stands as a signifying condensation of beauty, engineering, and fantasticism. It will be designated by the Greek letter Ξ.

The calculation goes as follows: Number of movement components (703) ÷ case thickness in mm (16) ÷ number of known examples (2).

Nerdwriter Quotient of the Jean Dunand Palace:

- 703 ÷ 16 ÷ 2 = 22Ξ

For more information, please visit www. jeandunand.com.

Quick Facts

Case: 48.2 x 49.9 x 16.65 mm, titanium with white gold or red gold

Movement: manually wound Caliber CLA 02CMP

Functions: hours, minutes, retrograde linear slide GMT, monopusher chronograph, linear slide power reserve

Limited: a handful of unique pieces

Price: $417,000

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!