Gerald Murphy (1888 – 1964) was born in Boston. His family owned the luxury goods retailer Mark Cross.

Murphy moved first to Paris and then the French Riviera in the early twentieth century with his wife, Sara Sherman Wiborg. The pair was famous for their hospitality and parties, which led to a vibrant and famous social life in the Roaring Twenties. Their circle of friends included a large number of artists and writers of the Lost Generation, which came of age during World War I.

Famous practitioners of arts from the Lost Generation movement included writers Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Franz Kafka, Henry Miller, Aldous Huxley, and painters Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso. In France, the grouping of artists was known as the Génération au Feu (“generation in flames”).

Most likely due to his flamboyant and creative social circle, Murphy was inspired to become a painter. His career was brief, but by all accounts significant.

The Murphys returned to the U.S. in 1934. At that time Gerald began running Mark Cross, performing duties as its president from 1934 to 1956 – after which he never painted again. It is believed that his return from Europe was precipitated by the fact that Mark Cross was on the brink of bankruptcy due to the Great Depression.

Mark Cross

Mark Cross was founded in Boston in 1845 as a purveyor of harnesses and carriage saddles (if this is sounding familiar, you can thank Hermès and Louis Vuitton) as Mark W. Cross & Co. When Patrick Murphy (Gerald’s father) acquired it following the eponymous founder’s death, it simply became “Mark Cross.” The company specialized in importing luxurious leather goods and other fineries like china and crystal from the old world to the new world.

Gerald Murphy sold it in 1961, three years before his death. It went under in the 1990s – only to experience the same fate that many old and well-respected companies do: resurrection. The resuscitated brand, in business since 2011, now specializes in luxurious leather and other types of high-end bags.

Eight years of painting

Gerald Murphy only painted from 1921 until 1929, and the works he created during this time were chiefly hard-edge still life paintings with abrupt transitions found between the color areas. His style was mainly Precisionist (the first American modern art movement; it celebrated the new American landscape and often featured industrial themes in a sharply defined manner) and Cubist (an early twentieth-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European art, particularly Parisian). Murphy and his contemporaries heralded the pop art movement.

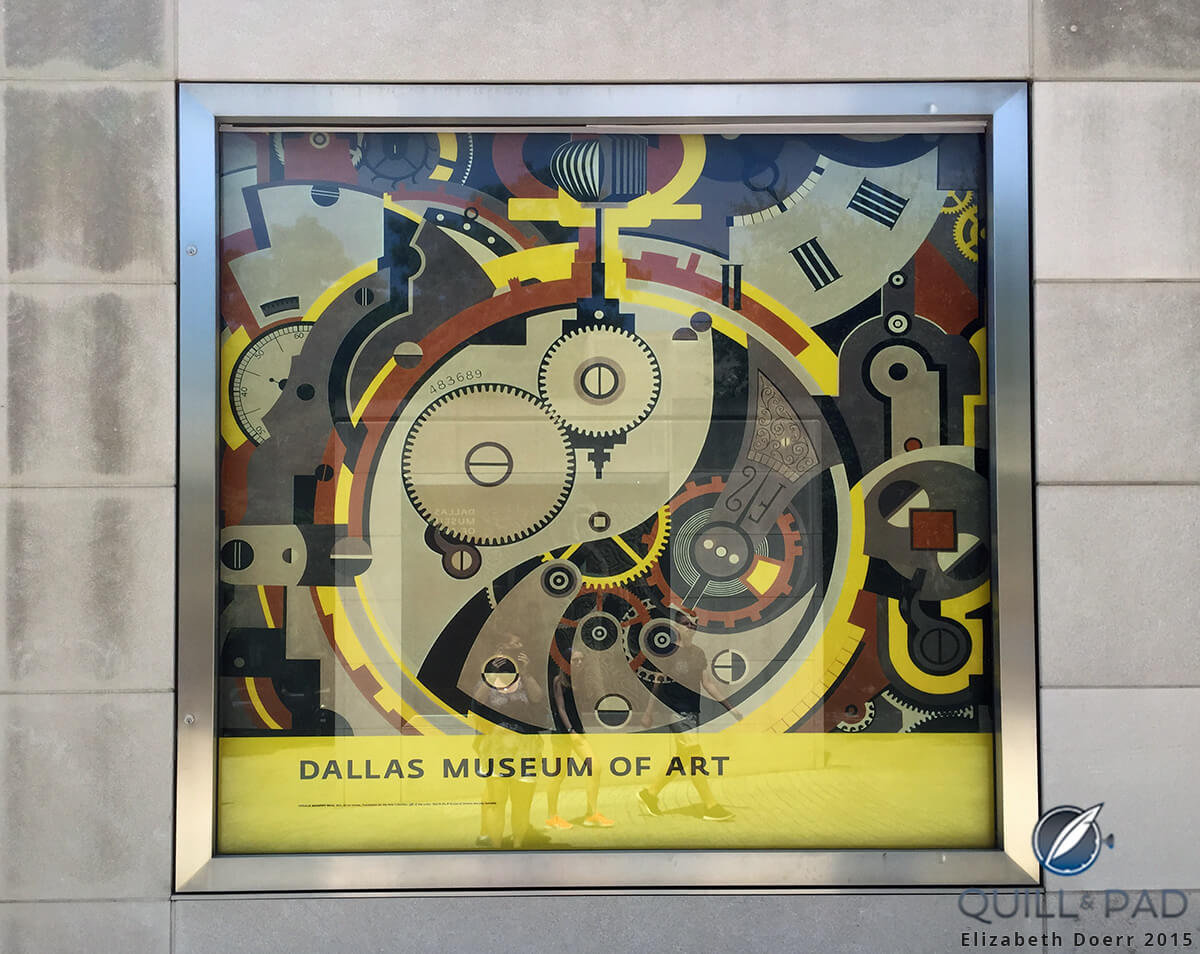

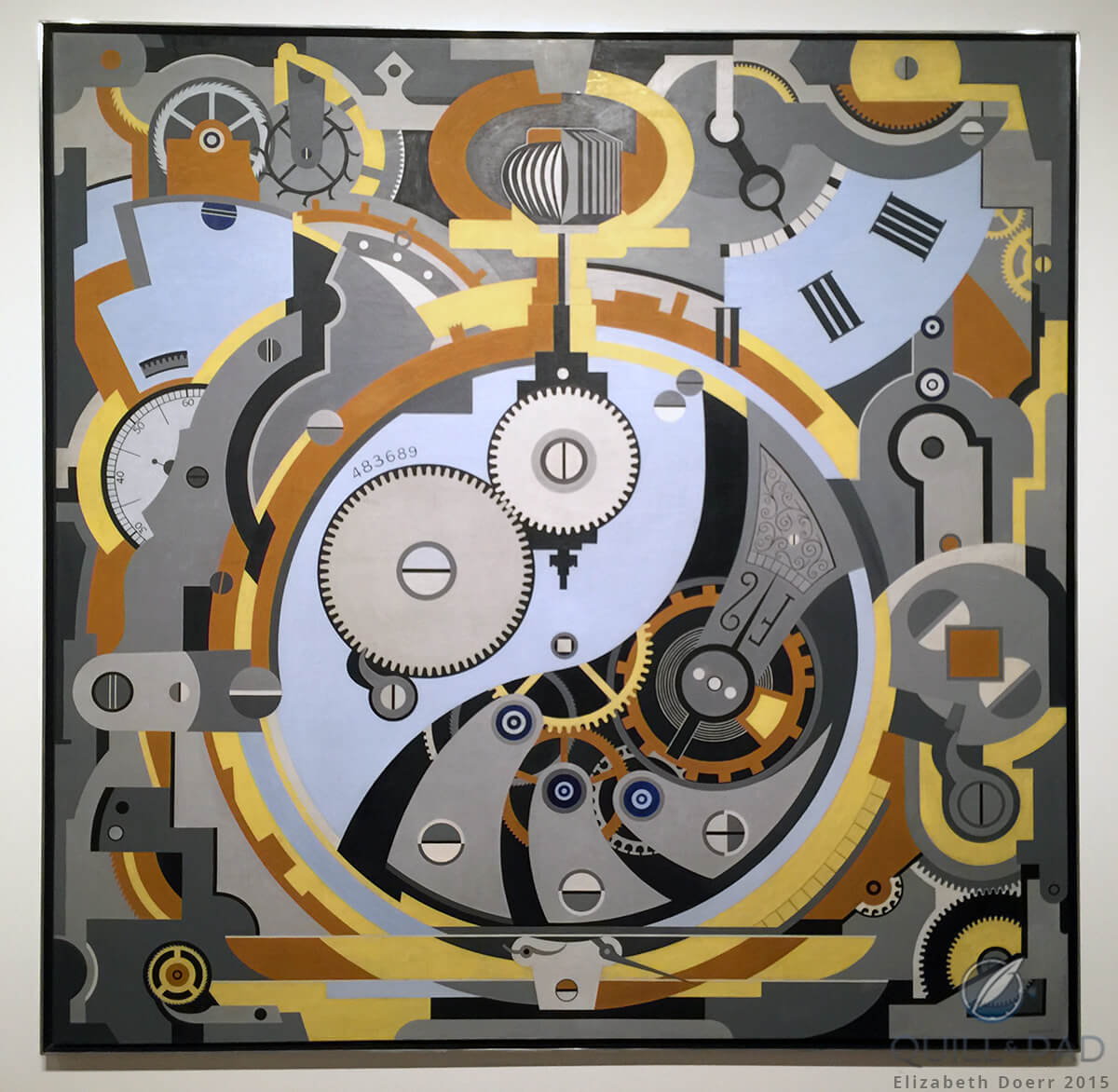

In 1925, Murphy painted the largest of his surviving works, an oil-on-canvas measuring 78 1/2 x 78 7/8 inches (1.99 x 2.343 m) simply entitled Watch. This painting – along with another called Razor from 1924 – are included as part of the Dallas Museum of Art’s permanent collection. They represent two of the eight works remaining from his 14-piece series.

The large, symbolic watch

This sizable painting was personally symbolic to Murphy. The mechanical components depicted originate in two different timepieces with biographical associations. One was a railroad watch said to have been designed by his family’s company, Mark Cross.

The other was a gold pocket watch that he apparently personally used, which was most likely far more luxurious than the Mark Cross. I deduce this by the split crown depicted at the top of the watch in the painting. The left side of the crown is oignon-shaped in fine Swiss tradition, while the right half is angular and machine-like, certainly less fine and more industrially American of the time.

Depicted here in the whole watch in the center of the painting is a fine screw balance, while the balance cock appears to be painted as engraved, which points to fine handwork.

According to vintage watch expert Jeffrey Hess of Hess Fine Art, the layout of the movement could be based upon a Rockford or a Longines pocket watch, or a combination of the two. This could indeed point to origins of both watches inspiring the painting: the Longines movement could be the one that powered the Mark Cross railroad watch.

Longines was known to have been the biggest maker of contract watches for American jewelers at the time.

The Rockford could have been the gold pocket watch he personally owned. Hess offers that, while a long shot, the serial number clearly visible in the painting could have belonged to a Rockford. If so, it represents one made in 1894.

But that is truly all conjecture. What is more important is the symbolic meaning of the painting to Murphy.

The combination of these two technical sources and their fragmentation across the large surface of the canvas testify to Murphy’s view of the ever-changing nature of time. He completed this painting in homage to Cubism, the prevalent artistic movement during his time. Cubism represents the dynamic act of seeing through a seemingly arbitrary collection of visual data from various perspectives.

Gerald Murphy gifted this painting to the Dallas Museum of Art’s Foundation for the Arts Collection, most likely in 1963.

It now permanently hangs in the Dallas Art Museum, where I spied it by chance on recent a personal visit to Dallas, Texas. It overwhelmed me, and I immediately wanted to know more about it. I’m glad I did.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] this article over at Quill & Pad, Elizabeth Doerr covers how she ran across this art in Dallas, and the […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

What a beautiful piece of art. I love the colours, size and pure subject as an enthusiast of timepieces and had also no idea of its existence. I enjoyed reading your article and now… wished there was a poster print available somewhere in the same size.

Me too, Ruurd! I’m glad you enjoyed this article – I was instantly captivated by this painting.

I cannot believe how captivating this painting is. I regret that I did not go to the museum in Dallas, I did not take it serious and neglected it. I should have…