by Ian Skellern

Amidst the turmoil of long days visiting brands at Baselworld 2016, a relatively early start on Thursday morning in honor of a press conference organized by the AHCI in collaboration with F.P. Journe brought a welcome change of pace.

The AHCI Young Talent Competition 2016 winners (L-R): Tristan Ledard, France, for clock displaying a linear equation of time; Anna-Rose Kirk, England for her Horizon Clock, and Anton Sukhanov from Russia for his Triple-Axis Tourbillon clock

The conference announced the winners of the 2016 Young Talent Competition sponsored by the AHCI, F.P. Journe, and Horotec. And the 2016 laureates are: Anton Sukhanov from Russia (who works with Konstantin Chaykin) for his Triple-Axis Tourbillon clock, Anna-Rose Kirk from England for her Horizon Clock, and Tristan Ledard from France for his clock displaying a linear equation of time.

But as well-deserving as the three winners are, this article is about one of the finalists that just missed out, Dilip Sivaraman, who made me wonder how on earth he had come to be there at all.

Dilip Sivaraman

Dilip Sivaraman is 38 years old (as of this writing in 2016), lives in Bangalore, India with his (luckily supportive) Catalonian wife Griselda, and is an architect by profession.

And that would have been that, except that two years ago, Sivaraman decided that he wanted to build a clock.

Now, as unusual as that may sound, quite a few watchmakers and amateur horologists actually do decide to build clocks.

Even if many who dream of building their own clocks have quite a bit of watchmaking experience and knowledge beforehand, they still rarely actually make anything.

Because making any type of working clock is very difficult; making a reliable and precise clock is exponentially more so.

Especially when it’s your first try.

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”I believe that every object has a soul, and that soul needs to be pure.” [/pullquote]

As Sivaraman explains, “I have loved mechanical horology for as long as I can remember. I believe that every object has a soul and that the soul needs to be pure. For instance, an analogue display should be powered by a mechanical movement: its soul would not be pure if the display was analogue but the movement was battery-powered. On the other hand, if a clock or watch does have an electronic movement, I would rather that it have an electronic display.”

“When I was 27 years old I got a raise and celebrated by buying my first mechanical watch, a manual winding HMT. HMT is one of many Indian watch companies that went bust during the quartz crisis and was rescued by the government (though has recently closed down). I bought the watch brand-new for around $7.

“I still wear that watch today.”

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”I celebrated by buying my first watch with my own money. And I still wear that watch today.”[/pullquote]

The beginning of Gato

While Sivaraman has had a lifelong interest in clocks and watches, like most of us he had never given even the slightest consideration to making a clock. That changed in 2014 when he bought an old pendulum clock.

He tried to fix the broken clock, but couldn’t. So he started reading and learning everything he could about clocks and was bitten by the bug.

“The love for horology was always there, but I had always considered myself a collector or even a connoisseur of timepieces; I had never considered ever making one. Then a couple of years ago, my interest in building my own clock was ignited by trying to repair an old clock,” says Sivaraman.

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”My interest in building my own clock was ignited by trying to repair an old clock.”[/pullquote]

Plan A

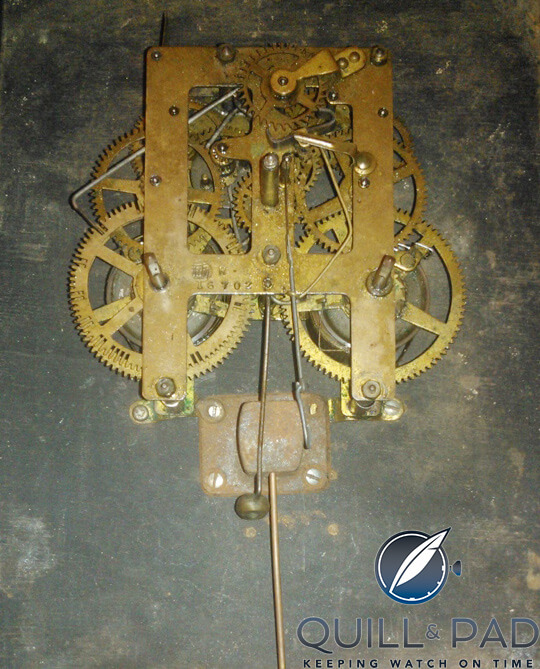

Sivaraman’s first idea was to design a new contemporary case for an old mechanical clock movement. Many of the mass-produced clocks in India from the 1970s didn’t look very good, and his plan was to buy one of these old clocks cheaply − perhaps too cheaply, as it turned out − and give it a new lease on life with a modern case.

He bought one of these clocks for around $30 from an antique dealer, but while it worked okay at the dealer’s place it stopped when he got it home and Sivaraman could not get it working again.

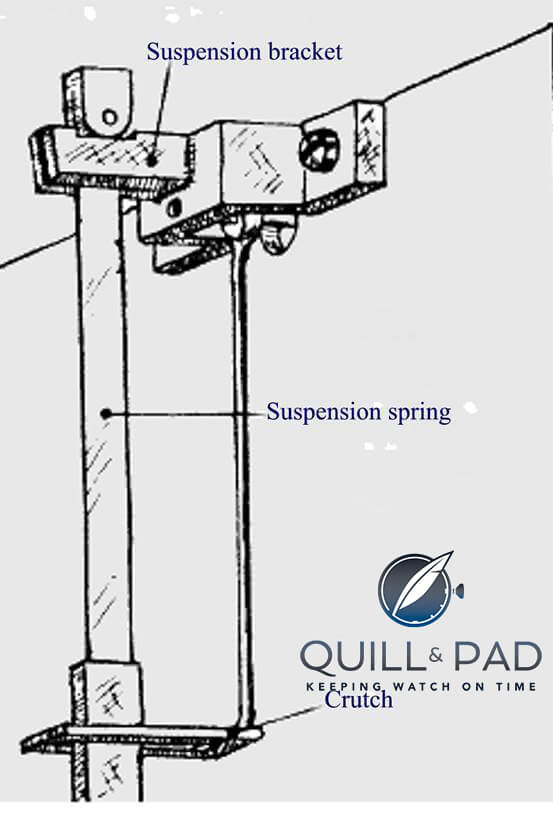

He then asked a local clock repairer to fix it. However, once again it would not work when he brought it home. So Sivaraman started to read what he could find about clock repair and deduced that the problem should be resolved by putting the clock in beat.

But that didn’t work. Then he read about bending the crutch rod to set it in beat. That didn’t work either. Then he started thinking about how, in any case, bending the crutch rod to make it work was a very clumsy and inelegant a solution.

So Sivaramann started learn how the crutches and beat-setting screw mechanisms worked in the world’s best clocks. And armed with more knowledge, he then realized that his old clock was far from being a perfect – or even a good – timepiece.

One thing led to another as it usually does, and Sivaramann decided that, as his old clock was full of flaws, he would make his own “perfect” clock.

This is the reason why Gato has such an elaborate beat-setting mechanism. And this is also the reason that the beat-setting mechanism is very conveniently positioned so that any layman can easily adjust the beat rate if required.

Sivaraman had learnt that the bent strip escapement in his old clock was a mainstay of inexpensive, mass-produced clocks. And that the movement plates, bridges, and wheels in his old clock were all much thinner than those on the best clocks, and that it had lantern-type pinions that, again, were not used in fine clocks.

And as Sivaraman explains, “I never did fix that old clock as from what I had learnt it was fundamentally flawed and I got really busy making my own ‘perfect’ clock.”

“However, that old clock, which still doesn’t work and has no dial, hangs in pride of place in my living room. That old clock is the reason that I found my calling. I will never dismantle it or throw it away; it will stay on my wall as a constant reminder of how my life has changed in the last couple of years.”

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”That old clock is the reason that I found my calling.”[/pullquote]

Thanks to his experience as an architect, learning new design software and drawing intricate technical plans was second nature to Sivaraman. He deliberately made plans for clock mechanisms without referring to existing models because he thought that this was the best way to learn. Sivaraman refers to his training as a “self-apprenticeship.”

But there is a big difference between designing a clock movement and making a clock movement: the former requires a computer while the latter requires tools, machines, and experience to be able to make high-precision components.

He had to learn how to both make high-precision components himself and be able to have pieces made to his specifications.

Despite having never used a lathe before, he bought an American Sherline 4500 and a drill press, after which he enrolled at a local technical college to learn how to use them.

After filling every spare nook and cranny at home with his new equipment and running out of space, Sivaraman rented a small workshop space close to home. He ordered books, joined online forums for help and advice, and learnt machining – all with the goal of creating his own clock.

And not just any clock, or as simple a clock as possible to start with, but as Sivaraman admits, “I wanted to create something that was unconventional.”

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”I wanted to create something that was unconventional.”[/pullquote]

The escapement

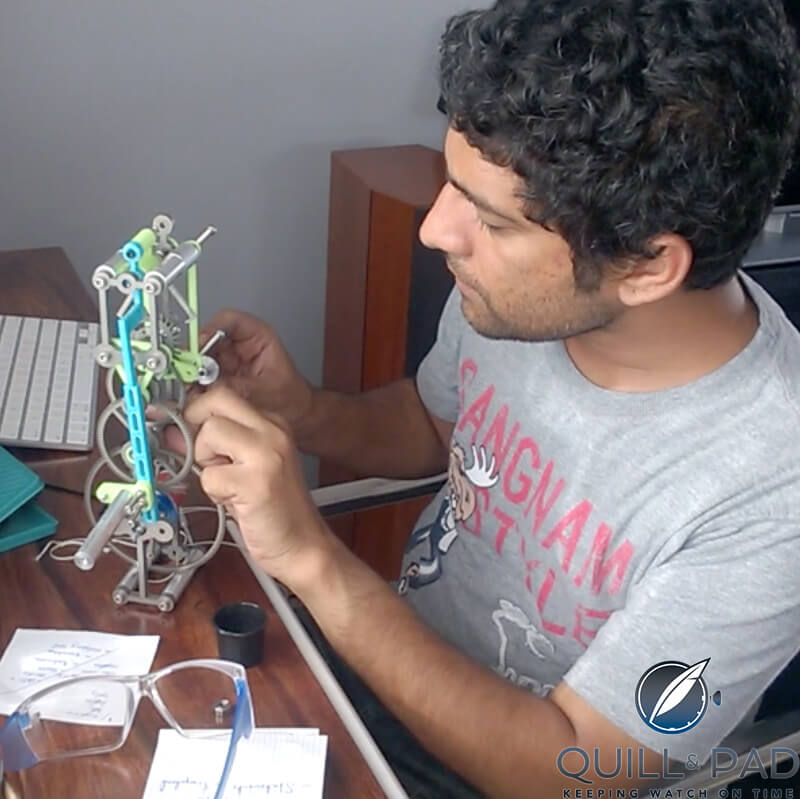

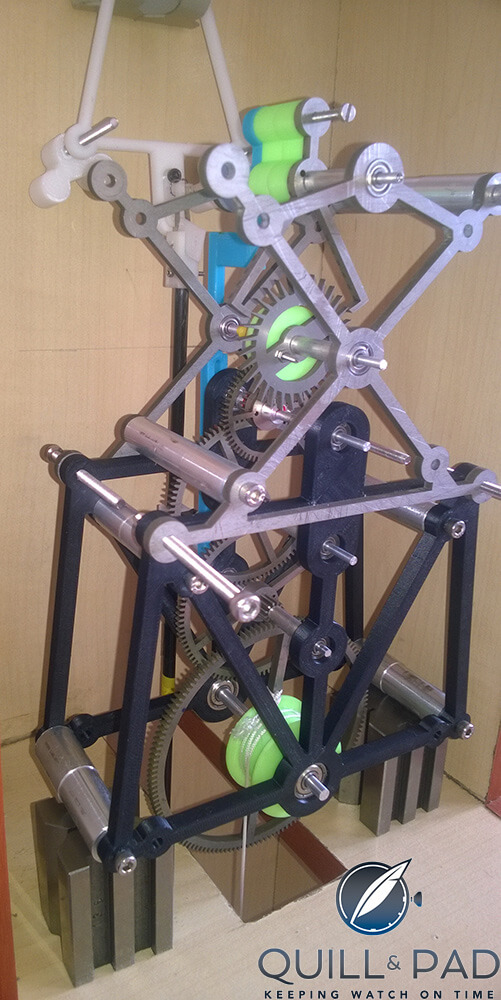

Jumping in at the deep end, Sivaraman decided that he should develop and make his own escapement, so he studied as much as he could about this most critical of components for any timekeeper. It took more than six months to realize, but it was a cause for celebration when he managed to make a regulator that worked perfectly.

He designed escapements and started out getting them 3D printed to begin to visualize how they worked. Sivaraman changed the anchor drop angle by half a degree one day, the thickness of the pallets another. He got new pallets and escapement parts 3D printed almost every other day until he felt that he had a good feel for geometry.

Not one to do anything by halves – including escapements – Sivaraman decided to make a (hopefully) functioning Graham deadbeat escapement on the 3D printer as a test. He then assembled and adjusted the escapement and attached a pendulum − this was just a stand-alone escapement, no movement.

His idea was that if he could get this deadbeat escapement model to work, then it would be just a matter of calculating gear ratios before starting to work in metal.

When this model escapement started ticking, Sivaraman knew he had had found his calling. He explains the emotion: “I felt how a parent would feel when they hear the heartbeat of their babies through an ultrasound machine for the first time. I really felt like a parent who had just had a baby.”

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”I really felt like a parent who had just had a baby.”[/pullquote]

Now that he felt comfortable with understanding escapements from making models, it was time to start machining parts in metal. After a lot more research, Sivaraman narrowed down his steel alloys down to stainless steel 316 and 440, then placed an order on eBay for silver steel (also known as Sheffield steel) rods to make his arbors.

Sivaraman had his gears and wheels made by EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining), also known as spark erosion, because of the precision available with that method.

Gato

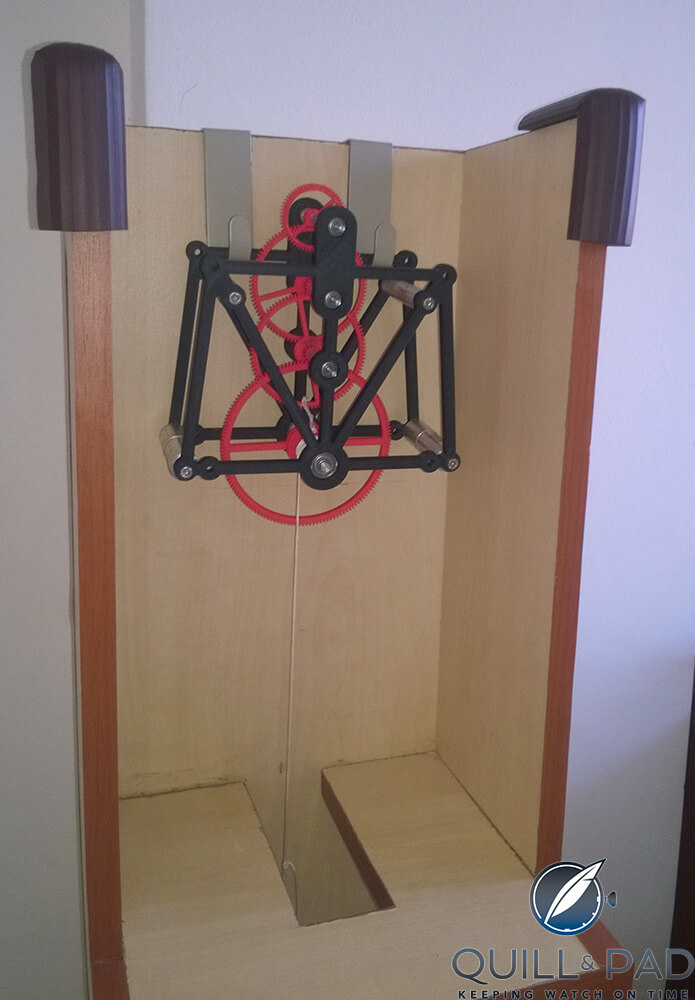

First things first: why the name Gato? The main attribute guiding Sivaraman throughout the development of Gato is that he wanted above all reliability and longevity for the clock. Astute readers might remember that Sivaraman’s wife is Spanish, and gato is Spanish for cat; a cat has nine lives.

Sivaraman is quietly confident that, “Gato should last for at least nine generations; each new generation of owners will give it a new life to keep it ticking.”

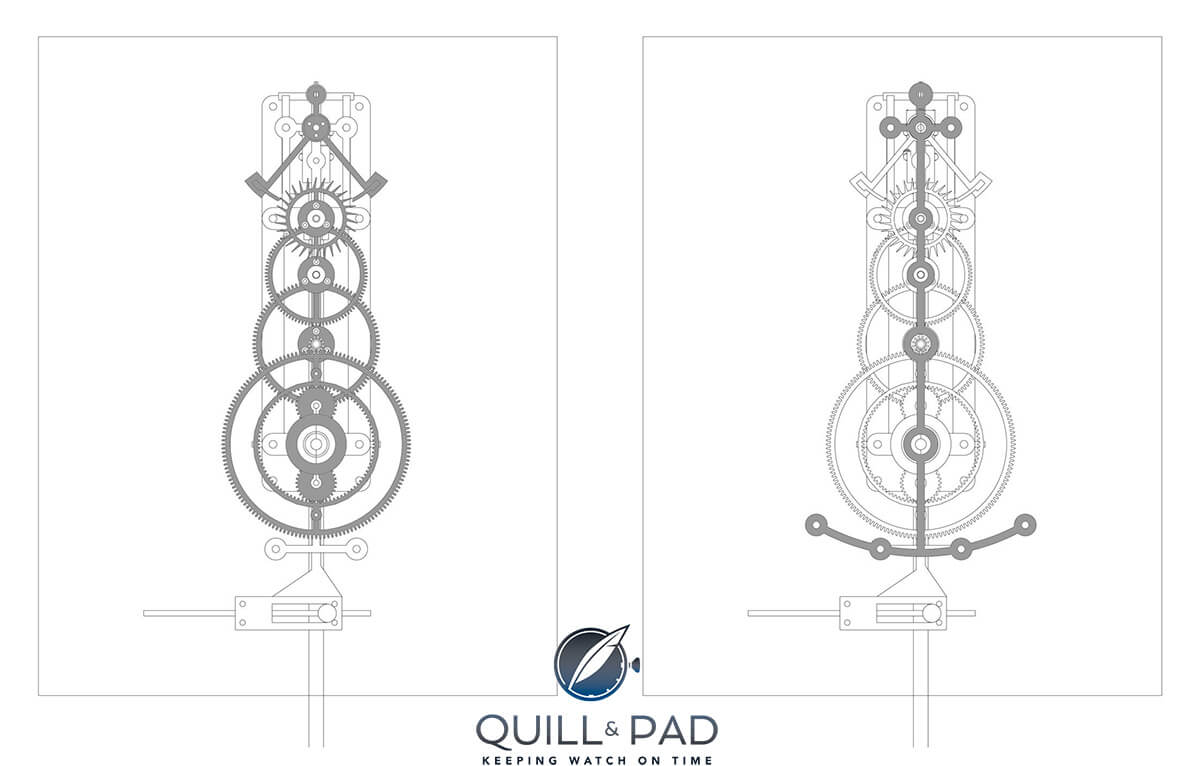

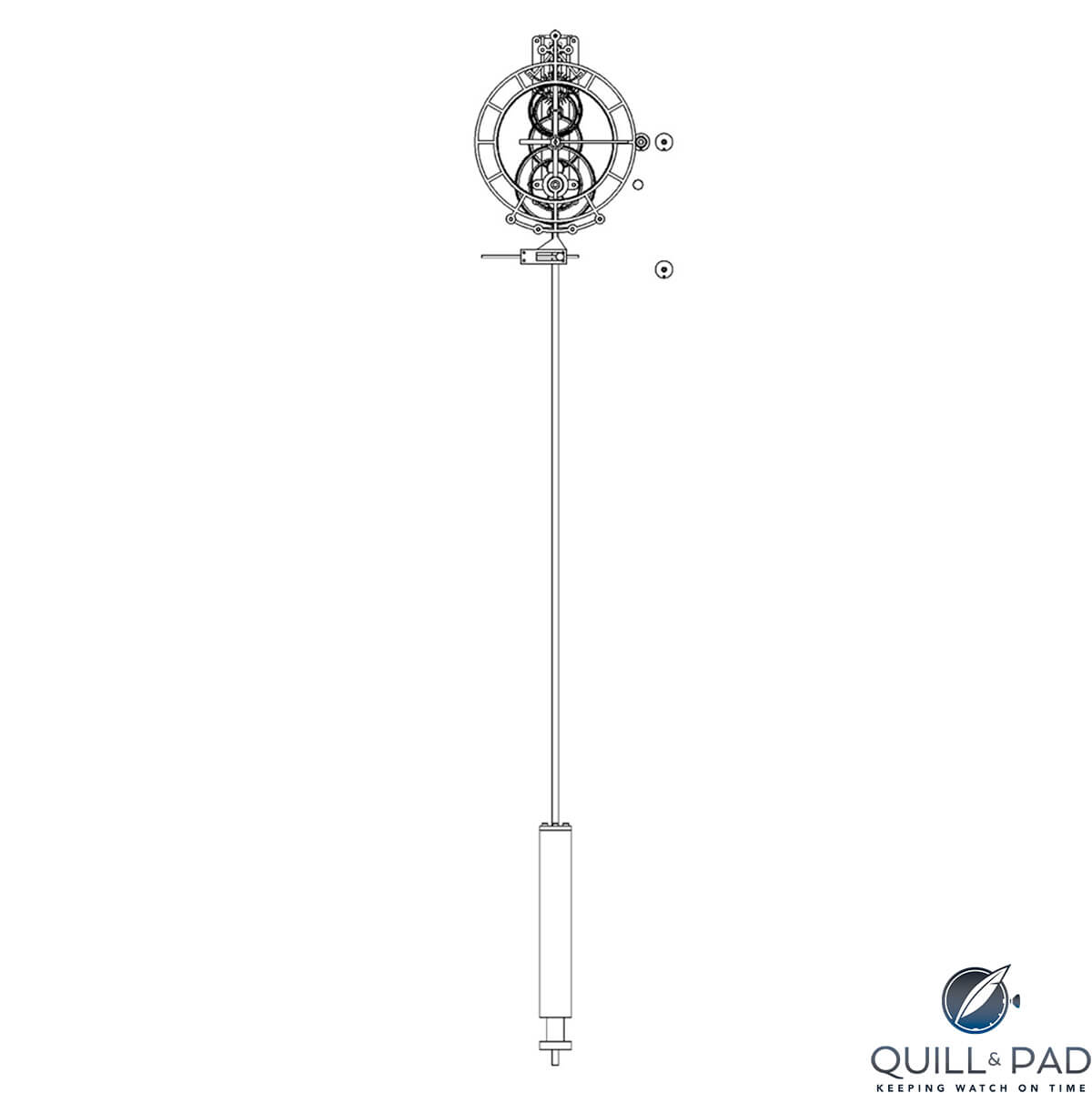

Earlier I mentioned that Sivaraman wanted to make an unconventional clock, but one that was very reliable and longlasting. Here are a few of the unconventional elements inside: planetary gear motion work; planetary gear maintaining power mechanism; Graham deadbeat escapement; friction clutch as rubber pad instead of bent metal spring; crutch rod not attached to the pallet arbor; and bob (weight) with integrated pulley inside.

Planetary gears

After the deadbeat escapement was chosen, the next step was the going train, those gears and wheels making up his movement. The internet is full of ideas for clock movements, but remember that Sivaraman’s main aims were reliability, longevity, and unconventionality. He was also working out for himself what should work best rather than simply copying an existing concept.

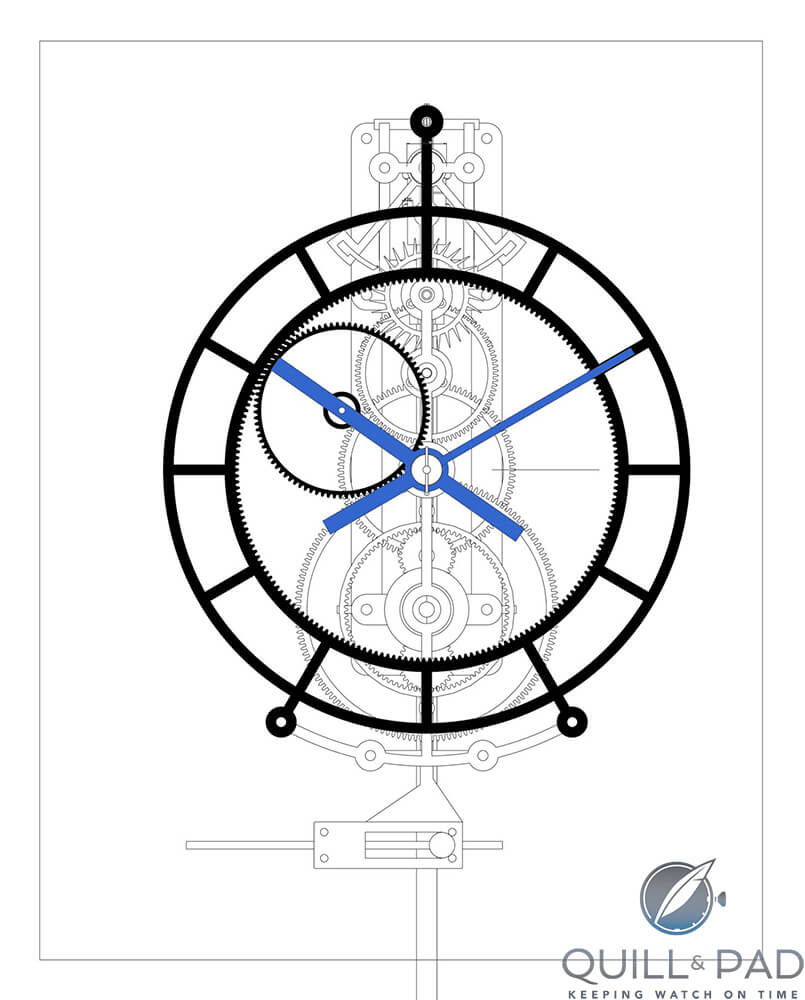

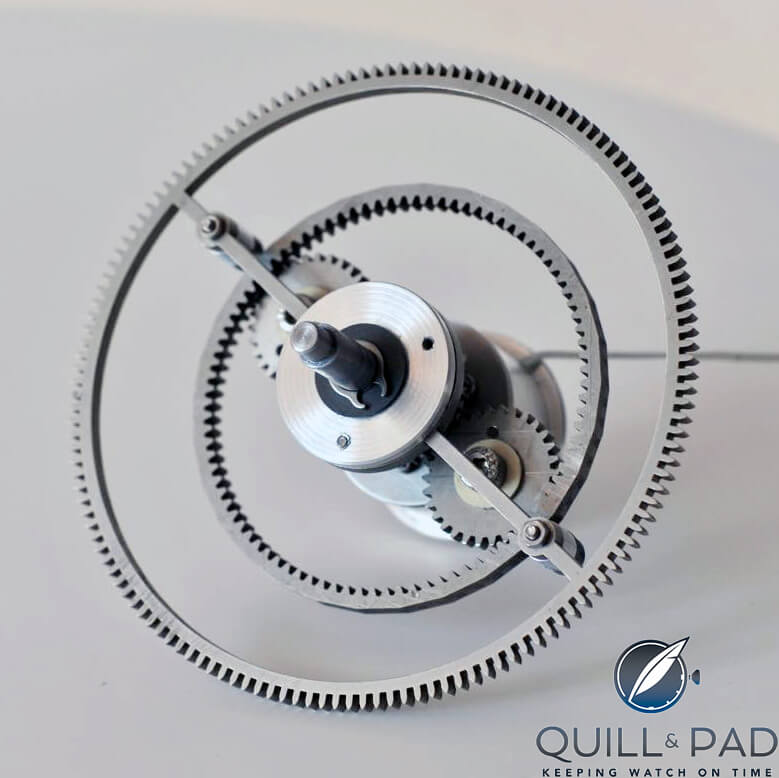

His studies led to the conclusion that planetary gears for the motion work would be best. The motion work is the 12-to-1 reduction gear train that converts the motion of the minute hand to power the hour. Now, it’s very unusual to see planetary gearing in clocks, but here is why planetary gearing is a good choice − and the following is blatantly lifted (and edited) from Wikipedia: “Planetary gear trains provide high power density in comparison to standard parallel axis gear trains. They provide a reduction volume, multiple kinematic combinations, purely torsional reactions, and coaxial shafting

“The load in a planetary gear train is shared among multiple planets, therefore torque capability is greatly increased. The planetary gear train also provides stability due to an even distribution of mass and increased rotational stiffness.

“The method of motion of a planetary gear structure is different from traditional parallel gears. Traditional gears rely on a small number of contact points between two gears to squeeze as the driving force, where all the loadings are concentrated on a few contacting surfaces, making the gears easy to wear and crack. But the planetary speed reducer has six gear contacting surfaces with a larger area that can distribute the loading evenly over 360 degrees. Multiple gear surfaces share the instantaneous impact loading evenly, which make them more resistant to the impact from higher torque. The housing and bearing parts will not be damaged and crack due to high loading.”

Well, that’s good to know.

Sivaramann explains his reasoning for the planetary gearing thus, “I found the planetary gear reduction very fascinating and really elegant. For the going train I used a conventional gear reduction method because an entire planetary gear train would mean all the wheels on one arbor.

“I decided to use a planetary gear reduction system for the motion work and then the idea struck to make the ring gear also double up as the dial chapter ring (with marking showing hours and minutes). In Gato, the chapter ring is also a fully functioning gear, albeit a stationary one. The carriage that holds the planetary gear in place becomes the hour hand. All these parts now multitask.

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”Just winding the clock is something I so look forward to every weekend, as it is a pleasure to see the planetary gears move around while weight is slowly pulled up.”[/pullquote]

“Another area where I decided to use a planetary gear mechanism was the maintaining power mechanism. I had read a lot of theory about such a system (it’s also called a sun and planet maintaining power mechanism). However, I did not find any examples of a working clock with this system online, although I’d heard that it was used in some clocks. This was not popular as cutting internal teeth was very difficult in the past.

“When I decided to use this system I did not know if it would actually work until I had made and tested a prototype and it worked like a charm. Just winding the clock is something I so look forward to every weekend, as it is a pleasure to see the planetary gears move around while weight is slowly pulled up.”

Clutch and crutch

The friction clutch, which allows the hands to move on their shafts when setting the time, is a rubber pad instead of the more usual bent metal spring clutch. Sivaraman concluded that rubber (or other elastomer) would offer more uniform pressure on the cannon pinion than the typical bent metal spring clutch.

Elastomer friction clutch (like thick rubber) on the Gato movement enables setting the time while the movement is running

The clutch is used so that time can be adjusted while the clock is still ticking. The hands are fixed on a cannon pinion, and the base of the cannon pinion pushes against the rubber clutch. This gives enough friction for the cannon pinion to turn, and in turn moves the hands.

The crutch is asymmetric and its rod is not attached to the pallet arbor. An asymmetric crutch is a little heavier than a traditional crutch and Sivaraman did not want to support it on the small 2 mm diameter pivot of the pallet. Instead, there are two shafts from the top and the bottom of the pallets that are attached to the crutch rod.

And that 1.8-kilogram weight at the bottom of the pendulum has a built-in pulley so that it looks cleaner and more streamlined.

And in conclusion

I have never dreamed of making a clock myself. However, I know quite a few people that dream of making a clock, and many of them are experienced horologists living in Switzerland, close to world-class suppliers and machinists for any component they could ever dream of.

Even so I do not know many people (outside the AHCI) who have made a clock. And that’s because it is difficult. Extremely difficult. If starting from scratch you need to understand physics and mathematics; be able to design a movement on a computer; understand gear ratios, torque, friction, metals, and lubrication.

And that’s before actually making anything, because then you have to know not only how to operate complex machinery to make components, you have to make them to small size with high precision.

And then the movement still needs to be assembled, lubricated, regulated, and cased, so you better learn a little carpentry, too, at least enough to make an informed opinion ).

Even if you are a trained watchmaker and you have access to the tools and machines required, making a clock is still difficult.

And, if you are a trained watchmaker and you have access to the tools and machines required, making a clock is difficult. But why not get out there and try? Even if you know next to nothing, Sivaraman shows that a dream with a good dose of motivation is enough.

Think how good that will feel. Stop planning and start making a clock!

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””] Stop planning and start making a clock![/pullquote]

When I first met Sivaraman at the Young Talent Competition presentation at Baselworld 2016 he was a finalist, not one of the three well-deserving winners. Yet even though the three winners had much more complicated clocks, and I generally appreciate more complication than less − within reason, and as long as it isn’t mine to service −I was drawn to this.

I was drawn to Sivaraman because I thought to myself, “How on earth did anyone in less than two years not only learn the theory of designing a clock movement, but also how to select materials, manufacture components, AND actually construct quite an unconventional long clock 100 percent according to the aim he set out to achieve?” That aim was to make a “perfect” clock.

I think he did. And imagine how good the next one will be?

Each Gato takes Sivaraman over four months to manufacture, so it may be a few months before we see another.

For more information, please contact Dilip Sivaraman at [email protected].

Quick Facts

Case: 1840 x 630 x 270 mm, Indian teak (or according to client’s preference); total weight (including movement) 18 kg

Movement: Caliber GT2.1, deadbeat escapement with tungsten carbide teeth, planetary gearing, two-spoke wheels, stainless steel components, weight (for power) 1.8 kg, pendulum bob 3 kg, all pinions 12 leaves, all arbors on ball races, escapement with ceramic ball races, Kevlar cord supporting weight

Pendulum: stainless steel, 1.8 kilograms, Delrin compensator, integrated pulley

Price: $16,000 including installation (excluding shipping and taxes)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Great job, Dilip.

Proud of you. You inspire me to work for my motive.

Dilip, You have proved that hard work, passion and persistence pays off. Well done and look forward to your next one.

What an absolute inspiration!

Hello,

Thank you very much to those commenting for the support. It is much appreciated.

Regards

Dilip

Thank you, Ian, for a fascinating and interesting article about a young, passionate talent pursuing the wonderful art of clockmaking. I love Quill & Pad for all the great education and discovery of those about whom I would never otherwise discover.

Congratulations, Dilip, and keep up the amazing, inspired work.

Best,

Jeremy

Dear Jeremy,

Thanks a lot for the encouraging email. I would be glad to hear your views on Gato. Do mail me if you wish to do so.

Regards

Dilip Sivaraman

Thanks for reading, Jeremy, great to see you here! 🙂

Good job on the clock! I too have similar beliefs and feel that objects have life forces. I always wanted a hmt watch in the 1970’s. I think hmt was a collaboration between Citizen/Japan and Tata, not sure. Thanks for sharing!

Dear Dan,

Thanks for your message. You can find HMTs on ebay these days. They’re still quite inexpensive.

Regards

Dilip Sivaraman

Wow! Such a great story and what a great looking clock…

Dear Ravi,

Thanks for the message.

Regards

Dilip Sivaraman

What a great story of your journey to find your calling, Dilip! Nine generations to cherish the most precious of all things finite – ‘TIME’

Now that’s some legacy!

Dear Jaishree,

Thanks a lot for your message.

Regards

Dilip Sivaraman

Hi Dilip,

This is a fantastic story. I wish you the very best. As I said on Facebook, it’s exciting to see someone sweat out an innovation. I’m your father’s cousin from Saratoga, California. (the late Parkutty athai’s daughter, Kalpana)

My post generated some wonderful comments. Here we go: https://www.facebook.com/kalpana.mohan/posts/10153557395429033?comment_id=10153557479914033&reply_comment_id=10153558526759033¬if_t=feed_comment¬if_id=1461042484003340

Your story resonates so much, down to the HMT on the wrist. But I’m still at the build a case for an old movement stage. You have inspired me to think bigger. Congratulations on your masterpiece!

Dear Steve,

Thanks a lot for your message. I would recommend you to take the plunge and make the entire clock. Its really liberating. Good luck.

Regards

Dilip

Congratulations sivaraman,you have proved nothing is exclusive technology to Switzerland,japan or France!hard work and efforts have bore the fruit ,to inspire other creative minds I have posted your story on Facebook.keep improving!

Congratulations Dilip..

Well done Dilip.

Display your clock at Samay Bharati Watch and Clock Exhibition at Mumbai

around 24th January 2018

This is what I did in 2007 and sold several skeleton clocks later on

Best of luck

Dear Mr. Mistry,

Thanks a ton for the advice. I will follow up on the exhibition.. I would also like to know about your skeleton clocks

Regards

Dilip

What is next after GATO

your GATO.

Yr WhatsApp where I can send you my clocks video

Great Dilip sir

Sir maine pinterest pe aapke baare me dekha aur apke clock story padha

Really I inspired sir

Mere paas bachpan se machanical clock Aur watch. the aur muze bhi uska working movement me bahot interest hai

Kal me just machanical Clock ke baare me search kar raha tha to aapke baare me info mili

And really I inspired

I would like to make such a clock

Lekin muze nahi pata ki kaha se start karna hai aur uske liye kya chaiye I means how I make aa gear and which type of machine required and that diagram

Actually it’s my dream

Hi there.Sivaram,

I would like to make a Grahams dead beat escapement weight driven clock.

Vaman Nayaks of Mangalore use to make them. They closed down a few years ago.

I am a 3rd Generaton watch maker Gani & Sons estd in 1909 in Madras. I shifted to Bangalore in 1979/ 80..

Pls email me when you are free . Thanks.

Shadman Namazi

Hi I am vipulmselara

From rajkot

I have a like old wall clock

There are old gears like Chiming clock Submarine Russian Clock I also make new stuff of Clock for myself in my factory also small shaft with material according to the company Small gears in my vaksonp all kinds of machinery if you need gear or any work related to it let me know This is just my hobby, my job is to export of engine part if there is any work, let me know on my email.