by Martin Green

The early innovations in watchmaking history clearly came about due to one clear focus: ladies’ watches.

And this is because women embraced the wristwatch decades before men did – the male species actually needed a world war to realize the functional value of wearing a watch on the wrist.

With early automatic watches the story was not dissimilar. When brands dreamed about a wristwatch that would wind itself, they dreamed of it inside the case of a ladies’ watch.

This story begins on the April 22, 1883 with the birth of Léon Hatot in the French town of Chatillon-sur-Seine. At the age of 12 he attended a school for watchmaking followed by art school, both of which were located in Besançon.

At the age of 22 Hatot had already set up his own business, one that was specialized in engraving watch cases made of precious metals. Yet being a successful entrepreneur wasn’t fulfilling the ambitions that Hatot had. In 1911, he moved to Paris, where he not only became even more successful as a businessman, but also made a name for himself as an inventor.

The perpetual dream

The Swiss brand Blancpain always had a keen eye for technical innovations and breakthroughs, and the late 1920s would provide the theater for one of the most important technical breakthroughs in watch history.

It all started in the early years of the twentieth century when consumer preferences began shifting from pocket to wristwatches with equal market share of 50 percent for each achieved by 1930.

With the increasing popularity of the wristwatch also came the “perpetual dream” of a wristwatch that never needed winding, one powered by the motion of its owner’s wrist.

Blancpain, realizing the potential of such a system at a very early stage, became involved in the project of John Harwood in the mid-1920s; Harwood was a gifted watchmaker with a vision to create a perpetual wristwatch. In 1926, Blancpain introduced an automatic watch outfitted with Harwood’s automatic mechanism.

The Blancpain Rolls by Léon Hatot (photo courtesy Geo Cramer)

Hatot’s own automatic

The year 1929 marks the point in history when Hatot and Blancpain met; and it was the year in which Léon Hatot revealed his prototype of a revolutionary movement with automatic winding: the inside of the case included a rail on which the whole movement moved up and down on ball bearings, powered by the motion of its owner.

Movement of the Blancpain Rolls by Léon Hatot (photo courtesy Geo Cramer)

Because the entire movement could move up and down inside the case, so could the dial, creating a rather unique perception of reading the time as the dial is rarely in the same place.

As much as this solution fulfilled the “perpetual dream,” it also caused some serious complications on how to set the time. Because the entire movement moves, a standard crown was not an option.

The top of the Blancpain Rolls case opens to allow access to the time-setting disk (photo courtesy Geo Cramer)

Hatot had to come up with a solution for that problem and he developed a disk to be attached to the movement to set the time. However, in order to reach this disk, one must open the watch case.

Time-setting disk revealed by the opening case of the Blancpain Rolls by Léon Hatot (photo courtesy Geo Cramer)

This may sound very inconvenient, but the case was designed in such a way that it was quite easy to open – and closed securely enough to protect the movement from dust and humidity.

But being a “perpetual” movement, it was not unlikely that Hatot considered changing the time as something one only had to do once or twice a year, depending how frequently and far the owner travelled.

The Rolls

The rectangular design of the movement was perfect because shaped watches like this were really en vogue in that decade. One other advantage was that the movement was small, which was perfect for use in women’s watches.

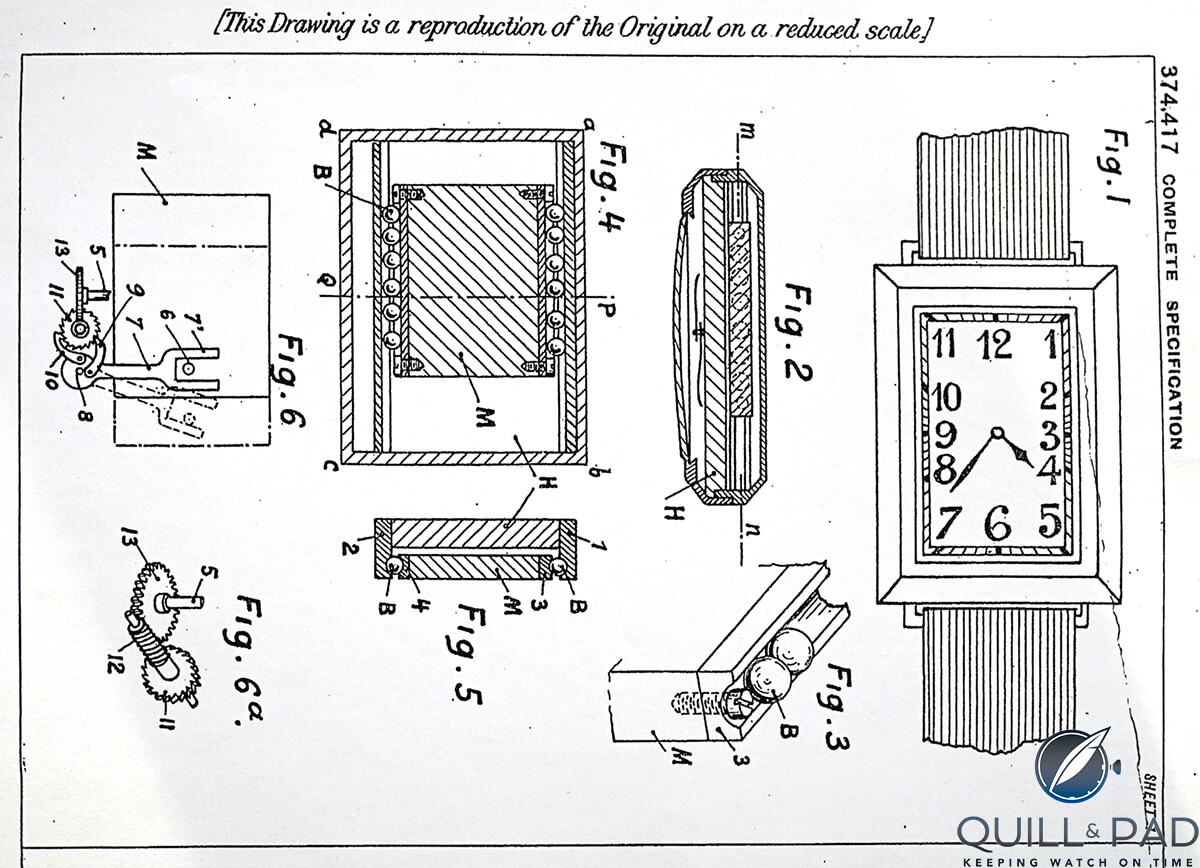

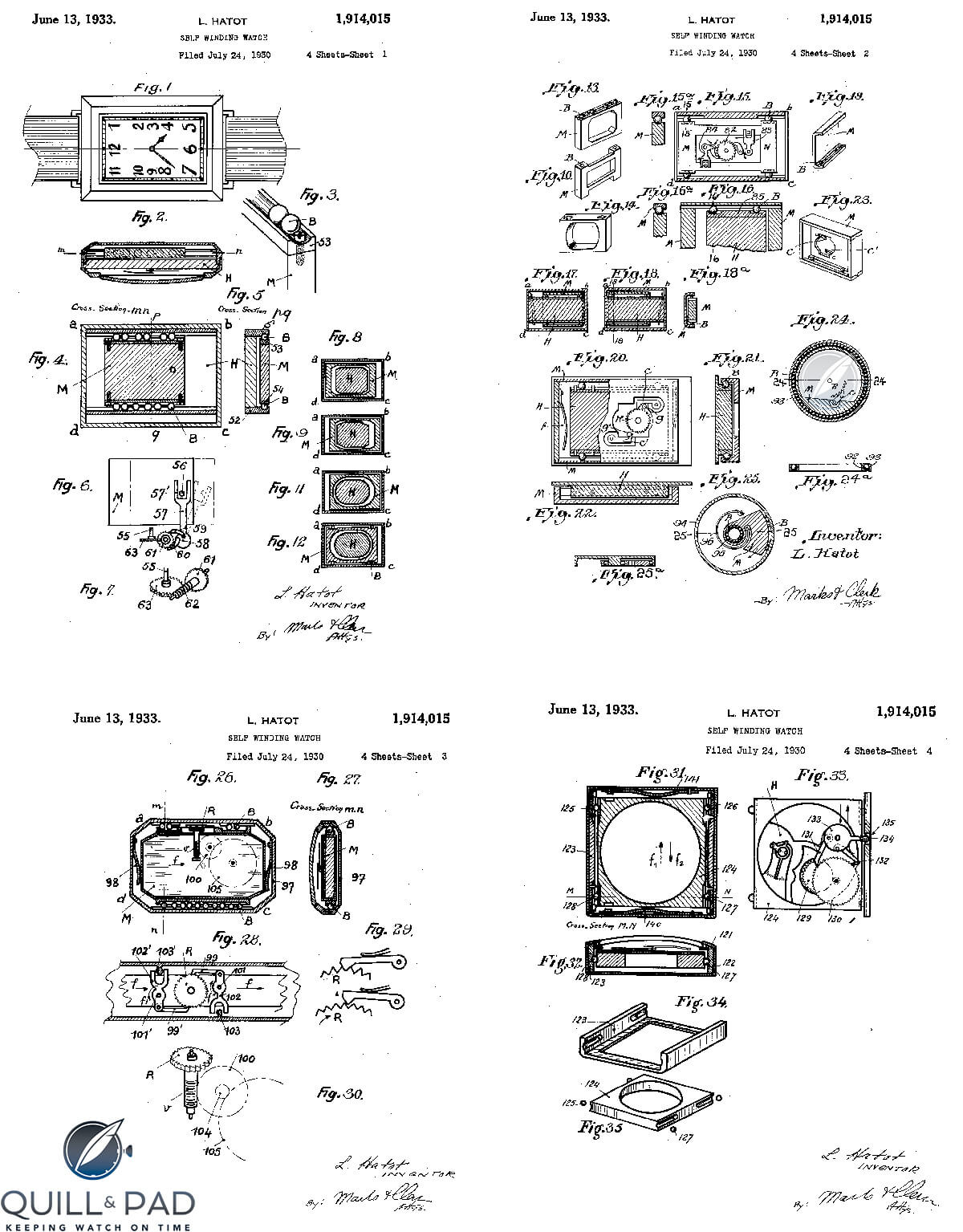

Patent of the Blancpain Rolls by Léon Hatot

On September 23, 1930 Frederic-Émile Blancpain and Léon Hatot signed a contract to make the production of this watch on a larger scale a reality. Their approach was quite ambitious because they made the movement in three sizes to fit not only the ladies’ model, but also an intermediate and a men’s model.

Patent of the Blancpain Rolls by Léon Hatot

The name “Rolls” for the model was actually Hatot’s idea, he thought that the Geneva stripes decorating the back of the movement showed a strong resemblance to the famous radiators of Rolls-Royce motorcars.

This was a well-chosen name for more then one reason; the movement “rolled” on ball bearings, and it was just as innovative and prestigious as the vehicle that shared the name.

The name was painted above the dial’s numerals and surrounded by a crest-like Art Deco drawing. Interestingly, the watch was not signed with “Blancpain” on the dial, you had to lift the movement out of the outer case to see the Blancpain imprint on the back of the movement.

Technically, the Rolls was a breakthrough, and this is perhaps best illustrated by the words of Hollywood legend and Rolls owner Joan Crawford, who called her Blancpain wristwatch “eternity in a box.”

The Blancpain Rolls by Léon Hatot (photo courtesy Geo Cramer)

Commercially it unfortunately never had a chance because by the time the first Rolls rolled into the stores, the world was already deep into the global economic depression. Despite this, and the fact that Frederic-Émile Blancpain died in 1932 with no immediate heir willing to take over the company, the Rolls stayed in production until 1934.

The fate of Hatot and Blancpain

Although never a true success in a commercial sense, and too inconvenient to become the standard for automatic watches, both Blancpain and Hatot would fare well after the project.

After Frederic-Émile Blancpain passed away, the family’s ownership of the brand ended since none of his children wanted to follow in his footsteps. The company was entrusted to Frederic-Émile’s assistant, Betty Fiechter. She would lead the brand with a steady hand for decades, introducing legendary watches like the Bathyscaphe and Fifty Fathoms along the way.

Hatot didn’t do too poorly, either. He continued his research and became one of the leading specialists in the field of electric clocks, continuing his quest of finding a perpetual solution to keeping accurate time. His legacy also laid the foundation upon which the quartz watch would eventually be developed.

Every watch tells a story

The Rolls photographed for this article comes with a story as well, although it has been passed on by word of mouth so no conclusive evidence exists that it occurred like this.

It is believed that this Rolls was sold in 1932 to a client in an Eastern European country, possibly Russia, where it remained for almost seven decades. We can only speculate about what happened during that time, but the wear on the watch shows that it must have enjoyed quite a lot of time on the wrist.

The top of the Blancpain Rolls case opens to allow access to the time-setting disk (photo courtesy Geo Cramer)

This Rolls then returned to Western Europe, where it was purchased by its current owner. It was in poor condition, but had been restored during its life, sometimes badly.

The dial was poorly repainted and incorrectly signed with “Blancpain” instead of “Rolls.” However, a full restoration was commissioned, which lasted more than a year, during which many challenges had to be overcome.

Although the watch was complete, some parts were badly worn and needed replacement. The original patent images were sourced, and the parts were handmade to get the watch functioning again. The dial was repainted to its original design, but there was still one issue: the characteristic Geneva stripes on the back of the movement were partially worn off by the movement rolling back and forth in the case for decades, a hallmark feature that gave the Rolls its name.

The Blancpain Rolls by Léon Hatot (photo courtesy Geo Cramer)

Since it was still partially in place, the current owner decided to have the back of the movement re-plated as was, making it a fitting tribute to the life this Rolls had.

Today it spends its days in a private collection, fully functional and occasionally even on the wrist, where it is admired for what it is: an intriguing part of watchmaking history that brought two historical names together to create a legendary story.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] At this Basel fair in 1925, Fortis presented the first serially produced wristwatch with automatic winding. The watch had no crown and the time was set by rotating the bezel. Blancpain and Felsa also introduced wristwatches containing the same caliber (see the Blancpain rendition in Eternity In A Box: The Blancpain Rolls Starring Léon Hatot Made Watchmaking History). […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

How many rolls watches were made and are they valuable

Hallo Sir!

I would be grateful to know the approximate price for such a timepiece in non-working condition.

Thanks in advance

Dmitri