by Martin Green

What sells watches? This is the 20 billion Swiss franc question in today’s challenging economic climate.

And as exports of Swiss watches continue falling for the fifteenth consecutive month, CEOs, marketing executives, and industry consultants scramble to answer this question.

However, I sometimes wonder if they are actually allowing themselves the time to even ask the question – let alone answer it properly. Perhaps the pressure of group executive boards pushes them into taking swift action in whatever direction seems most favorable at the time.

Such as going outside their comfort zones in the hopes of tapping into consumer markets that are outside their usual realms of activity (see Piaget Polo S: Outside Its Comfort Zone).

I think that this year a record amount of new brand ambassadors have been appointed: these are traditional celebrities such as athletes and actors, but also increasingly social media stars, who enjoy large followings on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, as brands try to engage the elusive millennials, many of who are even still figuring out if they actually like watches to begin with.

What to actually look for in a lasting purchase

For the answer to this we can learn a lot from two of the steadiest performers in the watch industry: Patek Philippe and Rolex. Perpetuating success requires impeccable quality. Rolex founder Hans Wilsdorf’s passion for over-engineering each component in his watches earned Rolex a spot as a solid performer from its early days onward. Less then impeccable quality can be compensated with lower prices and clever marketing, but when the market is going down expect sales of “lesser” brands to follow.

Rolex GMT Master II BLNR “Batman”

When a market falls, it is usually influenced by outside events: political unrest, stagnating economies, falling stock prices. These are examples of times when consumers slow spending on luxury items such as high-end watches, even if the events do not directly impact their incomes.

Patek Philippe Reference 5078P

But that is not all: not only does spending slow, consumers also adjust their focus – not only in terms of value for money in the direction of impeccable quality, but also value retention.

How much money is your watch still worth when you strap it on and walk out of the jewelry store?

How are vintage pieces by the brand valued?

How steady are the prices of second-hand pieces?

I would call Patek Philippe and Rolex the gold standard in terms of value retention in the watch industry, and the fact of the matter is that they often outperform gold as a safe bet when times are tough.

How did they become gold standard?

Patek Philippe and Rolex also obtained this position by being conservative in terms of styling. And whether you appreciate it or not according to your own taste, this has nurtured a recognizable brand image on one hand, while on the other it has created watches that appeal to the tastes of a larger demographic, simultaneously limiting exposure to slowdowns in the market as risk is spread over vastly different types of consumers.

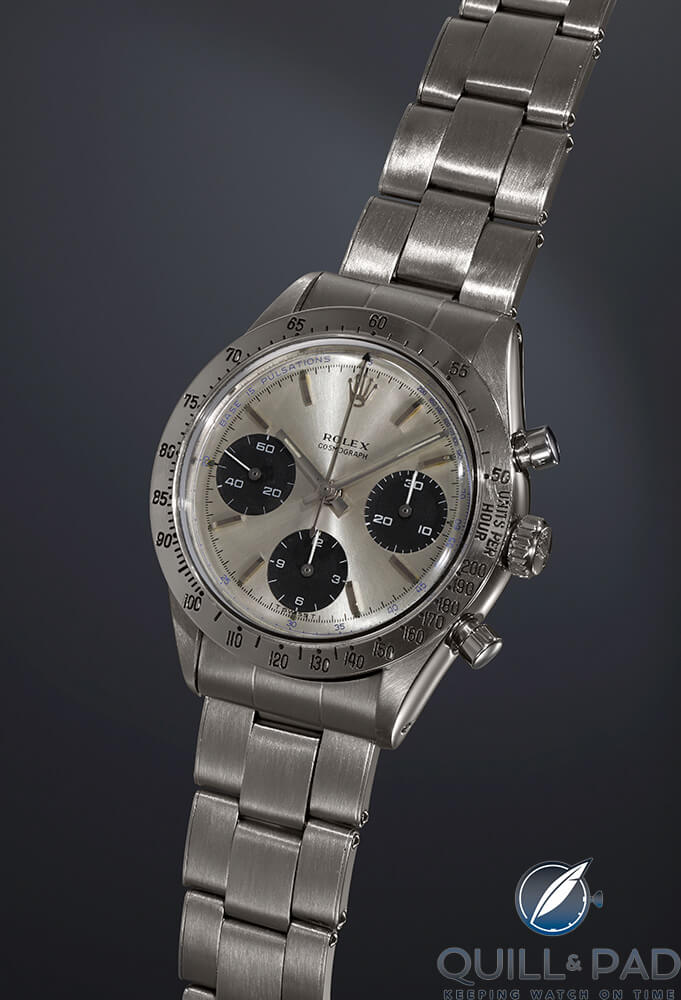

Rolex Reference 6239

In a twist of irony, overall rarity has had very little to do with this stability: the rarity of a Patek Philippe or a Rolex is not measured in comparison to other brands, but rather to their own brand populations. This is a very unique trait that only few brands have the privilege of experiencing.

The problem with these traits is that they are related to pedigree, which is something that cannot be obtained overnight. It has not been one watch that has defined these two brands; it has been the entire histories of their watch collections as a whole.

Being a consistent performer is a matter of restraint: in order to stay true and very close to your original brand “DNA” the trick is to restrain yourself when the markets are up.

Many Swiss brands have had a hard time doing this – particularly in recent years when previously untapped or little tapped Asian markets seemed to offer unlimited potential. But at times when it seemed quite easy to sell anything with a melodious brand name, it is also very easy for a brand to lose its true self.

This situation becomes magnified when the market shrinks again, and consumers, collectors, and connoisseurs re-evaluate how they spend their money.

If they spend it!

Why have Rolex and Patek Philippe been able to follow a steady course through their watch histories as a whole? Because they lack shareholders; because they are not part of larger entities; because the accountability for their actions is limited to people within the firm, not outside of it.

A grim scenario?

This may sound like a very grim scenario for other haute horlogerie brands not carrying Rolex or Patek Philippe logos on their dials.

And although many of these are part of larger groups or have shareholders, these two brands do help provide clues and answers for others.

Patek Philippe Reference 1518

In general, ships like to avoid storms. But when they cannot, they approach each wave head on. Although not foolproof, it provides them with the highest chance of actually making it through.

So my advice to brands at the moment is this: instead of going outside your comfort zone, go right back into it. It is very unlikely that you are going to excel at something you have never or rarely done before, but don’t be so quick to willing to abandon the field you have already mastered.

It will not be painless, just as taking each wave head on in a storm is far from pleasant. But the odds of making it through might be the best odds you are going to find.

Likewise, my advice to consumers: look for brands that stay true to themselves. These will prove the best value for money and enjoyment in the long run.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] You might also enjoy: Buying (And Selling) Watches In Tough Economic Times. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

The industry is dying a slow death and a lot of it is self-induced. IMO, the average person no longer relates to the brand(s) or their ambassadors. The industry should begin to moderate prices and appoint ambassadors that are more representative of the working man and woman who value precision and owning something that can be passed down (legacy and heritage). If things don’t change the mechanical watch industry will be effectively gone from the general population landscape in 20 years and seen only among the uber rich class…

I absolutely agree. The averag middle-class person can’t afford to pay $5000 USD for a watch. The only way I can even begin to participate in watch collecting is due to the fact that I have no children, and both my wife and eye have decent jobs. Even then, it’s a pretty hard sell to go to my wife and discuss spending $5000+ on a watch. It usually means forgoing a vacation that particular year. The only way the industry is going to bring in new consumers is to lower prices. PERIOD. I mean c’mon, isn’t it smarter to cut prices and survive, rather than to keep raising prices and be dead in twenty years? The after purchase costs must go down too. I just got an Omega back from a tune-up at the cost of $700+. In addition, Omega wants $495 for a rubber replacement strap. Two pieces of rubber that MIGHT cost a nickel to produce. And they aren’t the only ones doing it. I love Omega watches, but they have just about priced themselves out of my range. I really hope I can keep participating in this hobby and not just reading about it.

Staying true to oneself. Important in watchmaking and in life. Wholeheartedly agree.

I think that’s an interesting insight, and wholeheartedly agree with this analysis. However, I believe this exercise is not complete without the mention of direct external threats, in terms of technological advancement and the resulting consumer-perceptions.

The current smartwatch crisis is pretty much a repeat of the quartz crisis almost half century ago. For true mechanical watchmakers to brave the tide, a new strategy has to be formed.

Or, “if you can’t beat them, join them” may not be such a bad idea for some brands/parents to follow.

Smart watches are not watches. Apples and oranges.

Mechanical watches are here to stay for sure. Yes, they may cater to the well-off, but they always did. Nothing wrong with that. It would not even be possible to produce enough mechanical Swiss watches to cater to people for low prices. Nobody has that kind of production capacity. Why I believe that mechanical watches are here to stay? 2 reasons. First, look at the vintage market. There is a growing demand for vintage mechanical timepieces primarily Swiss made. Second, look at the history. For centuries, the mechanical watch, even during the quartz crisis, had its place in society. I do not see a reason why that should stop now? The circles who love Swiss made mechanical watches are not big, many collectors know each other around the globe. That is a good thing.

I do not see the smart watch as a danger. The only danger I see looming is the improvement of replica watches. They are not necessarily coming from China anymore, but from countries that are able to produce high-end replicas that look extremely close to the real thing. It will make it harder for the consumer to buy secondhand, and they will have to trust certain trustworthy dealers in the scene.

Even the current turmoil will pass by. After rain comes sunshine…

History is repeating itself. This is a boom and bust cycle of capitalism. This is the bus cycle for the watch industry. Nobody can afford $4000 watches one are you guys in to realize that. When half of the people on the United States 11 below the poverty line only so many rich people can buy these watches .

TO buy a very expensive watch ought to be like buying a Mercedes and not a Rolls Royce, you cannot have a show off item in the vast majority of circonstances and it should not be priced like a Maybach either.

Today however brands have tried to to prices themselves as Rolls Royce as a starting point rather than earn this right, look at catalogue prices for a number of the brands for the same watches from 2004 to today, they at least doubled if not far more.

That is the easy path to make money, and like anything easy it tends to encounter the hardness of life sooner or later.

This industry’s cost base is probably 1/3 to 50% marketing, which means half of my watch purchase is spent on making me believe I should be paying more. I do not feel in any way sad for them.

I believe what is changing is not the fact that people buy less watches (1/nobody can really tell how many watches are truly sold) but the way we buy watches. The retailers are suffering for sure and cannot compete with the grey market. These same retailers today are not only selling watches but trading as well. So embracing the grey market seems a way to get their clientele still come to their stores. But how do you count the sale of a traded watch? it’s one-for-one, two-for-one or one-for-three watches. This inventory movement is impossible to be catalogued in the annual sales tally of the watch industry but is such a growing market. In my own experience, I deal with few jewelry retailers and I can do business with what I already have on my wrist. Sometimes a straight trade means no taxes or any money exchanged. This is what I believe the main concern is for the industry.

There is an over abundant number of old new stock sitting in the jewelry stores collecting dust and in order to purchase new current timepieces from the design homes, they must be selling old stock off at auctions, eBay, massive exposure by social media and sell off to grey market at break-even cost or trade.

I started to loose interest in watch collecting when the price of a PP Calatrava went from $10,000 to $30,000 in 2 decades , and Omega prices , as already mentioned , have escalated likewise ,

not , i suspect , because of a proportionate increase in production cost , but simply to increase the perceived luxury status of the item . Even a billionaire , at some point , expects something resembling value for money . $4000 steel bracelets , $900 basic services , $500 for a leather strap no bigger than my index finger , there comes a point when , no matter how much you like a hobby , or want an object , you say to yourself , ‘ I’m being screwed ‘ .