Biologically speaking, making a baby is quite an undertaking for humans.

The process requires a multitude of things to go just right to even have a chance to conceive, let alone bear a child. A feat of biology and evolution, and given the variety of ways in which living things procreate, viviparous reproduction can be rather complicated.

The perfect alignment of factors needed becomes even more unlikely when the possibility of multiple births is considered.

Having twins, which results from either two separate eggs being fertilized (fraternal) or from a fertilized egg splitting before developing further (identical), has only a one-in-30 chance of occurring compared to the total number of births per year, whereas having triplets has even less likelihood: just one in 1,000. And for identical triplets instead of a set of identical twins and a fraternal third, the chances drop dramatically to anywhere between one in 10,000 to one in a million.

Quadruplets are even more unlikely with odds that haven’t ever been accurately calculated due to the low number of quadruplets in the world. A decade ago the number of quadruplets in the world was 3,500, though with the increase in use of fertility drugs quadruplets are becoming slightly more common.

Still, the sheer biological and environmental requirements required to produce the absolutely perfect conditions needed to result in quadruplets is astonishing. Making four of something that is already extremely complicated is disproportionately harder.

Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

That is why the mere existence of the Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor is incredible with its quadruple angled balance wheels. This latest take on the Quatuor model, the Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt, reignites earlier amazement over such a complicated piece with a new process and material for the case that would make a nerdy metallurgist stand up and take notice.

Metallurgy makes it possible

What makes the Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt so special is right there in its name: Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt. This refers to the cobalt used in the construction of the case, a metal previously not used in this function.

The basic alloy is a cobalt-chromium mix with small amounts of molybdenum, nickel, manganese, silicon, and iron which, given the general whiteness of the alloying elements, allows the cobalt-chrome to appear very clean and bright, closer to platinum as compared to the slightly warmer hue of white gold.

Of course, the cobalt-chrome is much, much harder and resistant to wear than either platinum or white gold could ever hope to be (for a comparison on white metals see Here’s Why: Stainless Steel Is The Most Precious Metal).

Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

The exact alloy isn’t actually specified by Roger Dubuis, but the MicroMelt material was developed by metallurgy specialists Carpenter Powder Products. Based on the fact that Roger Dubuis mentions its 100 percent biocompatible nature, this narrows down the possible alloys to pretty much one.

Unless Roger Dubuis worked with the producer to tweak the formula (which admittedly is very possible), the alloy is likely to be the CarTech® Micro-Melt® BioDur® CCM® Alloy (whew, long name) used in the production of orthopedic medical implants and other advanced components. And while that is an awesome new use for a very cool metal, the process of producing that metal is where the magic lies.

The basis for the MicroMelt technology is the creation of clean, contaminant-free powdered metal that is transformed into a stronger and more homogeneous solid bar for further processing. It starts with a conventionally produced alloy billet being placed into a vacuum induction melting furnace to be – you guessed it – melted.

An electric current is used to melt the billet in the vacuum chamber (the process of induction melting uses physics and magnetic fields to create heat with no contact or contamination), and the molten metal is further refined before being injected into a high-pressure stream of inert (non-reactive) gas.

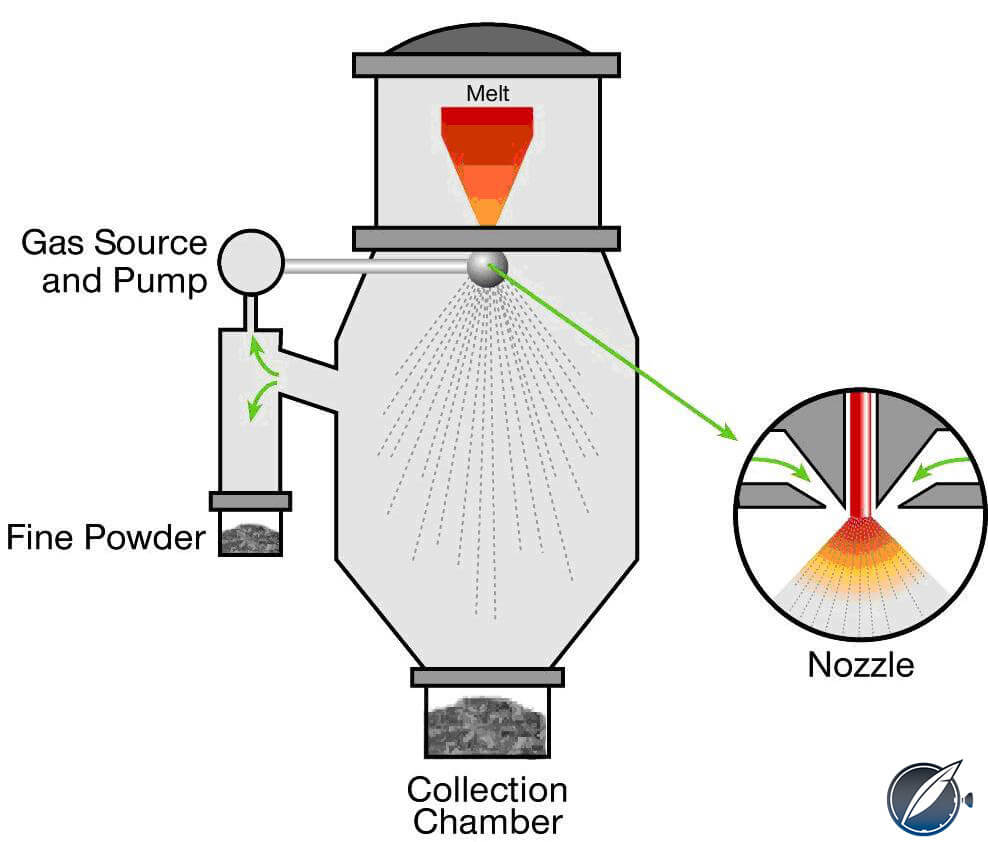

The Vacuum Inert Gas Atomization (VIGA) process (image courtesy LPW Technology)

This process, called Vacuum Inert Gas Atomization (VIGA), atomizes the molten metal, solidifying it mid-flight and turning it into a powder of very small spheres of highly homogeneous, rapidly cooled alloy. The big advantage of this process is that it creates an extraordinarily clean powdered metal, which is crucial for the creation of super alloys and metals.

The powdered metal is then sifted through screens to create batches of consistently sized particles that are used for slightly different purposes based on the particle size. The similar batches are then blended together before being put into canisters for hot isostatic pressing (HIP) in which the metal powder is placed into a pressurizable chamber that is filled with an inert gas, usually argon, to prevent any reaction or oxidation.

The chamber is pressurized and heated; the increase in temperature causes much of the pressure increase. The pressure commonly reaches around 1,000 bar (15,000 psi), and while temperatures vary based on the specific alloy, they are usually approximately 80 percent of the melting point, which for cobalt would be around 1,200 degrees Celsius.

This pressure compacts the material evenly from every direction (hence the use of the word “isostatic”) producing a very evenly grained, void-free material, something unachievable by conventional methods. The material is then hot-worked (formed while at temperature) to produce bars that can be processed, machined, and ground into the final case shape.

The importance of homogeneity

The steps involved in the creation of this MicroMelt cobalt-chrome alloy are what separates it from “average” cobalt-chrome alloys. The process is a great way to achieve high uniformity and small dimension in grain size, increase in tensile and fatigue strength, increase in hardness (for impact resistance), and a structure that is less prone to segregation.

Segregation is an aspect of uniformity as pockets of the alloy with slightly different properties or grain size will group together, creating an overall structure that has varying hardness, possible porosity, and variations in grain size. The MicroMelt process greatly reduces segregation and creates an overall better material more resistant to wear and providing excellent long term strength.

Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

The increase in uniformity can also reduce the scrap rate during production, as conventionally wrought bars are more likely to be rejected due to porosity, bubbles, or inclusions that render a partially machined component useless. And the only way to know the material has issues is to machine it.

The much more consistent and uniform material ensures the parts will be problem-free after machining.

That doesn’t even mention the fact that thanks to the process of production, the metal forms a very strong protective layer thanks to passivation, a chemical reaction taking place on the grain boundaries of the metal to precipitate carbides (a much harder material) that resist corrosion and abrasion. This is a permanent condition that “self-heals” itself should a scratch or gouge occur.

Also, the cobalt-chrome alloy is a multiphase structure in terms of the nanoscopic crystal structure. The orientation of the atoms within the molecules are specific to each element, so with alloys the combination of specific crystal structures can lead to unique, improved, mechanical properties. This alloy greatly benefits from the chemical occurrence.

Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

There’s more than just the case material

The design of the Excalibur case echoes the reality of these properties with the hard, notched bezel, and the movement inside follows suit. Its hard angular bridges and color scheme stand out boldly from within. If this was a “standard” Roger Dubuis skeleton movement it would be amazing already, but since it is the inimitable Quatuor movement it reaches a whole new level.

The quadruple balances are evenly spread around the movement, linked via a total of five differentials, creating a very distinctive look. The cutouts in the movements displaying the suspended balances make for a central movement seeming to float, more so than the previous versions of the Quatuor.

Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

The RD101 Quatuor movement is characterized by an open design with a minimized dial, allowing the mechanics to be fully on display with the rear holding nearly as much interest as the front.

The differentials, winding mechanism, going train, and the balance and escapement supports are all visible and perfectly balanced across the movement. This is also where you might take note that the entire movement, in its extreme modernity and design, meets all of the requirements for the Geneva Seal and is marked with it.

View through the display back of the Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

This is noted on the dial, but the evidence really shines on the rear of the movement. Of course being eligible for the Geneva Seal means the complete watch is 100 percent Swiss made, and every single component is entirely finished to exacting specifications.

The movement is a wonder, comprising 590 parts (113 of those being jewels) that took more than 2,400 hours to manufacture. Out of that time, more than 700 hours were dedicated strictly to Geneva Seal requirements. While the main focus of the new Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt is the super-strong case material, that movement still is the reason we’re all here.

Roger Dubuis Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt

I’m happy that the Quatuor isn’t a one-off showcase piece ready to disappear into a collector’s vault.

Instead, Roger Dubuis continues to do unique things with one of its wildest movements. Given the direction the brand has taken with exploration into new materials and usage of established materials, it bodes well that we shall see continued exploration from the manufacture.

If the Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt is any indication, it should be pretty interesting.

And even though the cobalt chrome MicroMelt is extremely tough, I’m gonna break this down!

- Wowza Factor * 9.78 Quadruple balance wheels, five differentials, and a super-strong case to protect the amazing mechanics definitely deliver a wow!

- Late Night Lust Appeal * 95.5 » 936.535 m/s2 The late nights are spent learning all about metallurgy so that the lusting is backed up by data. Then you can justify the desire!

- M.G.R. * 70.4 Even though I didn’t talk at length about it, the quadruple balances tied together by quintuple differentials is enough to make this mechanism nerd go slack-jawed!

- Added-Functionitis * Mild It should be no surprise that the more incredible the mechanics, sometimes the less complicated the displays. A power reserve bumps this from nothing to something, but you’ll only need children’s strength Gotta-HAVE-That cream for the deceptively mild swelling.

- Ouch Outline * 11.6 Getting your hand caught between a rock and a hard place! As a climber, this actually is a huge fear of mine and the reason I will never watch the movie 127 Hours. This might be the one that I would hesitate to do to get the Excalibur Quatuor Cobalt MicroMelt on my wrist, but it would be a tough decision!

- Mermaid Moment * Instantaneous! This is also the amount of time it takes for the Quatuor to compensate for any positional errors thanks to the four balances and five differentials. Sounds like I’ll need to book a caterer rather soon!

- Awesome Total * 720 Divide the number of beats per hour each balance completes (28,800) by the number of balances there are (4), divide the result by the number of differentials there are (5) and finally divide by the number of mainspring barrels keeping the movement humming (2) for one humdinger of an awesome total!

For more information, please visit www.rogerdubuis.com/roger-dubuis-takes-quantum-leap-next-excalibur-aeon/.

Quick Facts

Case: 48 x 18.38 mm, Cobalt-Chrome MicroMelt material

Movement: manually wound Caliber RD101 with four free-sprung balances at 45 degrees and five differentials; blue PVD-coated plate and bridges; 16 (4 x 4) Hz frequency (115,200 vph); Seal of Geneva; 40-hour power reserve

Functions: hours, minutes; power reserve

Limitation: 8 pieces

Price: 390,000 Swiss francs

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] Duotor is descended from the Quatuor, the four-balance movement debuted in 2013, but it utilizes only two balances and one differential, […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!