by Ian Skellern

Watch brands, retailers, distributors, and collectors alike have known for at least a decade that the internet will revolutionize watch retailing just as it has already revolutionized books (Amazon), music (Apple iTunes), television and films (Netflix), travel (TripAdvisor), and so much else.

And while collectors have been hoping and praying that the revolution comes sooner rather than later, leading to better value for money (and perhaps a better buying experience in general), brands, retailers, and distributors have basically crossed their collective fingers, squealed ineffectually about the grey market that they created and continue to nourish, and with a few exceptions just hoped for the best.

Look how that turned out for the music industry.

But over the last couple of years, and even over the last few weeks, there have been ripples in the watch retailing universe – a trickle of initiatives that may (or may not) quickly turn into a flood. I am predicting that as soon as a few more major high-end brands embrace internet sales on a user-friendly, multi-brand platform, the flood gates will open.

Here are a few of things that you may have missed but should be aware of:

2015: Richemont signs agreement to merge the Net-A-Porter Group with YOOX Group, at the time the global leader in retail for leading fashion brands. YOOX Net-A-Porter (YNAP) is now a massive global internet retail sales platform for many leading fashion brands and no doubt for many leading watch brands in the not-too-distant future.

2015: Richemont then invites LVMH to join the YOOX Net-A-Porter platform to compete with Amazon. Bloomberg News reported that Richemont group chairman Johann Rupert said at a conference in 2015, “’We’re not big enough, what I said to them was they can come in and get equity in the company if they commit their brands to sell via the platform.”

IWC on the Mr Porter internet sales platform

2016: Richemont brand IWC launches sales on Mr Porter, a Net-A-Porter platform (I expect more high-end Richemont brands to follow).

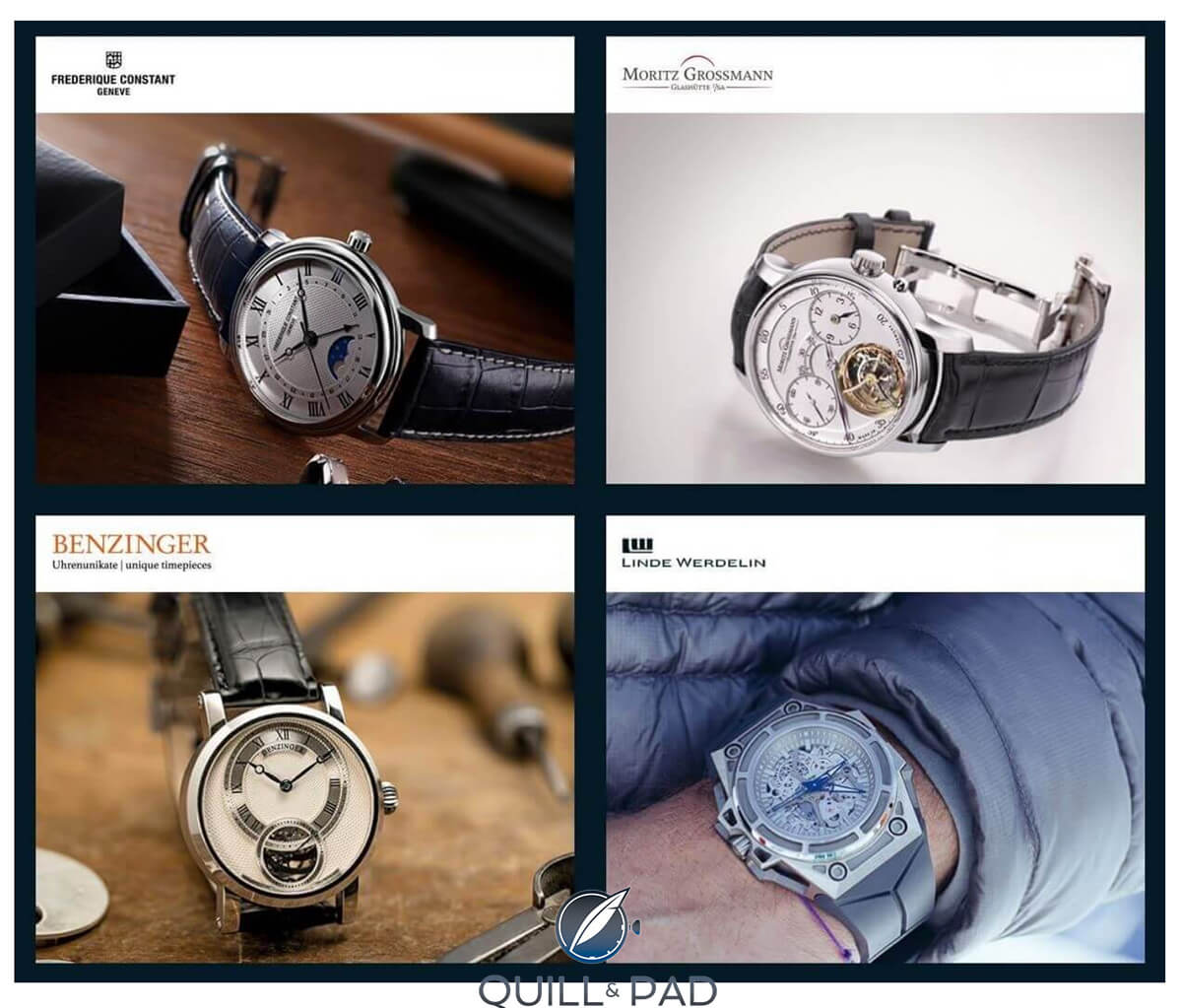

2017: Without fanfare, Chrono24, the world largest internet sales platform for both used and new (grey market) watches, listed a “Brand Boutique” section that is an official online retailer for Benzinger and Moritz Grossmann, two small though high-end brands that by themselves would be cause for comment. But also listed is the higher profile Linde Werdelin, which is a small brand that has been selling watches on its own website for years. Again, interesting but not earth-shattering news.

Chrono24 “Boutique Brands” include Benzinger, Moritz Grossmann, Linde Werdelin, and Frédérique Constant (with more sure to follow)

But Frédérique Constant, which was bought by Citizen in 2016, is big news (see Citizen Acquires Swiss Frédérique Constant Group As Port Of ‘Citizen Global Plan 2018’).

Frédérique Constant is a large Swiss manufacture with an estimated 3,000 retailers selling around 200,000 watches per year mainly in the $1,000-$5,000 range. It is a big, serious brand and it’s now officially selling watches via Chrono24.

And I’ll bet those sales bring in a lot of interesting data that many other large brands would love to get their hands on.

Many haute horlogerie brands and upmarket retailers have been telling themselves for decades that clients might buy cheaper watches online, but wanted the luxury personal boutique experience for more expensive models.

And for some clients that’s true, but they are likely to be an ever smaller percentage of the retail client base. You only have to look at how many sales of expensive watches at auction go to online or phone bidders to appreciate that buyers are ever more comfortable with buying with clicks rather than bricks.

That’s the good news regarding watch retail evolution, but there’s this . . .

Many, if not most, watch buyers do not know or realize that they are not the clients of most watch brands: in the vast majority of cases, the collector is a client of the retailer, not the brand.

This becomes obvious when visiting a large watch exhibition like Baselworld or the SIHH (which is now opening to the public) for the first time: collectors are surprised to learn that they have more chance of seeing the latest models by their favorite large brands at their local retailers than at the fair.

Except for the smallest of independents that sell both direct as well as to a few specialist retailers, the clients of the largest brands are distributors controlling the sales rights of countries and even continents and for medium-sized brands the clients are retailers.

This geographical carving up of the globe worked well until around 20 years ago because international air travel was expensive, even for those who could afford to buy expensive watches. Brands could set fixed prices, and collectors had few options for comparing prices and few options as to where to buy and how much to pay.

But as the cost of international flights dropped and more and more people flew internationally for both work and pleasure, those interested in watches soon realized that there were considerable savings to be made from buying in countries outside their own.

And in the last few years, it has become relatively easy to compare prices and buy new watches from any major retailer in any country and have the watch directly shipped door to door.

But while watch collectors now have the option of comparing prices and buying worldwide, large retailers cannot openly compete internationally because of the restrictive geographical contracts they have had to agree to for the right to sell the larger brands.

A brand or distributor will give a retailer the right to sell in a specific region or country, and if the retailer breaks that agreement it risks losing the right to sell that brand. Retailers still sell and ship worldwide, but it’s done quietly.

That’s why you don’t get the big retailers offering their own online sales platforms. The best retailers would like to compete internationally, but can’t. And while there have been a few high-end brands experimenting with selling on their own websites, the revolution is likely to have truly arrived when there is one dominant multi-brand digital sales platform.

The future: some predictions

The runes are not looking good for the watch retailers as they are losing ground on three fronts:

- They no longer “own” their local or regular clients as exclusively as they once did as collectors are ever more comfortable buying from whoever offers the best price and service.

- They cannot openly access and compete in the larger worldwide market that the internet offers because of restrictive geographical sales agreements.

- Large brands and groups like Richemont will soon be selling directly to consumers worldwide thanks to tried-and-true sales platforms like YOOX Net-A-Porter. That will cut out the middleman: the retailers.

On the plus side for retailers, especially high-end retailers, many customers will want and be happy to pay extra for exceptional personal service and experience. And many, if not most, collectors will still want to try before they buy.

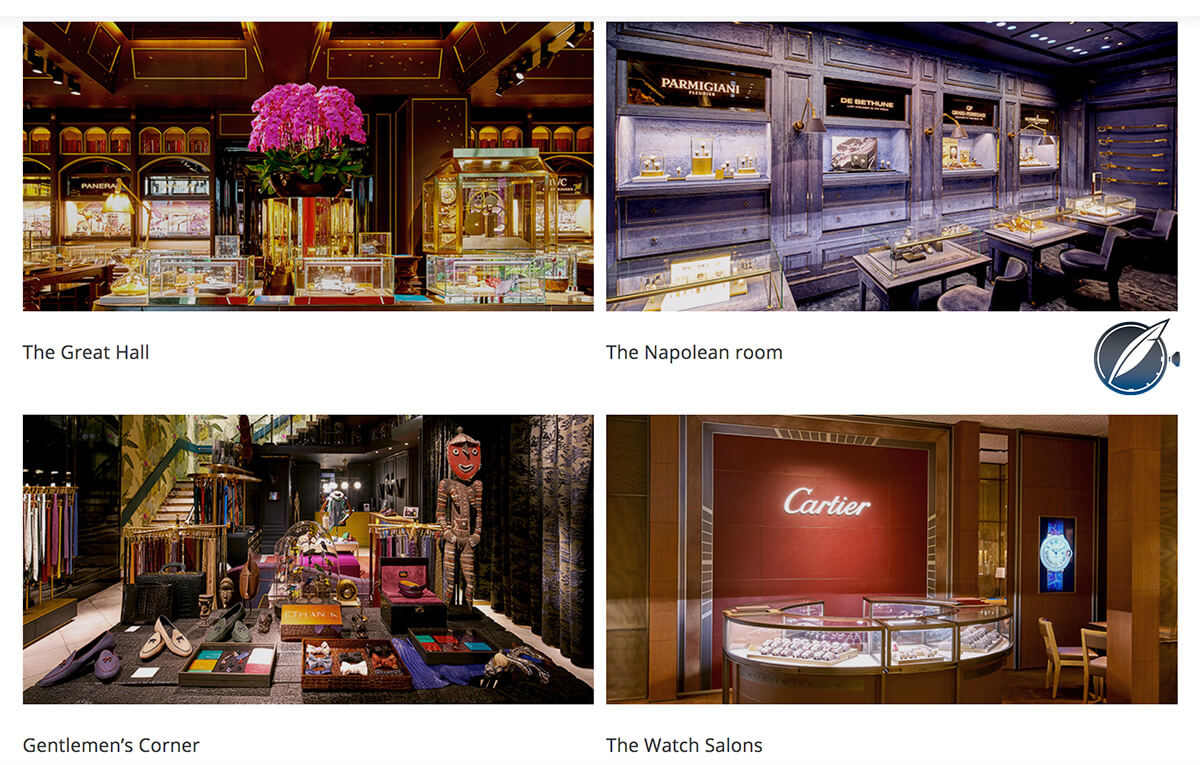

Malmaison by The Hour Glass offers an immersive luxury experience

My prediction is that brick-and mortar retailers will transform into three main categories:

- The luxuriously well-appointed boutique with well-educated staff offering an exceptional retail experience. Malmaison by The Hour Glass is an example of this.

- Retailers owning/managing monobrand boutiques, which become mainly a place to try on watches in a setting and environment controlled by the brand.

- Low-margin retailers offering a place to try on watches by many brands, but carrying little stock as the orders and delivery are managed by the brands. These will also handle after-sales services paid using a rate set by the brands.

On the internet retailing side, experience has shown that size is everything and the first big multi-brand platform to get things right is likely to clean up. If Richemont can make LVMH an offer it can’t refuse regarding taking a stake in the YOOX Net-A-Porter platform that could well be game over, especially if it is open to the smaller independents as well. YNAP could easily become the Amazon/eBay of horology.

Swatch Group, which has generally been a decade behind the curve with everything digital or web-related might well try to develop its own platform out of pride, but would be much better joining a platform that worked and already had large market share.

Naturally, something will happen and all of my predictions will be completely wrong.

But one more important factor has to occur for the watch industry to set itself up for a healthy future in the digital age: stop the over production. You can either sell exclusive low-volume luxury with high margins or high-volume mass market products at low margins. The present crisis is largely caused by brands trying to have it both ways because that’s what worked in the pre-digital age. That’s over (unless your name is Rolex).

What do you think will happen in the watch retailing future, and, more importantly, what would you like to see? Please leave your thoughts in the comments below.

You may also enjoy Navigating The Grey Market: A Retail Expert Explains The Whys And Wherefores.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] the tsunami of online sales outlets – which has decreased the need for traditional buyers. See Bricks And Clicks, Bricks Or Clicks, Just Clicks? There’s A Watch Retail Tsunami Coming, But How, … for more on that […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

In the next decade many brands are going to get absolutely crushed in my view. I have been a pretty comprehensive follower of the auction market for recent (since 1990) highly complicated (perpetual calendar chronograph, and grand complication) major brand watches since the mid-late 1990s and in my view the auction market serves as a good barometer for where the watch market as a whole is going in the near future. The auction market went crazy in the 2,000s auguring the modern mechanical watch renaissance and in my view it is serving as a real canary in the coal mine for a serious contraction of the market in the near future. Secondary market values have always been pretty awful for anything not unique, historic (in the real sense rather than auctioneer speak) or by Patek/Rolex, but over the last few years pieces which I would consider almost bulletproof have been getting absolutely brutalized in the auction market and a number of even higher profile pieces that in the past would have been snapped up instantly have been going unsold for conspicuously long stretches (most notably the recent Patek Caliber 89, which before failing at auction had (according to my sources) been flogged across the private sales marketplace like a foundering horse). There are too many recent examples of auction carnage to list here, but If you want to confirm what I am saying, look for any highly complicated, mass produced non-Patek made in the last 20 years and you will see a yawning chasm between what it was going for a couple of years ago and what it will go for now, if it is even sells. Even more stark are the more niche pieces, such as watches with diamonds, grand feu enamel pieces, and high complications from brands that aren’t in the top tier. Additionally, even watches whose auction prices appeared on a rocket-ship to the moon like Patek Perpetual Chronographs and Greubel Forsey Tourbillons are suddenly crashing down to earth.

These auction prices are but one sign among many of a very rough period coming for the watch market. Another is the gray market problem. But why is this happening? In my view there are three main reasons.

Reason 1: there are too many brands and they are making too many watches. Very simply, as watch prices rose rapidly and manufacturing difficulty declined (especially for highly complicated watches) during the boom years brands kept making more inventory and new brands kept popping up as a shockingly unconservative Switzerland appeared to think the Years of crazy market growth would never end. If you want confirmation read LVMH and richemont’s shareholder reports, or just speak to any gray marketer about the amount and prices of watches they are getting offered. Most worrisome is that even if watch brands constrain supply to match demand to keep their margins, the secondary and auction markets will still be glutted with excess supply from the previous few years. Additionally, consumers are much more agnostic about where they get their watches and given the condition many of these watches will be in (effectively unworn), brands will have a hard time convincing many of their customers to pay full price for a new watch when they could get last years model for 50-70% off (or more!).

Reason 2: China. The effects of the Chinese economic slowdown and government fight against corruption have robbed a badly overextended industry of one of its largest and fastest growing markets. Additionally, a nervous china has flooded the secondary market at a time when it was already very sensitive due to over-production.

Reason 3: A demographically different watch-buying public with a very different conception of the watch market and their time-pieces. This last point is much more speculative but I also think incredibly important. Anecdotally (though I have lots of individual anecdotes, I have no hard data to back this up) the watch buying public sells their watches more frequently, is much more willing to buy at auction or grey market, and is generally much less sentimental about their purchases than their grandparents were. It used to be most watches were worn for decades before coming to market. Now, many watches are never worn, before being effectively traded for other watches. This different customer, as you astutely note in your article is happy buying online, at auction, and from the gray market and this is the most worrying trend. Because unlike with the traditional distribution method watch companies don’t make a profit on used, auction, or grey market sales, and if prices must collapse for volume to stay the same, or volume must be constrained for prices, the watch brands that currently exist will not all survive. They are just ovextended. If a new factory is underutilized the loans a company took out to build it may bankrupt them. And I badly fear that we are only beginning to ride the wave of this massive supply glut as it impacts a supremely unready watch market. Watches are a luxury and luxury tastes change. Rather than compare the watch market to music and its disruption by the internet, a much more frightening comparison I have heard from Switzerland (in off the record conversations) is to the ultra high end luxury sedan market in the early-mid 20th century which went from hundreds of small to medium size shops that handmade everything, often completely bespoke for a single customer, with many brands using engines and other major parts from ford or GM, and the value add being in the interiors and other parts which were hand-made by people who had held the same job in the carriage industry. Increased automation, an overly saturated market, overseas competition offering similar quality for a cheaper price, and changing consumer tastes means the only surviving companies are the very strongest like Rolls Royce (which is actually owned by BMW). As a watch lover this comparison seems worryingly plausible.

Thank you for those well-reasoned thoughts, Noah. Regarding comparisions with the luxury car market, a senior Richemont brand CEO revealed at the SIHH that the aim for the group was to share “platforms” (read: movements) among brands like VW/Audi/Seat/Skoda do. The rationale is that the vast majority of clients (much of the present company excluded) have little interest in the mechanics as long as the watches look good, work well, and the branding resonates.

That bodes well for the independents if they can get their acts together.

Regards, Ian

A quick scan of a few randomly selected watches at MrPorter suggests they are charging rather a lot, ceratinly more than the current grey market – hard to see that working!

For me personally, it’s bricks and clicks at trustworthy grey market shops.

Great analysis by Noah!

I am probably unique among readers here in that I am not a major collector. I began collecting watches around 10 years ago, collecting middle of the road, uncomplicated watches from the 50’s and 60’s. After a while I got annoyed with what I felt was the downside of watches that were decades old, their timekeeping always needed adjusting to get decent timekeeping.

Today i am stunned to say that new, uncomplicated watches seem to barely fall within the widest variation allowed in their specs. It seems absurd to speak about the care and pride involved in fine watchmaking if they seemingly can not spend 10 minutes adjusting to precise timekeeping. Maybe I missed the point, If COSC specs allow 5 seconds a day they really try to hit that 5 seconds off exactly so that a collector might yearn for better. A recent ETA movement (not COSC) that was off by 17 seconds a day when new spent 6 weeks being adjusted. Despite paperwork that said it was now 9 seconds fast/day it actually timed to 17 seconds/day after repairs.

This collector is tired of the shenanigans and suspects more feel the same way.

Ian, great contribution. And the comment by Noah was very interesting to read as he is covering the bases of the upcoming trends and how they may or will affect watch brands and the whole watch industry.

While a lot of people are favoring the grey market, even that market is coming under the gun as too many participants are trying to get a piece of the cheese. In addition, the investor mentality about watches (vintage and used and possibly NOS 10 or 20 year old watches) is causing a disruption as well, I believe. This mentality means that people want a “deal”. They are not willing to pay much. They need to make profit, but the profit-making chain is not endless, and a lot of clueless people may get burned as dealers try to work around that mentality with fakes, frankens, and manipulated timepieces, where just one expensive part is changed with an unauthentic part to sell the whole watch for normal money while having the part to achieve profit. The whole industry on every level seems under the gun. The ghosts of the grey market are coming to haunt all the brands.

The whole auction world of the big auction houses seems to work on a whole separate level with clients that buy the best pieces and are willing to pay any price for them. Even in the vintage market, top pieces sell for absolute top money, even by a normal dealer who is not one of the big names. But we are talking about very few pieces out of a huge market.

I am close to the customer and get a sense that the tsunami is under way. It may reach the shores soon. The consumer has expectations that are rather unrealistic, be it pricing or condition or even overall valuation of the watch he wants to sell or buy. The gap between reality and dreams is widening. And at the end of that trend there will be punishment. Let’s see how it goes, 2001 and 2008 we had some taste of what we may be expecting.

Honestly, it will be interesting to see how things unfold in the coming 5 years…

And at the end of the day, those who enjoy the watch they wear, what do they care about its value development. And if some big investors in the business fail, like we have seen Auctionata and other companies fail recently, it only helps those surviving. It is a dog eat dog world, just this time the dogs eat the watches… lol.

Interesting comments by Noah and others. In response to Noah, point by point: 1) Too many Swiss brands have existed for about 20 years. It’s relatively easy to start a brand, with many Swiss cases and other key components made in Asia since the 2000’s, and Switzerland’s onerous bankruptcy laws prevent unsuccessful watch companies from getting out of the business. 2) The Chinese market was destined to fall. It took off like a rocket, remained high for many years and fell to the dismay of the Swiss who bragged about sales there for years. Many Swiss manufactures have typically looked for and focused on “plum” markets rather than developing their brands across multiple markets simultaneously. 3) You’re correct that the watch buyer has changed. As you noted, watch buyers today are far more knowledgeable, largely because of excellent information about pricing, manufacture, distribution, and other details being widely available on the internet. Additionally, buyers are more fickle and less trusting of Swiss manufactures, which

have historically not been forthcoming about where many components of “Swiss” watches were made.

Hi Ian, great insight and i read it again because i cant find the name of a recent ( this year..??) started online market place for small/independent (from Switserland ) watchmakers, also aimed at limited production runs. Can you help me with finding that site again ?

Thanks

Hi Ron, do you mean Skolorr? https://skolorr.com/

Yes ! perfect thanks Elizabeth.