The “Industrialization Of Arts & Crafts”: Is This The Unspoken Tagline Of Many (Most?) Haute Horlogerie Brands Today?

by Ian Skellern

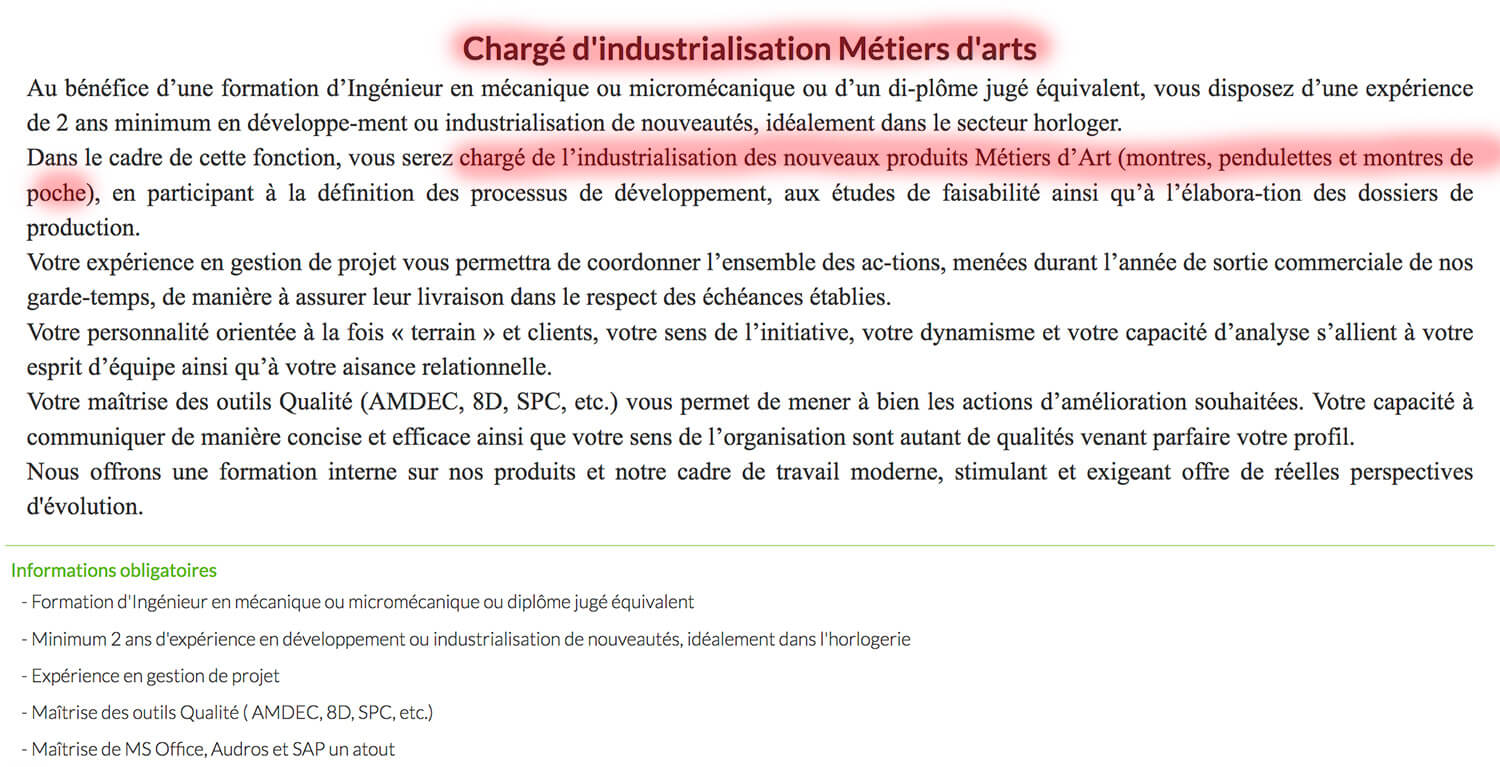

There was a small horological polemic recently out of Geneva caused by an employment advert from a high-end watch brand looking for a “chargé d’industrialisation métiers d’art” (“manager for the industrialization of métiers d’art”). Responsibilities include (my translation from the French), “. . . the industrialization of new métiers d’art (watches, pocket watches, and clocks).”

The brand advertising the position isn’t important as when one of the major brands does anything to save or make money, you can be sure they either all are doing the same or soon will be.

Watch brand advert for a ‘chargé d’industrialization métiers d’art’

The industrialization of métiers d’art

I’m a realist, and therefore it’s important to face the fact that big haute horlogerie brands are either owned by groups and/or investors demanding ever-increasing profit growth or private individuals demanding a competitive return on investment. And that’s not a bad thing: loss-making businesses help nobody, and profitable businesses can afford to invest for the future in employees and R&D.

Evolution in the commercial world will always tend toward better value for money (for the brand if not the customer). That’s why so many people today can afford to buy a Rolex (and do): a watch offering reliability and precision at a price that Abraham-Louis Breguet and John Harrison could not have even dreamed of in their most fervid imaginations.

The lower end of the market is supposed to be mass market so I’m giving that a pass here, but the upmarket sector is supposed to be exclusive. That’s surely what luxury is, isn’t it? Exclusive.

If something is ubiquitous, not only is it not luxury it’s the antithesis of luxury.

As with cars, so with watches

In the early days of the automobile, cars were so rare that any car at all (and they were very basic) was an incredible luxury: a seemingly unessential expense only a few could afford. However, as cars have become ubiquitous we don’t even pay attention to these sophisticated machines unless they sport a badge denoting “rarity” in some form or another.

Cars today are much better and much cheaper than those made in the past and, in general, it’s the same for watches, all thanks largely to industrialization. The vast majority of wristwatches today, compared to those of past decades, are cheaper, more reliable, more precise, more water resistant, and last longer between services.

And that’s a good thing. Isn’t it?

Well, industrialization in the sense of “making better/making more efficiently” is a good thing if you are selling normal goods like cars for day-to-day transport or watches as tools for indicating the time. Making more of something is a tried-and-true method of bringing unit costs down and quality up, all hail mass production; however, while partially fueled by lower costs, industrialization does mean creating larger demand. Profits per unit are low, but volumes are high.

If the price is competitive and the need (for transport or telling the time) is there, demand is likely to rise. But what happens when there is no need for the object in the first place? Like a mechanical watch, no need for it at all.

Then you market it as “luxury,” a status symbol, an example of the world’s finest craftsmanship. In luxury, volumes are low and profit margins are high.

After the quartz crisis of the late 1970s, luxury watch brands not only revived, they thrived (hence the attraction to the groups).

But thriving wasn’t enough.

The industrialization of crafts

Then came the industrialization of crafts: robots replaced watchmakers and machines replaced men; their skilled handcrafts, particularly in finishing, were conquered one by one. Geneva waves, perlage, polishes, and now even internal anglage are all being applied by machine.

It seems that every mechanical watch now has a display back revealing an apparently (to the untrained eye) nicely finished movement: it’s become ubiquitous.

Taking expensive watchmakers out of the process both saves money and increases quality (people can make mistakes), so the industrialization of crafts looks like a win-win. And it would be if the demand for the now more efficiently mass-produced watches had risen in line with their production.

But it didn’t.

Watch retailers were (and many still are) overstocked.

Discounts abound.

Reputations taint.

The whole market is still suffering from the over-production caused by the industrialization of crafts. What should the high-end watch industry do, go even higher upmarket? No, the strategy seems to be when customers go high, we go low!

The industrialization of crafts went so well, let’s industrialize art too!

Double down on going down

It’s no use fighting the direction the industry is going because it’s just following its natural path. But it hurts. ” The industrialization of métiers d’art” should be an oxymoron, but it’s not; it’s standard operating procedure for the industry behind haute horlogerie.

It hurts because the top brands do invest heavily in métiers d’art, be that engraving, enameling, guilloche, miniature painting, and much more. And it’s likely that by industrializing (aka mass producing) these miniscule artworks, the artists themselves may become better known and their work better appreciated.

The problem is that all depends on increasing production, and unlike machines the best artists are not as easy to replicate or scale up. Using machines mass production leads to better quality at lower costs. With a limited number of artists, however, the only way to increase production is to lower quality.

Or not bother pretending to make art at all: think of an industrialized print reproduction of a painting.

But, whatever happens, volumes go up: what was rare luxury becomes relatively ubiquitous, and the awe fades.

There are examples of brands that have, at least until now, succeeded in mass or industrialized luxury: Rolex and Apple, which mass produce products in the millions while enjoying the premium profit margins of exclusive luxury. The allure of mass-market high-profit margins is understandably irresistible despite the oversupply caused by industrializing so many highly skilled handcrafts.

Rolex and Apple sell quality, not art, and they rarely produce more than the market demands. Reacting quickly to market downturns by reducing production isn’t the strategy watch brands have ever shown much talent for.

But there’s hope.

Conclusion

While the car industry has been industrializing luxury for decades, it’s likely to be haute couture that provides a better indication of what may happen in haute horlogerie. The big luxury fashion brands make headlines with incredibly creative (and expensive) handmade clothes that are sold to a tiny section of the world’s wealthy, and this exposure helps market the brands’ main industrialized, mass-market, prêt-à–porter business.

The big risk for brands is in tarnishing their reputations for excellence, but perhaps that’s more a problem for us than them: Mercedes-Benz used to be able to claim to make the best cars in the world with some justification. That’s long gone, but the brand still thrives making larger volumes of both cars and profits.

I’m sure that the larger brands will continue to create the minimum number of true métiers d’art timepieces to attract our attention, just like haute couture brands do at fashion shows or car brands do with concept cars, but that will be just to help shift the large numbers of still expensive, but relatively affordable, “prêt-à–porter” watches. Their reputations for excellence are likely to gradually fade, to be hopefully replaced by reputations for value for money.

The big brands will continue to commission talking-point art pieces, but these will have less and less relationship with the main business, and that will be obvious to clients and collectors.

My hope lies with the small independent brands. If these, or the best of them, can get their acts together regarding marketing and communication, I predict that they could be the winners of the bigger brands’ general move down market because the independents offer both more authentic horological craft and a stronger connection with art and craft.

Big brands exist solely to make money. If they cannot do that they die. That’s not to say that big brands don’t make great watches, it’s just not their primary purpose. Making money is.

For the small independent watchmakers, though, it’s the opposite: most would make more money working for a big brand than for themselves. They are driven by the desire to create superlative art and craft for their own sake rather than as a means to an end (more profits).

These independent watchmakers and creators are true artists so they cannot be scaled up or replicated to increase production: their timepieces will always be created in small numbers so they will remain exclusive.

Further reading: You might also enjoy reading about two successful independent brands that do not want to grow, but for very different reasons at Urwerk Vs. MB&F: How Do They Square Up?

Bravo Ian for having the courage to write about the deviance or shall I say greed of certain “manufactures” ! You are very elegant not writing the name of the brand incriminated, but unfortunately they’re neither the worst, nor the first…. Watch brands are showing a rare talent of destroying dreams, first the tourbillon turned a common object, and now the métiers d’art.

Your comparison with the cars is excellent, you could have added the perfume industry, where they’re even better at destroying dreams. And for the luxury brands capable of mass producing there would be a few more names to add, such as Louis Vuitton.

The good news is : when you have mass producers on one side, you create niches for the real artisans !

Some excellent points well made.

Very interesting article and opinion! However, I think the industrialization and automation of the industry will have greater consequences. Once robots and artificial intelligence are able to assemble any mechanical watch (so not purpose-designed system 51 types) and to finish them at the same level as a very good craftsman, what will it mean for the industry? Will prices go down or be maintained artificially high to increase margins, for example by limiting production numbers? Will the future be total customization (there are already watches with customized rotors on kickstarter)? If build and finish quality are not distinguishing features, will it be movement design? If both assembly and finishing can be fully automatized, could we see haute horology watches for less than 500 USD (for mass produced watches where the cost of creating an in-house movement can be spead over tens of thousands of watches)? Sorry I have more questions than answers, but it would be great if you could write about this topic and maybe ask industry experts how they see the industry changing in the next 10 years or so (linked to automation, not smartwatches).

Truthfully, what you just described is already here: Rolex. And that gives you the answer, too.

But Rolex isn’t pretending that it’s movements are anything but industrial, they make no secret of the amount of robotization.

Many haute horlogerie brands on the other hand, convey the impression that each piece is hand finished to a level comparable to Philippe Dufour, Greubel Forsey, Romain Gauthier or Kari Voutilainen, when the reality usually very far from that.