Have you gotten into a new auto lately? Have you noticed how much of it drives itself? If so, then you probably understand that a new generation of automobiles has arrived that has begun to change everything about the car as we knew it.

Well, new components have now arrived in watchmaking that have the same opportunity to change everything about the genre used in combination with silicon: compliant parts.

Zenith Defy Lab on the wrist

The successful implementation of such a component in a new concept watch by Zenith called the Defy Lab even caused TAG Heuer chairman Jack Heuer to exclaim at its live launch in September 2017, “A few years from now the old mechanical watch style will probably be forgotten to a degree.”

What is a compliant mechanism?

The Defy Lab is not the first wristwatch to successfully implement a compliant component in its mechanical movement. That honor belongs to Patek Philippe, who in March 2017 introduced its Reference 5650G Advanced Research Aquanaut Travel Time, which contains a compliant subassembly replacing the conventional time zone setting mechanism. It effectively reduced that subgroup from 37 individual components to 12 and its height from 1.45 mm to 1.24 mm. See Give Me Five! All 5 Of Patek Philippe’s Advanced Research Limited Editions for more.

Returning to my above-posed question – what is a compliant mechanism? – I can most easily answer with, “A component that relies on the elasticity of materials to replace mechanical joints.”

Since the type of compliant mechanisms in use here are single-piece structures, there is no need to assemble individual parts, further reducing the energy-robbing friction inherent in all mechanical movements.

Additionally, the compliant mechansim uses its ability to “deform” to transfer energy.

These two base elements make it a pretty perfect technology for use in a mechanical movement.

The high-tech wafer manufacturing process used at CSEM to make the Zenith Defy Lab’s compliant silicon oscillator

Unlike the Patek Philippe watch, which uses the compliant mechanism to replace the functional subassembly of an added complication, the Zenith Defy Lab’s movement contains a monolithic silicon whole to replace what is perhaps the heart of a mechanical movement: the oscillator – which is the subgroup that portions energy and sets the timekeeping beat.

The Defy Lab’s compliant mechanism replaces about 30 parts that require assembly, adjustment, setting, testing, and lubrication, including the balance wheel, the balance spring, screws, inertia weights, the pallet lever and pallets, and the regulation assembly as well as a variety of bearing jewels and pivots. These are now replaced by one single component only 0.5 mm in height. In contrast, those some 30 components would normally have needed approximately five millimeters’ worth of valuable space inside the watch case.

So this new technology could also make watches thinner in height should their maker choose to have them do so.

The experimental Zenith Defy Lab was first offered in a set of 10 unique pieces to collectors

The Zenith Oscillator in Caliber ZO 342

Zenith’s Caliber ZO 342 with its compliant monolithic regulating organ made of silicon coated with a layer of silicon oxide beats at the incredibly high frequency of 15 Hz (108,000 vph).

Zenith Caliber ZO 342

This frequency pays tribute to Zenith’s history in high frequency, beginning with the El Primero caliber, which made its debut in 1969. This caliber, still in use today, beats at 5 Hz (36,000 vph); an unheard-of pace from 1969 all the way into the late 1990s.

The primary goal of higher frequency is more precision – but that comes as a tradeoff against wear and tear of components, something that silicon relieves to a larger degree than traditional metals.

The Defy Lab’s frequency of 15 Hz is obviously three times faster than that of the El Primero. “This is to demonstrate in 1969 that we had frequency of 5 Hz to get power reserve of 50 hours,” Guy Sémon, head of the research and development division of LVMH, Zenith’s parent company, said at the launch. “With this system we upped it by three times to get 60 hours of power reserve, a demonstration that the system is accurate and consumes less energy.”

The silicon oscillator/escapement in the Zenith Defy Lab

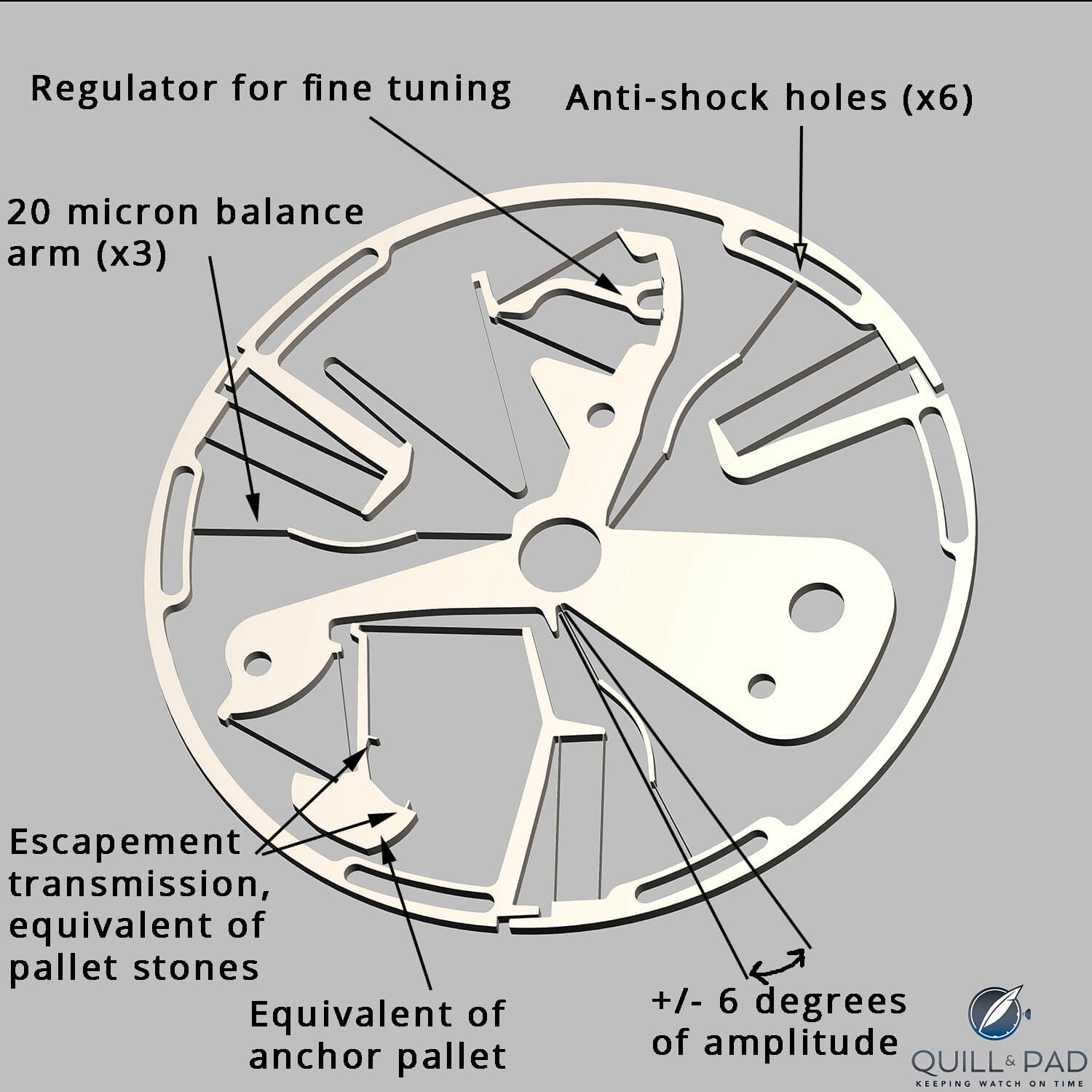

The complex compliant mechanism described above has 20 different flexures, the thickest of which is 20 microns. The use of silicon allows insensitivity to temperature, gravity, and magnetic fields as well as no need for lubrication – the bane of the mechanical watch.

Its outside ring (frame) is equivalent to the actual balance wheel, while the three visible “spokes” equal the hairspring and also carry the balance wheel, regulation assembly, and pallets. Sémon declared that this movement achieves rate precision within one second in a 24-hour period (though, confusingly, the press kit states 0.3 second). Despite the inaccurate communication, either way it far outclasses what is needed to achieve official C.O.S.C. certification, which is -4 to +6 seconds (10 seconds) per day to be chronometer accurate.

Moreover, the new Zenith oscillator has been tested to maintain the same degree of precision for 95 percent of its 60-hour power reserve. Conventional watches tend to start decreasing in accuracy after 24 hours of the mainspring unwinding.

The silicon oscillator/escapement in the Zenith Defy Lab

Additionally, thanks to its improved energy consumption, it is not affected by the all-important amplitude (maximum angle of balance oscillation) like a conventional mechanical watch; this oscillator’s amplitude is just +/- 6 degrees. In comparison, a “normal” mechanical balance amplitude should be between 180 and 315 degrees depending on the type of watch.

The regulation assembly, which Sémon refers to as the “raquetterie,” modifies the stiffness of the spokes using the variable inertia principle. “We adjust the frequency by +/- 300 s/d, equivalent to adjustment of classic hairspring active length,” he explained.

Zenith Caliber ZO 342

The escape wheel, which runs so quickly it is hard for the eye to follow, is not included in the compliant oscillator mechanism. Its functionality, which Sémon told me is based on a Graham escapement principle, is made of silicon “on the same wafer as the silicon oscillator.” It does generate a “tick-tock,” like a classic mechanical watch, but with much less noise due to the faster frequency.

In fact, because of this decreased noise the watch’s rate cannot be measured by a typical Witschi timing machine. So the developmental team had to build a special test bench for it at CSEM, where the silicon components are also manufactured, using laser measurement.

The new oscillator is triply certified: for chronometer certification by the Besanҫon Observatory on behalf of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; for ISO standard 3159 (thermal behavior); and for ISO standard 765 (magnetic criteria; it withstands 88,000 Amperes/1,100 Gauss).

Zenith Defy Lab on the wrist

The Zenith Defy Lab’s case

Though the appearance of this case is very “Hublot,” meaning it wears its origin as a brainchild of LVMH watch division chairman Jean-Claude Biver and his team on its sleeve, it has its own charm in light of this timepiece being a concept watch. And this is not too surprising considering that Hublot’s head of research and development, Mathias Buttet, and CEO Ricardo Guadalupe filed its patent.

In my opinion, the futuristic quality of the case matches the purpose of this watch to showcase new technology. Were it a regular collection piece by Zenith, however, I would disagree with its inelegant design as I usually associate Zenith’s products with other characteristics. Concept watch design, however, is quite often by nature inelegant as it has a specific function to perform.

Truthfully, though, I was able to discern its Hublot origins immediately. Admittedly, this did disconcert my brand sensibilities somewhat.

The bulky case 44 mm in diameter and a sleeve-splitting 14.5 mm in height is made of the world’s lightest aluminum composite, which Zenith’s management – including new CEO Julien Tornare – has christened Aeronith.

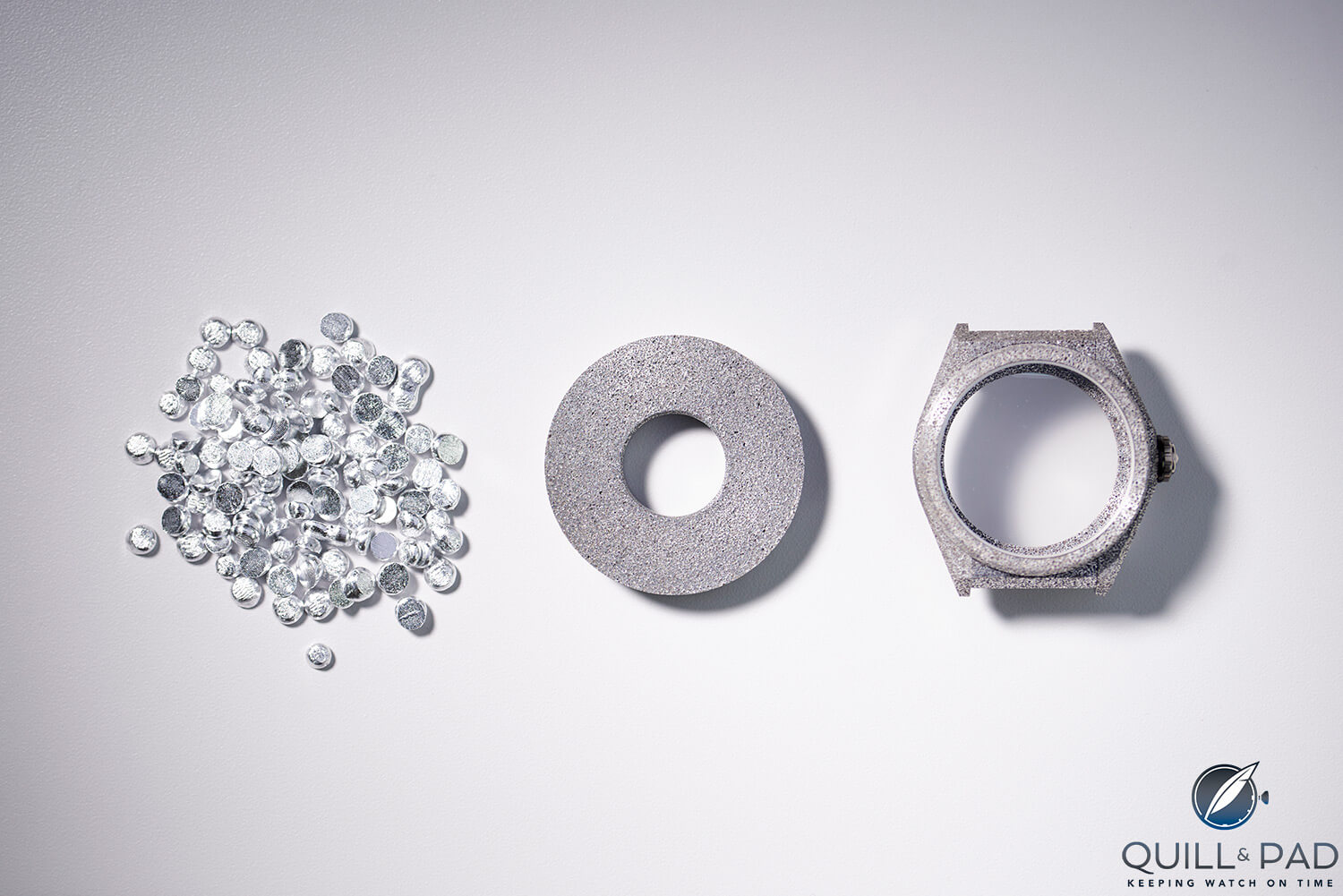

Zenith Defy Lab’s case (far right) and the aluminum and polymer ingredients that go into it

The case is made of a hybrid material combining aluminum foam and a special polymer (plastic) using a high-tech process that involves heating 6082 aluminum to its melting point and pouring it into a mold. Now transformed into an open-pore metal foam, the spaces thus created are filled with the anti-allergenic polymer. Hublot claims the machining is as easy as that of traditional precious metals.

With a density of 1.6 kg/dm3, it is 2.7 times lighter than titanium, 1.7 times lighter than pure aluminum, and 10 percent lighter than carbon fiber.

The first 10 pieces go to collectors

Ten pieces of this concept watch were created to mark the event, each of which was pre-sold to a collector as a special collectible version in 10 different colors (the collectors were each able to choose their colors).

The Zenith Defy Lab was introduced in a set of 10 unique pieces

It was offered in a gift box that included an invitation to the 2017 Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève (where this creation actually won the Innovation Prize), an invitation to the launch press conference at the factory in Le Locle, an invitation to visit the Zenith factory, and a tasting of Château d’Yquem Sauternes including the opening of a nineteenth-century bottle.

A handful of these ten collectors were present at the launch, and I had the opportunity to converse with a couple of them. What struck me was that although Biver stated during the live-transmitted press conference that these men would all be taking their new watches home with them, one of the collectors told me this was not true and that it would be at least a few weeks if not months before they would take possession of their new watches.

My information is that as of press time those watches have not yet been delivered.

Zenith Defy Lab

The future?

Biver and Sémon both commented that they are working on a new process to improve the manufacture of the compliant component and have promised that in 2018 a version of it will appear in a serial watch that is not silicon, “but a more industrial material.”

“We are at the beginning of this process, and there will be constant improvement,” Biver promised.

For more information, please visit www.zenith-watches.com/campaign/defy-lab.

Quick Facts Zenith Defy Lab concept watch

Case: 44 x 14.5 mm, Aeronith

Movement: automatic Zenith Caliber ZO 342 with monolithic silicon oscillator; 32.8 x 8.13 mm; 148 components including 18 jewels; 15 Hz/108,000 vph frequency, power reserve 60 hours; +/- 6 degrees amplitude

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds

Limitation: 10 unique pieces in a collector’s gift box, all pre-sold to 10 collectors before official launch

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

2 problems of course apply, as with all such innovations:- a) Where is the ‘soul’ of haute horlogerie in these oh-so-clever and oh-so-precise pieces of silicon; and b) What happens when the maker moves on (or goes belly-up) and you need a replacement! As a subset of (a), one might also mention that it is much more enjoyable/fascinating/instructive to watch a large, slow balance wheel than the frenetic contortions of these high-frequency items.

I often feel that these ultra-modern approaches rather miss the point of mechanical watches and, really, is there a need for more precision from mechanical watches: just get a quartz watch for that!

or get a smart watch… fully agree with you, my dear. On the other hand, for mass production, the “no need to assemble individual parts”, less machinery, smaller part numbers etc. should tone down the price quite a lot! However, as a limited edition scientific exercise for collectors, it is interesting.

Good points Ian, I think a depends on your perspective, I’m not sure how I feel about it – I haven’t experienced any of these silicon watches to give a comparison, although I’m leaning in your direction on this. On point a, the reason I love mechanical watches is they are miniature machines, with lots of moving parts. If these are replaced, what’s the difference between these silicon models and if we continue down this road, a smart watch? In terms of point b – another great point as all of these parts are proprietary and if the company goes belly up, the parts supply dries up. At least with vintage watches you can get someone to create a part that is within the tolerances that will get the watch working again. Not sure about these watches and they’re too expensive to throw away. It will be interesting to see how these watches will be accepted in the watch collector community in the long term.

Those are all very valid points, though I’d like to point out that Zenith is a traditional watchmaker with hundreds of years behind it already. I feel the chances of Zenith going belly up are slim. Also, Sémon and Biver said they aim to introduce versions of the compliant technology in traditional materials in 2018 (and Patek Philippe already has). But, absolutely, point taken with the parts supply where silicon is concerned!

I am actually with IanE on this a 100%, and though I find it fascinating, I believe should have been a Hublot creation. It`s very subjective of course, but me along with many others it seems (on the sales figures) match Zenith with tradition and quality, and have always steered clear of the Defy series.. I actually think it even looks quite good, but not for Zenith – where it is absolutely not recognizable as part of their strong range.

I welcome these innovations. It is still a mechanical device. I believe that Breguet (for example) would have used this technology if it were available to him. It doesn’t make sense to me to stifle technology because of traditional methods. I believe that watches need innovation to make them more appealing and to make collecting more interesting.

My question is the durability and robustness of these innovations. We learnt in school that no material is perfectly elastic, so these flexible/compliant components will lose accuracy over time – the question being how long that time is.

At the end of the article you state: in 2018 a version of it will appear in a serial watch that is not silicon, “but a more industrial material.” I take it you meant to say a serial watch that is not aeronith?

Thanks for reading, Jon. No, I was referring to the material of the compliant mechanism, not the case.

this is an excellent article. The Defy Lab was written about shortly after the Sept 2017 “introduction” but almost nothing since then. This article is the first to focus on “compliance” and the first to mention the obvious antecedent (PP Limited Ed Aquanaut). Until i read this piece, i believed that the Defy Lab would make its commercial introduction at Basel 2019, in about three weeks. And why now–10 of these had already been sold to collectors 18 months ago. But what i learned from reading here is that these 10 pieces were not taken home, by end of year had still not been sent the people who bought them. (I wonder if they are in possession of them now?) In other words, given the silence since Zenith since the 2017 announcement until now, perhaps 2019 Basel is too soon

It’s a good question. I do not know what Zenith plans to show in Basel, but I do know there is a big announcement on the way. Perhaps it is this…we’ll find out soon!