Jaquet Droz Signing Machine: Keeping Handwriting Alive, With A Machine

Handwriting is a disappearing art these days.

Not all schools today even offer courses in handwriting or cursive, as a majority of classwork is now done on personal laptops or school-provided tablets. Since tapping and typing have replaced manual notation, efficiency has steadily increased while information retention has steadily declined.

It turns out that writing something down by hand is one of the best ways to commit it to memory. This has to do with the fact that the physical action of writing out letters and words uses different systems of the brain than typing, leading to an increased use of different neural pathways – which strengthens short- and long-term memory retention.

Combine that with the fact that writing something by hand compared to typing it on a keyboard – like lecture notes, for example – forces you to consider, summarize, and understand something more completely due to the slower nature of taking the notes, increasing comprehension as well.

If that isn’t enough to encourage the continued use of handwriting and cursive instruction, how about the fact that nearly all historical documents use some form of handwriting script or extensively flourished cursive?

If the next generations aren’t taught to use handwriting, or at the very least how to read it, we risk having a significant majority of people unable to comprehend the documents that underpin modern society. The printed word is very important, but the written word is invaluable. Many texts from ancient times would be illegible to anyone only used to seeing fonts on a screen.

While I am fairly confident we are never likely to completely lose the ability to read our own handwritten history, it is a possibility – and one that shouldn’t be taken lightly.

In the most roundabout way, Jaquet Droz is subtly helping that with the official release of the Signing Machine.

Jaquet Droz Signing Machine

Inspired by the inventions of the company’s founder, Pierre Jaquet Droz, the Signing Machine is a complex set of gears that keeps handwriting alive, if only via an automaton.

Inspiration for the Signing Machine

Between 1768 and 1774, Pierre Jaquet-Droz created three of his most famous automatons: the Musician, the Draftsman, and, most famous of all, the Writer. These mechanical marvels, the highlights of an already impressive career, are some of the finest surviving automata examples in history (see Jaquet Droz’s Signing Machine: The Evolution Of Traditional Automata).

The Writer goes beyond the other two in that it doesn’t simply have a few set options, but is fully programmable via a 40-position program disk that allows for the change of letters, upper and lower case, and spaces. It writes on four separate lines.

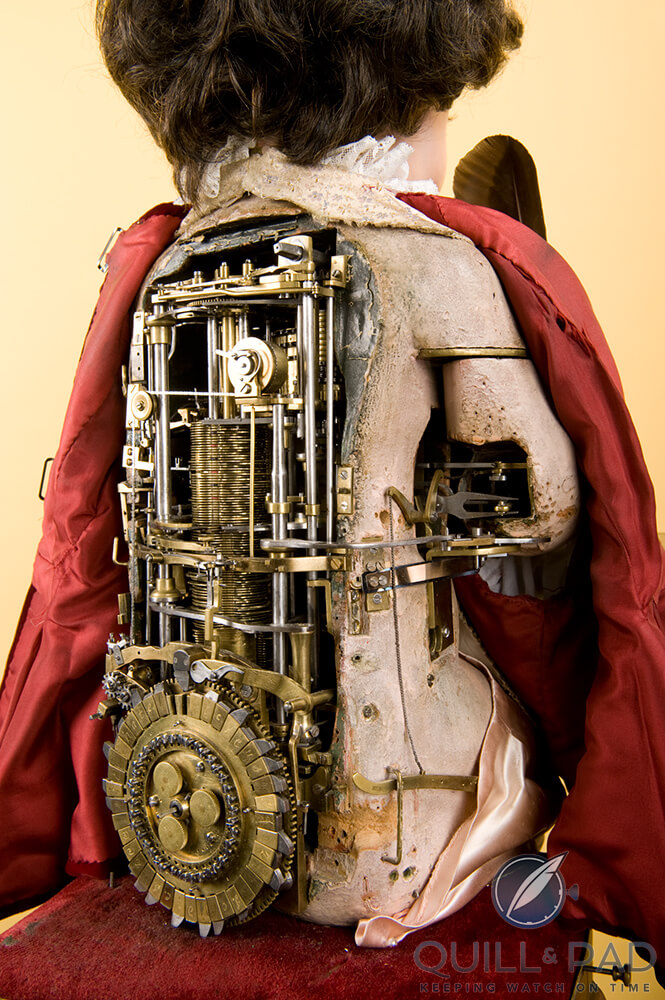

The Writer by Jaquet Droz

Each character began as a different height cam profile attached to the program disk that selected a vertical position for a massive stack of complex cam profiles mounted in the center of the automaton. This stack of disks has three different profiles to control each individual character, since the hand of the “writer” needs to move in the x, y, and z directions to create a fully formed letter.

The cams and mechanics inside The Writer

These profiles are “read” by three cam followers in the main mechanism, which translate the shape into motions that, when combined, create a complex geometric path that results in the quill drawing a letter on the paper.

The precision of this system was crucial to its success as even a slightly different cam profile would result in a squiggly line instead of a perfectly shaped letter G.

But interestingly enough, the trio of letter cam profiles was not the most impressive aspect of the Writer: it was the programmable disk. Having a mechanism that could create all of the possible paths needed for each character was a much more daunting task than hard coding in set paths to write a specific message.

That is why the Draftsman, which can draw beautiful pictures of a dog, a cherub riding a chariot drawn by a butterfly, and two versions of royal profiles, was a much simpler machine to build. Consisting of 2,000 components, the Draftsman was an incredibly complex machine in its own right, but it falls far short of the 6,000 components needed for the Writer.

The complex mechanics and system of cams responsible for the lifelike movements of The Writer

That number of components came from the need to have three cam profiles per each possible character (for x, y, and z movement), resulting in at least 78 character profiles just for the basic alphabet in lower case.

Add to that the upper case characters, any punctuation, spaces, or special characters and you are nearing 200 profiles to make up the functionality of the Writer mechanism. The Writer automaton is a masterpiece of mechanical engineering created in a time before calculators, CAD, and CNC machining.

In many circles, the Writer is considered one of the first programmable computers in history.

Big shoes to fill

That brings us back to the present day in which Jaquet Droz looked to its automaton past and decided to resurrect the Writer and interpret it for the modern era.

In 2010, a project was initiated to make a compact version of the Writer that would do one thing very well: produce a signature. After four years of development it was previewed in 2014, though it was clear that further development was needed (see Jaquet Droz’s Signing Machine: The Evolution Of Traditional Automata).

I still remember the buzz at Baselworld as visitors asked one other if they had already seen the Signing Machine, and of course the answer was often no as it was in high demand: there was only one prototype and it was rather finicky.

Personally, I only saw the renderings and perhaps less than a handful of actual photos of the prototype (as it was clearly a prototype lacking high-end finishing at the time), so I knew I was going to have to wait patiently for it to be officially released, in order to see it.

Four years later, in time for the 280th anniversary of Jaquet Droz, the Signing Machine was officially launched at Baselworld 2018, and all the excitement from 2014 came rushing back throughout the fair.

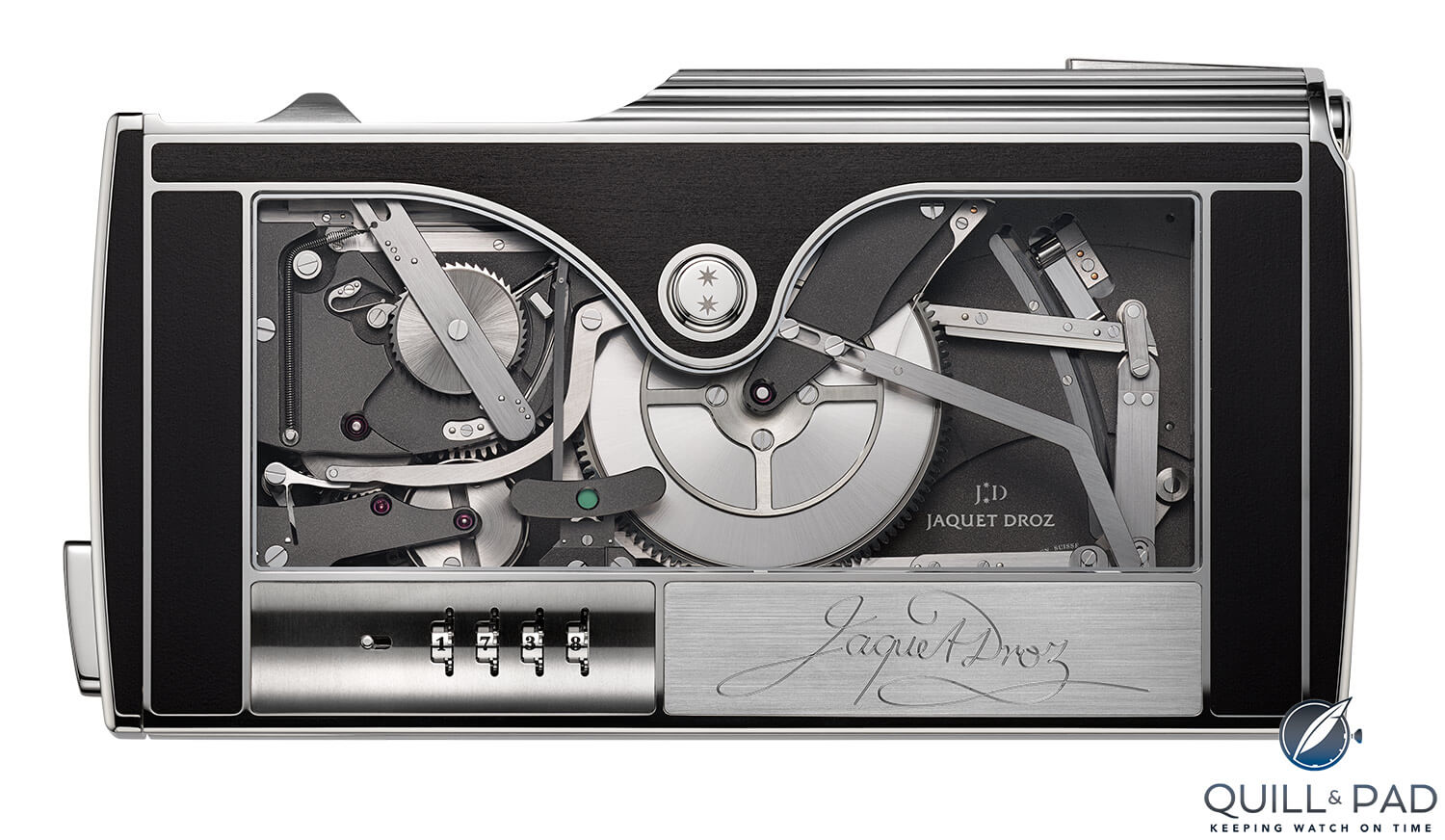

Jaquet Droz Signing Machine front and back

And I have to admit that the wait was definitely worth it. The eight years of development shows just how hard it was to construct something that smoothly translates cursive script into three directions of mechanical movement. It also shows how impressive Pierre Jaquet-Droz was to have created three much more complicated automata in only six years in the late 1700s.

The Jaquet Droz Signing Machine is definitely a worthy descendant of the Writer, however, as the script is perfectly formed from the smoothly gliding pen mechanically driven across the page.

It may not be ultimately programmable like the Writer, but the petite size of the machine combined with its mechanical prowess makes it a formidable engineering marvel. In a footprint of only 158 by 82 mm (6.22 x 3.22 inches), the Signing Machine flawlessly executes its programmed signature via three precisely shaped cam profiles inside the case.

How does the Signing Machine work exactly?

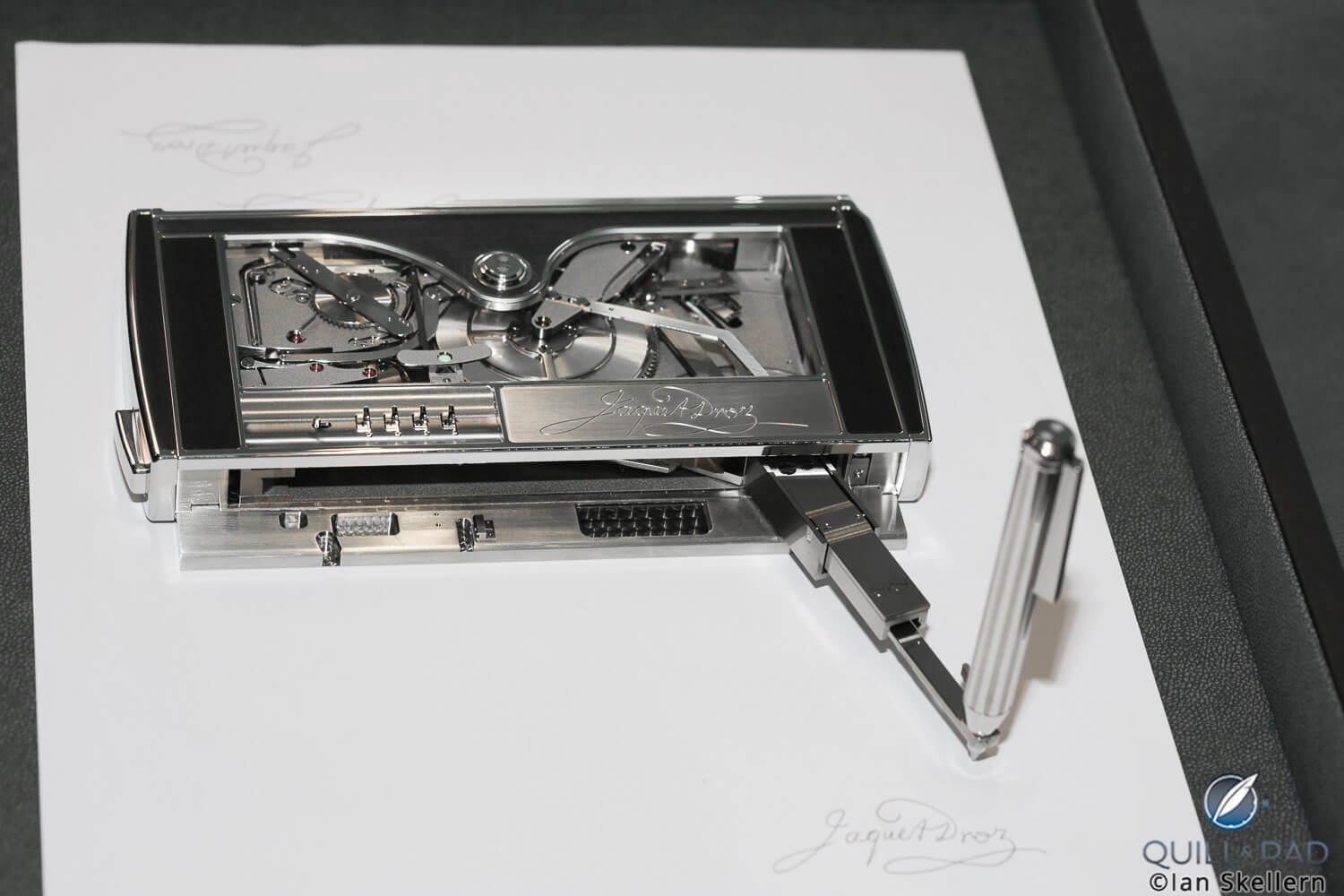

It all begins with winding the mechanism using the slider on the rear of the case. A few pushes is all it needs to fully wind the power reserve, and the mechanism is ready to provide two fresh signatures.

A four-digit code secures access to the operation of the Jaquet Droz Signing Machine

On the face of the Signing Machine is a four-digit code that allows the machine to be unlocked and opened via a button on the left side of the case. Activating the button sees a front panel flip open to reveal the writing arm. The arm is then pivoted manually into place before inserting the special pen that is concealed in the case next to the winding slide.

Once the Signing Machine is appropriately positioned on the item to be signed with the pen inserted in the holder, the start button on the face of the machine can be pressed. Once activated, the large mainspring barrel slowly rotates the main cam assembly thanks to a speed governor visible just above the locking code.

The cams and cam followers are underneath a large wheel driven off the mainspring barrel, but the control arms can be seen moving the writing arm left, right, in, and out to create a translated path in the shape of the signature.

Stylus of the Jaquet Droz Signing Machine

The writing mechanism is similar to a four-bar linkage that, as the name suggests, has four bars linked and pivoting together to translate movement in a relative way. The writing arm differs in that it uses one main control arm to initiate both the x-axis (in/out) and y-axis (left/right) moves via a sliding motion.

As the cam follower rides on one cam profile to drive the x-axis motion, a second profile is driving the y-axis as the writing arm slides along the length of the x-axis control arm. This sliding motion avoids a fixed pivot point between the two arms that would require a different type of movement from the cam followers.

Unlike a pantograph machine, which directly copies the motion of one end of a four-bar linkage to the other (one way that precise engraving and guilloche can be copied), the cam followers simply move up and down on the specially shaped cam, which necessitates the solution used for the Signing Machine.

But that isn’t all: the pen, while moving through the letters, needs to lift off the paper and reposition itself multiple times. This requires a third cam profile that does one simple thing: push an arm with a wedge forward to lift the arm slightly up at the extreme end. The simplest cam profile, this is the mechanism that allows the signature to have multiple beginnings and ends in one signature, crucial to clean writing.

All the little details of the Signing Machine

After the signature is completed, the pen lifts off the page and the writing arm retracts, ready to sign again. Even though the machine draws a fixed set of characters, the mechanism is still highly complex. Outside of the careful and precise shaping of the cam profiles, there are still 495 components that need to be perfectly made and finished to work together to create a beautiful signature.

There is even a power reserve indicator that uses an aperture to show either green or red, highlighting the need for winding.

Jaquet Droz Signing Machine

Given that it only will draw two signatures per winding I would assume that the power reserve indicator is a bit less crucial than one in a manually wound astronomical complication wristwatch. But adding one just in case shows the extent that Jaquet Droz goes to make sure something is engineered the best possible way.

This also shows with the design of the case and the mechanism compared to the earlier prototype. The final Signing Machine looks fully considered with a large viewing window for the mechanism and nicely finished insides.

The case has a very modern yet stylish design with a variation of textures. It can also be customized with jewels or engravings. A plaque showing the exact signature the machine pens is also included on the face of the case. The only downside for me is that, due to the layout of the mechanism, you can’t actually see the cam profiles and followers doing their thing.

But, given that this machine is perfectly replicating your signature via gears, cams, springs, and levers, I think I can forgive that one design direction.

All in all, the Signing Machine from Jaquet Droz is one of the coolest things to come out of Baselworld in a while. Eight years of hard work allows the world to finally enjoy a modern version of Pierre Jaquet-Droz’s original automaton.

And since the owner can have his or her own signature programmed into the cam profiles, even though it’s fixed, it still has some of the spirit of the programmable direction of the Writer.

I am personally looking forward to the next time I can see the Signing Machine again, though since they are made to order for each customer, it might be a while.

Jaquet Droz Signing Machine in its case

My biggest hope is that the idea will keep Jaquet Droz pushing forward to create more automaton machines that aren’t just for beauty, but also have some form of practical application. That is a form of steampunk that I can get behind.

And perhaps if people see a machine that can produce handwriting better than they can, it might inspire people to pick up a pen again and work on their own penmanship to keep the art alive.

Jaquet Droz Signing Machine

For more information, please visit www.jaquet-droz.com/en/news/the-signing-machine-jaquet-droz-the-art-mechanical-astonishment.

Quick Facts Jaquet Droz Signing Maching

Case: 158 x 82 mm, stainless steel and pear wood veneer, hand-engraved 18-karat gold

Movement: manual winding Jaquet Droz MAS

Functions: mechanical signature, power reserve, four-digit locking code

Limitation: custom made to order

Price: 350,000 to 480,000 Swiss francs

You might also enjoy Jaquet Droz’s Signing Machine: The Evolution Of Traditional Automata.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Dear team

I would like to order jaquet droz signing machine

Thanks

I would like to beythis machine

Price of this machine in INR

Price (at launch) is at the bottom of the article.

Regards, Ian