by GaryG

Those of you who have visited online watch forums with any frequency have very likely come across at least a few heated discussions of “finishing,” a topic that seems to fascinate, and divide, enthusiasts.

The temperature seems to go even higher when the discussion turns to “hand finishing.” Interpreted strictly, this is the art of shaping, beveling, striping, polishing, frosting, and applying other patterns to watch components using hand-driven tools alone.

What’s all the fuss about?

I have to confess that when I first started buying watches, the whole concept of “finishing” was completely unknown to me.

Like many people, my starting point for serious watches was with Jaeger-LeCoultre, a well-priced brand long known for its expertise in developing movements then, as now, justly viewed as offering good value for money – but not necessarily for high refinement of its movement finishing, at least on its less expensive pieces.

In those days, watches were all about functionality to me; when it came to cosmetics, the question I asked was simply, “Do I like the way it looks?” And it was actually several years before I bought a watch with what was then known as an exhibition case back, so I couldn’t have inspected the movement if I’d wanted to.

Heck, I didn’t even own a loupe!

Somehow, I seemed to get along just fine. Was I missing something important?

No, hand finishing doesn’t matter

Let’s start with a few of the “no” arguments:

· Fine hand finishing is a frill that doesn’t improve the operation of a watch. Done incorrectly, as when the teeth of gears are over-polished, it can actually destroy performance.

· Many perfectly fine – even great – watches like Rolex and Omega, both known for their excellent timekeeping, take a function-first, industrial view of finishing.

· Machine finishing techniques are often so good that they are entirely sufficient, even for buyers who place high value on the cosmetics of a watch and its movement.

· Even seasoned collectors can’t seem to agree on precisely what “fine hand finishing” is.

That last point is worth a moment to discuss. Consider the touret, a small, hand-held motorized tool (it looks a bit like an electric toothbrush) that can be used to bevel and polish the edges of the plates and bridges in a watch movement.

If you visit some of the watch manufactures most famous for finishing quality, you will see many workers using tourets rather than files. Hand finishing, or not?

There’s even conflict about what the output of hand finishing should look like. Roger Smith – an independent watchmaker whose watches I covet dearly – uses a finishing style characterized by sharp edges, simple shapes, and obvious markings and irregularities from handwork.

Among collectors, there’s great dispute about whether his style is best-described as “classic English” or “rustic.” For the record, I am more in the latter camp, but I do respect the stylistic choices that Roger has made.

Yes, hand finishing matters

Before getting to my other personal views, let’s turn the coin over for a second and look at some of the most frequent “yes” arguments for hand finishing:

· Many finishing techniques have strong technical foundations; for instance, the use of perlage (those circular swirls) and applied stripes to catch and hold stray particles and grimy oils so that they don’t get between moving parts.

· At its highest level, hand finishing is an art. Its results, whether seen with the naked eye, loupe, or macro lens, have a visual impact and warmth that machine-finished pieces (and even less-distinguished hand-done pieces) lack.

· Beautiful finishing, done by hand, links modern horology to the finest watches of the past. The decorative arts are not recent inventions and it would be a shame to lose them with the passage of time.

One collector’s view

So where do I come down on the Great Hand Finishing Debate?

For me, there is one super ordinate rule: the finishing work done, and its results, should be appropriate to the watch at hand. That may sound pretty mushy, so let’s break it down more specifically:

· Is the result coherent? That is, is there a sense of things fitting together into a unified presentation? For instance, one really nice bit of finishing (say, a hand-engraved brand logo on a movement plate) can be jarring if it is surrounded by laser-cut or stamped markings that are clearly at another level.

· Does the appearance of the watch match the task to which it is to be put? No use spending hundreds of hours beveling the bridges on a tool watch, in my view.

· Are the level and type of finishing clearly associated with the brand’s personality and promise? Here, I think of the A. Lange & Söhne Lange 1; I would characterize its finishing as fairly assertive, and the company uses both fully manual finishing techniques and tools like the touret as it thinks makes most sense. To me, the resulting sense conveyed by the watch is both precise and masculine; very much in keeping with how I think of A. Lange & Söhne as a brand.

In other cases, really refined finishing is a big part of what a brand or maker stands for in the first place. Kari Voutilainen’s initial rise was largely based on his sublime finishing of “new old stock” vintage ébauches such as the Peseux 260 used in his Observatoire.

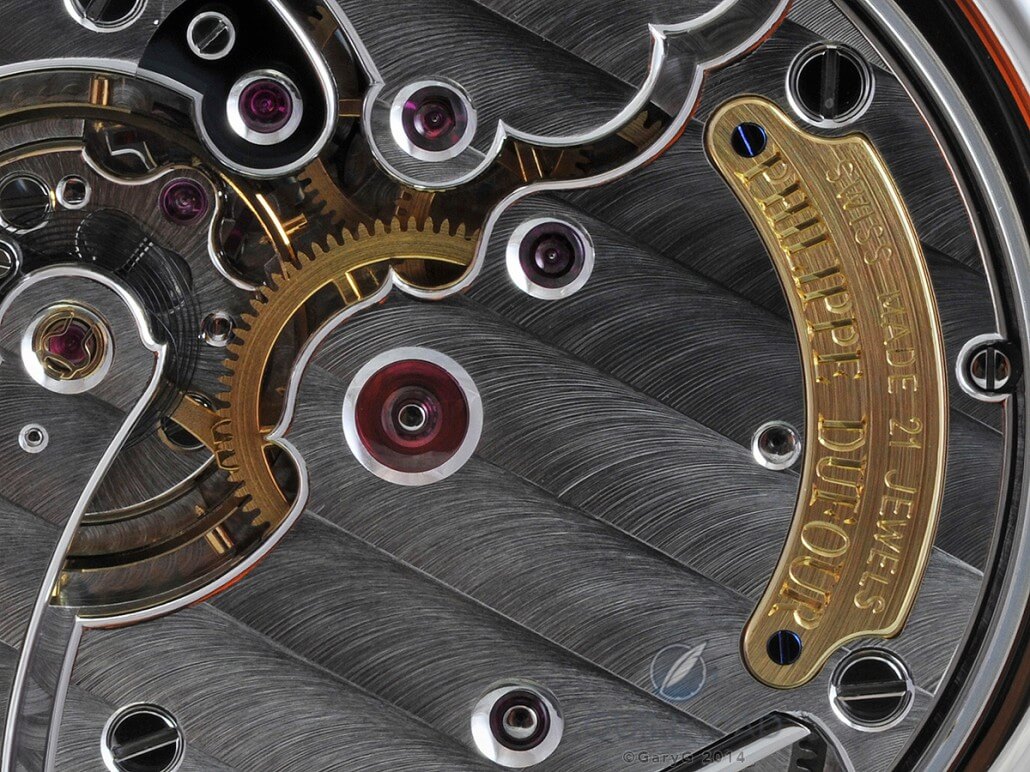

And Philippe Dufour’s mastery and application of the traditional hand-finishing arts is the thing that makes his three-handed Simplicity one of the most prized watches in the world, not revolutionary movement geometry or unique case or dial designs. I could go on for a long time about the technical finishing merits of what you see in the Simplicity movement image below, but I think I’ll just let you soak it in.

For the makers who operate at the very top of the pyramid of hand finishing, part of the game is that they do things that are really, really hard. Kari made each of the hands for each Voutilainen Observatoire personally, and it took him a full day’s finishing work, per hand, to achieve the level of symmetry and polish on display.

On both Kari and Philippe’s watches, there are cues on the movement side that the finishing has been done the old-fashioned way, with tiny hand files and wooden pegs. Sharp interior angles cannot be finished by machine or touret, and the characteristic “horns” of Philippe’s movement designs both clearly identify the watch as his and at the same time provide an opportunity to show off just a little bit.

One brand that has set the bar very high with regard to both technical innovation and finishing quality is Greubel Forsey. One example: do you see the black tourbillon bridge that stretches across the photo above?

It’s not black – rather, it’s finished with a technique often called black polishing: laboriously hand-smoothing a piece of steel until it is so perfectly flat that from most angles it appears to be a deep, black pool, and from straight-on reveals itself as a perfect mirror.

This particular watch, the Greubel Forsey Invention Piece 1, also is (to me, at least) a good example of another axiom: truly great finishing depends on conception as much as it does on execution.

My watch buddies and I disagree from time to time on the quality of finishing on particular watches. When this happens, more often than not they are focusing on the technical quality of the work (for instance, that the Geneva stripes are uniform and stop smoothly at the beginning of the beveled edge of the plate) and I’m looking at the overall effect (for instance, are there multiple patterns or techniques used in a small space that don’t seem to work together?).

To me, the dial side of the Invention Piece 1 is a great example of coherent (that word again) conception that applies multiple finishing techniques.

The background frosting of the main dial, in addition to being much harder to do than you’d think, provides a luminous palette for the matte rings surrounding the time-keeping indications.

Within the two-dimensional tourbillon itself, the polished bridges, escape wheel, and edge of the balance wheel play in the light without being overwhelming, while the supporting surfaces are either brushed or frosted to be visible without being blingy.

The anodized colors of the triangular hour and minute hands make them nicely visible and provide a bit of a technical touch, while the blued second and power reserve hands with black-polished center discs are suitable to their purpose and allow us to appreciate yet another finishing technique in an appropriate context.

So what is great finishing?

“We know it when we see it,” said U.S. Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart on the definition of pornography in 1963.

Sometimes, when watch nuts talk about great finishing they use the term “the glow.” As with the subject of Justice Stewart’s famous observation, it’s hard to specify. But when you’ve studied enough examples, really fabulous handwork does begin to impart both visual and emotional impact.

The happy news is that great finishing is where you find it; while many people seem to think primarily about movement components when they talk about finishing, I happily include components such as hands, dials, and even cases, an area in which Vianney Halter’s watches excel.

At the end of the day, it may have turned out that I wasn’t so wrong in the first place. “Do I like the way it looks?” is actually not such a bad criterion for judging the quality of finishing.

As with other visual arts, however, an understanding of technique both enriches and changes one’s perception of “what looks good.”

The next time you look at a watch with your naked eye or through the loupe, try to apply the tests of coherence, suitability, and brand personality to what you see. If you’re intrigued, learn more about “what’s really hard” about many aspects of hand finishing and always look for “the glow.”

Chances are you’ll find your own appreciation for this difficult, and meaningful, element of watchmaking.

* This article was first published on December 17, 2014 at Does Hand Finishing Matter? A Collector’s View Of Movement Decoration.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Gary, wonderful essay. I think watch finishing on the whole I’d badly misunderstood. Too often flash is confused with real hand work. Nowhere is the confusion greater than in the evaluation of anglage. Traditional anglage is done by hand with a series of files, followed by wood polishing. Industrial anglage is done with a touret. A touret looks like an electric toothbrush. I search for sharp interior angles or sharp exterior angles to determine which method was used. Sharp interior or exterior angles can only be done with the traditional file method. When you look at the photo of Kari’s Observatoire and Dufour’s Simplicity and on the skeleton Breguet you can see plainly that wondeful file/wood anglage was done. On the other hand, on many revered Geneva brand watches (guess which) and other equally estimed brands that there are zero sharp interior or exterior angles…..for a reason. They are done with the electric toothbrush. Sadly the vast majority of collectors don’t distinguish between the methods and don’t know the huge difference when they sing the praises of the finishes done industrially.

I began collection as you author did. Early on I purchased a few JLC because of the lure of in house movements that looked (nice) under an exhibition back. As I learned about what “real collectors” collect, I migrated to Vacheron & Patek.

I’m now ready to sell the later brands, as I’m tired of seeing the same movements used in so many models, and though adequately finished, nothing really extraordinary.

I may sell 25-30 watches and may just purchase one GF, Roger Smith, or Dufour.

Good luck, please let us know what you decide to do!