by Martin Green

In this, the first of a series of four articles, I will look into the impact and influence that Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747–1823) and the eponymous brand bearing his name has had on events that changed the world – during and even far beyond the watchmaker’s lifetime.

While Breguet dedicated his life to making timekeeping as precise as possible, his creations unintentionally ended up playing pivotal roles in some of the darkest of times of humankind. Hence the name of this series: “The Battles Of Breguet.”

In this first installment, I look at how one of the earliest battles was as much a personal one for Abraham-Louis Breguet as it aided the position of the French kingdom he served – because the quest to dominate the seas started with a quest for precision under the most difficult circumstances.

The importance of precision timekeeping at sea

Before venturing into Breguet’s contribution to conquering the seas, let us first focus on why precision timekeeping is essential to navigating them. In the mid-1600s for many, if not most, sea-faring western European countries, economic prosperity depended on international trade (as it still does).

And in a pre-aviation, pre-train, and pre-automobile era, the majority of goods traveled by sea. The prosperity of many nations depended on having safe and secure trade routes for their ships to sail (at least partially) around the world.

France, Great Britain, Portugal, Spain, and the Netherlands evolved into the largest seafaring nations, and some would eventually command overseas territories on the other side of the world several times larger than their homelands.

But to dominate the seas you needed to be able to safely navigate them, and at this time determining longitude at sea was more art than science with often tragically fatal results (see the Scilly naval disaster of 1707).

Even the most precise map is worthless if you don’t know where you are. While on land, or at least when land is visible from the sea, distinct landscape features can be looked up on a map to determine approximate position. But such a luxury doesn’t exist on the high seas.

To determine position one must know both latitude (north-south position) and longitude (east-west position). Measuring latitude was never much of a problem, as the sun by day and the stars by night allowed navigators to make a precise enough calculation. But determining longitude was a different thing.

Earlier in history, it was known that longitude could be established if you knew the difference in time between your current position and a reference point. Again, the sun and the stars could be used to determine the local time, but how could you possibly know the correct time at the reference point?

While there were clocks and pocket watches readily available during the late 1600s, none of them were anywhere close to being precise enough, let alone reliable enough, for even reasonably accurate navigation.

Reliably correct time in the hostile enviroment of a sailing ship at sea for months or years wasn’t just a difficult problem to solve, it was thought by many of the brightest scientific minds of the time that marine navigation would be eventually mastered by astronomical means rather than clockwork.

It wasn’t until John Harrison completed his H1 marine timekeeper in 1735 that significant progress was made.

However, it wasn’t until Harrison’s H4 was first tested in 1759 – a timepiece that looked much like an oversized pocket watch – that precision, durability, and manageability reached the level of solving the longitude problem in both a technical and practical sense.

Derek Pratt’s reproduction of John Harrison’s H4 (photo courtesy Horological Journal)

Created specifically for precise navigational timing at sea, Harrision’s H4 launched a new genre of timekeeper, the marine chronometer. While Harrison’s design was outstanding, it was too complicated and expensive to make.

Thomas Earnshaw and John Arnold took Harrison’s design and improved it. The result was what would become the standard marine chronometers that would be in use for the next 200 years.

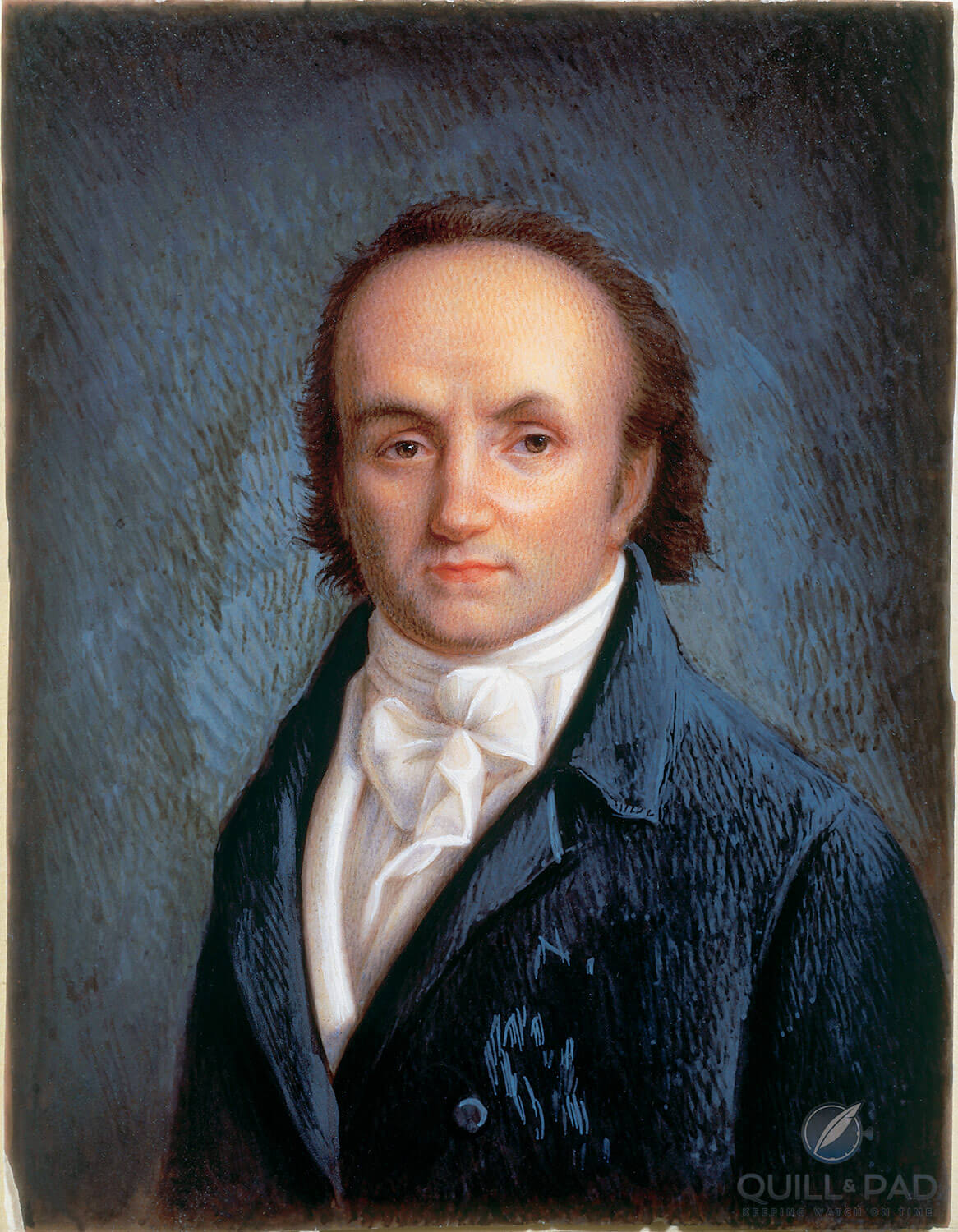

Portrait of Abraham-Louis Breguet

Abraham-Louis Breguet: by royal appointment

Breguet wasn’t born until 1747 so did not contribute to the initial horological solution for the longitude problem, but that didn’t stop him from playing an important role as the importance of the marine chronometer continued to increase well after it was invented – translating higher precision directly into more precise navigation.

To put this into today’s terms: imagine trying to navigate through a city (or sail through a reef) if your phone’s GPS was accurate to a kilometer rather than a few meters. GPS precision thanks the precision of atomic clocks.

Empires rose and fell due to marine chronometer technology; indeed, there was a great hororlogical rivalry between the large European seafaring nations.

Then came French watchmaker Ferdinand Berthoud with his first marine timekeeper in 1761. Just like Harrison, Berthoud went through a sharp learning curve and continued to refine his designs, making them more precise with every new version. In 1770 the king of France made Berthoud the very first official Horloger de la Marine, the watchmaker responsible for supplying the French Royal Navy with marine chronometers. It was an appointment only the French monarch was allowed to make.

The second watchmaker to be appointed to the position of Horloger de la Marine, was Ferdinand’s nephew and protégé, Louis Berthoud.

Then in 1815, King Louis XVIII appointed an new Horloger de la Marine: Abraham-Louis Breguet.

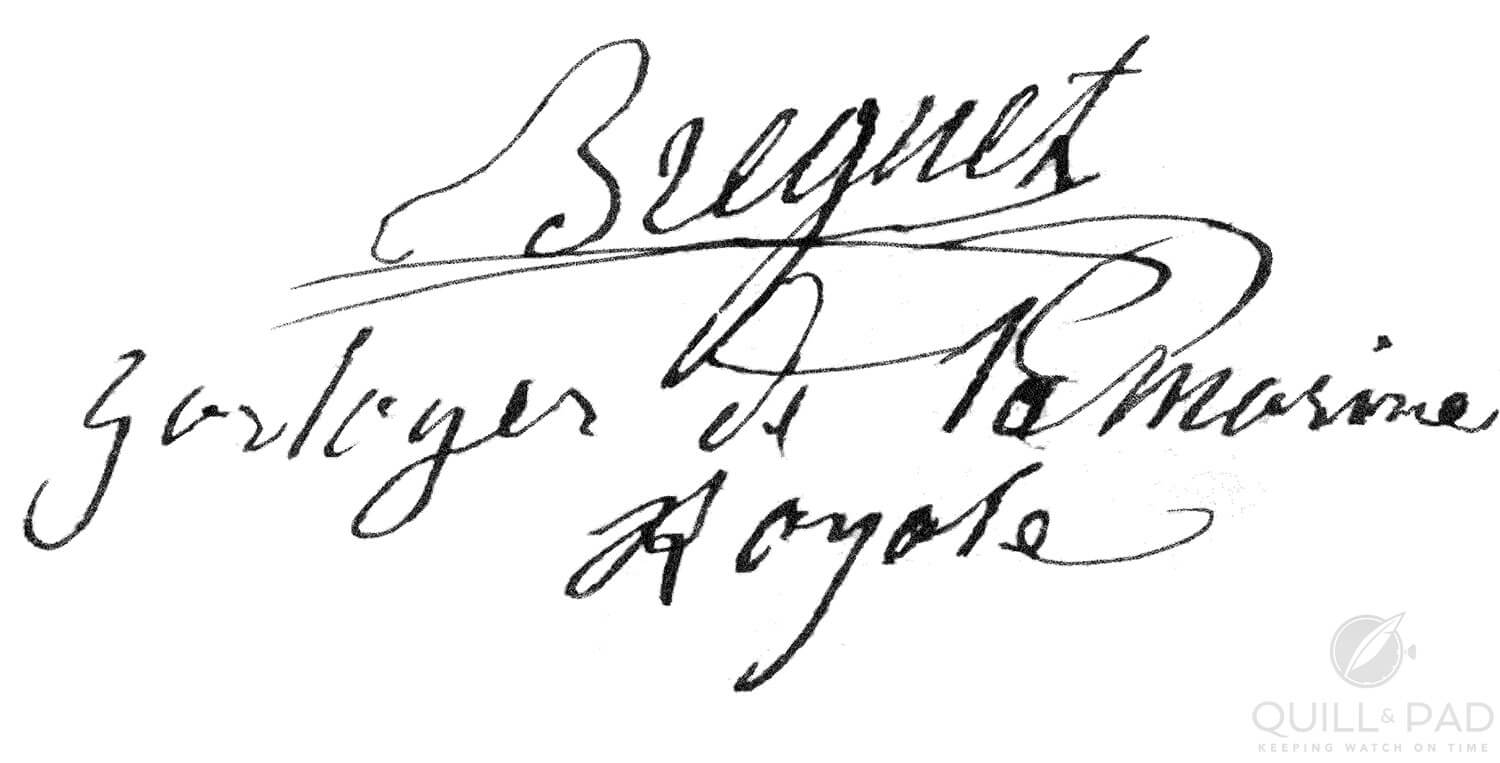

Abraham-Louis Breguet’s signature as Horloger de la Marine (by Royal Appointment)

It’s ironic then that, unlike the Berthouds, Breguet had never really made marine chronometers. This says a lot about the quality of his work for regular clients: his reputation was such that he was entrusted with a critical appointment about which it’s no exaggeration to say that because of the importance of sea-borne trade, the future of the entire nation depended on accurate navigation and defense depended on having the ability to navigate at least as precisely as one’s foes.

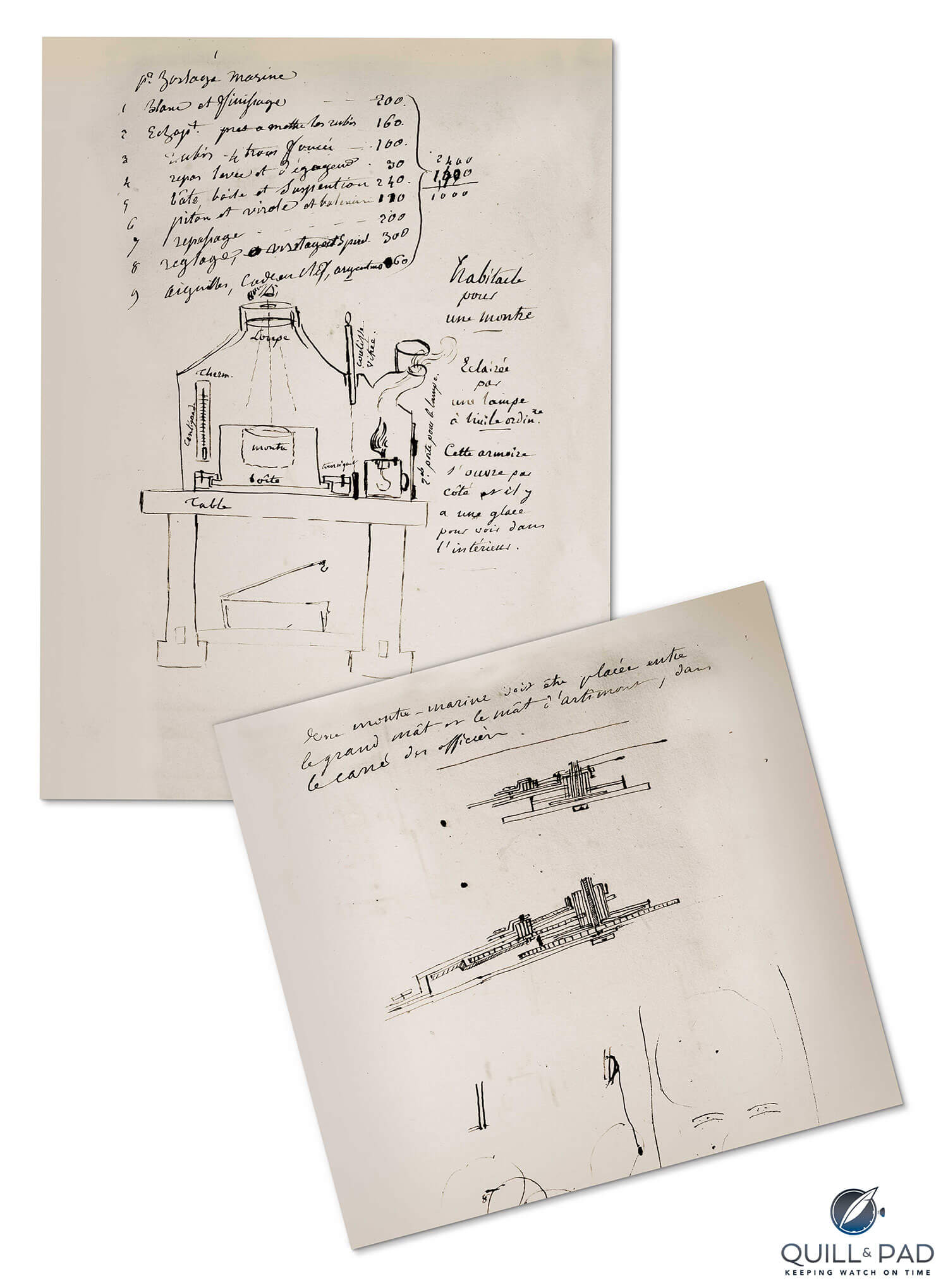

After Breguet’s appointment as Horloger de la Marine, he went to work with his usual vigor, focusing both on perfecting the technical aspects of the marine chronometer and also keeping the human factor in mind.

Breguet knew that the people who depended on his timekeepers at sea were not watchmakers, but rather captains and officers of His Majesty’s navy. And while they may have been skilled in all aspects concerning ships and ocean warfare, they were likely to be less skilled in operating clocks.

Abraham-Louis Breguet Marine Chronometer No. 3196, which was sold to the French navy in 1822

To improve horological knowledge in the navy, in 1817 Breguet published Instructions sure l’usage des Montres Marines, a 23-page instruction booklet that explained how to check and operate Breguet marine chronometers.

Sketches by Abraham-Louis Breguet illustrating the installation of a marine chronometer aboard a ship

That Breguet’s marine chronometers were superlative becomes obvious from an order placed in 1820 for one by the British Board of Longitude.

Even after Breguet’s death in 1823, his son continued making marine chronometers as did Breguet as a firm until the 1960s, after which these mechanical clocks were surpassed in precision by new technologies.

Abraham-Louis Breguet Marine Chronometer No. 3196 sold in 1822 to the French navy

Seaworthy Breguets today

As Breguet has such a long history in marine chronometers, it was only a matter of time until they served as inspiration for a wristwatch, which came about in 1990 when the first Marine collection was launched.

Back then the Breguet Marine was very modest, comprising only two automatic time-only models, but later on more complicated pieces were added, most notably the Hora Mundi, a charming world time watch.

Breguet Reference 5817 from Breguet’s second Marine collection

In 2005 the first Marine collection was replaced by the second: times had changed, and Breguet was now not only part of the Swatch Group, but also considered the crown jewel by the group’s co-founder and CEO Nicolas G. Hayek.

The second generation of the Marine collection also launched with an automatic watch, however Reference 5817 was much sportier than its predecessor in terms of design.

And a child of its era, the second generation Marine featured a large date.

This time-only Marine was joined by more complicated versions including chronograph, an alarm, and a second time zone. The top model even combined a tourbillon with a chronograph.

Breguet Marine Équation Marchante Reference 5887 in platinum

In 2017 Breguet was already hinting that another change was in the air: the Marine Équation Marchante Reference 5887, which combines a tourbillon, perpetual calendar and equation of time, was the talk of Baselworld 2017. It also boasted an updated case and dial design.

Breguet Marine Alarme Musicale Reference 5547 in pink gold

In 2018 a time-only model, a chronograph, and a musical alarm watch joined the third generation of the Marine collection (see New Breguet Marine Models: All Hands To Battle Stations!).

So while marine chronometers are no longer part of Breguet’s current collection, the spirit of their heritage lives on at the modern company on the wrist.

Those who would like to see one of Breguet’s original marine chronometers might consider visiting the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. This museum boasts ownership of a Breguet marine chronometer in one of the chronometer rooms where it used to test the precision of chronometers before they were sent out to “active duty.” Do check first though as the museum has so many different marine chronometers that it may change the displays.

A visit to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich also offers the opportunity to see some of John Harrison’s original marine timekeepers. And, of course, to stand on the Prime Meridian.

For more information on the Breguet Marine collection, please visit www.breguet.com.

Quick Facts Breguet Marine Équation Marchante Reference 5887

Case: 43.9 mm, platinum or pink gold

Movement: automatic Caliber 581DPE with 60-second tourbillon

Functions: hours, minutes; running equation of time, perpetual calendar, power reserve indication

Price: $230,400 in platinum, $215,000 in pink gold

Quick Facts Breguet Marine Reference 5517

Case: 40 mm, white gold, titanium, or pink gold

Movement: automatic Caliber 777A, 55-hour power reserve; lever escapement with silicon pallet fork and balance spring, frequency 4 Hz/28,800 vph

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; date

Price: $28,700 (pink and white gold), $18,500 (titanium)

Quick Facts Breguet Marine Chronographe Reference 5527

Case: 42.3 mm, white gold, titanium, or pink gold

Movement: automatic Caliber 582QA, 48-hour power reserve; lever escapement with silicon pallet fork and balance spring, frequency 4 Hz/28,800 vph

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; date, chronograph

Price: $33,880 (pink and white gold), $22,600 (titanium)

Quick Facts Breguet Marine Alarme Musicale Reference 5547

Case: 40 mm, white gold, titanium, or pink gold

Movement: automatic Caliber 519F/1, 45-hour power reserve; lever escapement with silicon pallet fork and balance spring, frequency 4 Hz/28,800 vph

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; date, second time zone, alarm, alarm power-reserve indicator, alarm on/off indicator

Price: $40,900 (pink and white gold), $28,600 (titanium)

You may also enjoy:

Breguet Marine Équation Marchante Reference 5887: Equating Time On The Run

Breguet Marine Alarme Musicale 5547: Keeping Technological Traditions Alive

New Breguet Marine Models: All Hands To Battle Stations!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!