I had never really paid much attention to opals before, but upon closer inspection I realized this gemstone is extraordinary – shrouded in mystery and well worth learning more about. Looking at an opal is like looking at fireworks or even looking into a galaxy.

The reason I took a closer look at opals at all is because of something my mother recently said as we were traveling to her hometown. She was telling me about a particularly interesting superstition surrounding the opal that she remembered her grandmother telling her: she related that my great-grandmother considered it unlucky for anyone not born in October to wear opals; the opal is October’s birthstone. And while this might seem irrelevant right now, it won’t once you finish reading this section: my great-grandmother was born in October 1909 in Scotland.

Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Tourbillon Opal

So I did a little research on the topic as both of us had wondered where such an unlikely urban legend might come from, particularly from a woman who was as no-nonsense as Nana.

Surprisingly, I found that this superstition finds its roots in Sir Walter Scott’s Anne of Geierstein or The Maiden of the Mist, published in 1829. In the novel largely set in Switzerland – which my great-grandmother had undoubtedly read in her youth as Scott is a Scottish national treasure – an opal was said to have lost its color after holy water was dropped on it and that lead to one of the character’s deaths.

Scott wrote, “The opal, on which one of these had lighted, shot out a brilliant spark like a falling star, and became the instant afterwards lightless and colorless as a common pebble, while the beautiful Baroness sunk on the floor of the chapel with a deep sigh of pain.” Earlier in the novel, the opal is described as a thing of mystery, described as “red like the spark of a fire.”

The novel was very popular in its day, though probably not with jewelers selling the semi-precious stone as within a year after publication, opal sales declined by about 50 percent and did not rise again for several years.

Interestingly, though, in the Middle Ages, opals were actually considered beacons of good luck because of their vibrant spectrum of colors and the uniqueness of no two stones looking alike.

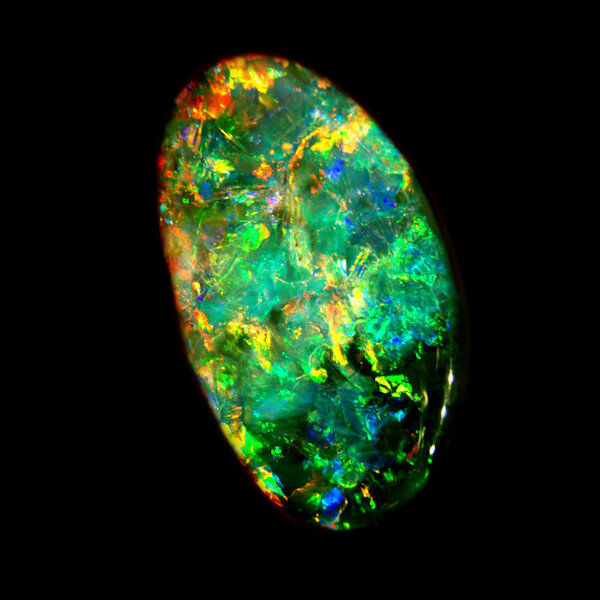

20.05-carat Ethiopian Welo opal set in gold and surrounded by diamonds (photo courtesy Doxymo/Wikipedia)

It was also believed that opals could provide invisibility if wrapped in a bay leaf and held in the hand.

Every opal is different

Natural opals can be categorized in a number of ways that take chemical composition, color, and transparency into consideration, but three common types are: precious opals, common opals, and fire opals.

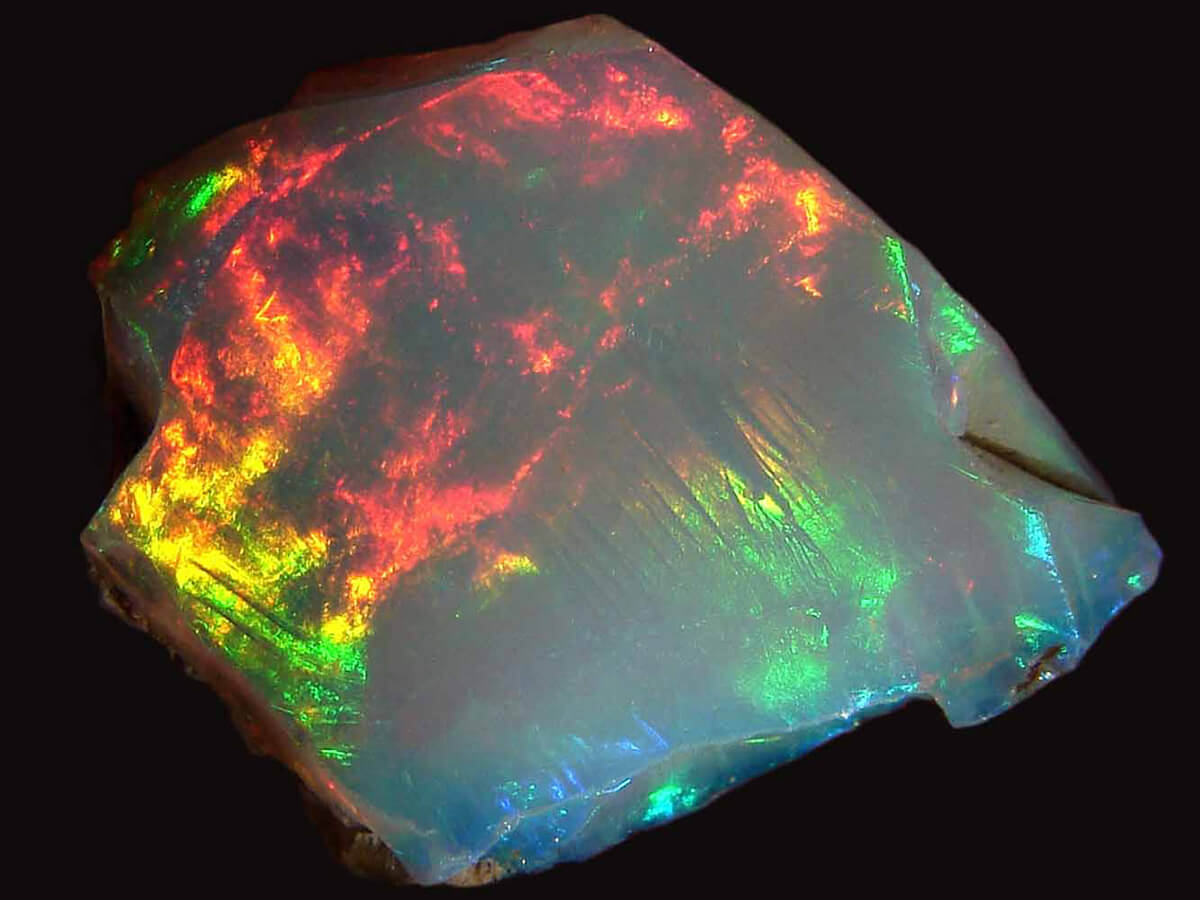

Uncut precious opal from Ethiopia (photo courtesy www.mineraltivadar.hu)

Precious opals boast an amazing interplay of colors, creating a beautiful shiny and shimmery effect.

Common opals (photo courtesy www.wy-opal.blogspot.ch)

Common (white) opals tend to be opaque and milky in their iridescence as compared to their rainbow-hued cousins, but these can be absolutely beautiful in their tone-in-tone shades. The term for the shimmering lack of color play exhibited by white opals is opalescence.

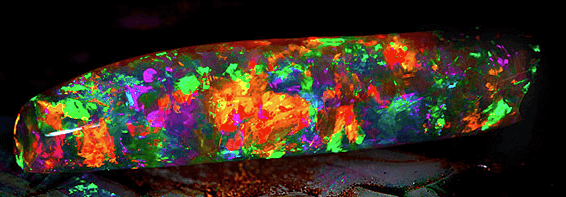

A fire opal, the Virgin Rainbow is billed as the finest opal ever found (photo courtesy South Australian Museum)

The third most common type of opal is the fire opal, which typically comes in the warm color scheme of yellow, orange, and red. Occasionally, these can exhibit flashes of green.

The vast majority, around 97 percent, of gemstone-quality opals are found in Australia, with the state of South Australia alone supplying a whopping 80 percent of the world’s supply of opals.

Recently, though, more and more opal production has shifted to Ethiopia, with the first published report of a genuine gemstone in the country appearing in 1994. Common opal comes from a variety of different places, with some pink shades sourced in Peru, while other kinds of common and opaque opals have been found in U.S. states like Idaho. Fire opals are found almost exclusively in Mexico; these are known as the Cantera opal.

Notable Australian opals

The Olympic Australis is the most valuable and largest opal ever found. The 17,000-carat specimen was discovered 10 meters under the ground by a miner in 1956 in the Eight Mile opal field. Particularly interesting is that the gem is named after the Olympic Games, which were held in Melbourne that year; it is valued at AUD$2.5 million.

The Olympic Australis: at AUD$2.5 million it’s the world’s most valuable opal

Australia is also the source country for the opals used in two of Jaquet Droz’s latest unique pieces, though these are priced quite a bit more affordably than $2.5 million.

Jaquet Droz

Jaquet Droz is a specialist in using unusual and unique materials for its dials and has over the years most likely used every rare stone available to embellish its limited and unique editions.

The opal is a particularly good choice as a dial because of its eye-catching luminosity and shimmering colors. But, like any of the other rare materials, it’s not that easy to cut to size.

Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Tourbillon Opal

First, the dial maker must choose the part of the stone that makes for the most beautiful dial. Then it must be cut and ground to the approximate shape in a rather step time-consuming step. After that, the stone is cemented to a work plate made of brass and ground flat, also a tedious process as tolerances must be precise. Then it is machined to the exact thickness – generally no more than 0.4 mm.

After all that, the opal is carefully drilled using an ultrasound drilling machine and polished. These precious dials are particularly fragile and hard to work with, so the final step – adding the applications – can be harrowing.

The Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Tourbillon

The Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Tourbillon was introduced in late 2011 and its movement is based upon Blancpain Caliber 25, which stands to reason as the movements of the two Swatch Group siblings both come from Blancpain Manufacture (formerly Frédéric Piguet).

Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Tourbillon Opal

It’s worth briefly going into the tourbillon assembly because that’s quite interesting in itself.

The design of this tourbillon originates in the non-concentric style of tourbillon that Blancpain introduced in 1989. It was developed for Blancpain (and Swatch Group) by A.H.C.I. co-founder Vincent Calabrese. This eccentric-axial tourbillon, which the French have dubbed a “carroussel” (though it has no similarity to Bahne Bonniksen’s karussel construct), has one significant advantage over standard tourbillons in that it can be used to make flatter, thinner, more elegant watches.

Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Tourbillon Opal

The non-concentric flying tourbillon has been made visually even lighter and airier here by adding a sapphire crystal tourbillon bridge, and, of course, the Swatch Group’s now-ubiquitous silicon balance spring has been added to the automatic tourbillon movement.

For more information, please visit www.jaquet-droz.com.

Quick Facts Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Tourbillon Opal

Case: 39 x 11.52 mm, red gold or white gold set with 350 brilliant-cut diamonds (1.76 ct)

Dial: Australian opal

Movement: automatic Caliber 25JD.Si with silicon balance spring and pallet lever, flying one-minute tourbillon with sapphire crystal tourbillon bridge, seven-day power reserve

Functions: hours, minutes, subsidiary seconds

Limitation: one piece each in red gold and white gold, available only in Tourbillon and Jaquet Droz boutiques

Price: 128,500 Swiss francs each

Piaget and opals

Piaget has a long history using precious and semi-precious gemstones in its watches and jewelry, many of which originate in creations made for the jet set in the 1960s and ҆70s.

The 1960s were a hip time, and the world of celebrities was beginning to really convey fashion messages to societies now widely equipped with television. In 1964, after establishing a distinct reputation in the world of the rich and famous as a jeweler-watchmaker, Piaget came out with something inspired: watch dials in a veritable rainbow of colors made of coral, lapis lazuli, jade, malachite, opal, onyx, turquoise, and tiger’s eye.

Piaget Sunny Side of Life Infinite Reflections secret sautoir watch

No one had ever seen anything like it and they were all unique watches – each one a collector’s item – since each stone looked very different thanks to specific hues, inclusions, and colors. In an era marked by an explosion of color and shape, the cuff watches proved particularly popular with women.

In 2014, Piaget celebrated its 140th anniversary and on the occasion of the 27th Antique Dealers Biennial, the brand highlighted its creative history from the 1960s and ‘70s, a period enhanced by the most precious materials and color.

Piaget’s 2014 white gold opal cuff watch snow set with 1,699 brilliant-cut diamonds

And in doing so Piaget recreated a 1971 white gold opal cuff watch and snow set it with 1,699 brilliant-cut diamonds (approx. 20.50 ct). The natural blue opal dial is a different shape than the original, which was decidedly oval, most likely dictated by the cut of the stone used. The modern cuff watch, powered by the Piaget 56P quartz movement, needed 10 days alone for snow setting the diamonds.

Sunny Side of Life

The opal returned in Piaget’s 2016 Sunny Side of Life collection of 150 pieces of high jewelry and unique watches (see Piaget’s Sunny Side of Life: A Radiant Collection Of Rare Haute Horlogerie And High Jewelry).

The unique piece 18-carat white gold Piaget Sunny Side of Life Infinite Reflections secret sautoir watch (Reference G0A41250) is set with one cabochon-cut opal from Australia (11.99 ct), 349 blue sapphire beads (227 ct), six pear-cut emeralds (2.58 ct), and 394 brilliant-cut diamonds (7.40 ct).

Though we cannot see it on the photo (below), when the 22 x 27 mm Australian opal attached to the white gold segment is opened, it reveals a white mother-of-pearl watch dial powered by Piaget’s 56P quartz movement.

Piaget Sunny Side of Life Diamond Flow secret watch

To match, there is a unique piece 18-carat white gold Piaget Sunny Side of Life Diamond Flow secret watch (Reference G0A41265) with white mother-of-pearl dial, which is also set with one cabochon-cut opal from Australia (11.82 ct), two pear-cut emeralds (0.74 ct), 368 brilliant-cut diamonds (13.50 ct). The 22 x 27 mm Australian opal and white gold case also houses the Piaget 56P quartz movement.

Piaget Altiplano: 60th anniversary

The Altiplano case is one that has over the past six decades continuously broken world records for thinness. Turning 60 years old in 2017 was reason enough for Piaget to celebrate with a number of limited editions, including a few hard stone dial options in a svelte 34 mm case.

Piaget Altiplano 34mm Hard Stone Dial Opal

The milky, opalescent opal dial of one of the versions really caught our collective eyes with its shimmering white tones.

For more information, please visit piaget.com.

Quick Facts Piaget Altiplano 34mm Hard Stone Dial Opal

Case: 34 mm, pink gold set with 72 brilliant-cut diamonds (approx. 0.52 ct)

Dial: natural white opal from Australia

Movement: manually wound Piaget Caliber 430P, 2.1 mm in height, 43-hour power reserve

Functions: hours, minutes

Limitation: 38 pieces, boutique edition

Price: $48,000

* This article was first published on July 20, 2017 at Shrouded In Mystery And Fire: Opals In Jaquet Droz And Piaget Timepieces.

You might also enjoy:

Can Men Wear Women’s Watches? And If So: What, Where, And When?

5 New Ladies Timepieces Both Technically Intriguing And Aesthetically Captivating

Giberg Niura Flying Tourbillon: Elegant Style And Serious Substance

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

I am Speechless at the Opals , Opal Jewelry and Opal watches displayed here .

Ray Hemi “”Jewelray””

Opals are just beautiful stones…hard to make an ugly piece of jewelry with them!

I would like to ask you where exactly do I find the opal in wello region could you help me I am doing my research on wello opals and by the way I am a big fan of youe site ……

Thanks for reading! We specialize in mechanical watches, our interest in opals was really restricted to what you have read here. So I’m afraid we don’t have any further information for you. Good luck!

I can appreciate the author’s approach to explaining how Opal gained the negative reputation that it did back in the 19th century. I would not rule it out as a contributing factor. However there is another important point that I didn’t see mentioned. As explained in the book written by Paul B. Downing “Opal Identification & Value” which I found listed on the GIA website as, I believe, one of the more important and influential books written on Opal. The Author gave insight on what his findings were regarding how the “bad luck opal” myth was creatively marketed. His explanation was, and I am paraphrasing, that the myth was at least perpetuated by the Diamond industry as a way to sulli the reputation of opals as a result of the threat opals posed during surge in popularity which was causing a negative impact to the market value of Diamonds. If memory serves, Dr. Downing mentioned that the debate over the roots of the myth is, at the time of the release of the revised addition of his book, was still going on. But the version explained in this article is certainly interesting even without corroborating evidence. I enjoyed reading this article very much. Well done. I have a love affair with Opals and they are by far my favorite precious stone. Additionally, there is the fact that opals are more rare than Diamonds and can fetch as much or more per karat, for black Opal and even dark opals, than their Diamond counterparts on the world market. Thank you for the excellent read.

Thank you for your comments! My son (who now has a masters degree in journalism and communication) and I co-authored this article, and the idea for it came about during a car ride in which we were discussing my grandmother’s birthstone, the opal. I personally had always avoided buying and wearing opals because she was insistent that wearing them if it wasn’t your birthstone was bad luck. As I absolutely love semiprecious stones and gemstones that are not diamonds, we decided to get to the bottom of the bad luck legend. My grandmother was Scottish, so it was a great starting place for us.

We did not research at all how the diamond industry may have influenced this, nor did we use any official sources like the GIA in our hypotheses, so if you read anything like that into this article I assure you it is interpretation. My specialty subject is watches, not jewelry, so that would not have crossed my mind. But now that you’ve mentioned it, I can very much appreciate that that might have been so. Thank you!

Thank you so much for your input and well thought-out comment: this remains an ever-interesting subject to me!