When a hobby directs your professional life and results in a major invention, it probably means that your hobby IS your profession. This has likely happened more times than we know, but one of the most well known examples is the Super Soaker, a classic water toy invented by NASA engineer and part-time inventor Lonnie Johnson while working on a water-based cooling pump design.

Thanks to his engineering knowledge and experience with inventing, the Super Soaker became one of the most popular toys of the last 50 years. And all because he liked tinkering with ideas.

A lesser known example perhaps, but one that illustrates the power of hobbies to drive a professional career, is nineteenth-century French horologist Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, a man now famous as the father of modern magic.

Having studied clock and watchmaking, during his early studies he attempted to buy a two-volume set of clockmaking books entitled Treatise on Clockmaking by Ferdinand Berthoud, but instead received a two-volume set about magic called Scientific Amusements. Mechanical magic instantly captivated Robert-Houdin, and while he continued his career in clockmaking, magic became his passion.

While developing his skills and becoming interested in performing, he invented many marvels that stunned audiences over his long career. But he didn’t abandon clocks and automata; instead he doubled down on creating unique inventions including a singing bird and a mechanical figure that could write and draw.

And while he invented dozens (if not hundreds) of mechanical creations to aid in stage magic, his most lasting legacy in the world of horology is due to his experiments with glass, dabbling with techniques of implementing glass structures to create “invisible” actions or hidden mechanisms to wow audiences with magic performances.

One result of this dabbling was a clock that appeared to have no gears driving the hands, seeming to float in midair unattached to anything.

If what I am describing sounds familiar, that is because it was the first instance of a mystery clock, a design that would go on to become famous, utilized by talented clock and watchmakers throughout the last 150 years.

And Robert-Houdin’s mystery clocks were the inspiration for Cartier’s own examples more than 65 years later, as of 1912 with the help of master clockmaker Maurice Coüet.

Cartier presented a set of 19 mystery clocks from its famed collection at SIHH 2018 that showcased the incredible artistic range the brand has displayed over the decades as well as the skilled craftsmanship needed to assemble such creations.

And to think, it was all made possible because a young watchmaking apprentice was accidentally delivered with the wrong books.

Cartier: a modern king of mystery

Cartier’s career in mystery clocks began in 1912 with Model A, a largely standard-shaped mantel clock that appeared to be made entirely out of rock crystal with no indication that the invisible dial was in any way connected to a mechanical movement.

While boxy, the shapes of the rock crystal case and glass dial seemed like magic, with whatever was driving the delicate (and often jeweled) floating hands nowhere to be seen.

Model A Cartier Mystery Clock from 1912 featuring platinum, gold, white agate, rock crystal, sapphires, rose-cut diamonds, and enamel

The secret was found in two columns encased in the rock crystal on either side of the dial inside of which two axles extended from the movement hidden in the base to engage with the dial made of two separate glass disks mounted in thin metal ring gears hidden by the bezel of the hour track.

The hands, fixed to the glass dials, rotated relative to each other with no obvious connection. It really was a stunning creation, proving popular among collectors at the time.

Cartier workshop at 53 rue Lafayette, Paris, circa 1927 (photo courtesy Cartier archives)

In 1920, the mystery clock designs expanded to include pedestal or single-column shapes. These matched the design of Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin more closely, greatly exceeding the amazement caused by the Model A clocks.

Now a single, completely see-through crystal column supported the large clock dial, giving the impression that nothing could be driving it as the support was now effectively transparent. The Model A contained a section that wasn’t transparent, allowing a metal mechanism to be hidden, but with these new pedestal styles a new solution was needed.

The answer was a glass axle inside the pedestal column, making it very hard to notice. Since a single axle was now driving both dial disks, the connection could be made smaller thereby increasing the illusion.

With these new developments, custom examples were being created for the most discerning clients, including international royalty and Hollywood celebrities.

Kicking the mystery up another notch

Most of the mystery clocks made over the years were based on these two main designs, at least in functionality. Choosing the shapes and materials provided nearly infinite possibilities and resulted in some truly stunning examples.

Cartier mystery clock on elephant base owned by the Maharajah of Nawanagar

The Maharajah of Nawanagar owned a mystery clock that was one of a 14-part series featuring animals or figurines carved in stone as the base of the clock. The Maharajah’s clock was a gentle sleeping elephant carved in jade that hid the movement. It was number ten of the series and showcased the variety possible within Cartier’s studios.

But the six Portique clocks made between 1923 and 1925, representing the third main design variation, represented the pinnacle of the style. This clock featured a dial suspended from a surrounding frame as if by a metal chain, taking the illusion to the absolute maximum.

Behind the scenes, the “chain” was in fact not a chain and thick enough to hide the axle running down through its center, though the final touch was a rock crystal crossbar whereby the axle was only hidden by a very small coral cabochon. It seemed impossible for the movement to be driven through this area, making this design a triumph of the era.

It also turned the genre on its head since the movement was no longer hidden in the base like the other designs.

Portique: forming the Cartier Collection

An example from 1923 is actually what prompted the formation of the Cartier Collection when the Parisian brand purchased it at auction in 1973, 50 years after its creation.

Cartier Portique Mystery Clock

The Large Portique Mystery Clock was originally acquired by Polish opera singer Ganna Walska, who not only was an extraordinary gardener (she created the Lotusland botanical gardens at her mansion in Montecito, California) but was also a socialite and all-around diva. She married six times, and one may assume she held many swanky parties during the Roaring Twenties – with the Cartier Portique Mystery Clock watching the festivities and wowing the guests.

It was enthusiasts like this who helped Cartier in many ways, as Walska was a connoisseur of Cartier jewelry as well. The story of this clock inspired the brand to begin seriously collecting important pieces from its past, debuting the Cartier Collection in 1983.

Today, that collection contains more than 1,600 pieces of jewelry, watches, clocks, and other precious objects from the brand, including 20 different mystery clocks.

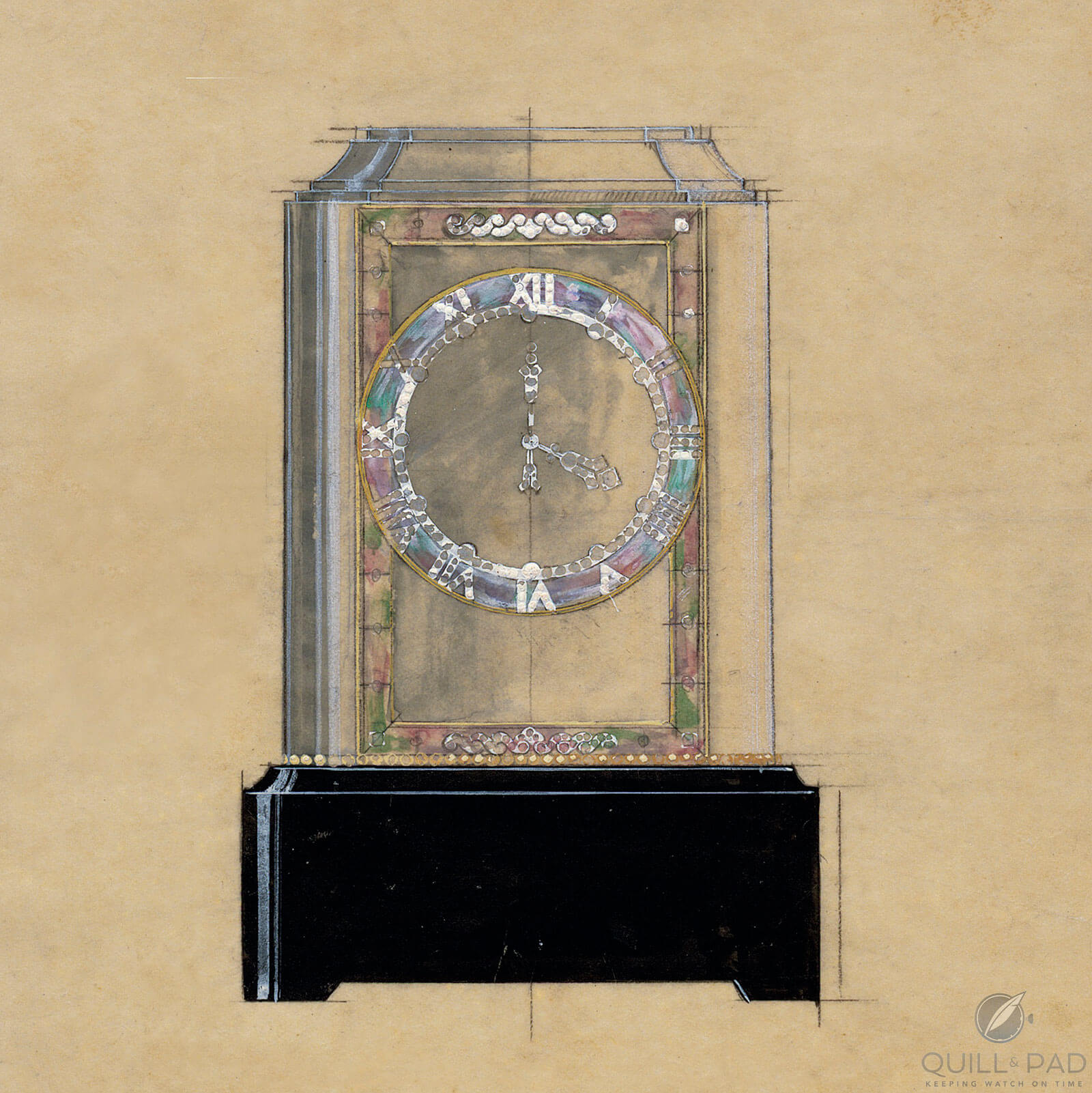

Sketch of a Cartier Mystery Clock from 1929

Displaying Cartier mystery clocks

The exhibition at SIHH 2018 included 19 of the 20 clocks, and it was a rare sight to behold so many examples from across the decades. The oldest piece in the collection is a Model A from 1914, while the youngest is a pedestal example from 1967.

That might make you wonder when Cartier stopped producing these clocks. The answer is that the brand never has; it has been more or less continually producing them since the introduction in 1912.

Of course, it must be said that a majority can be attributed to clockmaker Maurice Coüet, who was responsible for many of the pieces during the height of the production, which lasted pretty much until the Great Depression.

During those two decades, many clocks were made, though no official record of every piece has survived, so no grand total can be known or even accurately guessed at according to Cartier. But the mystery clock has been present since before World War I with new versions appearing every so often.

With the advent of electric clocks and new technologies, mystery clocks (and later watches) began to be offered by others. But as brands go, Cartier and mystery clocks are nearly synonymous with each other; Cartier clearly has crafted some of the most stunning examples the world may ever see.

Model A has probably been the most popular over the past century, but there have also been quite unique pieces crafted along the way – such as a “plate” clock that was conceived to rest horizontally on a table and be viewed from above. The movement is hidden in the number six, clearly a more modern interpretation of a fairly old idea.

Cartier Mystery Clock

As a horology nut and mechanism nerd, the mystery clocks and watches have always fascinated me and having the opportunity to see so many varieties up close and to discuss the pieces, history, and entire Cartier Collection with Cartier was an awesome experience. My favorite part was trying to see what I wasn’t supposed to be able to see: the geared disks and drive axles.

But what most probably is my takeaway from the exhibition and the mystery clocks is just how incredibly creative Cartier can be. The variety and skill on display would be tough to beat regardless of collection or provenance. The mystery clocks represent not only an important part of Cartier history but also an interesting side branch of horology exploration that is still being dabbled with even today.

I’m disappointed, though, that there has been no visual demonstration as to how the movements work, which I would imagine might be extremely interesting even to the casual observer. But since I will always want to see how the sausage is made, I can’t really hold that against the organizers of the exhibition.

And, at the end of the day, the clocks retain their categorical titles as mystery clocks even though now we are all the wiser. I imagine that Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin would be happy knowing that his horological babies were adopted so wholeheartedly and creatively.

For more information, please visit www.cartier.com/en-us/pages/events/mystery-clocks-cartier-collection.

You may also enjoy:

Cartier Rotonde de Cartier Astromystérieux: An Illusion Inherited From The Father Of Modern Magic

Cartier Minute Repeater Mysterious Double Tourbillon Is The Cat’s, Er, Panther’s Meow

The Rise And Fall Of Fine Watchmaking At Cartier: It’s Been Surprisingly Complicated

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] Cartier’s Mystery Clocks An article on Quill & Pad […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Nice article. I was just admiring the picture of the Cartier Rotonde Astromysterieux on p83 of Ryan’s Wistwatch Handbook.

On a more affordable level, the Konstantin Chaykin Levitas has the same feature.

Where does the information about 19 hours come from?

I found only 11.