The 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award has concluded: the dust has settled, the tools have been put down, and the participants are on to other tasks.

The winner of the 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence award, Otto Peltola, was announced at SIHH 2019 at the annual Lange Friends Dinner, which included journalists, collectors, and, as the name implies, friends of the brand.

Otto Peltola’s Ostinato took first prize in the 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award by A. Lange & Söhne

It may seem like a long time has passed since I first reported on the beginning of the competition back in May 2018 in Behind The Scenes Of The 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award, Now Underway, but in the interceding months time truly flew by for the contestants as they brainstormed, sketched, cut, turned, filed, polished, assembled, tested, adjusted, and reassembled their projects in an attempt to be crowned this year’s winner.

Contestants in the 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award being briefed by Anthony de Haas (center), with winner Otto Peltola at his direct right (photo Erik Gross/A. Lange & Söhne)

Eight worthy contestants put their blood, sweat, and tears into some fantastic ideas for an interesting and innovative acoustic indication, then worked diligently over nearly seven months to realize the designs mandated to include a chiming element.

In my first report, I posited a variety of possibilities that I thought the contestants might follow, and some did follow paths I had imagined. But others were stunningly outside the box. This goes to show that creativity isn’t dead in watchmaking school, and the future holds big surprises for all watch enthusiasts.

You may want to look at Behind The Scenes Of The 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award, Now Underway for a refresher of the project and its participants.

It may come as no surprise that the winning project came from the competitor with a deep background in music and featured a musical cord progression when you know that the task should include a chiming element. The top prize went to Otto Peltola from the Finnish School of Watchmaking for his watch Ostinato, which features a musical quarter chime in passing striking a chord of three notes every 15 minutes across a staggering array of six gongs.

The result wowed the judges and edged out some tough competition from some very talented students.

While it is easy to look at the finished projects and judge them from a distance, I prefer knowing the process of creation to learn understand how to better one’s skills. That is why I kept in touch with the competitors over the course of the project: to get a little peek into each student’s process and perhaps glean some nuggets of triumph and failure from the group.

Today I offer a glimpse into what it was like for the students to participate in the Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award and highlight some details that show how passionate and clever these students are. I’ll also go into more detail on Peltola’s winning submission as well as that of the two runners-up, Linda Holzwarth and Yutaro Iizuka, who provided exceptional entries that also stood out to the judges.

Long road of development

The process began the day after all the competitors returned home from the week in Glashütte, and by the time I had checked in with them for my first article just a couple weeks later every one of them had plenty of ideas. But ideas don’t just translate into workable designs, and often the students had to do more research to confirm these were valid.

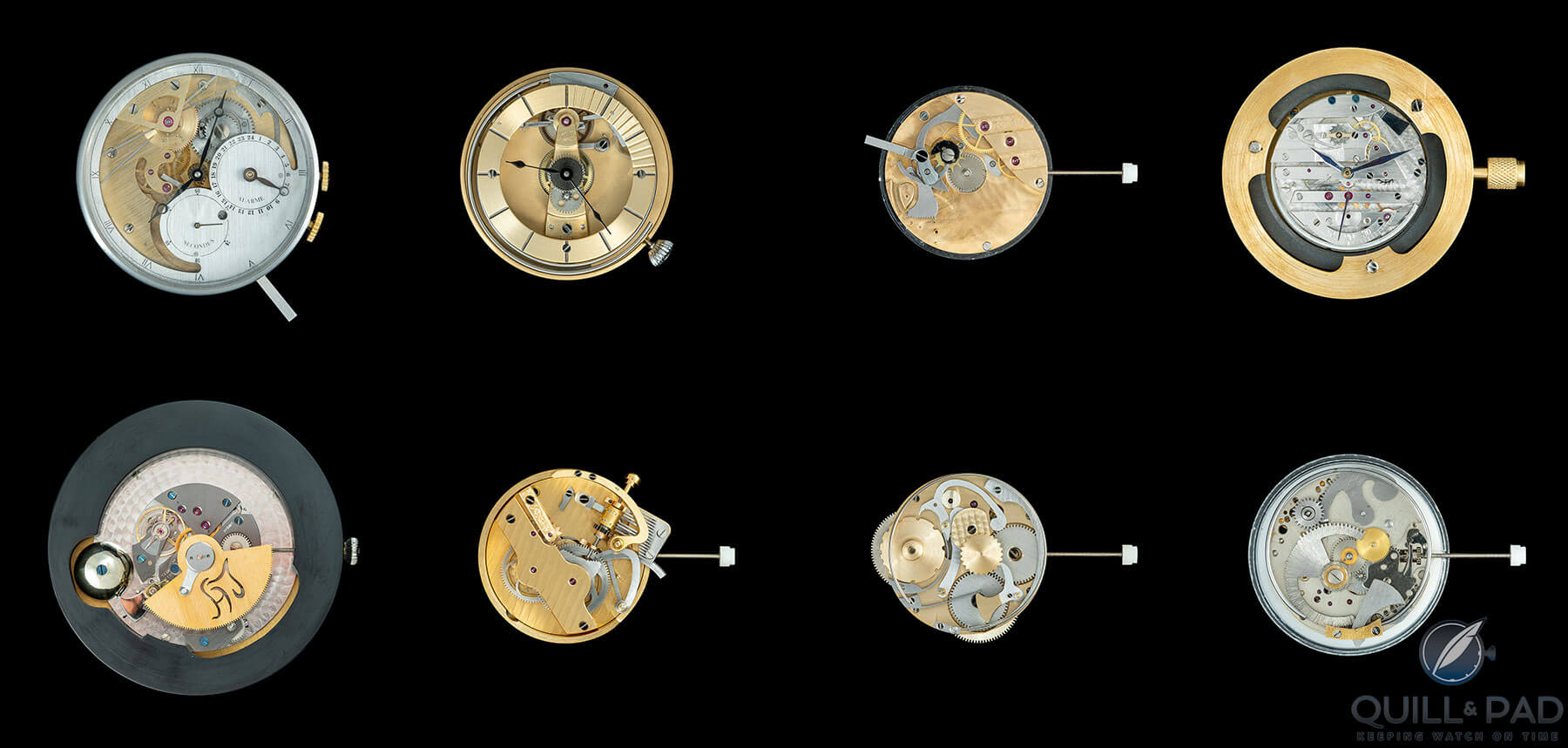

The eight projects entered into the 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award

Take Holzwarth as an example. Hailing from the Goldschmiedeschule mit Uhrmacherschule in Pforzheim, Germany, she had an idea to create an acoustic power reserve indication since the provided ETA 6498 base movement is a manual wind without a power reserve function. During the initial brainstorming, she concluded that the function should be based on an up-and-down mechanism. And thanks to some texts by Alfred Helwig and Horst Hassler, two solutions in particular were put forth, one of which seemed daunting while another seemed like a safe bet.

Linda Holzwarth from Pforzheim received a commendation for her project entered in the 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Awards

But after further sketching, design, and building a physical model to test the leading idea, it was determined that the first choice, a friction clutch/ratchet wheel configuration, was a dead end and the more difficult mechanism based on a differential was the best workable solution. Which meant that Holzwarth now needed to manufacture her very own micro-differential, no trivial task in itself.

This led Holzwarth to manufacture another prototype to determine if the mechanism was feasible with her equipment and skills as the entire design now hinged on a custom differential. The idea proved successful and then the real development began.

Yutaro Iizuka had a similar story for a much different idea. Iizuka, who studies at the Hiko Mizuno College of Jewelry & Watchmaking in Tokyo, wanted to construct an indication that is rather rare: one that chimes at a specific temperature. Clearly, he would have his work cut out for him. Using Abraham-Louis Breguet’s invention as inspiration, Iizuka researched how to successfully create a bimetal thermometer, discovering that when Breguet crafted one he used a combination of zinc and steel. Iizuka did as well.

Yutaro Iizuka from Tokyo’s project received a special commendation in the 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Awards

It took more than a month and numerous tries to create a bimetal element that would function properly, which then prompted research into how to tune and calibrate the element. All of this needed to be accomplished before the mechanism could truly be designed as the physical properties of the element he made would determine where and how the component could interface with the rest of the thermometer mechanism.

This same story was loosely shared across many of the students’ projects. Peltola, the eventual winner, spent a long time focusing on creating his six gongs and tuning them before continuing with the rest of the design as his entire concept was based on the accurate creation of multiple musical chords.

Both Aaron Rüegger and Per Pucher, students at ZeitZentrum Uhrmacherschule in Grenchen, Switzerland, stated that the design for their projects was in flux well into construction as the exact configuration wasn’t finalized until some critical components were successfully created. And pretty much all the students had to work around their actual student work, exams, and the limited availability of workshop time during the summer when school wasn’t in session.

Making sounds, beautiful and varied

By the time I got back in touch with everyone with a little over two months left until the deadline, all the students were well on their way to creating the awesome projects they would submit. Of course, I did hear about designs still not being completely finalized for the reasons I mentioned before, and many had already had their fair share of failures and setbacks that proved just how hard the task was.

It was also clear that many of the students were learning by leaps and bounds just to complete their projects, and based on what was submitted I think it was because the competitors were pushing themselves a bit further than they believed they could do. A lot of swinging for the fences in this bunch.

But regardless of the design direction, the final result still needed to include an acoustic indication, which meant everyone needed to make something that created a sound in some way. It turns out the group was more than up to the task – and then some.

Two competitors, Matéo Cattin of Lycée Polyvalent Edgar Faure in Morteau, France, and Rüegger, both went down the path of creating music box-style acoustics. Cattin created an alarm that used a mechanism reminiscent of the Ulysse Nardin Stranger that plucked tuned comb fingers, while Rüegger developed a sliding cylinder that used two rows of pins activating a tuned comb in different pairs of tones based on interfacing with a stepped wheel.

Holzwarth took a different approach, using a nickel-silver bell to indicate the power reserve, mounted just off the side of the main movement. This almost surely provided a very significant sound given the size of the bell.

Iizuka’s work was a real standout. Understanding that achieving a beautiful tone with metal was exceedingly difficult, he turned his attention to musical instruments for inspiration and landed on the lithophone, a sibling instrument to the xylophone or marimba. The lithopone uses special stones that are of the right composition to create lovely tones when struck.

In Japan, the Sanukite stone is commonly used for this purpose, often being made into wind chimes as well, meaning the stone is relatively easy to obtain. Iizuka tested with the stone and found it to provide a very rich sound most could only hope for. And since it is a natural material, each piece of stone is unique, sounding slightly different than the others, meaning that only Iizuka’s watch will have those exact tones.

The other half of the field created more traditional gongs, no easy task in itself as making a gong generating a clean and clear tone is extremely difficult. As Peltola’s winning example shows, tradition is tradition for a reason. And when you multiply tradition six times you are bound to make someone sit up and take notice.

Regardless of the techniques used to create the sound, all of the pieces showed creativity in the implementation, and no two pieces used similar mechanisms or methods. It was fantastic to see varied approaches to the same problem.

Ostinato by Otto Peltola: the winner

As previously stated, Peltola, the winner of the competition, was from the Finnish School of Watchmaking in Leppävaara, Espoo, Finland. With his musical background and knowledge of acoustics and musical theory, Peltola set about to create something that had harmony and was as rich as possible for such a small mechanism.

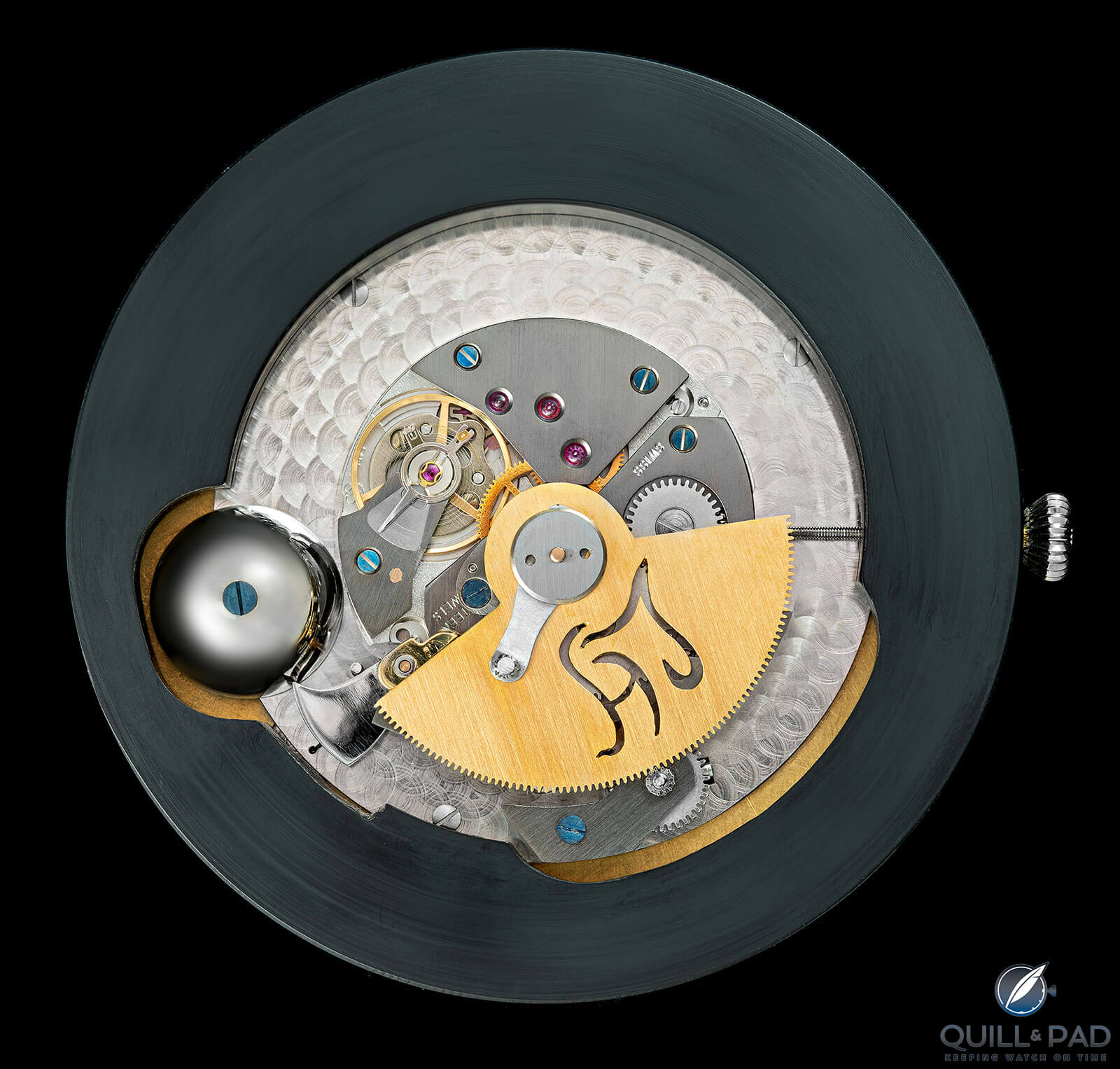

Otto Peltola’s Ostinato

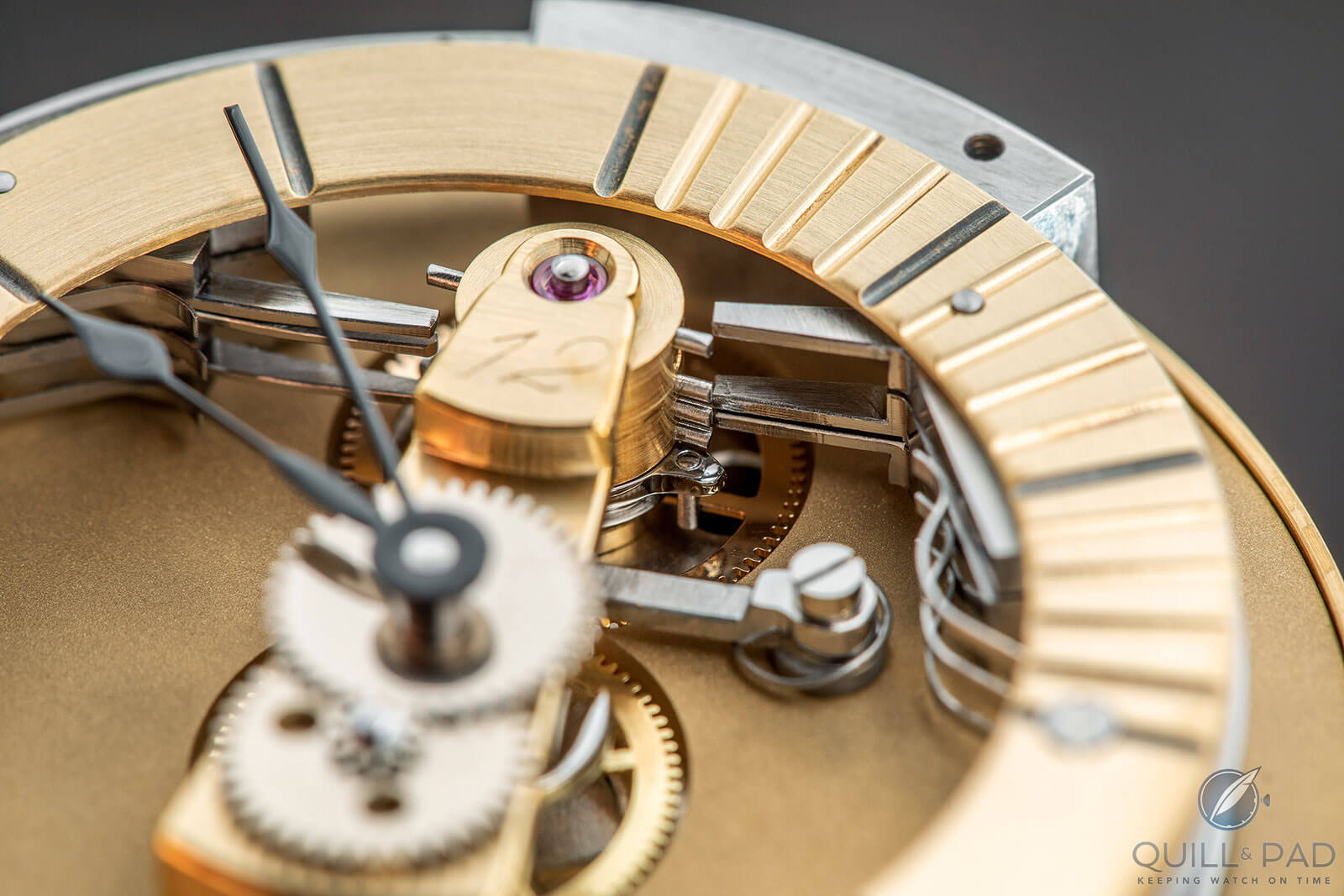

He realized that focusing on chords could help him achieve his goal of a meaningful sound on such delicate gongs. Using a chord progression of triads (three notes) he created a quarter chime in passing that cycles through chords in the key of C major.

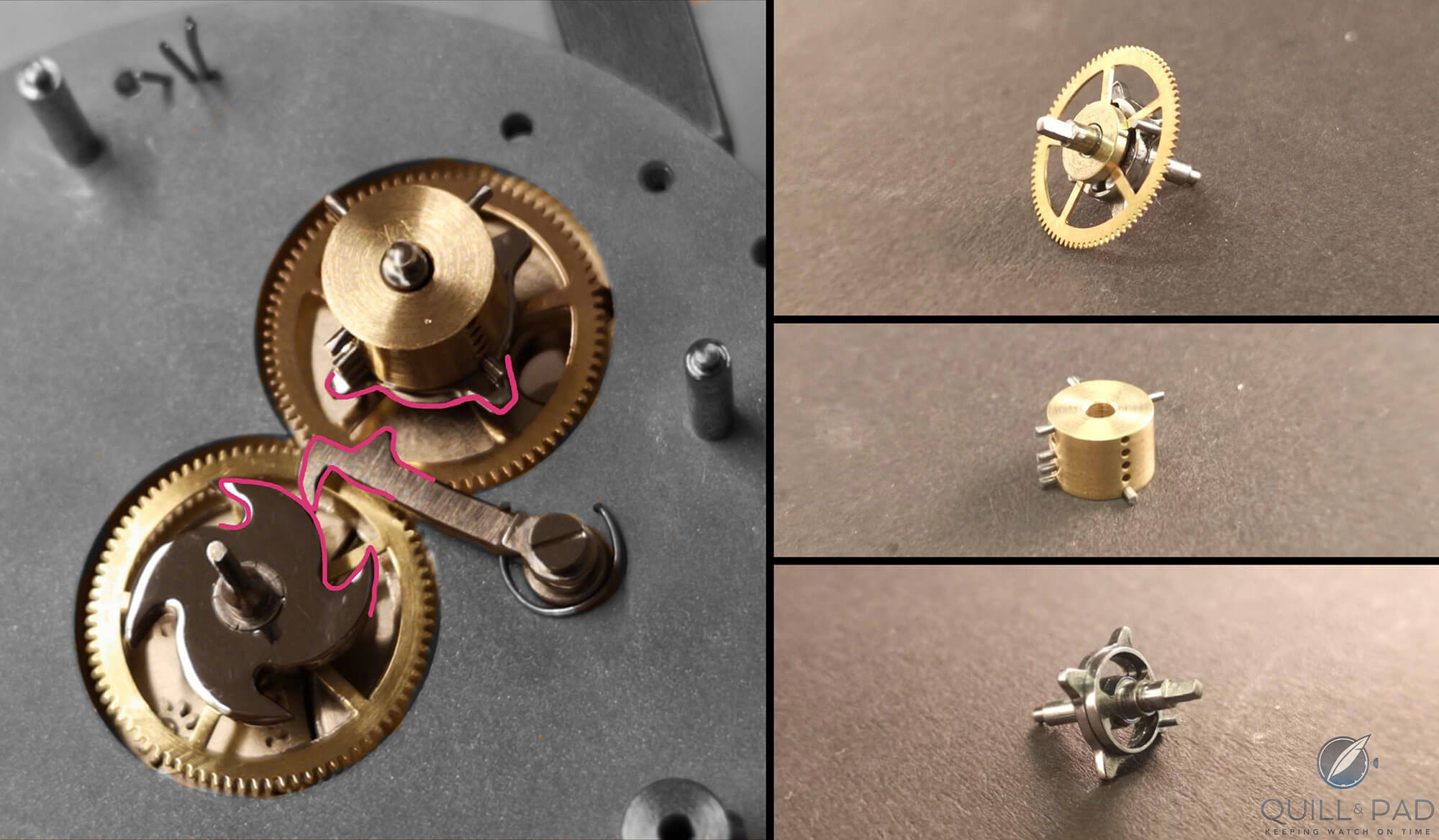

It specifically cycles through the C major, A minor, F major, and G7 major chords every 15 minutes using six gongs and six hammers. The hammers are driven by a vertical cylinder with four vertical rows of five pins, or at least five positions for the pins. Depending on the chord played, the pins might activate gongs on one or both sides, and the hammers have specific offsets to engage in the proper order based on how the pins are installed.

The pin cylinder is mounted to a four-pointed star and a gear wheel, but is not locked to the rotation of the wheel. The cylinder and star wheel connect to the axis of the gear wheel with an intermediate spring that allows for approximately 72 degrees of rotation. The reason for this is as follows: when the gear wheel rotates, the pin cylinder rotates with it until it is stopped by a locking arm at one of the four-star wheel positions. This locking arm is riding on a four-arm snail cam attached to the primary driving wheel. The two gear wheels continue to rotate as time passes, but the cylinder is locked and being charged for the jump with the intermediate spring.

The mechanism in Otto Peltola’s Ostinato responsible for controlling the chimes

When the locking arm falls off the snail cam arm, it unlocks the pin cylinder allowing it to jump forward to catch up to the gear wheel it is mounted on. This jump allows an instantaneous release of the pin cylinder and the hammers for a coordinated chord chime. This ballet of mechanics happens every 15 minutes, meaning the chord progression is never too far away to share with your friends.

The movement features a very minimal dial and a simple ring around the edge that hides the hammers from view. This is quite purposeful as the dial ring actually acts as a bridge for the hammers, making the part a critical component to the function of the chime in passing. A central cock supporting the rest of the components runs vertically up the center of the dial, supported at only one end, and has the number “12” engraved to help orient the dial visually.

The finishing is simple yet clean, and the six gongs are nicely polished.

The result is stunning, and Peltola admitted he surprised himself as he struggled to begin the project among his other work and the summer holiday. He didn’t truly get working in earnest until August (the deadline was the first week in November), which put him at a disadvantage over those who were able to work through the holidays. Still, he put his nose to the grindstone and earned admiration from the judges and A. Lange & Söhne for his efforts.

The Ostinato chiming watch by Otto Peltola, winner of the 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award

Peltola felt his biggest hurdle in the project was creating the gongs and the chord mechanism. He was so invested in the musicality of the watch that he knew he needed to make something that sounded fantastic. Once he was finally happy with the sound, he felt a huge weight removed from his shoulders. The sound was also what he felt was his greatest achievement since music is so important to him personally.

How the competition played out

But no matter how satisfied someone is with a project, it still has to be judged. And that is exactly what took place in November as the four jury members gathered at A. Lange & Söhne’s headquarters in Glashütte.

In addition to A. Lange & Söhne’s director of product development Anthony de Haas, the jury consisted of German watch journalists Gisbert Brunner and Peter Braun as well as the director of the Royal Cabinet of Mathematics and Physics Instruments in Dresden, Peter Plassmeyer. Each jury member brought a unique perspective as they dissected and discussed each piece.

Winner of the 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award Otto Peltola receiving his project instruction booklet from A. Lange & Söhne’s Anthony de Haas

But what exactly helped the Ostinato take the top spot?

According to head judge de Haas, the jury instinctively looks for very specific things right off the bat. He states that, “When you hold the movements in your hand for the first time, you immediately ask yourself, are they clean? Have they been finished? What do the surfaces look like? How creative and original is the whole thing?”

The jury also looks for things like functionality, craftsmanship, originality, and aesthetics, signs that skill and purpose were driving the creation of the submissions. De Haas went on to say that, “This year, Otto’s project was the one that inspired us the most. He quickly emerged as the winner. He had an extraordinary idea and put it into practice perfectly with an homage to the acoustic display. To make six gongs, you have to first do it and then deal with it. I think that is completely underestimated.”

But the jury could not ignore the other submissions, all of which showed talent, passion, and skill dedicated to creating something new.

“The craftsmanship is often the most surprising thing. This is proven by projects like Linda (Holzwarth)’s, who linearly and logically implemented an idea – from the preliminary consideration to execution and project documentation,” de Haas continued.

I asked him specifically if anything was utterly unexpected or surprising this year and he said, “It was the movement submitted by our Japanese participant, Yutaro Iizuka. He chose an outer ring made of Japanese rock – Sanukite – and acoustically solved a temperature difference display. He used the stone as a sounding body and modified the basic movement considerably. I did not expect that, and that definitely positively surprised me.”

De Haas also explained, “We are often surprised by the modesty of the solutions. The completely different approaches of the group are also exciting. There are those who concentrate on classic solutions and there are others who go completely new ways. Both can be great.”

As often happens in a competition on a deadline, people can get too focused on the details. And de Haas reiterated that this always leads to some missing the mark due to less-than-functional projects.

A close look at the gongs of Otto Peltola’s Ostinato

“We often see watches that do not achieve their goal. That is why we try to warn against it. The students spend a week with us in the spring and are super ambitious afterwards. That is exactly the danger – they get lost in details and are unable to finish the piece in the end. They underestimate the implementation process. Six months is a very short period of time when you consider that the watchmaker training course runs at the same time. That is why we say to them, ‘start right away and don’t get bogged down in details’.”

It is clear that the jury must have had a tough time judging all the pieces this year as de Haas explained, “When we sit together with the jury in November, the first impression is always the same: ‘Hey! Wow! That’s good! This work is super exciting’!”

Taking eight submissions from very talented students requires some tough love, if you will, as one always stand out as the best implementation, but this does not negate the quality and hard work of all the other competitors.

Judging by the group photo of the submitted movements, it definitely looked like a good crop for the jury to focus on. And luckily for Peltola and his Ostinato, the jury unanimously agreed that his piece get the highly coveted nod.

A word from winner Otto Peltola

When asked what he learned most from this competition, Peltola had a surprising (or perhaps not that surprising) answer. A bit before the competition entry deadline, in late winter of 2018, Peltola admitted he was wrestling with the idea of even taking part in the competition as it seemed rather daunting.

He was worried he might fail, which to me sounds like a very understandable concern when attempting something so large for the first time. After speaking with his family and friends, and most specifically his girlfriend, he was convinced to make the attempt and applied for the competition.

His girlfriend provided much-needed encouragement through the entire process, helping Peltola stay motivated during the inevitable hard times of creating something new. She more than once said, “Look what you’ve made; you have come a long way. You almost didn’t even apply.” To Peltola, the most lasting impression he was left with was that you have to believe in yourself.

And I think this competition is a perfect example of that lesson. Eight young watchmaking students came together with dramatically different backgrounds and motivations to take part in a competition that required maturity and a pursuit of excellence. But more importantly, they simply learned to believe in themselves.

They all worked hard and persevered, creating something that they could be proud of. Even those facing very significant challenges, or not succeeding in creating what they had in their heads, still made something very difficult.

The 2018 edition of the Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award was a long road that went by too fast it seems to me; we are already gearing up for the 2019 edition as schools around the world put forth their best watchmakers.

I loved being a part of this story and getting to see the inner workings of the greatest student watchmaking competition in the world. The people involved from A. Lange & Söhne as well as the students proved that passion and dedication can create opportunities from dreams.

I want to congratulate every competitor for a job well done; it was an honor to cover your journey. I also want to thank the fantastic people at A. Lange & Söhne for their kindness and generosity in giving me the rare opportunity to be a part of the process. I am looking forward to hearing about the next competition, and I wish all potential competitors good luck.

And remember to believe in yourselves!

For more information, please visit A. Lange & Söhne’s Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award page.

You may also enjoy:

Behind The Scenes Of The 2018 Walter Lange Watchmaking Excellence Award, Now Underway

The Life And Times Of A. Lange & Söhne Re-Founder Walter Lange

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!