Visiting Seiko’s Haute Horlogerie Micro Artist Division

Seiko’s story is much more complicated than most people might think. This is a manufacturer that not only followed a trend, but actually created some of its own, capitalizing on expertise, knowledge, and skills that were practically the mother of necessity for this manufacturer located so far away from the established European centers of watchmaking.

Grand Seiko Spring Drive 8-Day Power Reserve Caliber 9R01 (Ref. SBGD202)

Contrary to popular belief, Seiko’s history did not begin with the quartz watch in the 1970s, nor has it ended there. This Far Eastern giant has banked on innovation for the last 138 years and now masters more types of watchmaking than any other company making timepieces today.

Seiko is in my opinion the most diverse watch manufacturer on the planet – particularly since 2000 when its own style of haute horlogerie was called to life. But before we explore that more, I’d like to review a few salient historical points of this veritable giant of watchmaking.

Seiko Morioka factory

A little Seiko history

Seiko’s long history began with Kintaro Hattori’s watch store established in 1881 on the Ginza, Tokyo’s swanky shopping avenue. That shop still exists today, embedded in luxury department store Wako, a division of the Seiko Holdings Corporation, and continues to carry some of the world’s most luxurious Swiss watch brands.

Wako department store on Tokyo’s Ginza

There was no watch industry in Japan at the time of Hattori’s establishment; all the watches offered for sale were bought in Switzerland, Germany, and even the United States, which had a lively pocket watch industry during that period.

In 1892, the Hattori family founded a factory to make clocks and called it Seikosha, which can be translated as “precision factory.” A short three years later, in 1895, the company began making pocket watches.

In 1913, Seiko added mechanical wristwatches to its repertoire in accord with the trend of wearing portable mechanical timekeeping at the time. From here on out, Seiko, which now comprises three corporations (Seiko Instruments, Seiko Holdings, and Seiko Epson), can boast more than a century of mechanical history on the wrist.

Seiko is perhaps best known for making the quartz watch affordable and wearable from 1969 – incidentally the same year the company came out with an integrated automatic chronograph with column wheel and vertical clutch, released at just about the same time as Heuer and Breitling’s joint-venture Caliber 11 and Zenith’s El Primero. However it should not be overlooked that the company continued to make mechanical watches throughout this period and beyond, even learning how to manufacture every component in-house as suppliers were in short order.

As recently as a decade ago, mechanical watches by Seiko were generally available only in Asia. Since 2010 the Grand Seiko sub-brand has been available worldwide and has been steadily gaining in reputation and popularity.

Additionally, Seiko continued to add other groundbreaking technology to its roster since the advent of the quartz watch, including the Kinetic from 1988, an autoquartz technology that converts the power of the wrist’s movement into electricity. Ten years ago, the Kinetic, whose collection encompasses no less than 23 calibers, made up the lion’s share of Seiko’s international sales.

But perhaps more important has been the Spring Drive movement.

Seiko Spring Drive

The late 1990s set the scene for the Spring Drive, a technology patented in 1978. Its inventor, a young Seiko Epson engineer by the name of Yoshikazu Akahane, got the idea for it from a bicycle coasting on a slope at constant speed.

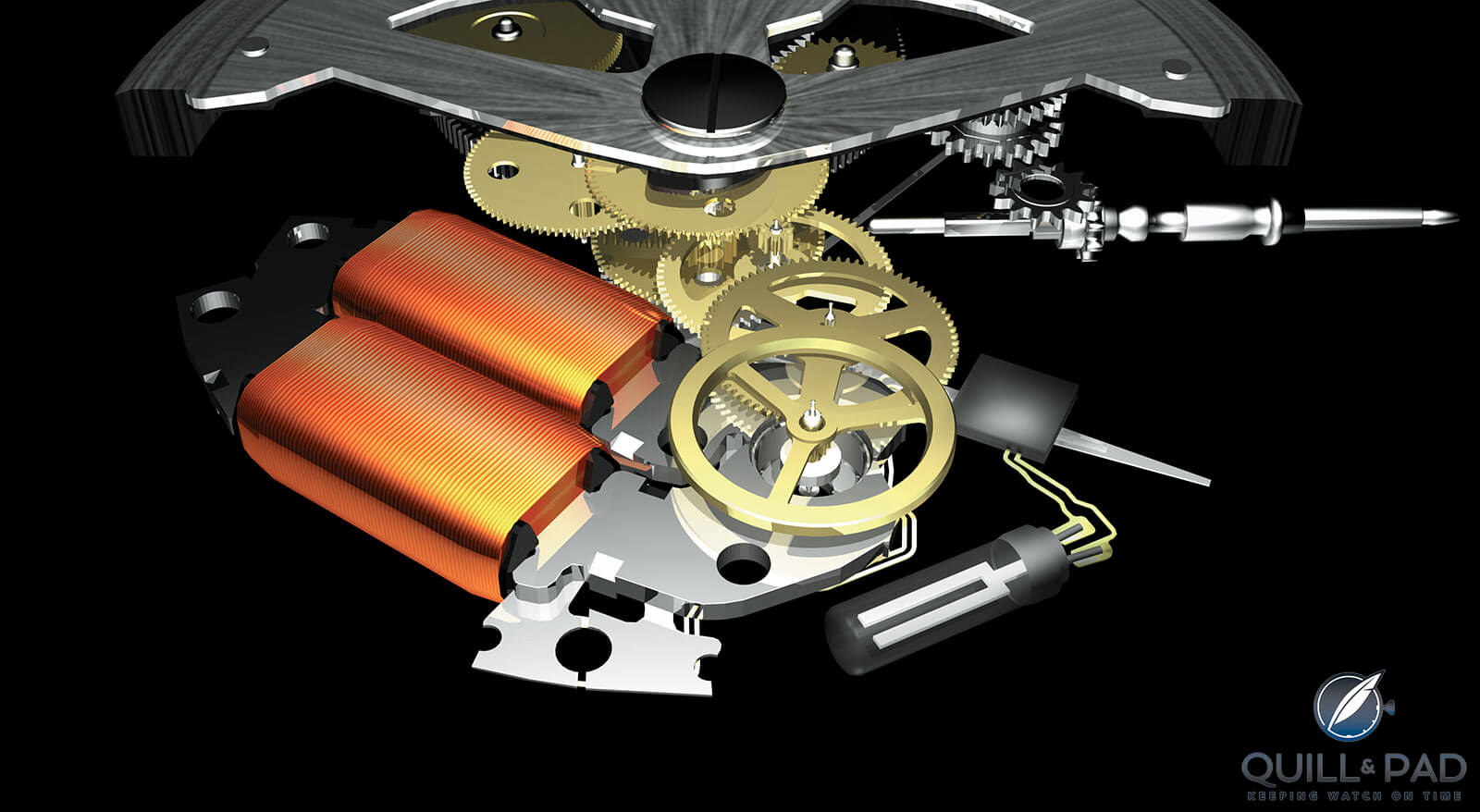

Exploded view of Seiko’s Spring Drive movement

Though the first prototype was introduced in 1982, Seiko dedicated 20 years to research and development before being satisfied that the Spring Drive technology was ready for serial production.

The realization of the Spring Drive once again hinged on Seiko’s uncanny ability to fuse the old with the new. This movement combines a mechanical hand-wound or automatic movement with an ultra-modern generator for mechanical, electrical, and electromagnetic energy that does not emit a ticking sound, justifying and explaining the company’s tagline, “the quiet revolution.”

The Tri-Syncro Regulator is an important and unusual element of the Spring Drive movement

The goal was to make a precise watch – astoundingly precise, within one second deviation per day – requiring no battery replacement.

With its large body of skilled and talented technicians and watchmakers, Seiko naturally doesn’t rest on its laurels. The next step, however, may have come as a surprise to many for it represented as much of a step back into the annals of watchmaking history as a jump forward.

Haute horlogerie from Seiko’s Micro Artist Studio

Though the idea of the collective is generally the norm in Japan, and Seiko doesn’t necessarily like to put the spotlight on individuals, credit must be given where it is due. And so Kenji Shiohara, like Akahane before him, is justifiably credited for kicking off something new that merged the traditional with the modern, seemingly a specialty of Seiko.

Entering the Micro Artist division of Seiko’s Shiojiri factory

Since the beginning of Seiko’s quartz era, this company had mainly pursued efficiency and automated production. Skilled craftsmen, though still to be found within Seiko Epson, were no longer a necessity.

Shiohara was part of the last group of Seiko technicians to acquire mechanical watchmaking skills to become a First Class Skilled Watch Artisan, a Japanese national qualification that corresponds to the established title of master watchmaker and includes skills needed to properly regulate a mechanical watch and make complications. Seiko is especially proud that he also won a gold medal in the now-defunct International Skill Olympic competition.

Seiko watchmaker Kenji Shiohara won the gold medal at the International Skill Olympic Games in 1979

In 1999, something extraordinary happened. The company’s president at the time owned a filigreed mechanical watch made and sold under the aegis of the Swiss Jean Lassale brand, which had been owned by Seiko since 1979.

This hand-wound specialty, a mere 1.2 mm in height, was in need of repair, and Shiohara was called to perform. At the time, he was probably the only one at Seiko able to successfully restore the piece to its former glory.

Shiohara discovered not only a new side to his own creativity through the repair of this complicated timepiece, but also began to think hard about how to increase the longevity of a watch. These thoughts led him to voice his opinion to his superiors, something not necessarily done within the hierarchical system of the Japanese culture.

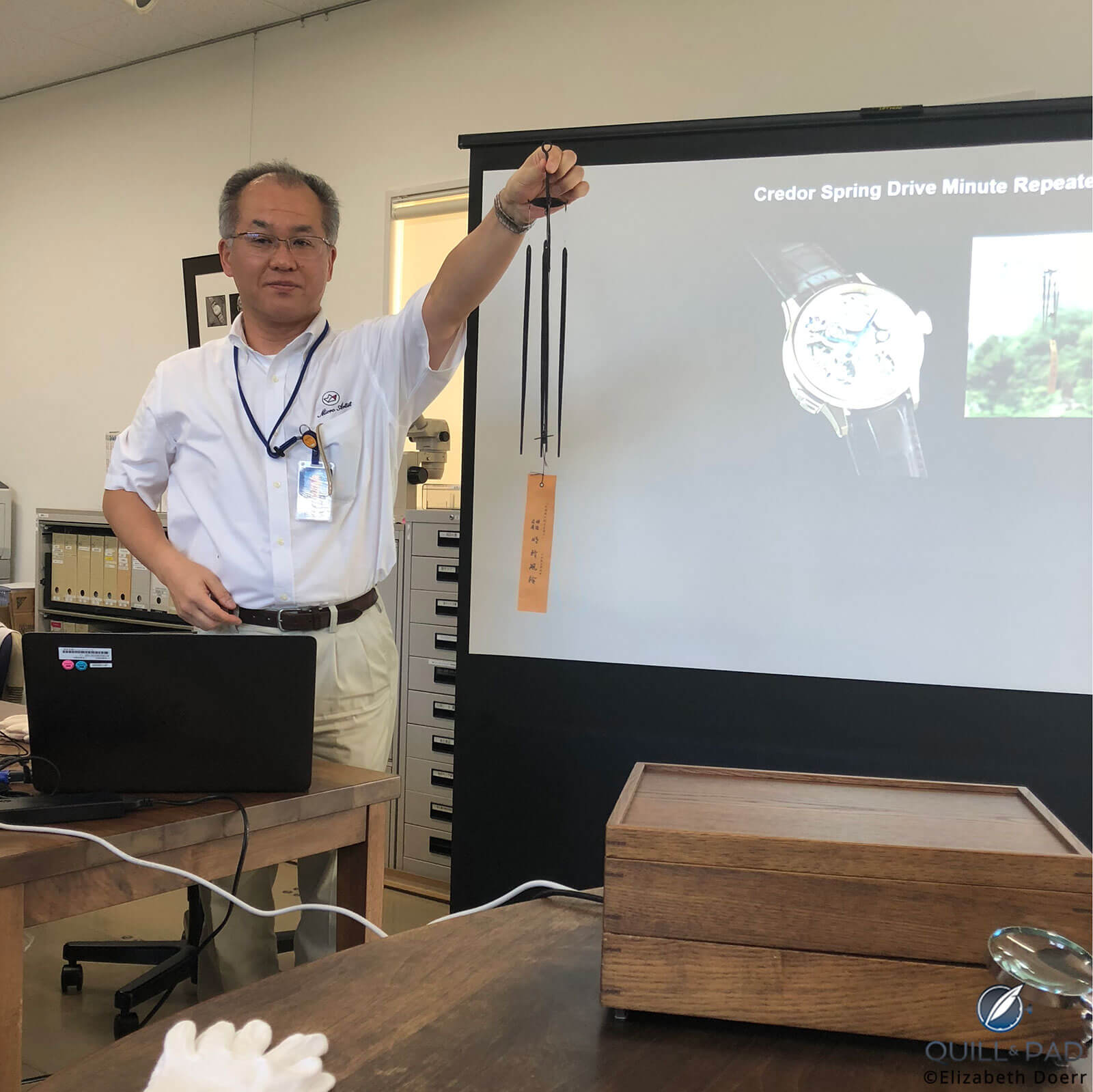

Kenji Shiohara in 2008, demonstrating the sound the orin bell makes

As a result, Shiohara was encouraged to found the Micro Artist Studio in February of 2000. “A high bar was needed; more difficulty, challenge,” Shiohara recalled to me during a trip I took to Japan to see him as I was researching 12 Faces of Time in 2008. “Raising the bar is to improve watchmaking skills.”

Shiohara was alone in the Micro Artist Studio at the beginning. Little by little, though, he found like-minded colleagues: some approached him, and others he approached about joining him in the newly founded department that was allowed free rein. The division is now home to nine artisans.

Ten years later: the author meets up with the now-retired Kenji Shiohara in 2018

Located in Seiko’s Shiojiri factory in central Japan’s Nagano prefecture, the Micro Artist Studio is right next to the division that specializes in the Spring Drive – which is fortuitous, for the Micro Artist Studio uses the Spring Drive movement in its extraordinary creations.

Mentor from Switzerland: Philippe Dufour

Shiohara became greatly interested in the history of mechanical watchmaking, fascinating to him because it was a horological style that allowed a watch to last for generations, and began researching by inspecting vintage mechanical Seiko watchmaking from about 1960. He found that older watches had very durable parts.

“The skill that went into that polished metal contained the condensed wisdom of watchmaking,” he explained to me. “Skilled watchmakers can make watches durable, give them longevity.”

Reading books, Shiohara delved into Swiss-style watchmaking. Inspired by what he was seeing, he wanted to learn from Switzerland. It was thus he read interviews with and articles on independent watchmaker Philippe Dufour, hailing from Switzerland’s Vallée de Joux. Dufour is not only eminently revered in Japan, insiders all over the world consider him a living legend.

Philippe Dufour watches over an artisan in Seiko’s Micro Artist division

Coincidentally in 2002, Shiohara saw a television program that described the small universe of independent watchmakers and then in October of the same year Dufour came to Japan. In an interview Shiohara learned that traditional Swiss watchmaking can extend the life of a watch.

Shiohara felt that he and Dufour were very like-minded and he arranged to meet him. He learned that Dufour’s attitude and way of teaching others watchmaking was not limited to just one culture or way of thinking; a great source of Dufour’s pride is teaching his style of watchmaking to the next generations.

And so it followed that Dufour even visited the Shiojiri factory to impart some of his wisdom in the area of finishing to Shiohara and his colleagues. Finishing, as the Swiss have known for centuries, extends the life of a watch by protecting its components.

Therefore, the Micro Artists now employ some of the techniques Dufour taught them for decorative quality purposes and to achieve the main goal of extending the life of a wristwatch.

Note the exceptional finishing on this movement of the Micro Artists’ Seiko Credor Minute Repeater Spring Drive movement

However, at this point it must be underscored that the Micro Artists, as citizens of the world and intellectual watchmakers, are interested in learning from everyone, but do not wish to imitate. The timepieces that have emerged from this workshop under the name Credor are distinctly Japanese in feel and cultural ties.

Simply put, there is nothing else like them in the world of haute horlogerie.

So while Shiohara, who is now retired, reached his original goal of incorporating haute horlogerie watchmaking into his creations and passing his knowledge on to younger generations, he also succeeded in creating something entirely new and innovative: a set of timepieces realized with the aid of haute horlogerie principles that merge Japanese culture ever so lightly with established European cultures of mechanical watchmaking.

Masatoshi Moteki, movement planner in Seiko’s Micro Artist division, is well-versed in literature concerning Swiss watches and movements

Credor fine watchmaking

The Micro Artist Studio proudly released its first limited timepiece in 2003 to widespread acclaim in the markets in which it was available. The Credor Spring Drive Skeleton, decorated by a Japanese engraver at another of the Seiko factories, was only available in a ten-piece edition plus one unique piece featuring Japanese lacquer. Shiohara and his team credited this watch as a direct result of learning Dufour’s finishing techniques.

Seiko Credor Spring Drive Skeleton (photo courtesy Joe Kirk)

This timepiece was quickly followed in 2005 by the Credor Moon Phase, a lunar timepiece decorated in tones of silver that emits a distinct Japanese feel.

Monochrome, minimalist: the Seiko Credor Spring Drive Moon Phase (photo courtesy Joe Kirk)

But the real hammer was Shiohara’s pet project, released in 2006, which solidified not only the extraordinary will of the Micro Artists, but also their deserved reputation among collectors. Perhaps the most Japanese of the Spring-Driven trio released to that point, and certainly the most complicated, the Credor Sonnerie remains a masterpiece of technology and tradition.

Seiko Credor Spring Drive Sonnerie (photo courtesy Joe Kirk)

In Japan it has traditionally been the sound of a bell emitted by temples that has provided a reckoning of time. The sound of a gong has a special meaning to the Japanese, and the temple gong provides a lingering sound that can cross large distances. Sounds are important to the Japanese.

Knowing this makes the revolutionary movement of the Spring Drive even more meaningful: not only do its hands move in a natural gliding motion, it does not tick. Like planets and orbits, it represents a natural flow of time.

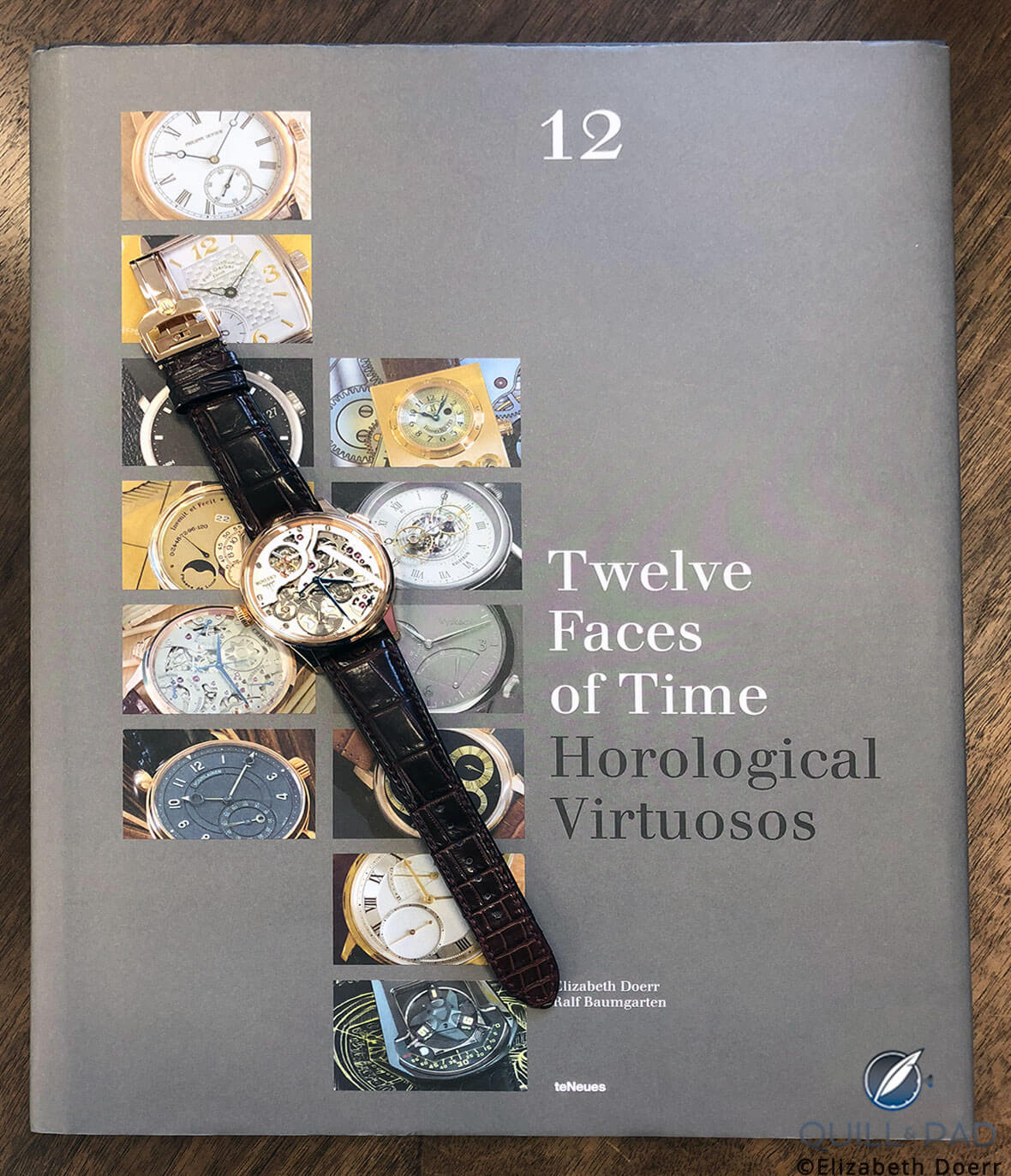

Seiko Credor Minute Repeater resting on the author’s oeuvre ‘12 Faces of Time’

The Micro Artists thus searched for a way to sound the time differently from regular repeaters in a smoother, more relaxing, quieter, and more peaceful way. The thought was to reproduce an orin bell found in Japanese temples set to ring every three hours at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock. No mean technical feat, the lingering sound of the gong within the Sonnerie needed a great number of prototypes to achieve.

The Micro Artists searched for the most “comfortable” interval for the repeater and found that three seconds is the most agreeable length for their ears. The three-hour interval of the Sonnerie is almost the same as that of the temple bell. The Sonnerie can be set to three different functions: sonnerie mode (chimes every hour), “original” mode (chimes every three hours starting at 12:00 as described above), and silent mode.

An orin bell

It was important that this be a watch conveying a sense of peace and quiet with a natural flow of time and Japanese sensibilities. Therefore, it includes some other unique characteristics: since the Credor Sonnerie has no dial to speak of, it is easy to see the placement of the bridges among the 617 components arranged to symbolize a flowing river.

Caliber 7R06’s spring barrel cover, prominent at the 12 o’clock position, is skeletonized to represent a Japanese flower called kikyo. Interestingly, and quite coincidentally, the word kikyo translates as bellflower, a hardy bloom renowned for spiritual healing.

Its three leaves could well symbolize the Sonnerie’s three functions. To perform the Sonnerie’s chiming function, the Micro Artists created a miniature orin bell enveloping the base of the movement, which emanates a clear, pure, precise, lingering sound.

Seiko Credor Spring Drive Minute Repeater

The Credor Spring Drive Minute Repeater followed in 2011, the concept of which was based upon the purity of sound. And it should come as no surprise that this sound is distinctly Japanese in character, achieved by special steel gongs made by Japanese steelmaker Munemichi Myochin, a specialist in wind chimes comprising two or more hibashi tongs.

The repeater’s gongs mimic the sound of a Myochin wind bell, made possible by a unique silent governor that in combination with the soundless Spring Drive allows the gongs to chime the time against a backdrop of perfect silence.

Masatoshi Moteki demonstrates the sound of the Myochin hibashi wind chimes

Additionally, the Credor Spring Drive Minute Repeater is a rare decimal repeater, a far more intuitive system than a traditional minute repeater: it chimes blocks of minutes in units of ten rather than fifteen, just the same way we read them off on a conventional analog watch or clock.

Eichi: Seiko for wisdom

The 2008 Credor Eichi is named for the Japanese word meaning “wisdom.” From the outside it looks very much like traditional watchmaking, down to its finishing. According to the Micro Artists, however, this watch looks to the future – a future evolution of watches that can be used by coming generations.

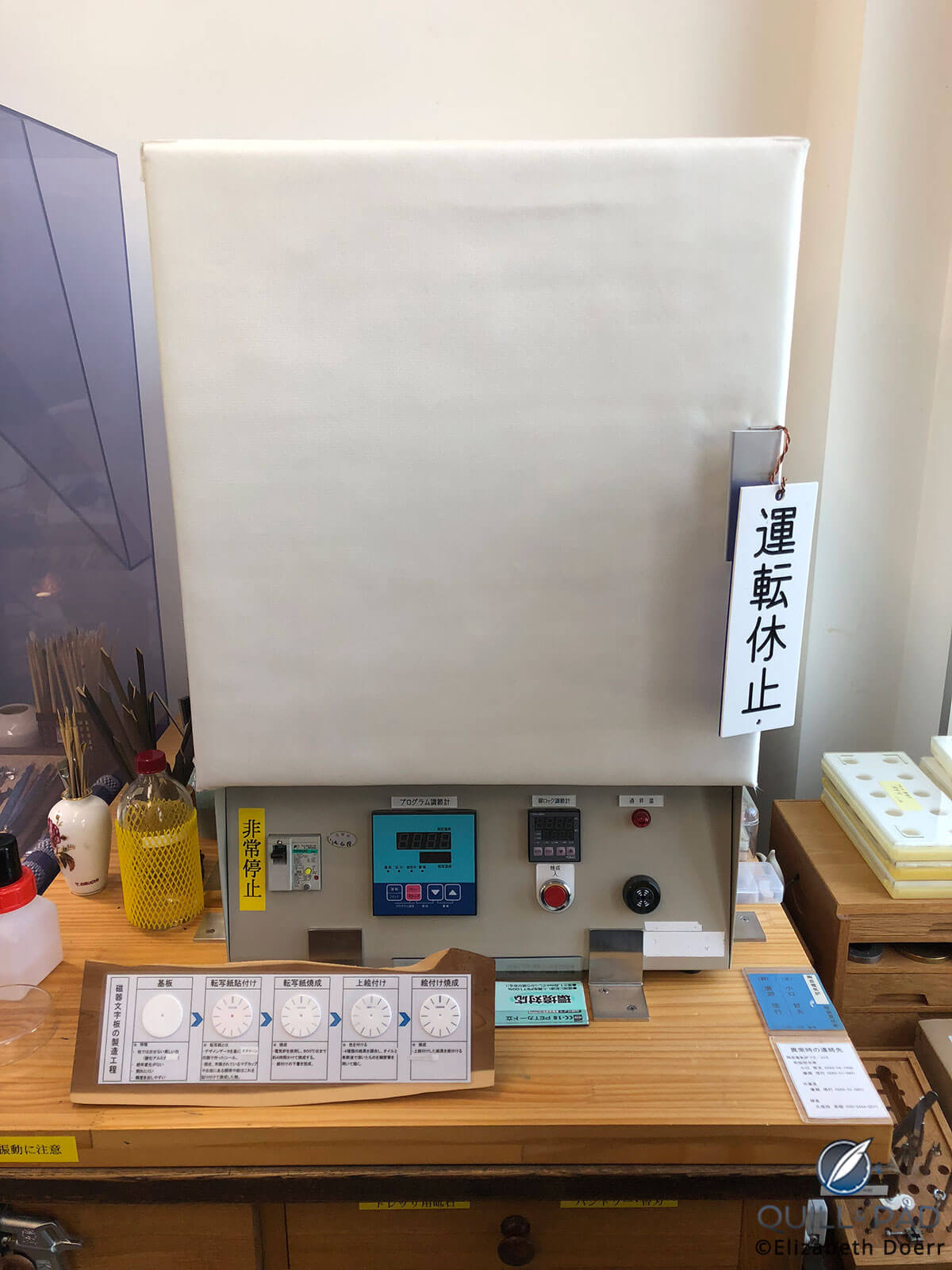

A Seiko Micro Artist painting a porcelain Eichi II dial

Its most obvious element is the porcelain dial made by Noritake, a famous Japanese porcelain maker, while the three highly visible, large bridges are made of untreated German silver arranged in a Japanese shelf design symbolizing cultural asymmetry. The material’s natural yellowish color gives off a warm feeling that pleases its creators immensely, who decided to go with the warm feeling over the scratch resistance that lacquering the metal would have provided.

Seiko and Noritake are two companies with similar elements in their histories: both imported important elements from Europe in their early histories, and both have evolved into technical powerhouses: among other things, Noritake has evolved ceramics for industrial uses in Japan.

Kiln and firing instructions in the Seiko Micro Artist division

The porcelain dial of the 35 mm Eichi – which looks bigger than it is because there is no bezel, which can be thought to symbolize the great power of the Spring Drive – depicts snowy scenery with its pure white color, while the blue color is hand-painted by Noritake craftsmen. The dial’s base consists of aluminum oxide, which makes the porcelain color pure white and helps prevent breakage.

Seiko Credor Eichi II

In 2014, Seiko introduced the Credor Eichi II, an even more more puritanical take on the ideal of the Eichi with a time-only porcelain dial that is crafted right in the Micro Artists’ studio.

Back of the Seiko Credor Eichi II

When you consider that the craftsmen found in the Micro Artist division didn’t learn how to finish movements during their educations, nor was it part of the company culture of Seiko, it becomes apparent what a huge achievement these developments are.

However, above all, one must remember that the finishing on these haute horlogerie wristwatches created in Japan was not applied only for the sake of aesthetics, but also to enhance the watches’ functionality and durability.

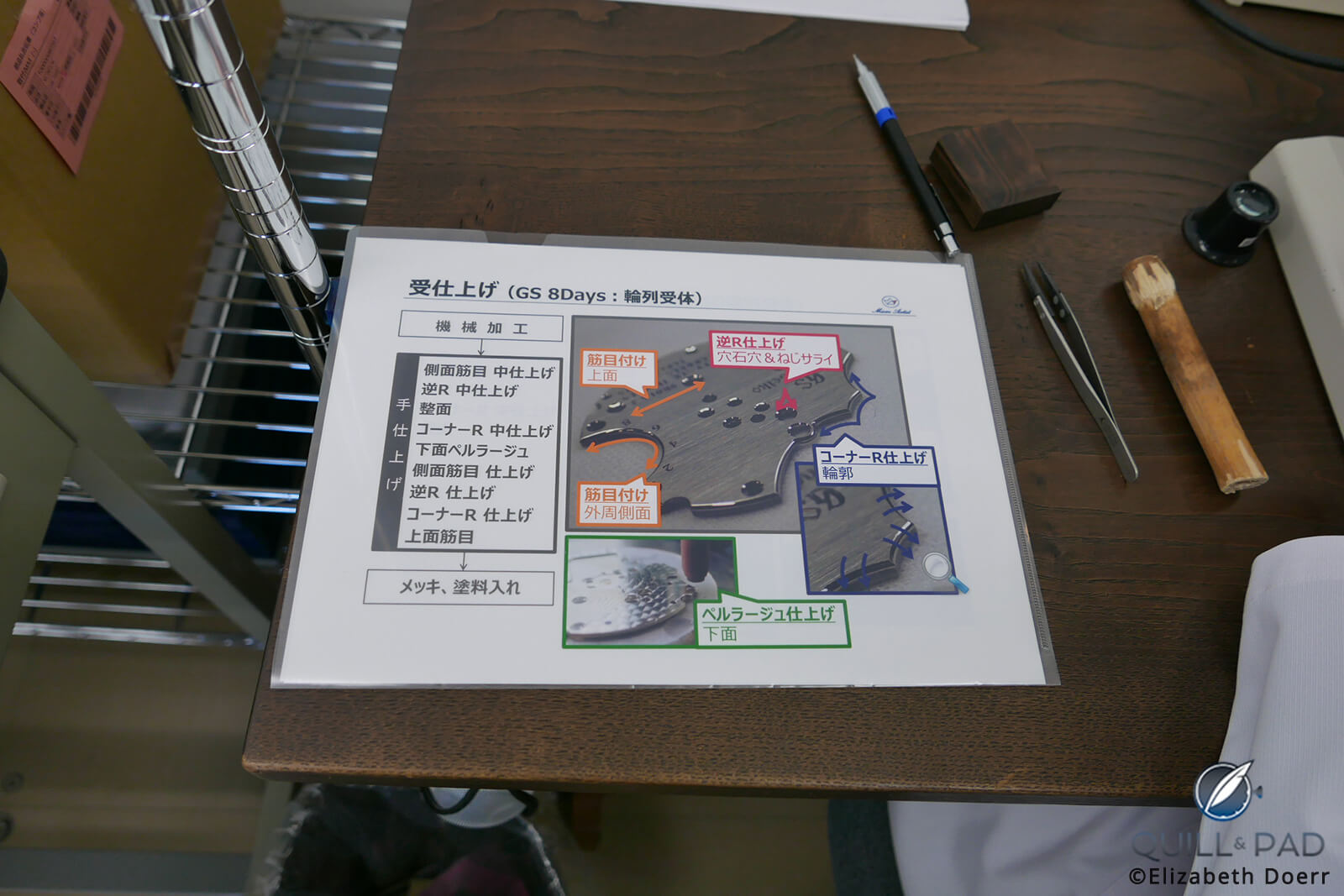

Finishing instructions in Seiko’s Micro Artist Studio

As Shiohara so aptly put it back in 2008: “Decoration is partly necessary, but perfect functioning is much, much more important.”

Credor masterpieces of the Seiko Micro Artist studio

2003: Credor Spring Drive Skeleton

2005: Credor Moon Phase with Spring Drive

2006: Credor Spring Drive Sonnerie

2008: Credor Eichi

2011: Credor Spring Drive Minute Repeater

2014: Credor Eichi II

For more information, please visit www.seikowatches.com.

Quick Facts Credor Spring Drive Minute Repeater

Case: 42.8 x 14 mm, 18-karat pink gold

Movement: manual winding Spring Drive Caliber 7R11 with 72-hour power reserve (without repeater function), 112 jewels

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; power reserve indicator, decimal minute repeater

Price: 35 million yen (approximately $320,000)

You may also enjoy:

Seiko’s Credor Fugaku Tourbillon: A Masterpiece Of Horological Art

Grand Seiko: Already Big In Japan And Getting Bigger Near You

Seiko Celebrates 20th Anniversary Of Grand Seiko 9S Caliber With 4 New Models

Seiko Prospex 1970 Diver’s Re-Creation Limited Edition: It’s Turtle Time Again!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Great read; thanks!

I loved the article, Elizabeth! As a big fan of Seiko, this was an extreme pleasure to read.

A wonderful article thank you.

Thank you for reading!

Thank you for the article. I found the intensity of the creations rewarding. Having been involved with SEIKO over many years, there core timepieces are due reward to their innate skills.