A world-class micro-engineer, industrial designer, metalwork artist and accountant walk into a bar, and the barman asks, “What will you have today, Mr. Gerber?”

Okay, a weak joke may not be the most dignified way to introduce a giant of watchmaking, but the real cognoscenti will know that the punchline is pretty accurate. This was confirmed to me during a brief and – as usual, fun – visit with him and his wife Ruth during an Easter break. Let me backtrack for a minute.

Paul Gerber

Paul Gerber is Bernese by birth, but living and working in Zurich for nearly half a century, he has had his platinum fingers in the mechanism of many a great watch or clock over that half-century plus. Among his global creations is, for instance, the cool-calm-collected MIH watch made for the Musée Internationale de l’Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Two of his pieces have been in the Guinness Book of Records.

One time was for the smallest clock made of boxwood, another for one of the world’s most complicated watches. This latter timepiece was originally a fairly simple pocket watch made by Louis Elysée Piguet in the early twentieth century, but a new owner, Swiss entrepreneur Willi Sturzenegger (the “Earl of Arran”), decided to soup it up (see The Ongoing Saga Of The ‘Superbia Humanitatis’, The World’s Most Complicated Wristwatch, By Louis-Elysée Piguet, Franck Muller, And Paul Gerber).

Gerber also makes watches under his own name: they are easy to read and outfitted with small touches of genius, such as a dizzying triple rotor. It’s Gerber’s understated humor coming out, a necessity for his version of “innovation.”

The calm, cool, collected MIH Watch

At the end of August 2015, I had the great luck to spend a few intense days with Paul Gerber and his wife and comrade-in-arms, Ruth. The occasion was one of his watch seminars, during which two other gentlemen and I were coached by Gerber while we took apart an old Unitas movement, changed the main plate, decorated it, and put the whole thing back together again in a special case.

Easy does it

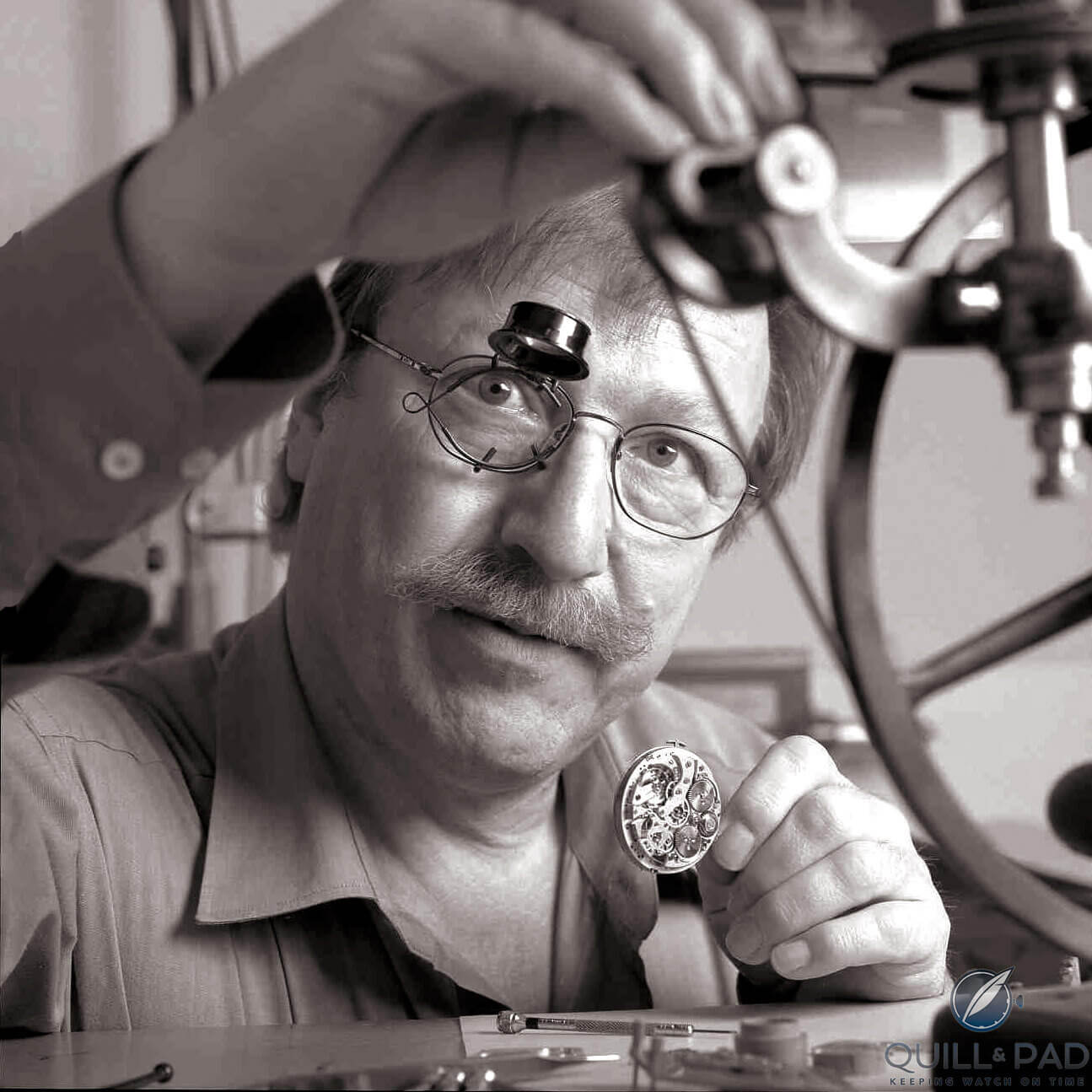

At the time, I had already developed a deep respect for this dyed-in-the-wool watch-genius. Nothing in his surroundings or demeanor suggested the extent of his know-how and experience. He seemed more akin to some regular Joe, puttering around his little den-like workshop in the basement of his modest house on Zurich’s western edge.

But the three-day workshop, aside from deepening my knowledge of the art, was also full of wonderful discoveries, tiny clocks, machines, movements he’d rebuilt, gadgets and gismos, and lever arch folders stuffed with thousands of pages and images fastidiously documenting the work of a lifetime.

We met at various events since, and each time he extended a generous invitation to drop by. Casually. And so, earlier in 2018, I was able to finally take up Paul and Ruth Gerber on their invitation.

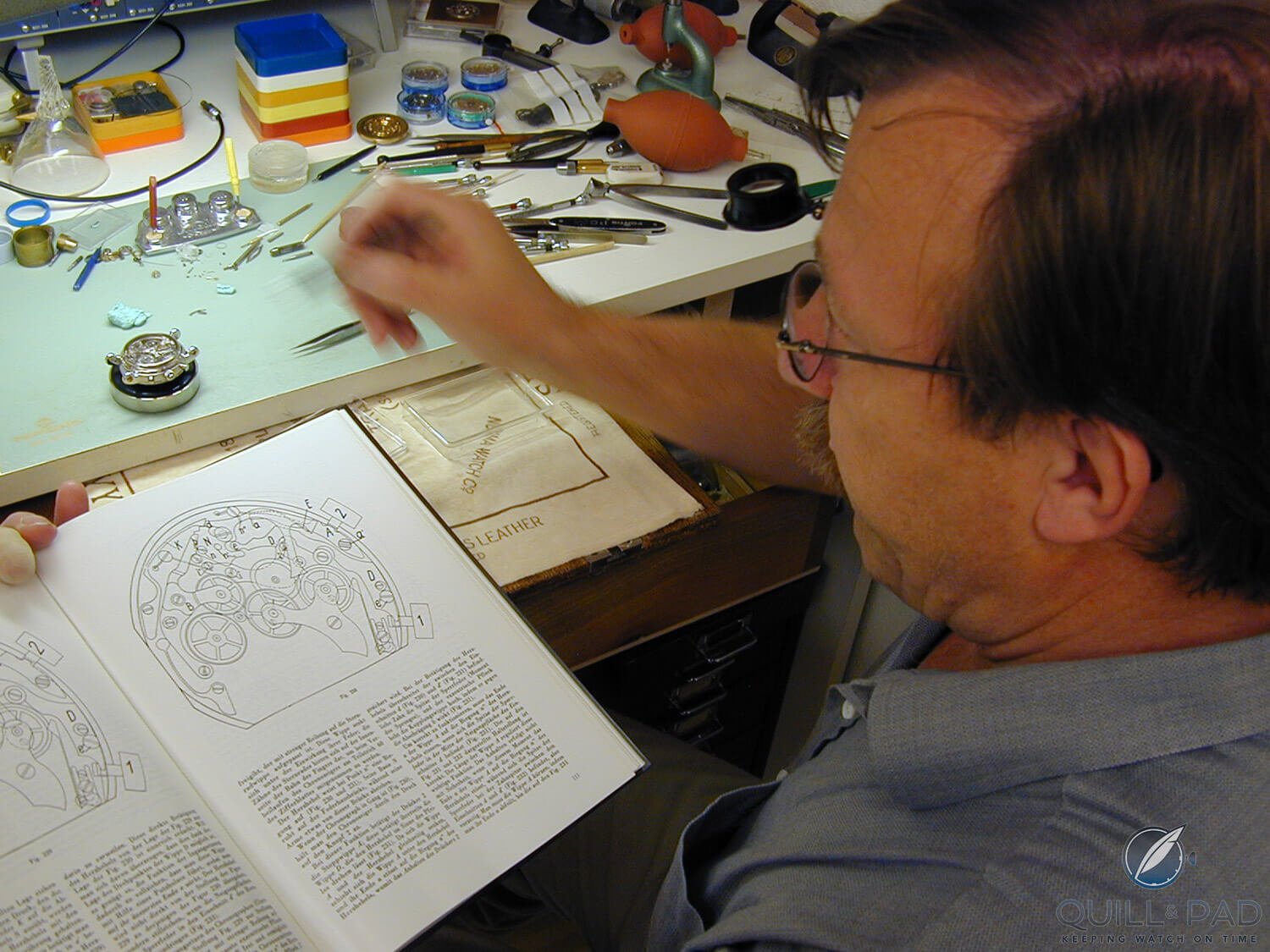

It was a sunny day. But no sooner had I arrived than Gerber took me to his workbench in the den-like basement. The operational word is “work”: the space is covered with motley items he uses to operate on watches: screwdrivers, tweezers, bits of gummy stuff used to pick up tiny screws, a quadruple oil dispenser.

There was also a broken wine glass he uses to protect parts from dust while they wait to be assembled. Most industrial watch workshops have elegant cheese bells. “I’ve had this since I started,” he pointed out with a mischievous smile. Gleefully he showed me a device he’d built . . . just to sharpen screwdrivers. “The others don’t work well.”

But the pièce de resistance was undoubtedly a tiny ring-shaped part of silvery metal, stainless steel I assumed, which he picked up with a pair of tweezers and held up to the light. I had no idea what it was. He explained forthwith: it was the frame of the watchstrap moon phase he’s made for the MIH watch (for more, see 5 Watches By Independent Watchmakers Paul Gerber, Habring2, Struthers, Vincent Calabrese And Christiaan van der Klaauw).

Paul Gerber EPR 52 Micro Moon

The story behind it was typical Gerber: a customer had wanted a moon phase on his MIH watch, and rather than clutter up the dial of the minimalist watch he decided to sink a small, battery-driven moon phase into the strap, an innovative idea if I ever heard one.

Paul Gerber EPR 52 Micro Moon

Discoveries

We were supposed to go out for lunch on this, the first real day of spring in 2018. But I had brought a big jar of mustard and spontaneously suggested it would be a great day to grill cervelat and enjoy the garden . . . Gerber seemed relieved, and I was too. Ruth immediately set about organizing the lunch, while Paul disappeared somewhere to grill the sausages.

Chatty aside: is there any Swiss family that doesn’t keep an emergency reserve of cervelat, that short, thick wiener-like sausage wrapped in natural skin? It caused a bit of a stir about eight years ago when it seemed Switzerland was running out of skin. I guess not.

Over lunch, Gerber talked about his early days in the biz. The quartz crisis was raging at the time he was doing his apprenticeship. And so he began by opening a watch and jewelry shop.

As he spoke, I had difficulty imagining this brilliant watchmaker discussing watch straps with walk-in customers or confirmation gifts for thirteen-year-olds. And he confirmed my feeling: being in his watchmaking den, with his fingers on the wheels, was more along his lines. He sold the shop.

Model 42 by Paul Gerber with vivid green elements

Child’s play

A distant connection of sorts flash through my mind. Gerber’s enthusiasm with watchmaking reminds me of a sentence MB&F founder Maximilian Büsser has made into his company’s tagline: “A creative adult is a child who has survived.” Survived the constraints, strictness, rigidity, Gradgrindish goal-setting of the so-called adult world.

This explains his desire to stay close to his work, at home in his basement, rather than delve into the flimflam of communication and publicity. The marketing masters of our industry love to talk about passion and urge their copywriters to “do emotion.” But Gerber does not perceive and then act in the spirit of passion (conjuring Hume here), he just lives it as a cellular impulse. His rationality then steps in and tells him how to implement it in the three-dimensional world.

Paul Gerber’s improved watchmaker tweezers

I mention a young unemployed watchmaker I know, who has restored some surprisingly valuable watches (an Omega Seamaster among others), and the conversation drifts towards old movements and replacement parts. You’d think it is extremely esoteric and a little dull, but it’s not. Not when Gerber talks about it.

It’s more like Wilhelm Kempff talking about piano strings or felt hammers. And so I learn that watchmakers who’ve started cranking a heavenly topping tool often leave a treasure trove of bits and pieces, sometimes even entire movements, for the next generation. These end up in flea markets or are picked up by other watchmakers to fiddle around with.

And are then passed down or end up in a special timepiece that may or may not be sold. More likely than not, it will end up in the recycling container. Gerber has his own collection of composants trouvés, as it were.

Hobbies

I thought his big hobby was fly-by-wire planes . . . But after lunch, Gerber steers me to a display case in his living room containing one of his own collections. Standing on a shelf like little soldiers is a battalion of old Oris travel alarm clocks, the ones that folded up into a hard shell, a clever design.

Just for the heck of it, he built a functioning tourbillon into one of them. At some point, virtuosity is the key that unlocks total creativity, sort of like Picasso drawing Gertrud Stein as graffiti on a bathroom wall.

Paul Gerber’s restored 1950s Fiat 600 Multipla

He had more to show me, down in his Ali Baba cave, “The Basement.” Bellies full, we browsed through pictures of his special car, a Fiat 600 Multipla from the late 1950s, adoringly restored. Interesting: many watch aficionados I know have flashier vehicles, but this one has personality. Gerber pulled out some mechanical place-name holders that show the diner’s name when a lever was depressed.

I asked him about the amazing Earl of Arran watch, and he dragged me back to where I had sweated for three days two years earlier decorating that Unitas movement, where we found a large and beautiful box with a leather insert.

The Superbia Humanitatis watch created by Louis-Elysée Piguet, Franck Muller, and Paul Gerber (photo courtesy Dr. Magnus Bosse)

Back in the basement, he shows me the large gear wheels he finished for one brand we shall keep anonymous. He dismisses the actual model they were fitted into with a sly, deprecating smile. But those gear wheels . . . beveled to perfection, inside and outside edges, including the corners, which are exceedingly tricky, the three wheels displaying 40 (!) surfaces for his rock-steady file to transform from mundane metal to watchmaker perfection.

And that for several models. He also pulls out a thick folder to show the details of the order. Everything is documented, beginning with sketches and down to the last screw. That’s the book-keeping part. It’s a key to maintaining continuity; it’s a gift to future generations.

I think full circle. When I first left Gerber’s cavern a few years back, I thought hard on what elevates some watchmakers to the highest rank. It’s not just the achievement and portfolio. The challenge is this: watchmaking taps into all sorts of fields. In addition to engineering, material science, gem setting, and enameling, a top-notch watchmaker will know history, navigation, astronomy, theology, philosophy, and aesthetics.

Paul Gerber was the expert watchmaker of choice to realize Lord Arran’s desired enhancements on the Superbia Humanitatis watch (photo courtesy Dr. Magnus Bosse)

They are Renaissance people, they are the great (sea) explorers, to borrow a term from Richard Buckminster Fuller, who required “. . . great anticipatory vision, great ship designing capability, original scientific conceptioning, mathematical skill, (. . . ), able to command all the people in their dry land realm in order to commandeer he adequate metalworking, weaving and other skills necessary to produce their large complex ships.” (Buckminster Fuller, R., Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, A Dutton, New York, 1963, p. 17)

Reference 33 Mond by Paul Gerber

The era of the master visionary and maker may be dead and gone in many other industries, but to create a beautiful watch, like composing a beautiful string quartet, you need a Beethoven, a Haydn, or a Brahms, not a committee of brainstormers dreaming up target groups. Gerber is up there with the giants.

* This article was first published at The genius of Paul Gerber. It has been republished with permission.

* This article was first published on Quill & Pad on September 12, 2018 at Paul Gerber: Renaissance Man And Creator Of World’s Most Complicated Watch And Smallest Wooden Clock.

You might also enjoy:

The Ongoing Saga Of The ‘Superbia Humanitatis’, The World’s Most Complicated Wristwatch, By Louis-Elysée Piguet, Franck Muller, And Paul Gerber (With Video Of It Striking Time)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!