by GaryG

It seems like only yesterday that I was heading for New York to attend Patek Philippe’s Grand Exhibition there. In fact, it was more than two years ago, in 2017 – and so when the brand announced that another, possibly even grander, exhibition was to take place in Singapore this year there was no doubt that I would do my best to attend – and to convince some friends to come along and join the fun.

Special sauce: Patek Philippe Reference 5930 World Time Chronograph, a limited edition of 300 for Singapore, 2019

A butt-numbing 17-hour flight from San Francisco later, we arrived on a Thursday evening and quickly made our way to our (and the exhibition’s) home for the week, the Marina Bay Sands Hotel and Sands Theater and Shops.

Marina Bay Sands complex at night, complete with laser light show

The following day, we made the first of our two scheduled visits to the exhibition; while admission was free to the public, the organizers wisely required attendees to sign up for specific entry time windows to keep the volume of visitors manageable. We must have picked a good time as our first entry coincided with the arrival of industry legend and Patek Philippe enthusiast collector Jean-Claude Biver.

Jean-Claude Biver (center) with host Michael Tay (to Biver’s right) and members of the Hour Glass team

The spacious lobby you see in the photo above was a pleasant feature of this year’s exhibition, providing room to chat with friends as well as review the pieces of event-related literature for sale and see some fine handcraft pieces from earlier years in the small white booths visible at the right.

After chatting briefly, we made our way through the red-backed opening you see at the rear of the photo and into the main exhibition areas.

Once inside, we were directed through a set of rooms whose themes were familiar to us from the New York exhibition containing pieces from the current Patek Philippe product line, historic pieces from the Patek Philippe Museum, an entire room devoted to watch movements, unique and limited edition watches made for the Singapore exhibition, and demonstrations of both fine handcrafts and watchmaking.

Geneva on the Straits: a recreation of the interior and exterior views from the Patek Philippe Geneva Salon

My friends and I are already quite familiar with the current main-line Patek Philippe offerings, so we devoted most of our time to the important historical watches, handcraft exhibitions, and fine art timepieces on display.

We began with what was described as the most extensive display of historic timepieces ever to leave the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva. Although I’ve been to the museum several times, there were a number of watches on display in Singapore that I don’t recall having seen before; and as an added bonus, photography – which is officially prohibited at the museum – was very much encouraged in Singapore.

Deck watch by Ferdinand Berthoud ca. 1805 and half-quarter dumb repeating chronometer by John Arnold, 1782

My favorites included the side-by-side display, shown above, of timekeepers by legends Ferdinand Berthoud and John Arnold. I also enjoyed the extensive display of watches and decorative items originally for the Chinese market, including a display case that contained three pieces made between 1790 and 1820 for the Chinese market: a combination telescope and watch, a “Lazy Tongs” telescopic hand watch, and a pocket watch with a coiled chain motif.

Telescope and three watches made for the Chinese market

Several exhibits paid tribute to the tradition of paired watches made for the Chinese market, including a pair of musical automaton watches on the theme of The Madonna of the Chair with movements by Piguet & Meylan and gorgeous enamel work attributed to Jean-Abraham Lissignol.

Madonna of the Chair automata as seen at the Patek Philippe Grand Exhibition

A final piece in the “Antique Collection” section that I found both visually striking and historically interesting was the Swiss Federal Rifle Championship watch shown below. This particular watch, awarded to the winner of the 1844 competition, commemorates that year’s 400th anniversary of the battle of St. Jacob with a vivid illustration of the battle scene, the flags of the eight cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy at the top, and the names of the commanders fallen during the battle listed on the scrollwork at the bottom of the case.

To my eye it’s a beautiful watch, and it also keeps the memory of this important moment in Swiss history alive.

Swiss Federal Rifle Championship watch, 1844

All of that, and we hadn’t even made it through the timeline to the founding of Patek Philippe!

Once we entered the “Patek Philippe Collection” area of the exhibit, we were treated to marvels including Antoine Norbert de Patek’s personal pocket watch, a movement from 1842 incorporating Jean-Adrienne Philippe’s first keyless winding and setting mechanism, and the first Patek Philippe wristwatch, a ladies piece from 1868 that was also displayed in New York in 2017 (see it in Give Me Five! 5 Unanticipated Exhibits At Patek Philippe’s Art Of Watches Grand Exhibition In New York).

It was also a treat to see once again the earliest known perpetual calendar wristwatch, based on a pocket watch movement partially completed in 1888-89 and finished in 1925 for inclusion in this watch.

The first perpetual calendar wristwatch, completed in 1925 by Patek Philippe

My eye was especially drawn to a set of later grand complication pieces from between 1910 and 1947, seen below. The piece on the right, originally made in 1930 and enhanced with the calendar and moon phase indications between 1945 and 1947, has the early 1940s Patek Philippe aesthetic that I particularly love, with small applied Arabic numerals and champlevé enamel indications.

Three Patek Philippe grand complication pocket watches made between 1910 and 1947

We spent much of our remaining time during our first visit talking with, and watching, the craftsman responsible for making all of Patek Philippe’s intricate wood marquetry watch dials and cases, Jérôme Boutteçon.

Jérôme Boutteçon demonstrates and discusses wood marquetry techniques

Boutteçon began his woodworking career in a conventional way making furniture and other large objects, but then became fascinated with the idea of applying marquetry techniques to smaller and smaller objects until he arrived at watches. He has been working with Patek Philippe on marquetry dials and cases for ten years – and for the past four years exclusively.

Patek Philippe Reference 997/104J marquetry pocket watch Arowana Fish and Water Lilies

The results are breathtaking, as seen in the pocket watch case featuring a dragon fish swimming through a field of water lilies, detailed to the point at which we can see the tiny bubbles escaping from the fish’s mouth and bubbling toward the surface.

As always with expert craftspeople, to discuss is to learn! Boutteçon was kind enough to share many details of his technique: for instance, once the patterns for the desired marquetry image are drawn they are cut out and each piece of the pattern glued to a sandwich of colored wood with as many layers of wood as the number of watches to be made. He then uses the foot-powered saw you see in the earlier photo to cut all of the pieces needed at once, ensuring consistency.

Parts for five elements of a series of ten marquetry watch dials

The result is a tray filled with hundreds of small piles of elements of the wood mosaic, a subset of which is shown above. But what’s with the printing? We learned that each layer of the wood sandwich is backed with a layer of newsprint, which has ideal characteristics as a substrate for this work: its random non-woven fibers keep the grained wood from splintering under the pressure of the saw, and its loose weave makes it easy to wash off once the sawing process is complete.

Patek Philippe Reference 992/118J marquetry Junks pocket watch

At the next station, we watched a craftsman create guilloche patterns with a rose engine, and at another an artist demonstrated enamel painting techniques.

Enamel painting demonstration, Patek Philippe Grand Exhibition, Singapore

Used together, these techniques created my favorite new watch of the event: Reference 992/153G “White Tiger.” The ripples in the water are guilloche beneath translucent blue enamel, and the tiger and vegetation were hand-painted and fired in 18 separate cycles. I love everything about this piece, but first and foremost could spend hours considering the way that the tiger is “reflected” in the water as he crosses from rock to rock.

Patek Philippe Reference 992/153G ‘White Tiger’

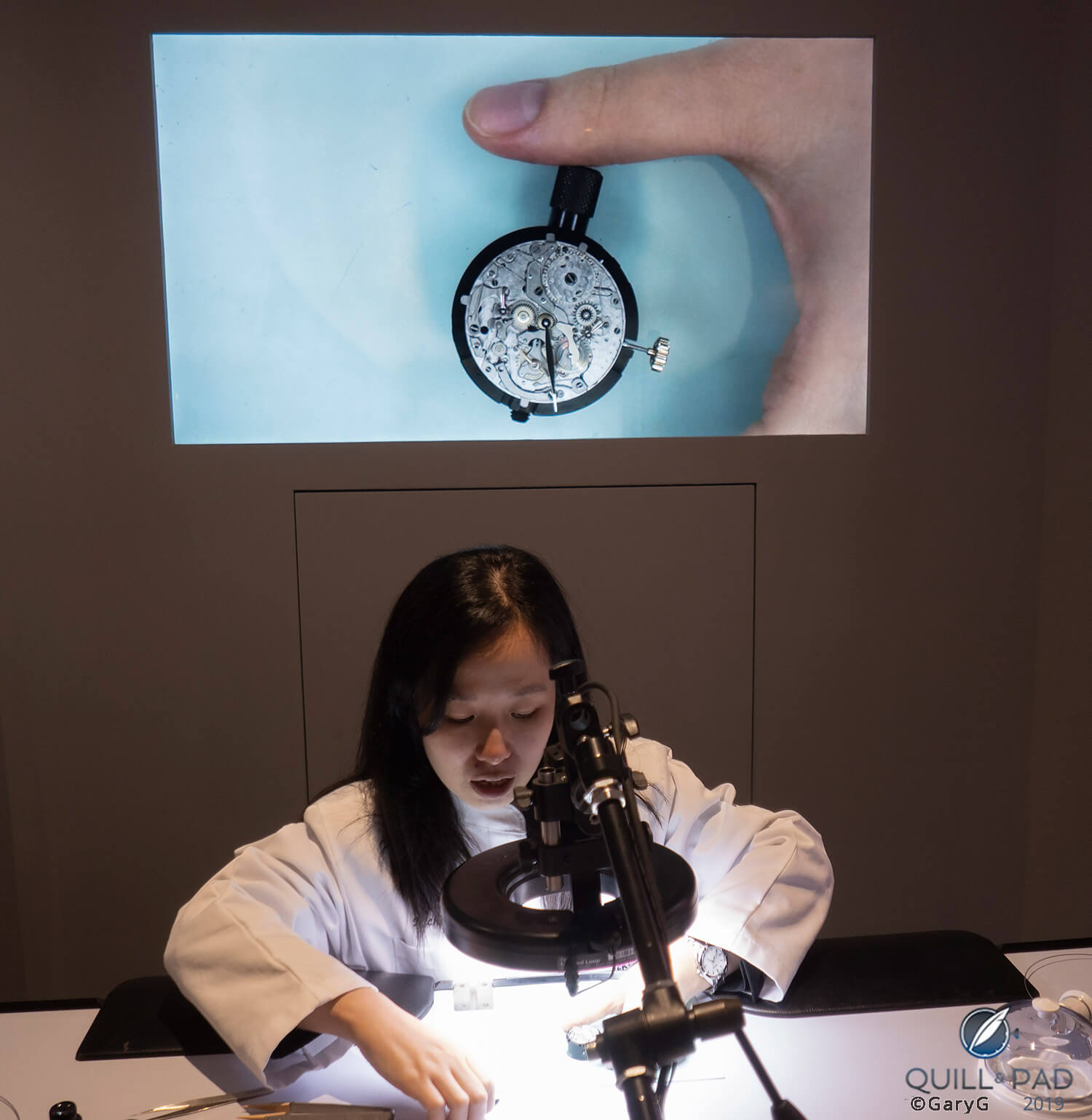

After a brief visit to the room in which all of Patek Philippe’s current movement calibers were on display, we made our way to the tables at which watchmakers were explaining the functions of movement components and complications including automatic winding, minute repeaters, and the perpetual calendar.

It’s one thing to read about how the 48-toothed wheel controls month length in a perpetual calendar, but quite another to see how the movement components interact at the end of each month, including at the leap year, to advance the date to the first of the following month.

Perpetual calendar demonstration, Patek Philippe Grand Exhibition

On our second day, we did a bit of watch shopping (without denting our wallets) and explored the city – but the exhibition was never far from our consciousness.

I certainly have to give the show organizers credit for actively promoting the event; I’m not sure that strolling sandwich board wearers would be effective anywhere else in the world, but in watch-crazy Singapore I’m guessing that they stimulated more than a few visits.

No stone unturned: sandwich board solicitors along Orchard Road

We also took the opportunity to meet up with long-time Singaporean collector friends to catch up, swap tales, and check out each other’s watches. It’s all about the people!

Six collectors walk into a (coffee) bar . . .

A second, more leisurely, visit on the third day of our trip gave us the opportunity to see some items we’d missed before, enjoy detailed commentary by a staff member from the Patek Philippe Museum on some of the historical pieces, and debate the merits of the various unique and limited-edition fine arts pieces and Singapore Special Edition limited series.

You need this one: watch pals discuss the Singapore Special Editions from Patek Philippe

While for me the exhibition was mainly about the rare handcrafts, historical watches, and artistic techniques, I did rather like two of the special edition pieces. The Reference 5930 World Time Chronograph shown in the opening photo of this article looked much better in person than in the early images I’d seen prior to arrival in Singapore; the dramatic degradé effect tapering from red to black really makes the watch pop in a way that the original blue-dialed version does not.

I was also quite impressed by the Reference 5303 Minute Repeater Tourbillon with its open dial.

Some Patek Philippe loyalists were dismayed that this watch reveals the underside of the tourbillon cage through an aperture on the dial side, and others pronounced the piece’s hands to be “too Ulysse Nardin.”

But from what I could see I’m a big fan. My only complaint was visibility; sadly, this watch and several others in the display were shown in harsh lighting from above that made seeing, let alone photographing, them somewhere between difficult and impossible.

Patek Philippe Calatrava Reference 5089G-085: orchids with cloisonné enamel and miniature painting on enamel

For me, the soul of this exhibition was in its name: Watch Art. I’m somewhat dismayed that so much of the discussion about the show has centered on the small number of special edition pieces and whether a given individual will be able to obtain one, and if so whether its value will increase.

I found it completely sufficient to see and understand what the exhibition revealed about the history of watchmaking and its artistic crafts and am delighted that Patek Philippe went to the substantial effort of mounting this fourth edition of the exhibition.

Before leaving town, we did take time to visit the city’s Gardens by the Bay, which features both unbelievable floral displays and an indoor Cloud Forest with a walkway that winds seven levels from top to bottom.

About to get foggy: Cloud Forest, Gardens by the Bay

In the Flower Dome, we saw many of the flowers that inspired the “Orchids” and “Portraits of Flowers” enamel-dialed watches that Patek Philippe created for this event.

As our visit drew to a close I was left with a real appreciation for the role that Patek Philippe has played in developing the watch industry, preserving the industry’s heritage, and fostering not only watchmaking but also a diverse set of artistic crafts that its timepieces display at the highest levels.

Parting shot: Flowers at Gardens by the Bay, Singapore

Disclaimer: the author paid for his own travel to and accommodation in Singapore to visit the exhibition.

You may also enjoy:

You Are There: Patek Philippe (And Virtually Everyone Else) Comes To New York, A Collector’s View

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

While I often find Patek’s Metiers D’Art wristwatches play second fiddle to Vacheron’s, their decorated pocket watches are second to none. The guilloched pattern coated with translucent yellow enamel on the dial of the 992/118J Junks is mindblowing, in addition to the beautiful river reflections on the back. What a thing.

I agree with you — in particular I’m a big fan of Vacheron’s openwork pieces but when it comes to pocket watches Patek is way ahead!

Best, Gary

Amazing Thank You for sharing this awesome post.Really amazing

My pleasure, John — glad you enjoyed it!

Best, Gary

Mindblowing Thank You for sharing this amazing article,

Really nice.

Happy to do it — it was a fantastic experience!

Best, Gary