by Ken Gargett

Great cognac is spirit royalty. And while cognac is far from a dying art, it is likely that we will not see too many new houses joining the elite producers any time soon. The reason is simple: time (and money, of course).

Great cognac takes time. Decades of it. It is not like gin where you might decide on Monday that you’d like to make gin, and by Friday you are halfway there. From the still the to shelf in weeks is not for cognac.

In addition, whereas it seems that gin can be made from an extraordinary array of different things (motorcycle parts, really?), cognac comes from defined vineyards, and they are not all equal. The good stuff comes from the bullseye in the appellation in France.

It means that the major players are largely ensconced – they have been for decades or even centuries – and while we will continue to enjoy their finest offerings, there are not that many new discoveries to be made.

There is one venerable old house with a history dating back into the 1600s that seems to fly under the radar: the house of Delamain. This seems to be because it is considerably smaller than some producers and because it has not indulged in the ornate bottles and peacock plumage in the way some have.

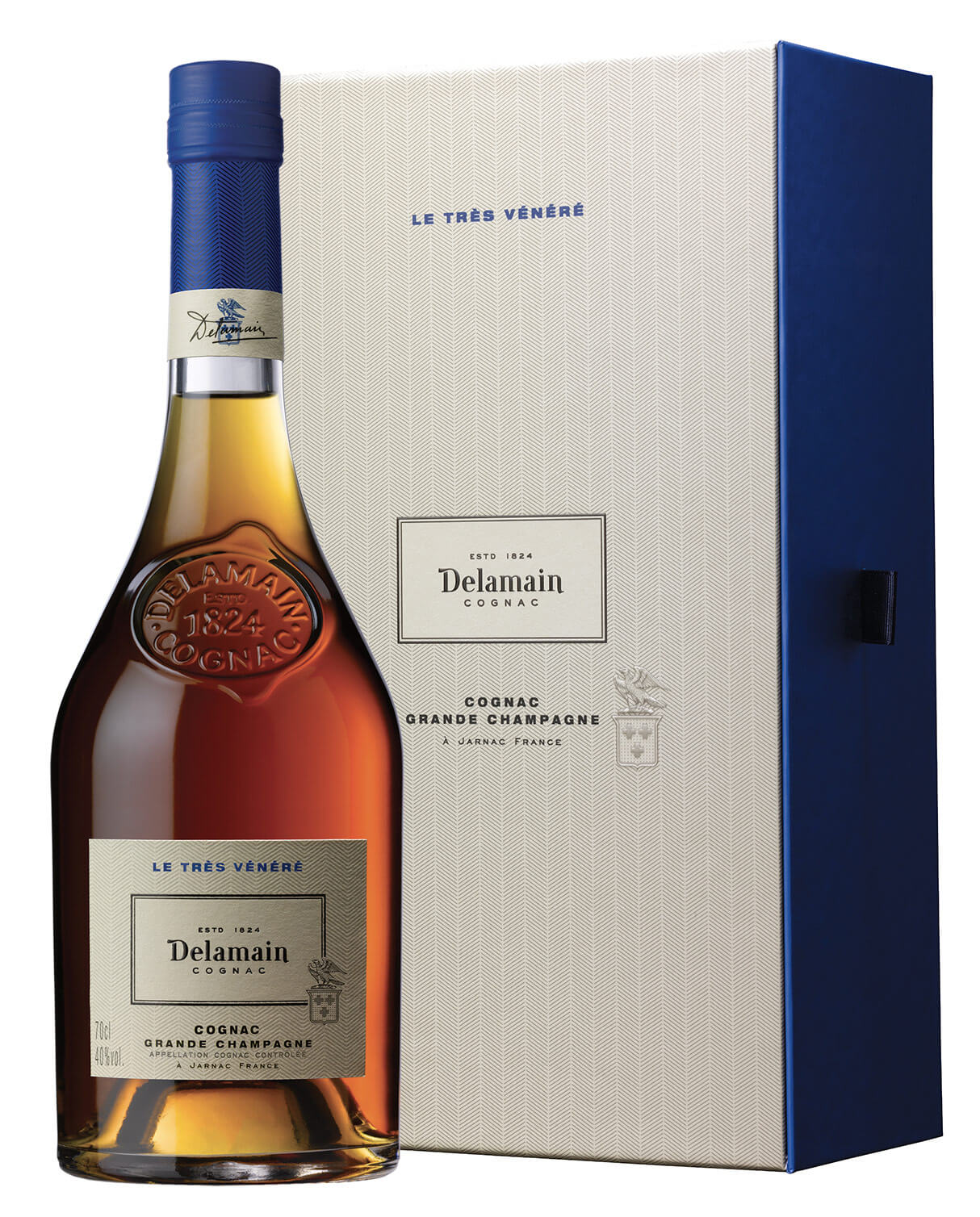

Delamain Le Très Vénèré cognac

That does not mean that it is not the equal, or indeed superior, to many others. This is a house that concentrates, first and foremost, on quality contents. Hard not to love that.

Indeed, it looks to avoid such mundane offerings as VS or VSOP and begins its range with an XO, a cognac aged for 25 years. It also offers vintage cognacs, though these are usually at least 30 years of age.

Delamain has released years such as 1963, 1966, 1973, 1976, 1977, 1980, and 1986, though usually in tiny quantities – around 150 to 200 bottles.

Short history of Delamain

When one says “1600s,” it is perhaps a little flexible and depends on how one wants to measure these things. Jean-Isaac Ranson came from a family that had operated an export business, trading in cognac (one of the first to do so). In 1762, his daughter, Marie, married an Irishman, James Delamain.

James had French roots. His ancestor, Nicolas Delamain, escaped France and the Protestant reign of 1625, fleeing to England. He later received a knighthood from Charles I. He was then, as one said back in the day, “appointed to Ireland.”

James, was only 21 when he headed across to France in 1759, found himself in Jarnac, and joined Ranson’s family firm. He was, unsurprisingly, given the Irish market.

As mentioned, James married Marie in 1762. At that time he was elevated to partnership status, and the name of the firm was changed to Ranson & Delamain.

It was a firm, however, reliant on the efforts of the founder, and after his death in 1800 it soon collapsed. The French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, the Continental trade blockage, and the fact that James and his son, Jacques, could not stand each other, did not help.

Throw in those pesky, and still existing, French inheritance laws requiring equal division of property – James had seven children – and the entire thing was a mess.

The house was revived in 1824 (some internet reports claim 1924, but this would seem to be a small typo if your definition of “small” equates to a century – every bottle confirms 1824).

It was James’ grandson, Anne Philippe (possibly not the most traditional male name) and his cousins from the Roullet family who got the firm back on its feet. It became Roullet & Delamain and remained so until 1920 when members of the Delamain family purchased the Roullet shares.

It then became, as it is today, Delamain & Co. A Delamain is in charge, but the house is owned by the esteemed champagne producer Bollinger. Quality family firms do tend to attract similar operations. And there are very few family houses still operating in Cognac.

The house does not own a single vine, preferring to purchase top eaux de vie from the premier cru of the region, Grande Champagne. Delamain samples around 400 contenders every year, on average selecting just 40 of these for use by the house.

Delamain cognac tasting notes

The notes are based on a recent tasting of the XO Pale & Dry, while the XO Vesper and Extra Dry are from a slightly more historical perspective, though I am assured that that, as one would expect, there has been no change.

Prices are, shall we say, in flux given various tariff issues that seem to have been avoided for the moment, though who knows what the future holds. Suffice to say that the XO Pale & Dry is around AUD$140; the Vesper closer to AUD$180, and the Extra around twice that.

Delamain Pale & Dry cognac

The XO Pale and Dry was created in 1920 (same time as the Trés Vénèré – which has a similar price tag as the Extra, but seems even harder to access). At least 25 years of age, it is a pale gold color.

There are spices, nuts, a note of blueberry, hints of leather, stone fruit, and a warm heart. Excellent length, a little fiery and very complex, this is a first-class cognac (94).

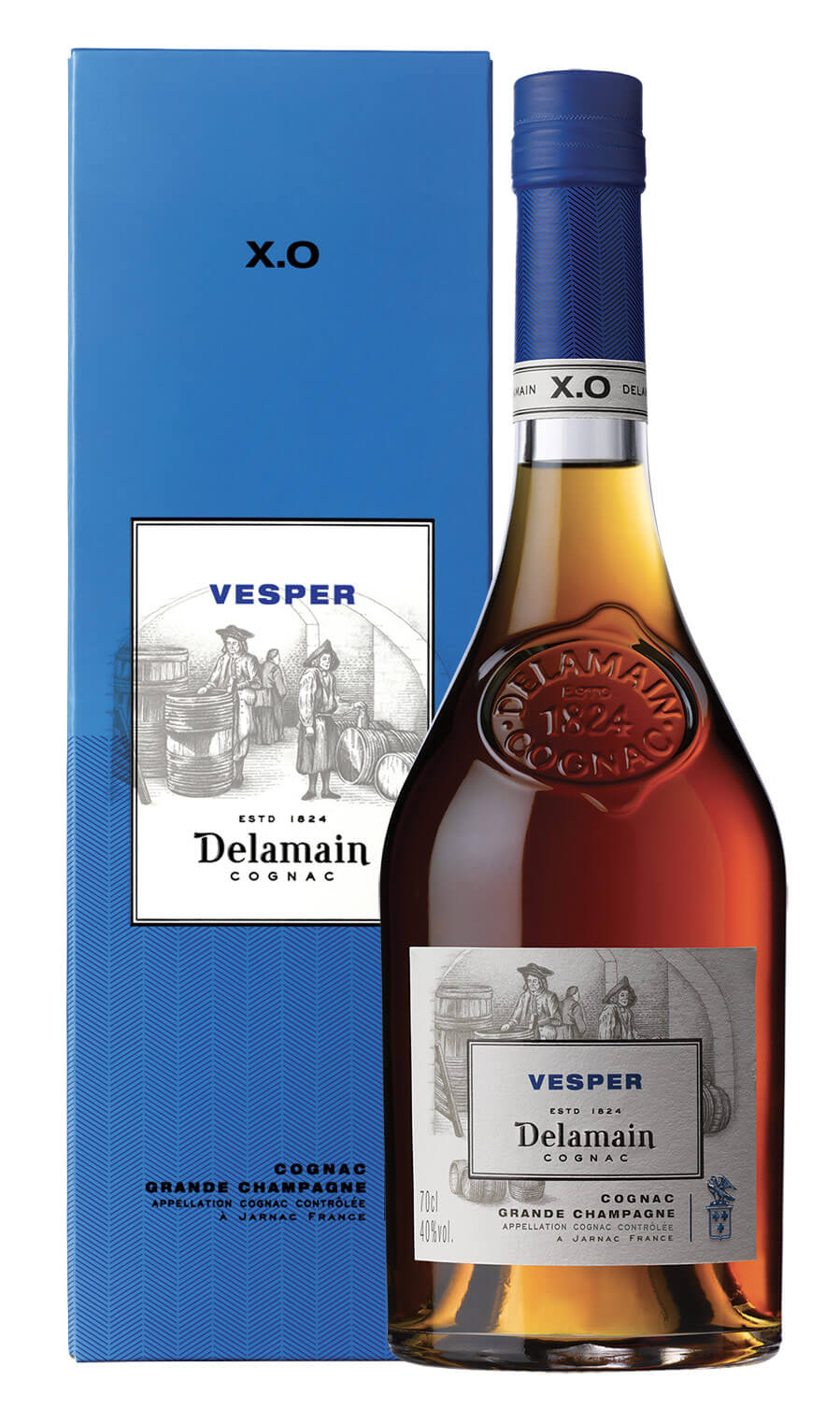

Delamain Vesper cognac

The XO Vesper, created in the 1950s, is a darker color with notes of ripe honeysuckle, caramel, and white chocolate. Black cherry flavors open, but they morph into a chocolate-cherry character. Around 35 years of age, it offers great length and is an utterly delicious cognac (96).

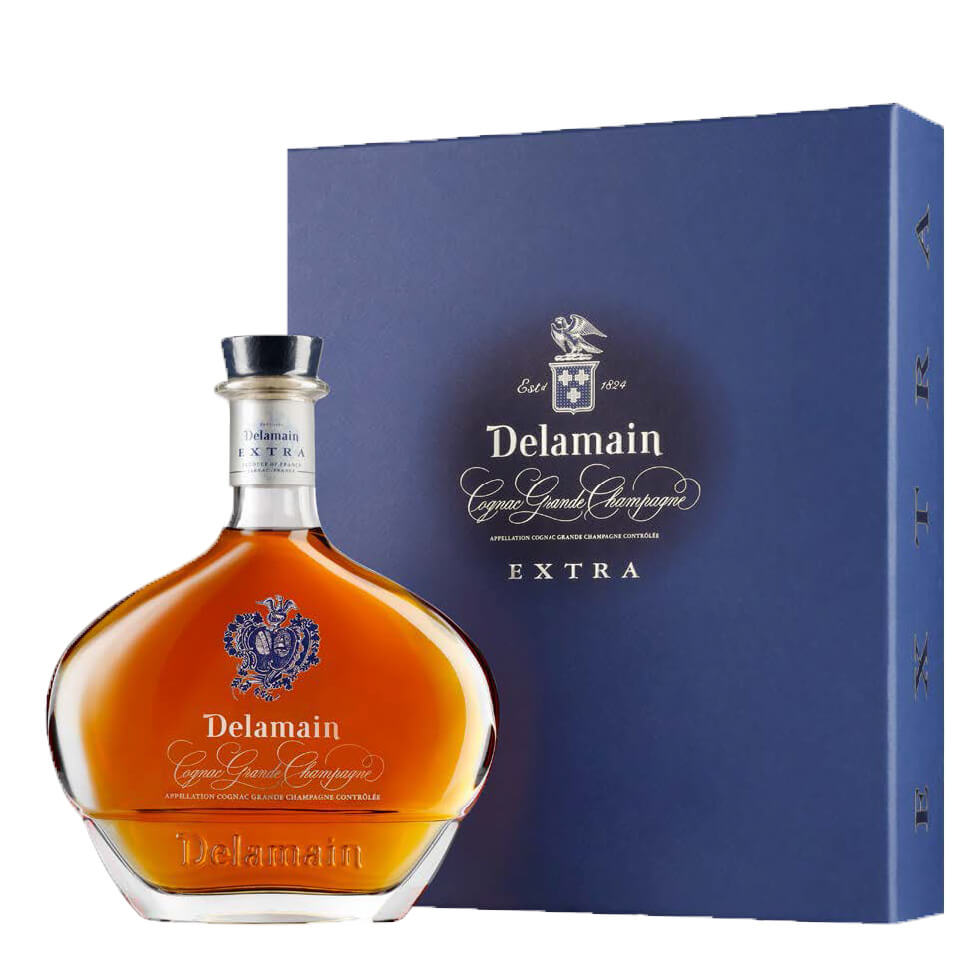

Delamain Extra Cognac

Finally, the Extra Cognac, created in 1976. Older than the other two, though just how old is information kept to Delamain, it is stunning stuff. A pale gold color, though not as pale as Pale & Dry, with cinnamon, spices, honey, vanilla, touches of lanolin, and cedar. A supple, seductive texture. Just enough fire with a very long and complex finish (97).

This ancient cognac house might not get the fanfare of some, but its cognacs are very special and a must for anyone who enjoys quality spirits. They are also compelling evidence of the need for that crucial element: time.

And if this doesn’t make you want to reach for a bottle and a great cigar, I have no idea what will.

For more information, please visit www.delamain-cognac.com.

You may also enjoy:

Hine Antique XO Cognac: Not Compulsory To Enjoy With A Good Cigar . . . But Highly Recommended

Hennessy Paradis Imperial Cognac: Ethereal, With Great Length And Complexity, Yet Balanced

Penfolds Special Bottlings: Spirited Wines, Distilled Single Batch Brandy, And A Fortified

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!