by Ken Gargett

A group of wine-loving friends of mine meet every month or so for a good lunch and to enjoy some fine wines. There is usually a theme, and wines are normally served blind to prevent the inevitable preconceptions.

This time, the order was to bring wines we each thought were worthy of Grand cru status or its equivalent. Some were stars acknowledged by all, while other wines engendered more debate.

A magnum of Pol Roger Sir Winston Churchill 1982 was lauded by all as an exemplary example of a stunning champagne. Grand cru worthy, indeed.

Rousseau, Rayas, Lafite, and Sassicaia all passed without too much debate. A Trimbach Clos St. Hune met more resistance, but only from heathens who do not appreciate great Riesling.

On the other hand, as fine as it was, a local Chardonnay from the Geelong region was considered perhaps Premier cru status, but we could not agree on elevating it to Grand.

All good fun.

Equipo Navazos La Bota de Manzanilla Pasada No 80, Bota Punta

One of the wines I brought along was a sherry, the Equipo Navazos La Bota de Manzanilla Pasada No 80, Bota Punta. Some among you will have no doubt that such a wine demands Grand cru status, while others will be horrified at the thought. And so it was on the day.

Sherry, a divisive wine?

Sherry is perhaps the most divisive of all wines, a real love-it-or-hate-it drink. I am in the “love-it” camp. I would also suggest that as well as the most divisive, sherry is the most versatile of all wines, ranging from the most bone dry, refreshing style to dense, treacle-like sweet wines that are beyond hedonistic.

We looked at the efforts of Equipo Navazos with one of its very rare spirits not so long ago – see La Bota 65 Ron ‘Bota NO’ – but it is, of course, sherry for which the firm has established an international reputation at the very highest level, not rum. A thrilling producer.

Now I fully understand if half the potential readers have already switched off and gone elsewhere. For some sherry will never appeal, and fair enough. Others know how good it can be. If you are not sure, please, give it a try.

How sherry is made

First, it helps enormously to learn a little. Not all sherries are equal, and the exciting and innovative bottlings we are now seeing from Jerez are as far from the dusty bottle of sherry your great aunt kept in the medicine cabinet as is possible.

The name “sherry” is basically the English version of “Jerez,” the main town in what is known as the sherry triangle in southwest Spain. The region has changed hands numerous times – Huns, Moors, Brits, Romans, and Ottomans have all left their mark in various ways, through occupation or otherwise.

El Corregidor vineyard, Spain

The relevant towns are Jerez, Sanlucar, and Cadiz, and the vineyards surrounding them provide the grapes – Palomino (by far the most important variety), Pedro Ximénez, and Muscat of Alexandria – for the various styles.

Pressing grapes for sherry

But first, there will be years of barrel maturation (large, old barrels usually called butts) in a solera system, followed by fortification with neutral grape spirit to between 15 and 20 percent. Each “set” of barrels in the solera is called a “criadera.” A criadera may have a handful of barrels or it could extend to thousands.

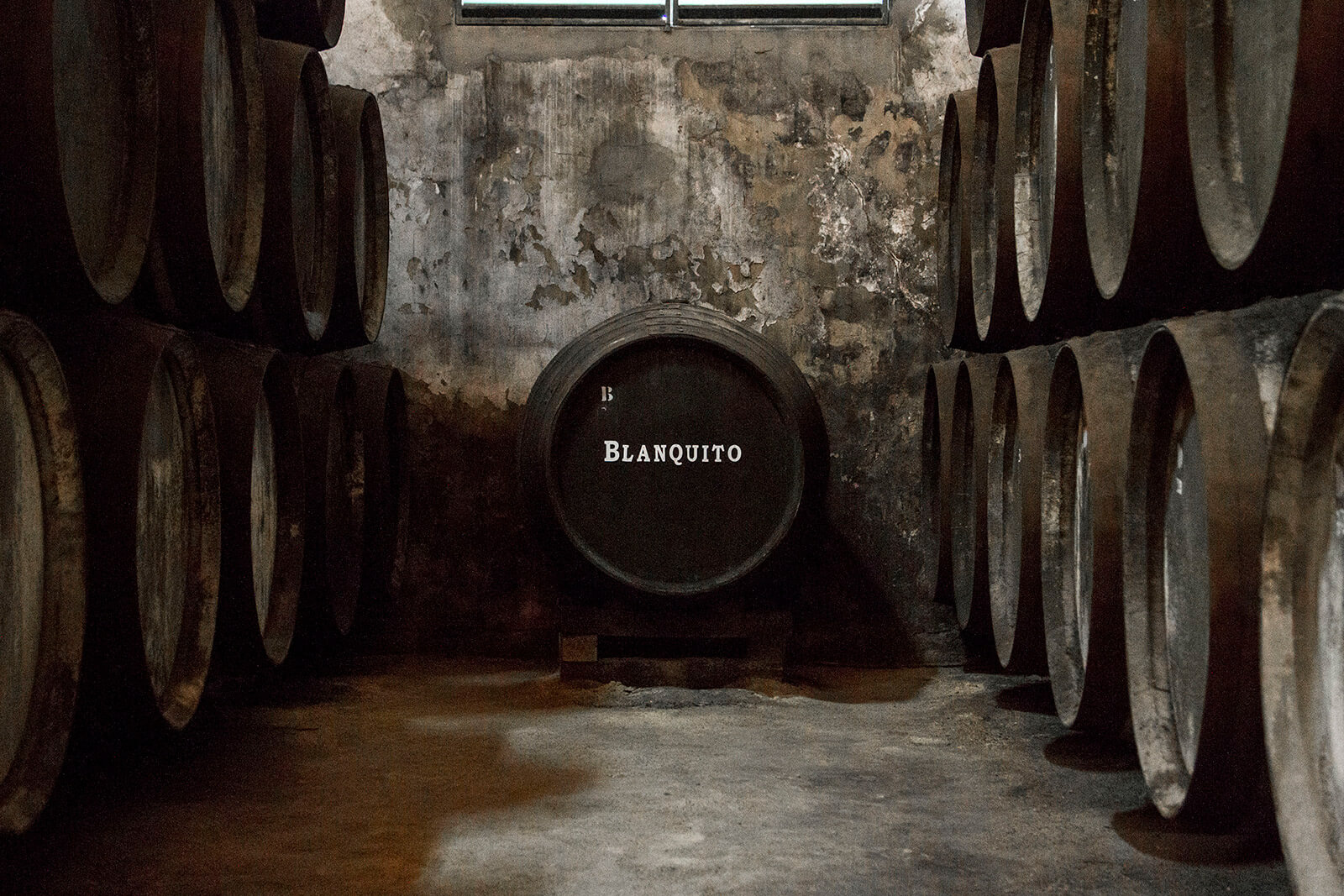

Barrels of sherry in a solera

When it comes time for bottling, the sherry will be drawn from the oldest barrels. This will then be replaced by material from the next oldest barrels. They in turn receive a top-up from the next oldest and so on, back to the youngest, which will then be topped up by new material. And so it goes, each year.

A basic solera has three to five criaderas, while a more complex one could have three times that. The youngest level is refilled every new harvest, keeping freshness, while the age of the older barrels ensures complexity.

The barrels are only filled to around five-sixths full. This is crucial, giving the sherry its character. The flor yeast, which grows across the surface of the liquid, feeds on oxygen to provide the fino/manzanilla styles.

The richer and more complex styles develop from oxidation. Where there is still significant flor, this can be minimal. But as the yeast dies, it imparts flavors such as a trademark nutty touch. Once the flor has fully died, the oxidation can really make its mark.

To digress, most serious kitchens will have a few bottles of sherry vinegar. These vinegars come from the barrels where the flor yeast did not succeed, and vinegar yeast won the day.

Of course, all winemakers enjoy a little innovation and experimentation. So occasionally one comes across a vintage sherry, a butt not used in a solera, but these are the exception.

As mentioned, Palomino is the crucial grape variety – the others tend to step in for the richer and/or sweeter styles. Palomino is considered an excellent grape to reflect its site, even though outside the region we so rarely hear of the terroir of the chalky vineyards. And it has excellent acidity, which is important.

Sherry ranges from parched bone-dry to unbelievably rich and sweet, with everything in between.

Gutiérrez Colosía fino sherry

The ubiquitous “fino” is the typical dry sherry. The deniers will tell you that you should avoid fortified drinks because they are too alcoholic. Fino sits at 15 to 16 percent, barely a whisker above many full-flavored wines. Look at chardonnays coming from Napa, shiraz from the Barossa, so many examples; 14.5 to 15.5 percent is far from uncommon.

The level of alcohol in fino is not a valid argument against enjoying it. Typical finos exhibit chalky and nutty notes, a seductive texture, and they can be surprisingly elegant, clean, and refreshing.

The situation of the barrels (butts) in the bodegas, and the bodegas themselves, are considered to play a major role. The prime example is the town of Sanlucar, on the Atlantic, where proximity to the sea is considered to impart a brine/seabreeze/oystershell/saline note to the fino from there.

Callejuela Manzanilla sherry

It is known as manzanilla, and a chilled glass on a warm day is close to vinous heaven. It can be bottled at an even lower level of alcohol but should be consumed soon after opening.

Helpful sherry terms

Before we go further, a couple of terms can be useful. Pasada is basically a manzanilla that is more mature and complex than the standards, providing a result not dissimilar to an amontillado. It will have been aged for longer and there is likely to have been a high number of criaderas involved.

Puntas are the barrels on the bottom rows at either end. They are often filled to higher levels and separated from other butts for use as a discrete bottling. The higher levels mean lower concentrations of flor, but the positioning of the butts means a higher humidity (and apparently can also mean a higher influence from dust mites, the acidity of which can impart a slight citric note – so they say).

Back in Jerez, the extra aging leads to amontillado as the flor dies. Fortification here is usually to 18 percent. Aging will be anywhere between six years up to two decades. Think extremely complex, warmer, and nuttier finos as the most simplistic explanation.

Then we move to oloroso, which basically starts life as a fino but the flor is killed to allow for what is known as an “oxidative regime.” These are the most complex, richly flavored, and deepest of all the sherries. Again nutty notes, but here the texture comes into its own. Many think that oloroso is sweet but that is not so. These can be, if sweetness is added by way of sweet base wines. But it is not automatic.

All of these styles have an array of different foods and cuisines with which they make brilliant matches. One example is sherry and Japanese food, fresh and versatile itself, which is amazing. But there are so many options.

For the luscious Pedro Ximénez, PX grapes are left to ripen into intense sugar bombs and then concentrated further by drying (raisining) on mats. After barrel maturation and fortification, these can be the most decadent of wines. Try them with ice cream or a chocolate dessert. Or just by themselves.

Needless to say, we are not finished: palo cortado is a bit of this, a bit of that, but not really fitting in. Accidents, delightful accidents for sure, throwing things into chaos. Basically, a fino butt fails (the flor just will not do its job) and the contents end up somewhere between amontillado and oloroso, with a little bit of both.

The latest craze is for en rama sherries, which are bottled directly from the barrel with almost no filtering.

We’ll leave muscatel (from the Muscat of Alexandria grape, with more acidity than PX but not quite as sweet) and cream sherries (a curious but once extremely popular blend of oloroso and Pedro Ximénez) for now.

Hopefully, this has made you at least a little curious and keen to try some.

A few names in the sherry world to know

I’ve mentioned Navazos, which is a superstar, but production is very limited and can be expensive. Lustau is in the same vicinity.

There are many examples representing more accessible pricing.

Delgado Zuleta’s La Goya Manzanilla is a must, named after a singer/dancer, not the artist.

A solera of sherry at Gutiérrez Colosía

A small but very old family business, Gutiérrez Colosía, based in the town of El Puerto de Santa Maria, makes excellent sherries across the range (I’ll confess to a glass of its excellent nutty amontillado providing necessary support as I sit here typing away).

Sanchéz Romate from Jerez is a class act and a nice mix of the old and new. Barbadillo is another favorite.

Valdespino and La Guita, which are both part of the Grupo Estévez empire, also offer extraordinary sherries. González Byass’ Tio Pepe and others in the range, not least an occasional but rare vintage sherry. There are many more.

This is, obviously, a mere scratching of the surface into the world of sherry, and you can be sure that I’ll be visiting it again.

Speaking of visiting, Spain is a bucket list destination for many of us, and to be honest there have been a number of times when I have abandoned plans for other European countries, such are the charms of this brilliant country.

No one needs my exhortation to spend time in such fabulous cities as Barcelona or Madrid (and plenty more), but it always amazes me how few make it down to Jerez and Sanlucar.

They are thrilling cities to visit, though they can get a bit warm in summer. Visiting the bodegas, the tapas bars (a friend recently told me he’d found the best tapas bar in the world when last in Spain – I asked if he meant Casa Balbino on the Square at Sanlucar and, sure enough, that was exactly where he meant), local restaurants and vineyards. Magic.

Casa Balbino tapas bar

If, however, you are not heading any further south than Madrid then there is a bar you must visit. My favorite in all the world. Just off Santa Ana Square, La Venencia. A hole-in-the-wall that serves nothing but five different sherries, all from barrel (plus some great tapas). An old Hemingway haunt with no photos allowed – anathema to the Instagram generation of course. I love it.

More on sherry soon.

You may also enjoy:

Alta Pavina Citius Pinot Noir: A Spanish Wine Revelation

Wild Turkey Master’s Keep: A Great Bourbon For Drinking Now

Michter’s Kentucky Bourbon (Plus The Difference Between Whiskey, Whisky, And Bourbon)

Sullivans Cove Makes The Self-Professed World’s Best Single-Malt Whisky, But Does It Measure Up?

Buffalo Trace Antique Collection Bourbon: Cult Treasure

Yamazaki 12-Year-Old Japanese Whisky: Why Pricing Has Gone Through The Roof

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

A timely article! For too long has sherry been consigned to the category of “what my spinster aunt used to drink”!

One minor quibble: most people take their wines with food, and so are keen to know how to pair a sherry. FWIW, I would suggest amontillado with seafood (lobster!), and I once had the heavenly marriage of Pedro Ximenex with a Welsh rarebit (thanks, Gordon Ramsay!). Sherry is definitely not for drinking on its own, IMHO…

Thanks Alex. Agreed. And its versatility makes it ideal as hard to think of much you could not find a sherry to match. Japanese food works especially well. But all that said, if someone is offering me a glass of PX at the end of a meal, or a refreshing fino on a warm afternoon, I’m certainly not saying no.

A whole article on Sherry and not one Frasier reference??

i feel deeply ashamed. i am a big fan, seen every episode, i think. a horrifying oversight.