Tracing The History Of My Grandfather’s Pocket Watch And Delving Into English Watchmaking

Last year my mother showed me a silver pocket watch. All she could tell me about it was that it had belonged to my late grandfather. This is the story of my quest to identify it and its original owner.

The author’s grandfather’s silver pocket watch (photo courtesy Colin Alexander Smith)

I remember asking my grandmother, many years ago, “What did Grandpa do?”

His occupation would remain a mystery for us as the answer was invariably, “Well, he was a wireless operator during the war.” I could only conclude that in post-war Britain, having been “a wireless operator during the war” entitled one not only to a “demob suit” but also a lavish pension and a lifetime of ease, as another 22 years had elapsed between the end of World War II and Grandpa’s statutory retirement date, during which time he allegedly did nothing.

Or perhaps that “wireless operator” was a euphemism for an operative of a more clandestine nature whose activities carried on long after the war and into the cold war period, rather like the central character in Michael Ondaatje’s Warlight.

Some years later my cousin, who had been told the same story, revealed that her mother had sat her and her sister down one day and said, “I have something to tell you, girls . . . your grandfather . . . was a taxi driver!” My cousins turned to their mother and replied, “So what?”

My grandmother’s and aunt’s socially aspirational reticence was misplaced. If they had dug deeper into our family history, as my brother has done recently, they would have learnt that my grandfather had simply carried on a long family tradition going back four generations to the mid-1800s. His forebears had started and owned one of London’s largest horse-drawn cab companies, based and residing in what soon became some of the most sought-after streets in Chelsea, eventually selling up their stock of some 70 horses and carriages in 1911 as motor vehicles gradually took over.

London cabmen from ‘Street Life in London,’ 1877, by John Thomson (photo Wikimedia Commons)

My great-great-great-grandfather Joseph Smith is listed in the 1851, and subsequent, London censuses as a “cab builder and owner” (the term “cab” is derived from the French “cabriolet”); 1851 was a pivotal year for the London cab industry as the Great Exhibition drew more than four million visitors to the capital (equivalent to one-third of the population of the British Isles) and, as a result, the city’s cab drivers earned substantially larger than usual sums over the six-month period.

Some cab drivers subsequently became owner-employers with a fleet of carriages and horses, employing not only drivers but also mechanics, blacksmiths, and stable hands. Joseph Smith was one such employer.

By 1867 the business had prospered to the extent that Mr. Smith held a “bean feast” for 40 employees and guests in Thames Ditton, which was reported in the West Middlesex advertiser 1867 as “an example worthy of imitation” and at which a toast was drunk to Mr. Smith, during which it was observed that “ . . . the grand secret of his success was punctuality in all business matters and perseverance.”

Now, if Joseph Smith had a reputation for punctuality, he must have had a reliable timepiece to refer to day and night.

Could that watch be the timepiece I had before me now?

Was this Joseph Smith’s silver pocket watch? (photo Colin Alexander Smith)

To my surprise, when I wound it up the watch ran for a few days. I have since had it professionally serviced (at a cost somewhat exceeding the value of the watch) and it now runs perfectly, albeit with the regulator at the “slow” extreme of the setting range.

The dial reads “THE VERACITY WATCH – J.N. MASTERS, RYE – ENGLISH MAKE.” J. N. Masters, the son of a watchmaker, had run a workshop and shop in Rye from 1869 onward selling English watches, but latterly importing and casing up Swiss movements.

This dates the watch (or, at the very least, the dial) to pre-1896, the year in which J.N. Masters was incorporated as a limited company as indicated by later “Veracity” dials being marked “J. N. Masters Ltd, Rye.”

The low serial number when compared to similar Veracity models of which I have seen photographs, the indication “English make,” and the fact that it is an English lever escapement initially suggest that it dates from the 1890s.

Having an heirloom of this age and quality is always a thrill, but this particular watch has piqued my interest as my knowledge of English watches has hitherto been limited to what I have read about in books like Dava Sobel’s Longitude and what I have read about and seen of George Daniels and Roger Smith’s watches on the internet.

It seems to me that like French watches (which I know a little bit about) and German watches (which I don’t), English watches have a character of their own that is quite distinct from the Swiss watches and movements with which most of us are more familiar.

English music

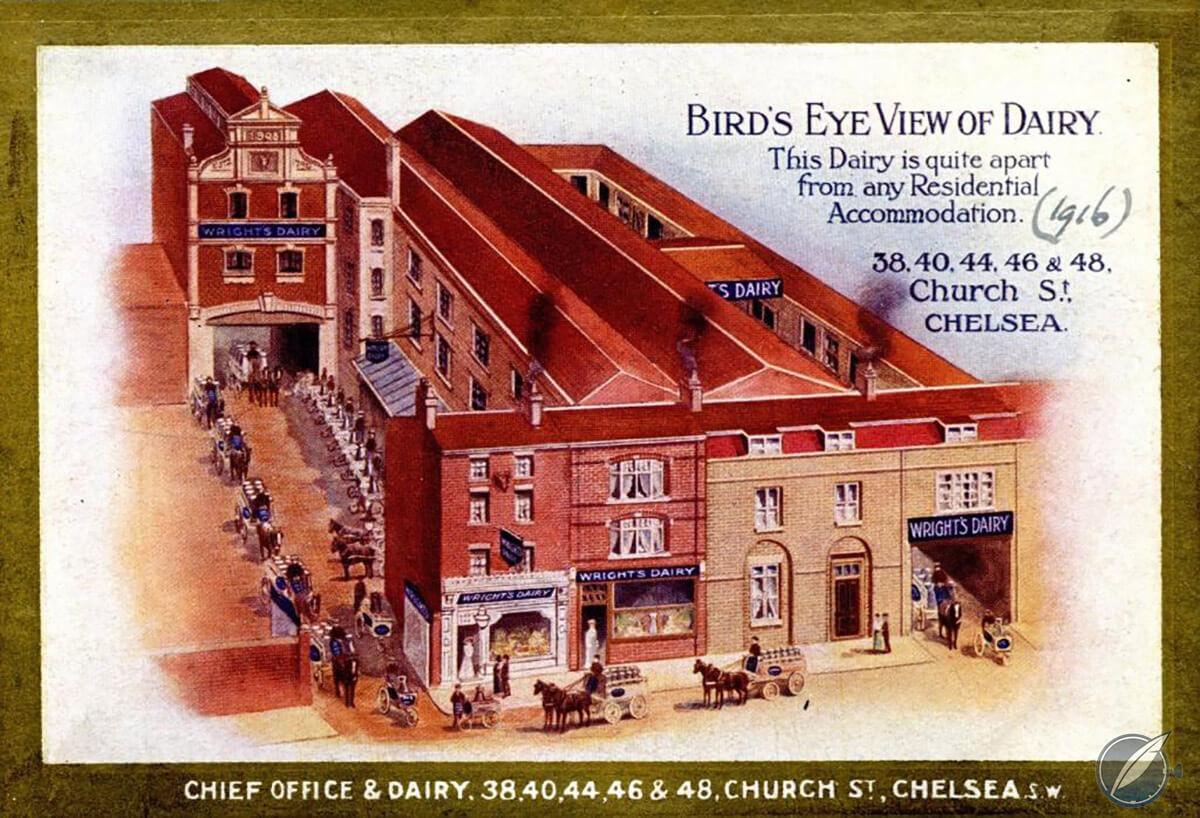

Going back to my grandmother and aunt for a moment, one thing I had heard them mention on numerous occasions was that my grandfather’s Aunt Florence had married the boy next door in Chelsea, one William H. Wright, owner of Wright’s Dairy on Old Church Street. The former storefront of the dairy and the building subsequently erected in the courtyard behind it are of interest to London historians because of the porcelain pastoral scenes and the life-size cows’ heads set into the walls, which can still be seen today.

Wright’s Dairy (photo courtesy rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com)

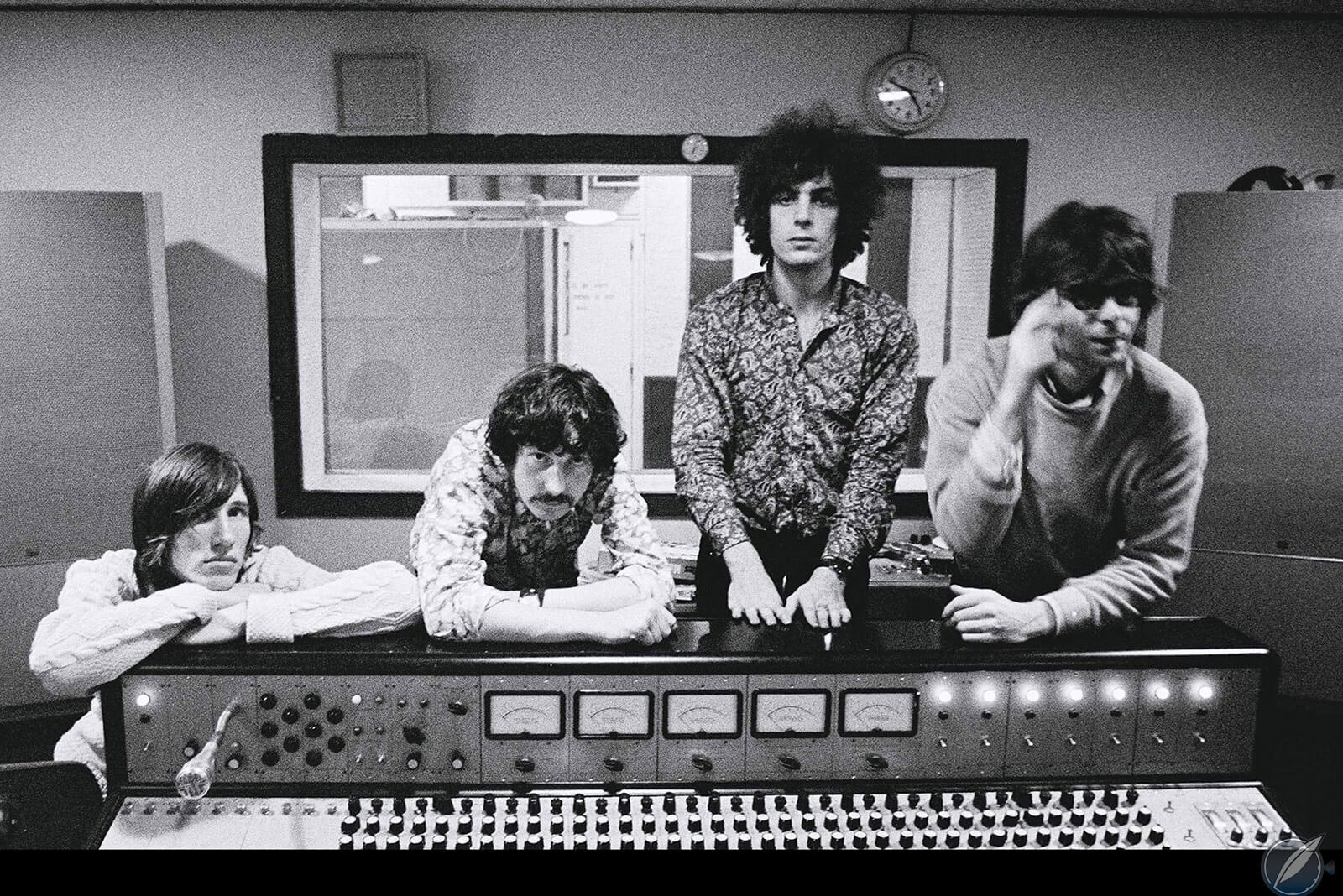

But the former dairy (now an airy, loft-style townhouse with exposed ceiling beams) is of far greater interest to music fans: in the 1960s it was converted into a recording studio, Sound Techniques, where some of rock’s seminal albums where recorded. GQ Magazine described it thus in April this year:

“Set up in 1964 by a sound engineer and a vision mixer as a handcrafted redoubt from the ‘big rooms’ ruled over by the major labels and their minions, during its brief, ten-year run, Sound Techniques was where Pink Floyd recorded their first single (thereby introducing the straight world to London’s most out-there ensemble). It’s also where The Incredible String Band, Fairground Convention, Jethro Tull, John Martyn, Sandy Denny, and Steeleye Span laid down most of their best-known work. And it’s where Nick Drake – surely the most enigmatic and certainly the most impactful proponent of the period’s deep dive into a sort of needle-cord pastoralism – recorded all three of his albums . . . anyone in search of the ‘ground zero’ of the UK’s late 1960s/early 1970s musical search for an ‘English Arcadia’ – best summed up by the era’s penchant for peacockery and patchouli, matched by an increasingly abstract expression of these islands’ folk roots – will be familiar with its output.”

Pink Floyd in the recording studio (photo courtesy Andrew Whittuck)

But this Englishness is a slippery concept. Just when you think you’ve pinned it down, it morphs into something else just beyond your field of vision.

This is highlighted by the UK’s decision to leave the European Union, driven largely by the older, provincial English population (the Scots wanting none of it, by a large majority) who when pressed for an explanation resort to platitudes about cricket, beer, and pounds shillings and pence, harking back to an “Empire” that was all but long gone by 1970.

Peter Ackroyd’s novel English Music (1992) also comes to mind, in which he weaves literary and artistic references into a Dickensian tale in an attempt to define English culture through its art and literature, (the “music” of the title). Can we define English watchmaking in a similar, not purely technical manner?

The first thing that struck me was the sheer heft of this watch (although this is probably true of older pocket watches in general when compared to twentieth-century models); this thing has a real presence just sitting there on the desk.

Not only does the case stand reassuringly tall, but the slightly domed glass stands proud of the case by nearly 2 mm. The hours are indicated on the very traditional enamel pocket watch dial by the customary elongated, sharply printed Roman numerals, and the hands are of blued steel. One has no doubt that a stout Victorian gentleman would have been proud to carry it with him all day.

The author’s grandfather’s silver pocket watch (photo courtesy Colin Alexander Smith)

Opening up the case back, we find a large, weighted balance wheel swinging almost languidly over the escape wheel and the pallet lever poking out at 90 degrees, which adds an additional point of visual interest as it flickers back and forth, unlike the straight-line arrangement of a Swiss movement, in which the pallet lever is barely visible. The hairspring flexes back and forth, a shimmering deep blue.

The author’s grandfather’s silver pocket watch with open case back (photo courtesy Colin Alexander Smith)

But then there is the austerity of the single, frosted gold-colored brass plate covering all of the rest of the movement, held in place by large blued steel screws and unadorned other than by a serial number. No individual, curving, bridges for each component of the movement train here as we might expect to see in a Swiss watch.

Seen in the right light, the contrast between the relatively bright blue screws and hairspring and the frosted brass plate is rather striking and has something contemporary about it.

I find this aesthetic with its plain, functional shapes is today echoed in the much more recent watches made entirely by hand by George Daniels and Roger Smith, such as the Anniversary Edition.

Movement of the George Daniels Co-Axial Anniversary Edition By Roger Smith

But the Daniels method of working is not representative of traditional English watchmaking, which in reality it was a cooperative venture between makers of movements, cases, dials, and hands, much as it was in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Switzerland and France.

At that time, there was a considerable flow of knowledge between the three countries, partly for social and political reasons, as exemplified by the peregrinations of Abraham-Louis Breguet between Paris, England, and Switzerland and, with leading English watchmaker John Arnold, the mutual apprenticing of their respective sons.

In a more recent example, when Hans Wilsdorf founded Wilsdorf & Davis in London in 1905, subsequently the Rolex Watch Company, he sourced movements and cases from both English and Swiss manufacturers, only later settling on a Swiss supplier for its ébauches and eventually relocating to Switzerland primarily for reasons relating to British customs duties.

So what happened to English watchmaking?

In 1838 a steamer called the Pulaski sank off the coast of North Carolina with considerable loss of life. It was only in 2018 that a U.S. salvage company identified the wreck as the Pulaski and managed to salvage certain items, including four pocket watches by H & J Daniels of Liverpool, Thomas Helby & Co., Arnold Adams & Co., and S.I. Tobias & Co. – all English.

This indicates that at the time, American passengers wealthy enough to be traveling in this manner, and to own a watch, unanimously preferred English-made watches.

It was not until after the 1850s and 1860s that U.S. watch companies such as Elgin and Waltham began to assert themselves, undercutting the English industry by using modern manufacturing techniques and mass production, however the process of decline had begun much earlier.

In part, the reasons for the decline of English watchmaking included a combination of commercial and technical factors as exemplified by this description of an escapement problem in Watchmaking in England, 1760-1820 by Leonard Weiss.

“The horizontal escapement was invented in England . . . English engineers had by experiment proved that friction was much less between different metals than between similar, therefore the watchmaker made the horizontal wheel of brass and his cylinder of steel. Meanwhile public taste demanded flat watches, and the Swiss made the horizontal escapement of steel entirely, thereby sacrificing theory to demand. After a time it was found that, whereas the brass wheel destroyed the cylinder very quickly, the steel wheel hardly marked it in years of wear, clearly showing that even if there be a slight excess of that friction that retards motion, it is a less evil than the absolute wear of the machine itself. The Swiss were thus rewarded for studying the taste of the public by a large trade, and have made their country the home of the horizontal escapement.”

To shed further light on the matter, I sought help from Dr. Rebecca Struthers, who is not only one of a handful of women operating in the upper echelons of international horology, but also a qualified gemologist and historian and the first person ever to be awarded a PhD in horology.

She now operates out of a historic building in Birmingham’s jewelry quarter, together with her master watchmaker husband Craig, as C&R Struthers Watchmakers. Together they are fast becoming the quintessential English rock star couple of the horological world – I wouldn’t be surprised if they listen to P.J. Harvey’s Let England Shake when they are working at their workbenches.

Dr. Rebecca Struthers and Craig Struthers (photo courtesy Mark Salmon)

Dr. Struthers’s PhD thesis “Fakes, Forgeries and the Birth of Mass Production in the European Watch Industry” (which she presented to the Horological Society of New York in July 2018) was based on her forensic examination of some 30 eighteenth-century watches at the British Museum, ostensibly signed “London” but with various makers’ names that turned out to be fictitious, which she refers to as “Dutch forgeries.”

“Whilst cataloging some antique watches I came across one made in around 1760 that, despite being signed as London-made, looked completely unlike the London watches I was familiar with. When I looked up the name of the maker, ‘John Wilter,’ the reference book simply listed him as ‘perhaps a fictitious name.’ I did a bit more research and it soon transpired that this was pretty much all we knew about the most prolific type of watch forgery in the eighteenth century,” Struthers told Elizabeth Doerr in 2017.

“The emergence of these ‘knock-off’ London watches, together with economic pressures, spelled disaster for the genuine London industry that fell into a state of depression from which it would never recover. Back in the 1700s it was England, particularly London, that was home to the world’s most famous watchmakers, and watches made in the city commanded a premium. By the mid-1700s we started to see watches appearing of a much lower quality than the fine London work, in a style different to that of the English watchmakers, and signed with spurious names for which there is usually no trace they existed as real people; let alone watchmakers.”

In an investigation worthy of Hercule Poirot, involving French military shipyards and Dutch timber merchants, Dr. Struthers traced the manufacturing of these “London” watches back to a string of towns on the Franco-Swiss border (which subsequently became the cradle of the Swiss watch industry we know it today) and their distribution by Dutch merchants travelling across Europe.

Eventually London, which had been to eighteenth-century watchmaking what Bordeaux and Burgundy are to red wine, was cut out of the equation completely.

As an academic, Dr. Struthers demonstrates that English watchmaking was undercut and ultimately destroyed by cheaper, lower quality, but quite legal at the time mass-produced copies and that this situation was an inevitable step in the evolution of the global watchmaking industry.

As a watchmaker, she now draws on her research, “to pick up where the English industry left off, but giving it the benefit of over a century of German and Swiss improvements, but still in something very traditionally made in an eighteenth-century cottage industry style with 1940s-1970s machines and hand tools.”

Dr. Rebecca and Craig Struthers have thus embarked on what they call Project 248, an almost entirely in-house movement hand-made using original lathes (which they have baptized “Maus,” “Helga,” and “Heidi”) featuring an upgraded English lever escapement, English rocking bar keyless work, parachute shock setting, a slow 2.25 Hz/16,200 vph beat, and gold jewel chatons secured by screws.

The movement was reverse engineered from a caliber made in Coventry, England in the 1880s and will be decorated by a local master engraver. The presentation box will be sourced from further afield in Scotland.

The first run of five watches is currently in production, and if supporting independent watchmakers forms part of your collecting strategy you can sign up to be notified of availability (be prepared for a long wait).

C&R Struthers Project 248

Regarding the dating of my watch and identifying its first owner, Dr. Struthers tells me that the traditional style of English watch case and movement decoration in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was extremely decorative, featuring “fine acanthus scroll engraving, frosting, and yellow gilding.”

But by the late nineteenth century, the watches that were still being made in England were of a more pared-down design, sometimes influenced by Swiss and American designs, albeit still with a restrained elegance.

There is a reason for this: from the mid-nineteenth century onward, English watchmakers, including the substantial cottage industry supplying parts to movement makers, suffered terrible hardship, not only from the Franco-Swiss produced “Dutch forgeries” described above, but also from the rise of the American watchmakers Waltham (1850) and Elgin (1863, after poaching seven of Waltham’s watchmakers), who introduced the mechanical production of standardized parts, thereby significantly (and honestly) undercutting English prices without compromising quality.

After having been pointed in the direction of the hallmarks on my watch’s silver case, I have now ascertained that it was of fine-quality silver (lion passant – that’s the one walking along, as opposed to the upright lion rampant) and hallmarked by the Chester Assays (three helmets and a sword) in 1897 (0).

More helpfully, it is signed TPH – Thomas Peter Hewitt – the inventor of the keyless works and founding partner of the Lancashire Watch Co., in Prescot, near Liverpool.

So J.N. Masters in Rye must have ordered the silver case and – presumably – the movement from the Lancashire Watch Co., casing it up with his own dial in his workshop. So it is more probable that the watch originally belonged to Joseph Smith’s son Arthur, who inherited the family business – and perhaps his father’s rigorous punctuality.

The Lancashire Watch Co. was established in 1890 with the specific aim of federating the numerous watch part makers in the area (Prescot had long been a key watchmaking center in England) and taking on the Americans at their own, production-line-based game. It produced more than a million watches over its lifetime, but the enterprise’s business model, while a logical step and perhaps comparable to British Leyland trying to adopt Japanese lean manufacturing practices in the 1980s, struggled financially. The company folded after 20 years.

The Lancashire Watch Co. was dissolved in January 1911 with a nine-day auction of its assets – the same year that my great-grandfather sold his hansom cabs and horses at auction in London.

It was the end of an era for all concerned.

You may also enjoy:

Meet The Struthers: English Watchmaking The Old-Fashioned Way . . . Sort Of

Roger Smith Series 4 Triple Calendar: Excellence In Hand-Crafted English Watchmaking

Behind The Lens: Roger Smith Series 2

Why Great Britain Is Actually GREAT Britain: The R.W. Smith GREAT Britain Watch

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Dear Colin Alexander Smith, dear Q & P Team,

you made my day. Danke vielmals. Your latest article is such a fine way of story-telling about the history (of watchmaking), some word-origins, and the passion of watch-rescueing. Initially I clicked for the watch but again remained for the story. After reading the article I can feel a strong appeal to look up all boxes, drawers, and boxes to find our grandparents pocket watches and listen to ‘their’ stories. What a lovely time pass (not only in corona-times) this could be.

p.s: The movement design and construction is timelessly exquisite and obviously an inspiration for (some), (so many) modern pieces. By the way: Might there be a future for the sadly missed and vanished pocket watches (e.g. Voutilainen TP1, Struthers The Carter)? A rare find. Or is it ‘the end of an era’?

Kinds regards Thomas

Hello Thomas, glad you enjoyed it and that you have been inspired to go looking for treasures!

As far as pocket watches are concerned, we take our phones out of our pockets to check the time, so maybe we can be convinced to carry a pocket watch in the other pocket!

Colin

That was a great read.

So as far as I can tell, the only English (true) watchmakers who today stand atop the ashes are Smith and Frodsham (Garrick being reliant on Andreas Strehler’s expertise – although that may have changed). Hadn’t paid much attention to Struthers, but they very much seem the real deal.

Over the years of viewing beautiful swiss-style movements, I now get much more of a thrill from seeing the old English style of architecture and finishing.

Do you know if there are any other brands (of any nationality) making movements like this? Or is it vintage or bust (or sell a kidney)?

Thanks Gav – if you can pick up a copy of issue 93 of QP Magazine there is an article on one David Cottrell who is making watches using the Daniels method, and having his work (dis)approved by Roger Smith much as G Daniels did for Roger Smith! No movement photos, sadly. There is also a young Australian lad who has adopted the Daniels method.

If admiring English watch movement architecture without breaking the bank is your thing, the going rate on eBay for a non-working 18th C English fusée movement is about £20. Spend a bit more and there are some complicated marvels available.

Colin

That’s great, thank you. Hadn’t heard of David Cottrell – just had a drool at his instagram pics thenoo.

*edit* Just did a wee search, and Stefan Kudoke’s Kaliber 1 has a great approximation of what delights me about this almost-lost style. And his watches are an absolute bargain.

It’s now on my radar.

That’s a good find, Gav, and at a compelling price for a hand made movement!

The Kudoke 2 is VERY high on my want list.

Hello:

I very much enjoyed reading your research into your family watch. We’re lucky in the USA in that we can use the serial number on an American movement to give an estimated production year, or even for some makers the exact date on which the movement went to the finishing shop. (See pocketwatchdatabase.com).

For English watches, I have always been told that a major reason for their decline was the continued use of a fusee to try and equalize the force on the gear train, due to the mainspring not providing constant force when fully wound versus rundown. However (so I’ve been told), spring steel for the mainspringg became much more reliable and constant, and a fusee was no longer required, yet use continued in the U.K. for decades to cone.

Hi Scotty, glad you enjoyed it and yes, I think there were a variety of essentially technical reasons that contributed to the decline. The serial number on this watch is in the 150,000 range, whereas I have seen photos of Masters Ltd watches from 1911 with the number in the 800,000 and 1,000,000 range, so I guess this is an earlier one as regards being made by Lancashire Watch Co.

Hello, I don’t know if you are aware of it, but your watch is clearly made by the Lancashire Watch Company of Prescot,

near Liverpool in the 1890’s.

I can get more details if you wish.

Regards, Mike Smith MBHI. (London).

Hi Mike,

Thank you for reading the article. The last five paragraphs are about Lancashire Watch Co.

Colin