I have attended the odd auction. I have even gone to auctions with the intent to bid on a watch. But that hadn’t yet worked out for me.

What ended up working out for me, and leading to my first auction purchase, was putting in an absentee bid on a long shot. I had little hope.

Rewind to last summer. Attempting to work on a story that was giving me a brief spot of trouble, I turned to Facebook (as one does) to take my mind off it for a few moments by scrolling through what my friends were up to that day.

My private Facebook feed generally has two main topics: lots and lots of watches, and people photographing their food. I usually ignore the latter (unless it’s my food, of course) and interestedly look at what’s on whose wrist that my friends are chatting about.

It was then that I spied it: someone had posted a link to an auction set to take place in two days, the topic of which I was quite alarmed to see. Parisian auction house Artcurial was auctioning off what was left of Alain Silberstein’s inventory.

Spoiler alert: I am now going to sway in a spot of nostalgia and adoration while summing up the essence of Alain Silberstein.

Alain Silberstein: watch designer and enfant terrible

“Le vrai bonheur est d’avoir sa passion pour métier.” (“True happiness is to have one’s passion as a profession.”)

The Silberstein brand’s tagline was one that could describe a number of people in the Swiss watch industry, for watches often seem to be the passion of the people found working here, be they spring polishers, salesmen, or even journalists.

But to jump industries from interior architecture to watchmaking – without being a watchmaker, I might add – at a time when mechanical watches weren’t even close to the trendy fashion items they have now become . . . that’s passion.

I met Silberstein early in my career in the watch world, a few years after he had founded his eponymous company in 1987.

I sat down with him every year at the Basel Fair and other exhibitions, and even visited him in his chosen place of residence, Besançon, France. Silberstein, who moved to this city noteworthy in horological history from Paris, loved to reminisce about the past. It seemed that the more he talked about the difficulties of his beginnings in watches, the more it seemed to confirm to him how wonderful the present and the future were.

It was a long and sometimes rocky road for him.

Beginning his career in the watch industry at a time when few were buying mechanical watches, Silberstein still felt this was just the right place for him, despite the fact that he was not a trained watchmaker, but an interior architect. It was the design aspect of watches that attracted him, a big inspiration for him being the advent of Swatch.

Doing what no one else had done before suddenly didn’t seem so far away.

In the year 1987 there were few visionary watch enthusiast entrepreneurs ready to stake their livelihoods on a profession that was seen by many as having no future. But look at those who also jumped in with two feet early on – men like Gerd-Rüdiger Lang of Chronoswiss, Jean-Claude Biver of Blancpain (and later Hublot), and Rolf Schnyder of Ulysse Nardin.

History has proven them right. Not only were they successful at what they created during this time of quartz uncertainty, they are now looked up to by the rest of the industry for their pioneering work and untiring spirits. They simply did what they believed in.

Alain Silberstein’s style is unmistakable in this Marine 20 Krono, introduced in 2007 in celebration of 20 years of the company

Alain Silberstein was part of this early group, but his claim to fame was to be a pioneer in color, if you will. While the rest of the high-end watch industry was focusing on exhibition case backs, the seriousness of mechanical movements, and how to convince the consumer to want to wind watches (batteries seemed so much easier), Silberstein was more concerned about how to take the seriousness out of luxury watchmaking and make it more playful.

A hard road; and to top it off, for a man managing a watch brand, he was handicapped by being French (not Swiss), located in the picturesque Jura city Besançon just on the other side of the border from Switzerland where the French is spoken a tad differently, where the francs then in use were French (not Swiss).

Color, color, and more color

Silberstein’s watches were a colorful world full of geometric joy. His early designs involved strong primary colors and easily recognizable geometric shapes in surprising places like the crown and pushers. At that time there was little thought put into special movements: the earliest watches of the so-called mechanical renaissance were nearly all powered by ETA automatics.

Silberstein was always the first to tell you that he was not a watchmaker, but a designer. The watch had to be high-quality and of a lasting nature, therefore it was important to him to mainly use mechanical movements.

As time went on, the industry changed and Silberstein went through phases of highs and lows like any good artist or creator. Enjoying his role as the watch world’s enfant terrible immensely, Silberstein began to experiment with textures and colors that few, or even none, had used before.

He was definitively among the first to set diamonds into stainless steel – until that point it was unheard of to combine the ultimate item of luxury with something as “mundane” as steel. But this was Silberstein, through and through.

The Alain Silberstein Krono Bauhaus 2 Alligator Tricolor of 2006; note the case covered with yellow alligator leather

The mid- to late-1990s brought about more color and texture in the shape of leather, rubber, and fur, not only for the watch’s strap, but as a covering for the case and in some instances even the dial.

What some people shook their heads at, others loved like nothing else. His designs polarized – and still do to this day.

By the turn of the millennium, Silberstein was the first to go outside the industry in search of new ways to get color onto a mechanism’s components. He found just what he was looking for from a small French supplier from another industry, and could now make his base plates lilac-hued, bronze, blue, red . . . you name it. Whatever he was working on, there was now a color for him to change the look of any part.

Right around this time – and in tune with the rest of the watch world – he began to get more interested in the exclusivity of his mechanisms as well. The mechanical renaissance was in full swing, and collectors were now looking for the most exclusive technology money could buy along with original design.

One no longer precluded the other.

Taking this as his cue, Silberstein then came up with his most head-shaking idea yet: a limited edition of sixteen different tourbillons, each one funkier than the next, and powered by the now-defunct Progress tourbillon caliber.

This surely must be one of the world’s wildest tourbillons: the Alain Silberstein Tourbillon Papaya of 2006

“Kinetic art” is what he called this marriage of color and technology, and it was very successful for him. Remember that at that time tourbillons were still serious business; clothed in anything other than a traditional look they were bound to generate comment and criticism.

Returning to color, Silberstein and his outside-the-box-thinking suppliers found a way to enamel steel and titanium cases in a lasting manner without it chipping. So Silberstein decided to make a line of tourbillons and chronographs in various colors of camouflage design.

The following year it was dots in the same technique. There seemed no end to Silberstein’s love affair with color. Until his company hit the magical twenty-year mark in 2007.

“These are like colors for me,” Silberstein explained to me at Baselworld 2007 as he showed me timepieces housed in brushed titanium cases with a ruthenium-plated finish outfitted with TechnoTime movements. Progress had become STT, which was subsequently purchased by Bovet in 2006, so the original tourbillon movements he used were longer available to purchase.

“My search for colors has now led me to a place that is more related to materials.” Silberstein said, showing me the Marine Krono 20, which I would describe as something approaching a re-issue of one of his first watch lines.

“This watch is a monster,” he explains, “but like a pebble, too. I’m trying to go back to my roots, which is the shape, the form. Something neat, simple. I’m performing the elusive search for the pure line. The simpler it is, the better for the customer. I’m not telling some sort of brand story or imposing a story that is not the honest me. A watch is like a white piece of paper; an abstract work of art that raises an emotion.”

To me, Silberstein’s timepieces always looked like complete works of art, not to be judged either on the basis of their movements or their appearances alone, but as a whole object.

“The movement is important for high watchmaking,” Silberstein always underscored. “But it is a mistake to identify a watch only by that criterion.”

The modern era

Silberstein dropped out of sight around 2010 after having collaborated with Max Büsser to design the first MB&F performance art piece, which came out in 2009 in a limited edition of eight pieces. Called the HM2.2 Black Box, it was a minimalist rendition of MB&F’s HM 2 in a solid black, Bauhaus-style case.

To me, it was both very unlike Silberstein while being very like him in a modern sort of way; his latest designs in 2009 and 2010 had been less colorful and more gunmetal in style.

The MB&F timepiece was too intense for me; I personally disliked that Silberstein’s signature color was missing from it in a more intense way. The jet black case, while beautifully designed, signified to me that perhaps something else was going on with him – like an artist going through a certain phase. And I can only guess that the worldwide crisis of 2008 may have negatively affected his business, just like many others.

Silberstein surfaced again at Baselworld 2015, though not with his own brand, but as the designer of Romain Jerome’s Subcraft case. The Subcraft is the latest edition of that brand’s Spacecraft (for more on that see A Brief History Of Transportation Ending With The Romain Jerome Spacecraft). Silberstein rounded out its angular lines, and its color is available in two finishes: natural titanium and black PVD-coated titanium.

The Silberstein-designed Romain Jerome Subcraft makes the subdued MB&F HM2.2 Black Box look like an explosion of rainbows

Again, though, no funky color.

The Artcurial auction

I miss Silberstein’s kinetic sculptures. I miss his color. I miss the craziness. I miss his designs. I was certainly one of his biggest fans.

So when the news of the Artcurial auction came up in my newsfeed, I was immediately interested, though sad at what I could only surmise was the reason for the auction: bankruptcy.

I was, however, also quite dismayed, because in the space of two days I could never arrange to go to Paris for the live auction or even register to bid live online.

My only remaining option was to fill out an absentee bid form and hope for the best. So, after poring over the catalog for hours, I managed to narrow my choices down and – fingers crossed – fill in my bid form.

After what seemed like days of waiting for the results, I was finally rewarded with the news that I had won one of the auction pieces. Oh, elation!

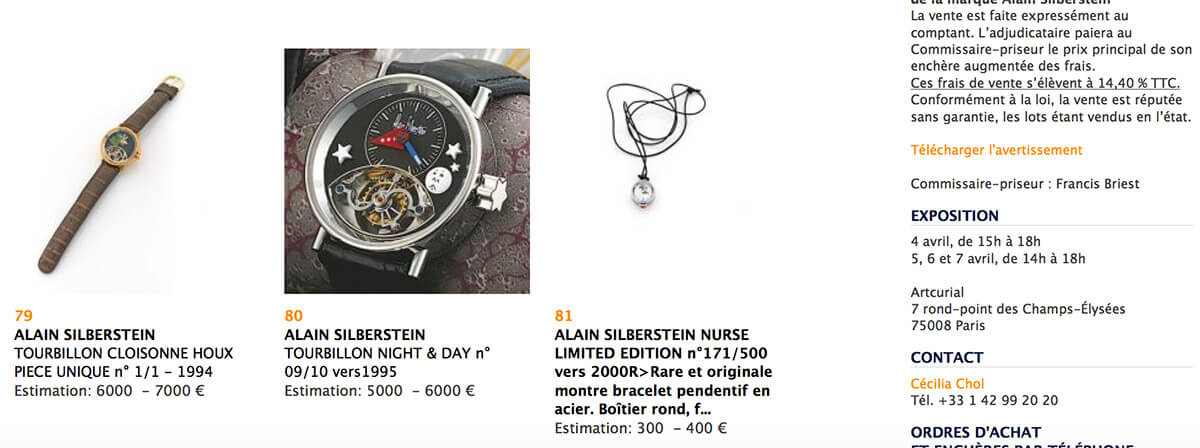

It turned out to be one of the funkier pieces Silberstein dreamed up for women, even though there was less room for color: a “nurse’s watch.” A nurse’s watch is usually hung around the neck like a necklace, but with the watch dial upside down, so all you have to do is lift it toward you slightly to read the time.

Naturally, the miniscule ticking pendant was styled with Silberstein’s signature color and geometric shapes (I had only bid on the colorful pieces), and it made me so happy to put it on and wear it with pride once it arrived.

So, once again Silberstein became a pioneer of sorts: he was responsible for my first auction purchase.

Quick Facts Nurse Limited Edition

Case: stainless steel, 22 mm

Movement: automatic ETA Caliber 2671

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds

Limitation: 500 pieces, made in the early 2000s

Original price as of 2004: €2,600

*This article was first published on July 25, 2015 at My First Auction Purchase: Alain Silberstein Pendant Watch.

You may also enjoy:

Shy No More: MB&F LM1 Silberstein

Watches And Art: At Baselworld 2017 With Artist Alexa Meade And Maurice Lacroix

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

LOVED the article.

I’ve been an AS fan since I first saw the full-page ads in the yearly issues of Watches International. I was able to buy a Krono II for myself in 1995. It’s the only AS watch I’ve ever owned, but I still keep up with e-bay auctions weekly, to see what weird models might come up for sale.

I missed the Artcurial auction, I didn’t hear about it till it was too late. Not sure if I would have won anything, but it would have been fun to bid on those!

I hope to own a Kotwaz clock one day.

Thanks for reading! Our friend Alain seems to have many admirers still, which goes to show that good design never dies!

i’ve had a number of AS watches..including 2 of his black gummy Krono B which I think remains his best design. One i lost, the other was stolen. I replaced with a Krono Titanium but not the same. and sadly – you cannot find the replacement rubber bracelet anywhere which is what gave the watch it’s beauty. A real shame.