The late George Daniels, CBE, has a lot to answer for.

It is because of his example that professional and amateur watchmakers from Australia to England (and no doubt others yet to be discovered in places in between) are willingly embarking on the daunting venture of making watches almost entirely by hand, right down to the screws.

Anyone who has even so much as stripped down and reassembled a watch will grasp the enormity of such a task. This horological foolhardiness has in some cases been provoked after a watchmaker gets his hands on a copy of Daniels’ book Watchmaking.

Others have tried, and some even succeeded, because they can.

The Struthers’ workshop is a veritable treasure chest filled with the old, ancient, and even older (photo courtesy Georgina Cook)

Craig and Dr. Rebecca Struthers, owner-founders of Struthers Watchmakers, operating since 2012 out of a historic building in the traditional jewelers’ district in Birmingham, England, thought that they could make a handmade watch movement and, even more impressively, have done just that.

Dr. Rebecca and Craig Struthers in their workshop

The Struthers are better qualified than most to undertake such a venture thanks to their training (both are experienced watchmakers), their experience in servicing, repairing, and restoring old (sometimes very old) English and Swiss watches, and creating new watches fitted with refurbished and refinished vintage movements. They use traditional watchmakers’ lathes and milling equipment to make any plates, bridges, and wheels that a movement restoration might require.

This restoration work, combined with Rebecca’s historical research (she has the world’s first PhD in horology), has inspired them to go all the way and make their own watch movements too.

Project 248 is the working title that refers to the 2 minds, 4 hands, and 8 mm watchmaker’s lathe they will use to make the first run of five watches.

The Struthers Project 248 book

According to their website, “For their first in-house movement, the Struthers will be developing a new improved English lever escapement, picking up where the British industry left off in the late nineteenth century. Whilst the Swiss have dominated watchmaking for nearly 140 years, the English lever escapement has been largely ignored; the Struthers will revive this traditional escapement using the latest advancements in materials and technology.”

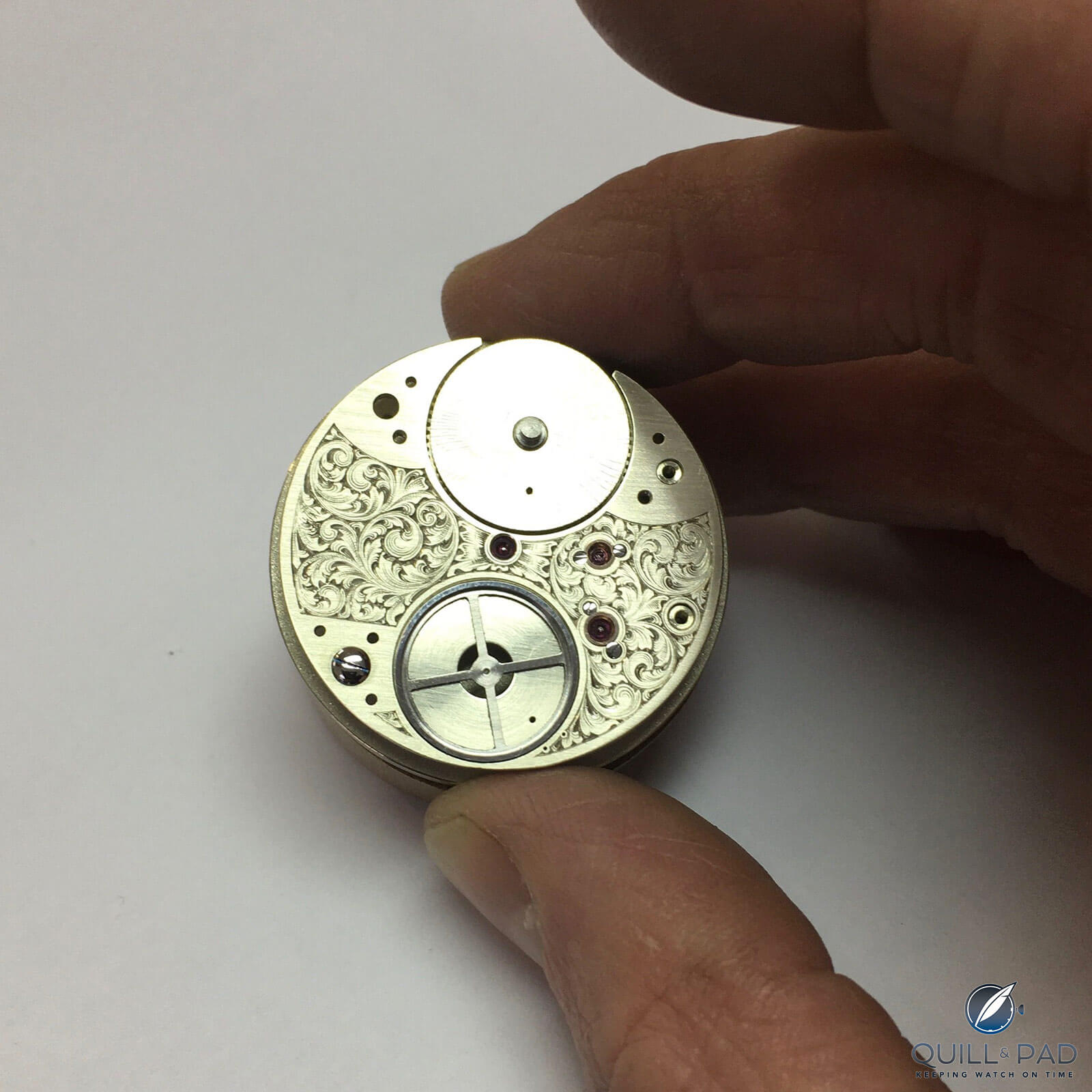

With a top plate design inspired by an 1880s English pocket watch, the German silver movement features an English rocking bar keyless work, parachute shock setting, traditional slow-beating 2.25 Hz (16,200 vph) balance, and screw-mounted gold jewel chatons.

From the outset, the Struthers recognized that as they will not be altering their working methods in terms of manpower and machinery used, they will be limited to producing just two watches per year.

To complicate matters, they have of course been working from home for the last two months and their raw materials suppliers have been out of action, so progress has been limited to working on movement parts.

Husband-and-wife team Craig Struthers and Rebecca Struthers work side-by-side day and night (photo courtesy Georgina Cook)

I caught up with Craig and Rebecca Struthers in June 2020 to find out how things had been going under lockdown and what they had been able to achieve under these challenging circumstances. And I quizzed Rebecca on her view of current and future English watchmaking and where she thinks Struthers fits in.

Where do the Struthers fit in?

The Struthers’ approach to making their own movement draws heavily on their previous activities of restoring and refinishing watches from a broad historical period, with inspiration from over 500 years of clock and watchmaking. I asked what sets traditional English watchmaking apart from Swiss and French watchmaking of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

According to Rebecca, “English watchmaking at its peak during the seventeenth to late nineteenth centuries was set apart by being some of the finest quality work in the world. It was also far more traditionally handmade than its foreign competitors, which contributed greatly to the downfall of our industry. The USA and Switzerland both embraced standardized mechanical production decades before the UK. By the time the UK finally looked to the US to improve their production capacity in the 1880s, it was already too late.”

A historical English movement awaiting refurbishment at the Struthers workshop (photo courtesy Georgina Cook)

Like many watch aficionados who have begun to take an interest in English watchmaking, I have been learning to detect and have rather fallen under the charm of the English style of watch movement, which is quite distinct from what eventually became the standard Swiss and U.S. movement architecture (as typified by an 1880s “anonymous” key-wound Swiss pocket watch with individual curved bridges for each wheel or a 1910 Omega pocket watch with its two curved top plates). I asked Rebecca what she considered epitomized the English style.

“The classic style of English watchmaking in its golden age was still very much associated with British craft. In addition to its exceptional finishing, fine acanthus scroll engraving, frosting and yellow gilding on movements are all very traditionally English,” she answered.

Current media attention on “English watchmaking” tends to focus quite understandably on the “one pair of hands/one watch” method laid down by the late George Daniels and perpetuated by solo watchmakers such as David J. Cottrell.

But the Struthers are at pains to point out that this is not by any means the traditional English watchmaking method, which was very much a cooperative venture between a combination of cottage industry specialists and larger parts, movement, and case makers.

A good example of this was the re-creation of John Harrison’s H4 started in 1997 by English watchmaker Derek Pratt with case construction, dial painting, and movement engraving outsourced to specialists (the dial is Dutch, but not a “Dutch forgery”), with the project eventually completed in 2014 by Charles Frodsham & Co.

How the Struthers see the future of English watchmaking

“There are very few British watchmakers left, and we’re all very different. I would like to see more solidarity in the UK craft as a whole but that’s down to the individual makers,” Rebecca answered.

“I think, or at least I hope, that prospective customers value integrity and transparency. I like to believe they would at least be equally passionate about investing in something where they can see their money has been used to employ the skills of multiple little independent heritage craftspeople as they would be about commissioning something that will be made by one person.”

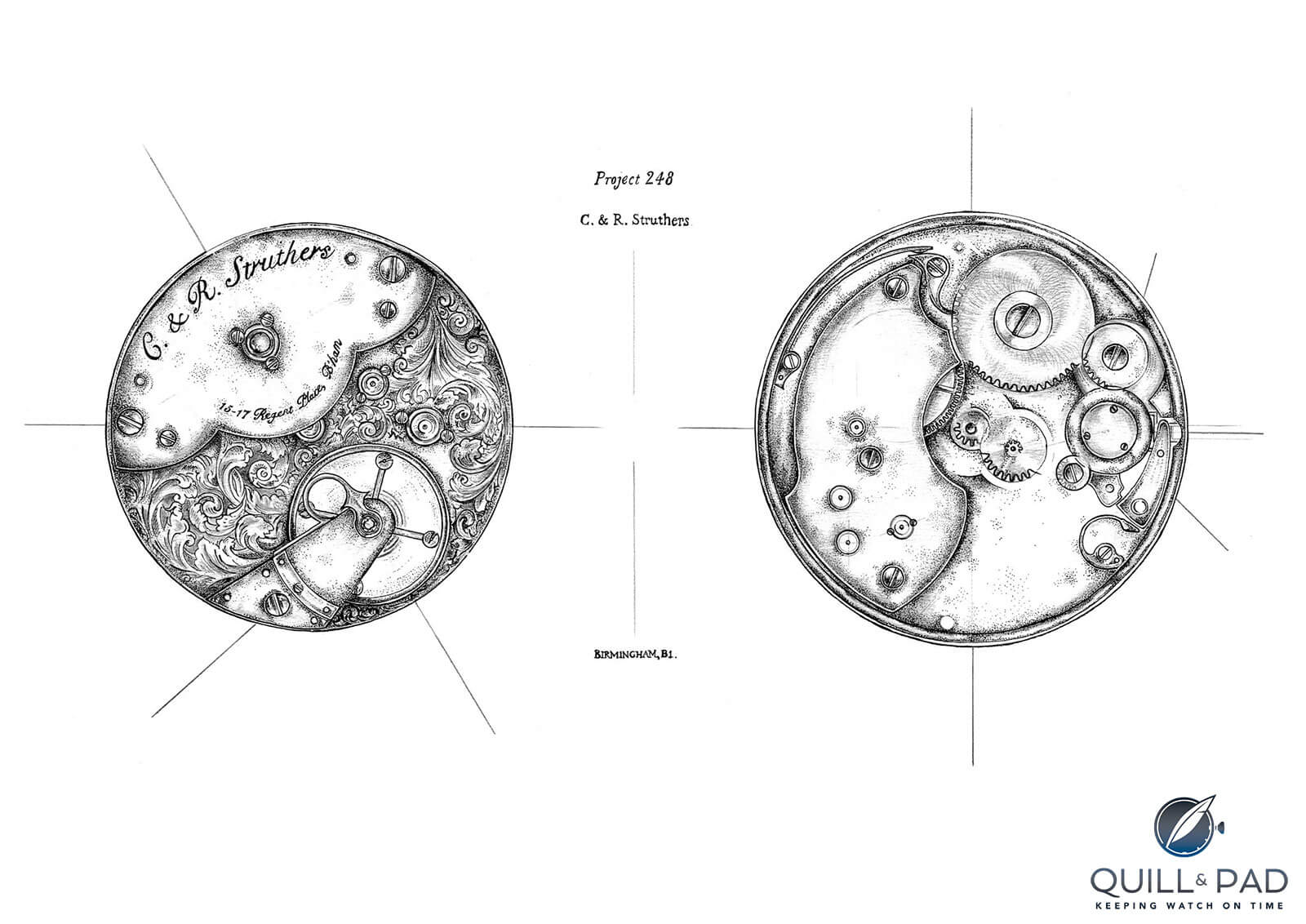

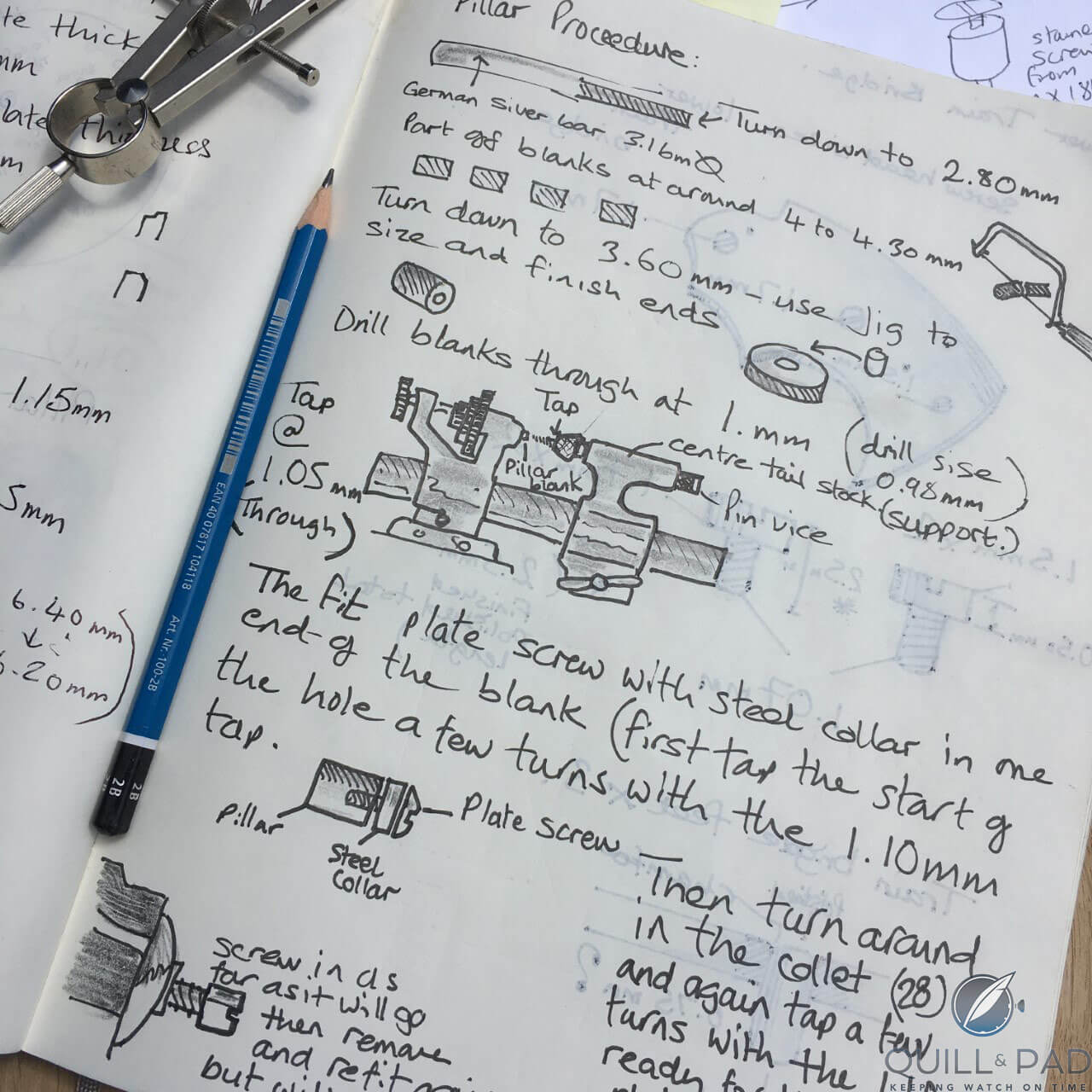

Struthers Project 248 movement sketches

Given that watch snobs currently turn up their nose at a watch simply as soon as they learn that it runs on an ETA movement, which, setting commercial politics apart for a second, demonstrates considerable ignorance about the excellence of ETA movements, some of the stellar watches they are used in and the Swiss producer’s historical evolution, I asked whether cooperative working between individuals and firms (as opposed to “everything must be made in-house and/or by one person”) could become “cool” again in the watch industry.

“I don’t think it ever stopped being cool, I just think watchmaking has become lost in business and disconnected from its roots,” she level-headedly answers.

“But then, I’m a maker and always have been; I love working with amazingly talented and inspiring artisans. I get so excited seeing their work, visiting their workshops, and sharing ideas. We’re watchmakers, we make cases and movements, so bringing engravers, enamelers, and goldsmiths into a project brings a whole new dimension and skill base.

“To me, cool exists in a pub over a pint of beer discussing how to create something that hasn’t been done in over 100 years with a bunch of insanely talented artisans from other trades.”

You can’t get more English than that . . .

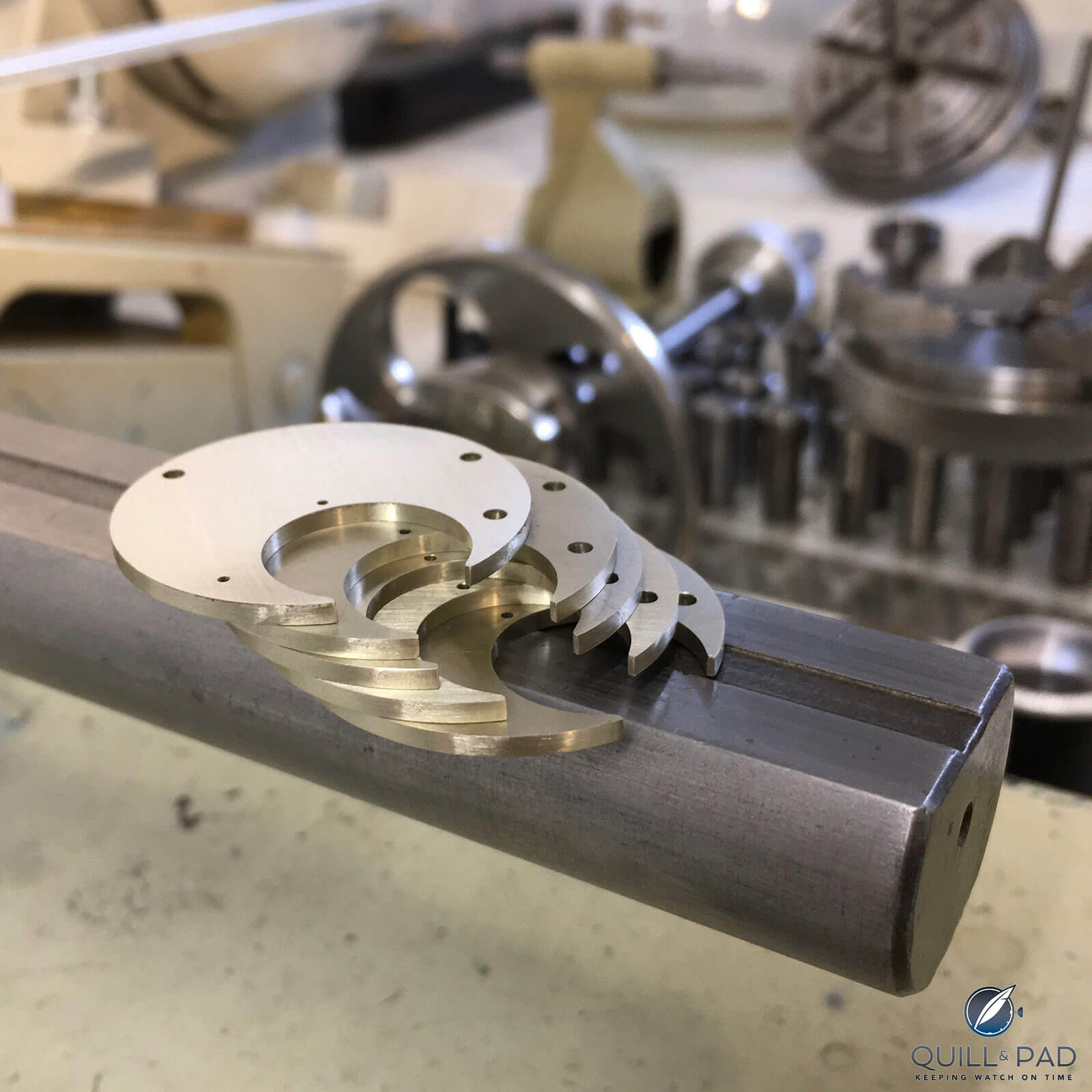

Mainspring barrels in progress

Project 248 under COVID-19 lockdown

According to Rebecca, “We’ve been very fortunate in being enable to continue working on Project 248 from home during lockdown. Although the space is tiny in comparison to our Birmingham workshops, it does have the bare essentials to carry on manufacturing most of the parts needed to create our first five ébauches.”

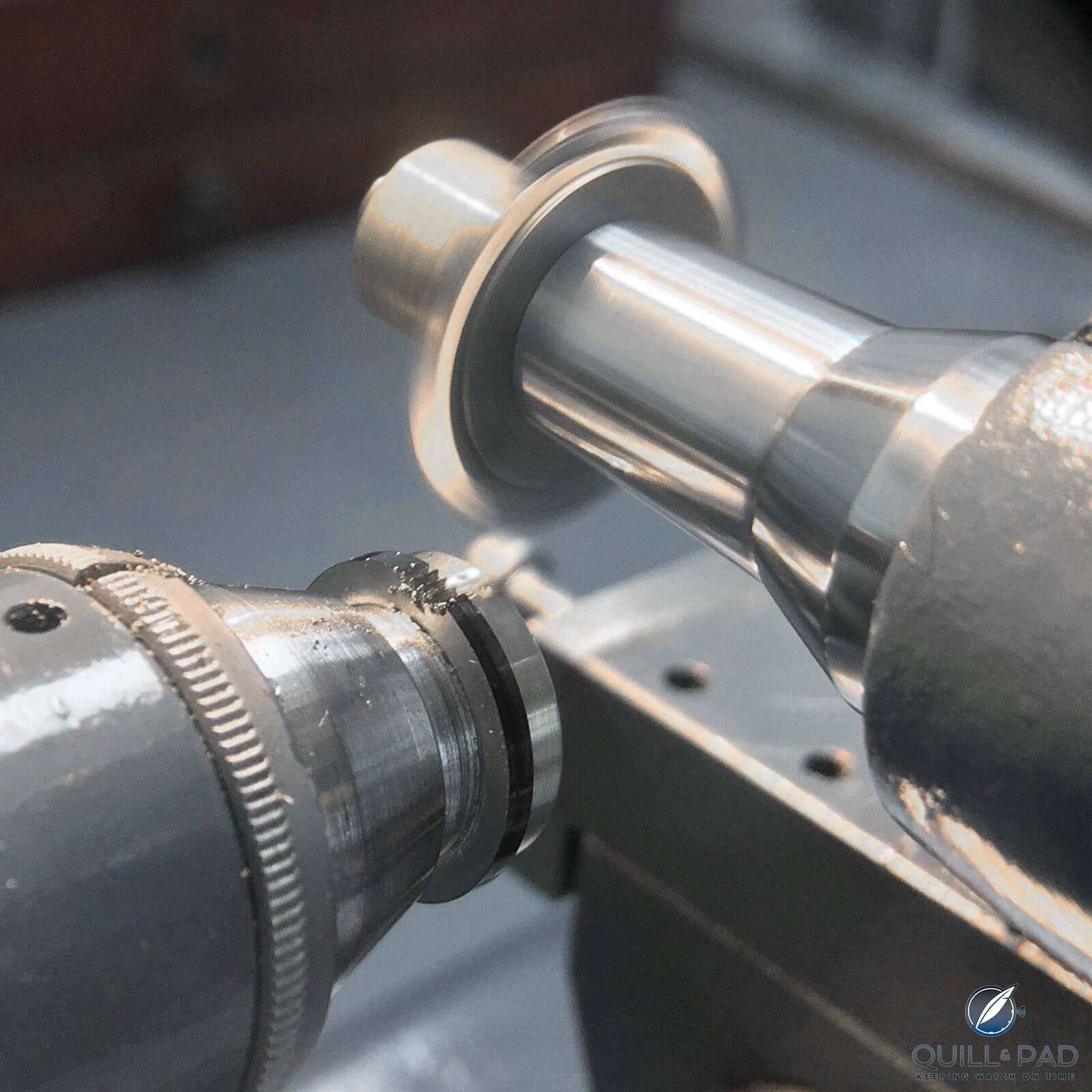

Turning the seating shoulder on a watch plate pillar

I was a little disappointed to learn that the Struthers do not live over the shop in the traditional English craftsman’s manner (as did John Harrison if I remember correctly), so there has been no question of them popping downstairs for a screwdriver during lockdown.

“Our home is in the Staffordshire Moorlands, in an eighteenth-century former weavers’ cottage, so in many ways we’re quite literally re-creating English watchmaking as a cottage industry! It certainly seems fitting for the house to be involved in British manufacture again.”

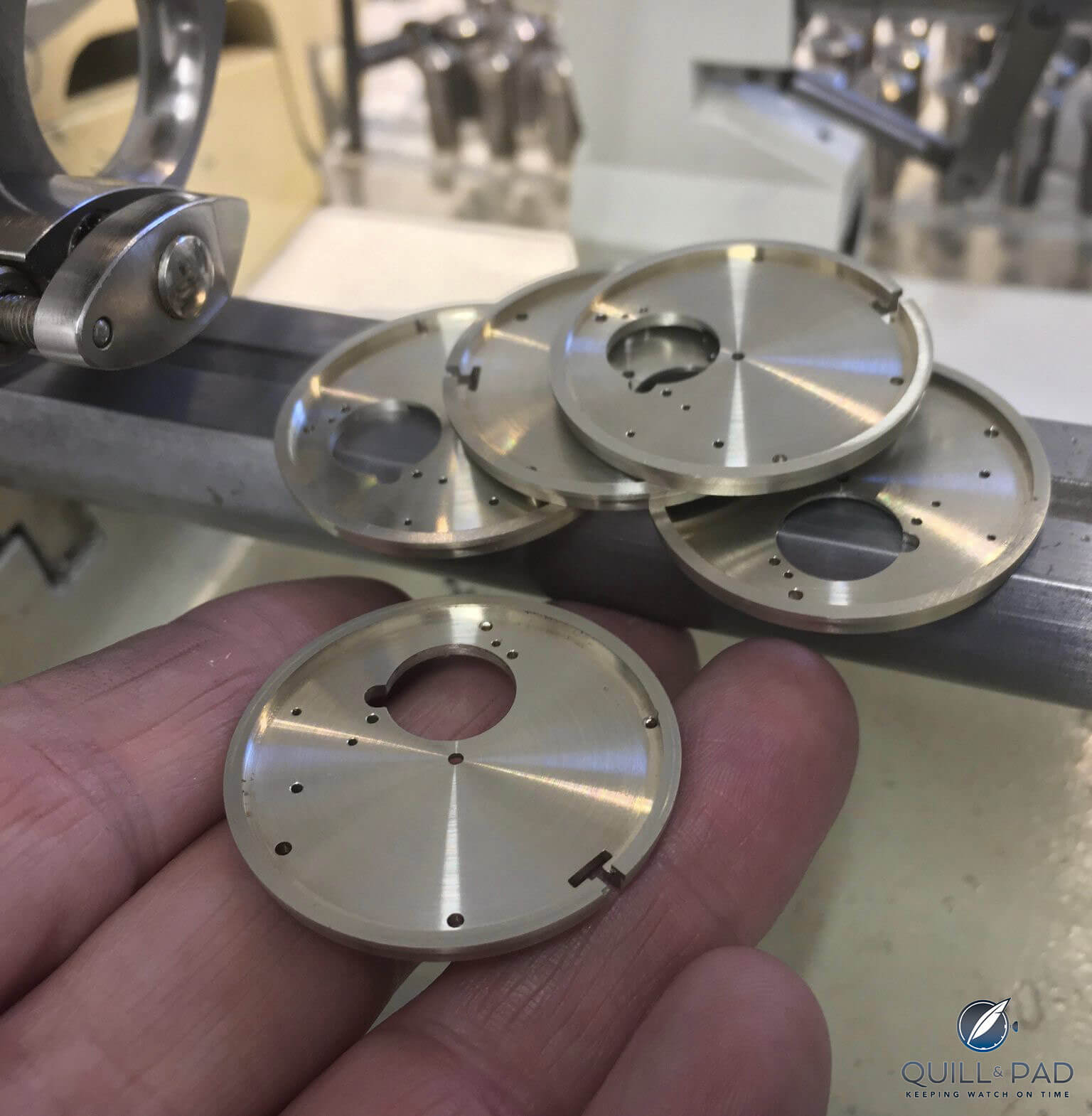

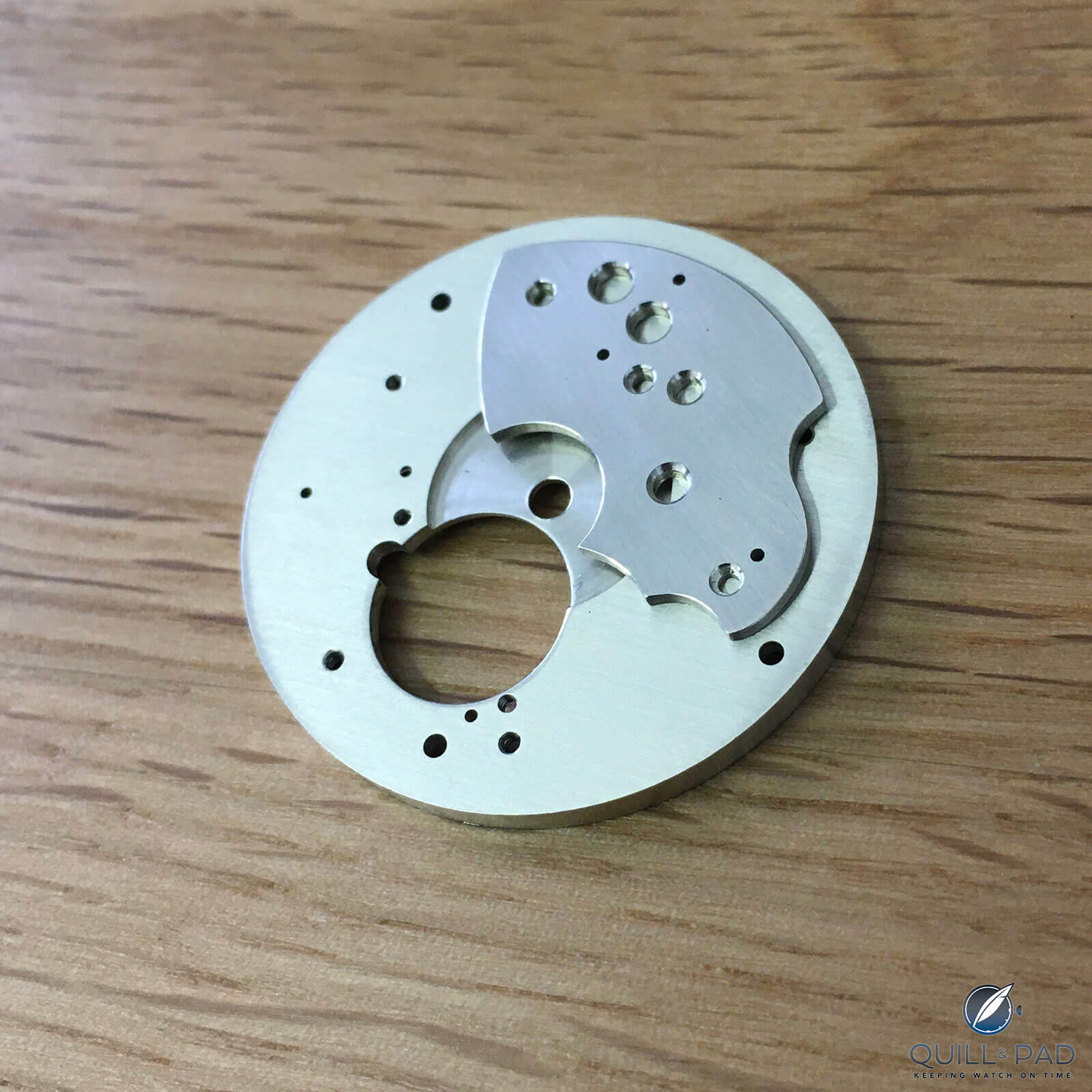

Base plates blanked out in the rough using an 8 mm lathe, micro milling machine, and pillar drill

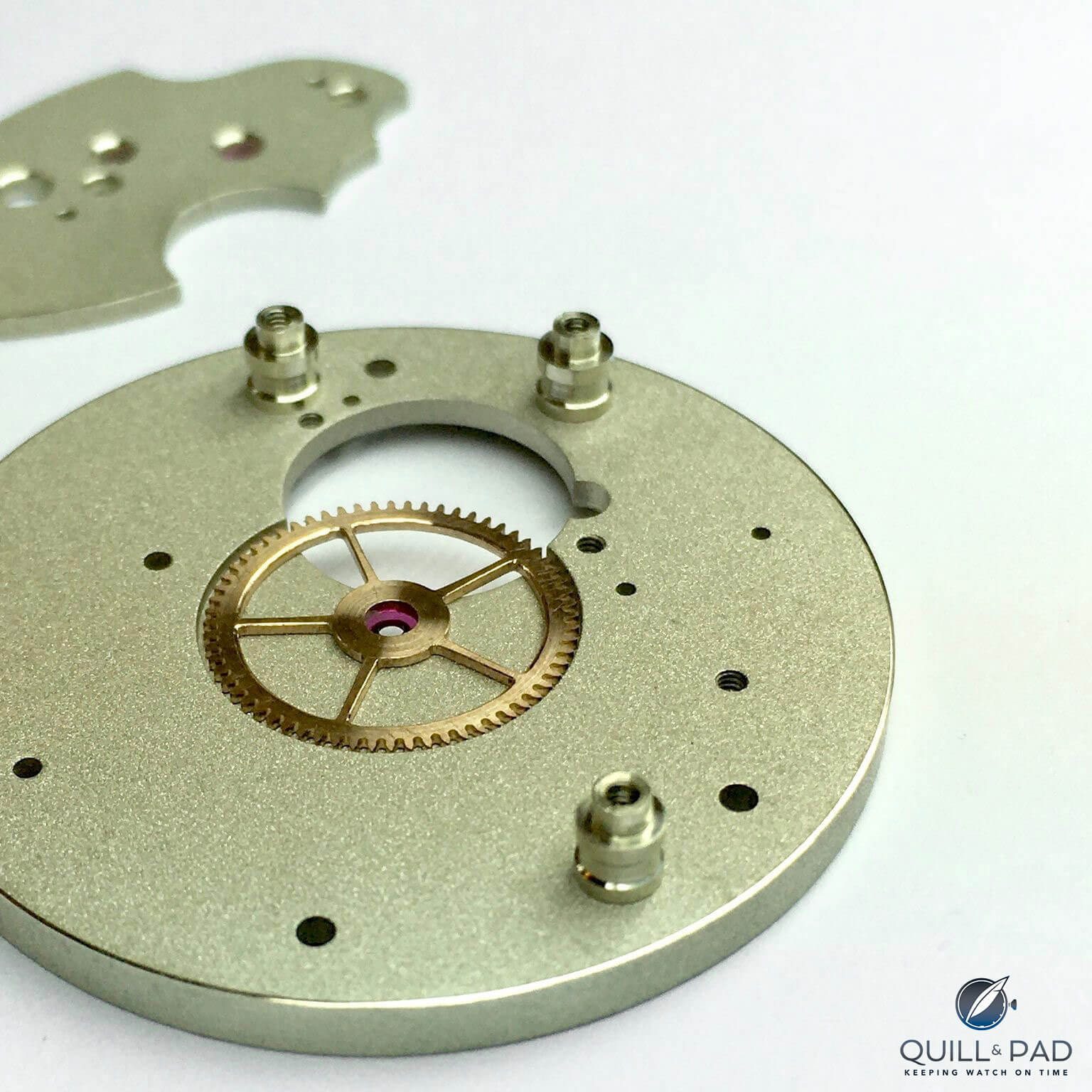

The Struthers’ Project 248 movement features a German silver base plate with frosted finish and polished beveled edges, which on its own looks like an expensive piece of contemporary jewelry. When combined with the complexity and delicacy of the movement mechanism itself, the idea that such an exquisitely crafted object has been entirely made by hand rather than spat out by a computer-controlled machine goes some way to explain the fascination of handmade watches.

Center wheel and base plate

“At home we have an 8 mm lathe, a pillar drill, a micro milling machine, and a selection of hand tools. It’s amazing how resourceful you can be when you have to,” Rebecca notes.

Top plate blanks turned, ready for facing off

The Struthers Project 248 watch

The initial production run of five watches has already been reserved by buyers as far afield as Indonesia, but you can register your interest for future production on the Struthers website.

Lower train bridge blank ready for milling, finishing, and jeweling

Rebecca went on to explain that while the majority of the base components have already been made, there is still work to do finishing parts, and that as a result of lockdown forcing their suppliers to cut back or stop production completely, they have been set back on collaborative operations such as enameling and engraving.

Project 248 ébauche with watch plate engraving by Florian Güllert

The Project 248 dials will, as with previous models, be blanks made by Struthers and enameled “downstairs” by their landlord, Deakin & Francis, a boutique jewelry and enamel manufacturer whose origins date back to 1786, operating from the premises directly below the Struthers workshop (but temporarily suspended due to the COVID-19 lockdown).

Early dial prototypes in vitreous enamel

Another striking aspect of the Struthers approach is that both the technical and aesthetic aspects of their watch designs are set out beforehand with considerable skill by Craig Struthers, with nothing more than pencil and paper.

How to make your own watch at home

Knowing that the person who hand-drafted the original designs was also directly involved in the making of the parts and resulting movement adds an additional layer of interest for customers. Not to mention the fact that the Struthers can provide clients with relevant sketches and drawings along with their watches.

Rebecca concludes with the observation that, “The initial idea for the project started back in early 2016, so it’s really exciting seeing it finally come together.”

Cutting the gear teeth for the mainspring barrel on an adapted 8 mm lathe

As passionately traditional watchmakers, the Struthers are committed to not upgrading their equipment, not boosting production, and not hiring dozens of staff. So in that sense they are not aspiring to initiate or represent a renaissance of English watchmaking on an industrial scale.

But by merely showing that it can be done on a cooperative basis and without resorting to the extremes of the Daniels method with its “32 of the 34 required skills,” they are likely to inspire many more watch restorers and repairers – not just in England, but worldwide – encouraging others to take things to the next level and start making their own movements, cases, and dials. With or without the help of others.

For English watchmaking, Struthers Watchmakers could turn out be the reluctant acorn from which great things grow.

For more information, please visit www.strutherswatchmakers.co.uk/watches/project-248.

You may also enjoy:

Meet The Struthers: English Watchmaking The Old-Fashioned Way . . . Sort Of

Tracing The History Of My Grandfathers’s Pocket Watch And Delving Into English Watchmaking

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Dear Colin Alexander,

I enjoyed it a lot to read your article as a fresh update on p248 by Rebecca & Craig Struthers. Superb information and a closer look to British watchmaking and contemporary spirit. It is simply wonderful. After seeing the movement and even some dials, I can‘t wait to see the hands-set for this watch now. Thank you, best regards from Germany, Thomas

Glad you enjoyed it Thomas, thanks for taking the time to read it.

Great article, it’s nice to have an update on the Struthers. I’m certainly rooting for them!

They, along with Robert Loomes and Charles Frodsham, are, all on different levels of finish and price point, doing a lot of independent English watchmaking, outsourcing to local English craftsman where needed. It’s a model that is working and has a market, which I hope will only grow.

Yes, we all hope so too!

I would frame the handmade drawings. I don’t even have to see the watch. Handmade micro mechanics, It would be a dream to spend time watching this couple work. Thank you for an interesting article with a well written balance of technical and personal perspectives plus excellent photography. More please Colin. I could read the book you should write.

Thanks, Shirl, your comment made my day. And has made me take writing a bit more seriously! You have to thank Craig Struthers for the photos, though, all taken with an old iPhone 5 apparently.

Price?

If you have to ask, Gav….(as the saying goes)!

According to the bbc, they seem to be ~£50K. Fairynuff.

This is the best written and most interesting article I’ve read about British engineering and craftsmanship in a long while, and I’m an ex-FT tech reporter and columnist who’s written 100s of them in the past. I now produce a d’base of the top 70,000 UK smaller companies – many of them world leaders.

Bremont’s shop in South Audley St is two doors down from our offices. I hope the revival in UK craftsmanship is backed up and mirrored by a mass return of UK manufacturing of all kinds from China. We need to educate and employ tens of thousands of new, highly skilled manufacturing staff in companies great – and very small..

Thanks Marcus, your comment (like Shirl’s) above has made me look at writing in a more serious light. There is a strong groundswell of support for small independent manufacturing, that’s for sure.