by Ken Gargett

Somewhere in the disorganized depths of my cellar lies my favorite bottle. It is almost certainly not my best bottle, nor even possibly my most valuable – although without knowing prices, I could not swear to that.

It is a bottle that screams place and history. It tells a story and it links me to an extraordinary moment in time when three of the planet’s most famous leaders met to determine the fate of the world. All within the distance of a thrown grape from where this wine was being made.

And if there is one thing great wine does, it speaks of a place and time and tells a story.

The wine is the Massandra Collection White Muscat 1945.

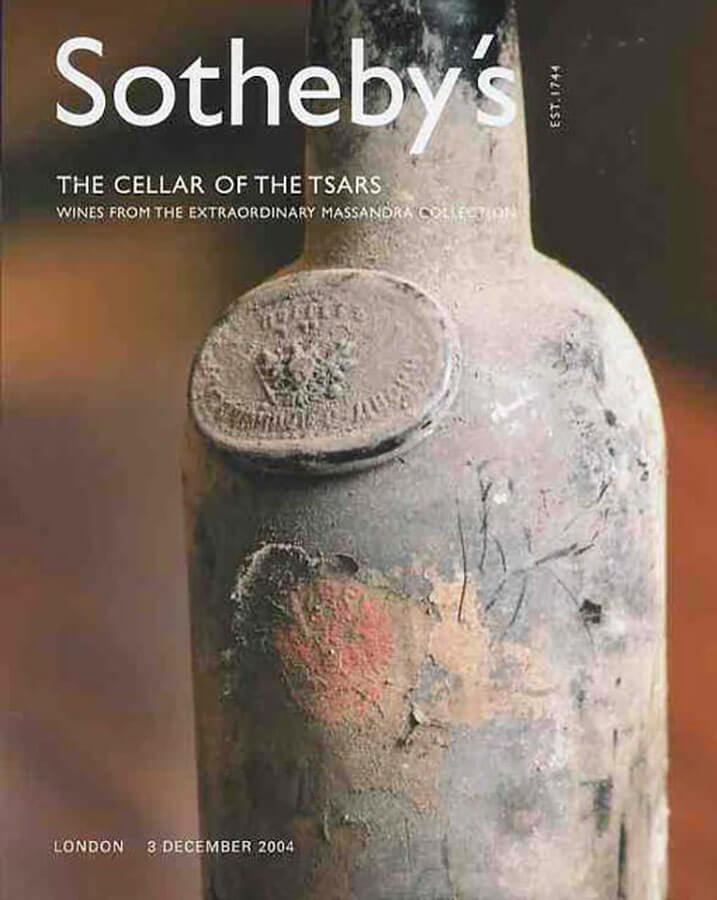

Sotheby’s 2004 auction of Cassandra Collection wines (photo courtesy Sotheby’s)

The winery is literally almost on the doorstep of the Livadia Palace where the Yalta Conference was held in 1945. I love the idea that as Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D. Roosevelt were determining the fate of the world, these vines were providing the fruit for this wine, grapes were ripening, and other vintages maturing in the amazing cellars.

Information about the Massandra Collection and winery is not easy to confirm, but it does seem likely that the vineyards on the grounds of the Livadia Palace actually provided the grapes for this wine.

I can’t recall where I got the wine or what it cost me – auction, I think, and not nearly as much as you’d think, I suspect. I have no idea when I will drink it.

I have tasted a number of the Massandra Collection wines over the years, but I remember the first most of all – don’t we always?

I was running late for a friend’s birthday lunch and as I charged into the restaurant, I was handed a glass of what looked suspiciously like an old fortified (this was many years ago and I had never heard of Massandra at that stage – nor had almost anyone else).

I thought this must be an ancient sherry served as an aperitif, but it tasted more like a wonderful old and marvelously elegant vintage port (the friend who had provided it has a cellar full of extraordinary ports so it would have been in keeping).

He once rang me to apologize as he had provided a bottle for the annual fishing trip debrief lunch. He had told us it was from the 1890s – no labels in those days of course, and the cork was not able to reveal exact details. Turns out that he had pulled out the wrong bottle from his cellar and he was very apologetic, though given what he brought us was from the late 1840s, it would have been churlish to chastise him.

I kept returning to the glass, trying to ascertain just what it was. Could it have been an old Rutherglen muscat? There was some sweetness, though it was not overpowering. The wine kept revealing more and more each time I returned to it.

Concentration, length, balance, a glorious wine. But I was getting no closer to its identity.

It turned out to be the Massandra Cahors Ayu-Dag from 1933. My friend had picked it up at an auction from a small parcel that had made its way out of Russia in the early 1990s.

Although labeled as a Cahors, a southwest French wine, it is actually more of a tribute to that style of wine, with the likely grape, according to some sources, a Ukrainian white grape called Kokur (sometimes called Kagor), which was a favorite of Tsar Nicholas and a sweet wine associated with the Russian Orthodox church.

I never believed that. They were also using Saperavi and this wine was red, surely not just from age. Research suggested that it was 15.4 percent with sugar registering at 184 grams/liter, but as I say information about these wines is very sketchy.

Massandra Collection wine Ayu-Dag Cahors 1938

What is Massandra?

Massandra is technically a Crimean winery, and one with an amazing history. The village of Massandra is near Yalta, and excavations have revealed that a winery was operating there before the birth of Christ and that muscat grapes have been grown locally for a very long time.

The Collection dates to 1823 and the father of the region’s governor-general, Count Mikhail Vorontsov (1782-1856). His father was the ambassador to London and developed a love of fine wine, which he passed on to his son.

Count Vorontsov ordered the building of a new winery – even today, his initials can be found carved into the stone drinking fountain. In 1829, he established the Magaratch Institute, similar to Bordeaux University and Davis in California, but predating them by a great many years. Today, it has more than 3,000 varieties in its experimental vineyards.

The actual palace attached to the winery took 80,000 serfs to construct, 20,000 of whom died during the process. So much for workplace health and safety. This was where Churchill actually stayed during the Yalta Conference. His room remains as he left it. Other reports suggest that it was Stalin who stayed at the winery.

Massandra history

In the 1870s, Prince Golitzin arrived to make “champagne” – he stayed until his death in 1915. While his wines did win a gold medal in Paris in 1900, overall they were perhaps not a huge success (my experience of sparkling from Russia and Georgia is that they are powerful but clumsy and far too sweet, though it has been a while since I have tried one).

In the 1890s, Tzar Nicholas II decided to make this the best winery in the world; the wines from the Livadia vineyard were served only to royalty. Georgian miners were brought in to dig a tunnel system on three levels with seven tunnels each of 150 meters.

Some of the history sounds more like Reilly, Ace of Spies or James Bond.

In 1898, Aleksandr Aleksandovich Yegrorov, who had made wine in Tbilisi and Azerbaijan, joined the prince to assist in making the wines. He was forced to flee during the Bolshevik Revolution, but his talents were such that he was subsequently asked back by the minister of food.

His daughter married a soldier, who turned out to be one of the tzar’s old colonels, which did not enhance his status, and in 1937 he was executed by Stalin’s secret police (presumably because winemakers are so often threats to national security). His son, in order to protect himself, had taken his mother’s maiden name. He ended up with a job, also as a winemaker, and by serendipitous chance it was at Massandra. He retired around the end of last century.

Golitzin came up with the concept of the Massandra Collection. It included the very best wines they were making as well as the best from around the world. The oldest wine in the collection is a 1775 sherry, of which there were apparently a number of bottles. The collection became the vinous version of Aladdin’s Cave.

Needless to say, a collection of the world’s finest wines was not the sort of thing that would normally survive a revolution such as occurred in Russia in 1917. It did so because the entrances to the various tunnels were blocked and hidden. This attempt at deception did not last long.

Fortunately, they had the most unlikely supporter – Stalin himself (perhaps he was secretly a “champagne socialist”). He liked the concept and, in 1920, ordered all the tzar’s wines added to the collection (or possibly it was in 1918 or even 1922 – like almost everything to do with this tale, there are numerous versions).

The next hurdle was World War II and the invading German army. As the Germans neared the winery, bottles were individually marked and packed, with the younger wines simply packed in crates.

The wines were shipped to three secret sites in Georgia just six weeks before the Germans marched into the winery. They had been forced to leave extensive bulk wines behind and the 1941 vintage could not be saved.

It is a local legend that the Black Sea was turned red as the Germans emptied these wines into it.

Other reports say that it was the Russians themselves who dumped anything they could not move or hide to prevent the Germans from getting their hands on them. This makes more sense to me. The one thing that the Nazis apparently did take from the winery was the guestbook. I have no idea why.

The Collection has been building steadily ever since, but in 1990 and 1991 a tiny quantity was allowed to be shipped to London to be sold at auction by Sotheby’s.

Subsequently in 1994, an English fan of these wines allegedly decided to bring a cache of them to London to sell. This sounds more like Arthur Daley and Minder rather than 007.

The buyer was apparently instructed to bring $50,000 in cash to the exchange. It was handed to a “gold-embossed Cadillac-driving Ukrainian nicknamed Mr. Big at a seedy airport hotel” (honestly, if you wrote that in a novel, it would surely be straight to the bottom of the clearance bin at the nearest airport).

After making the payment, the buyer headed to the winery at Massandra to collect his prized bottles only to be told no contract existed. The winery refused to part with any wine. Two days of negotiations achieved nothing.

The buyer tried to hire a local lawyer but was told that no such thing existed. All lawyers were in Moscow and they didn’t deal with such matters. And the cherry on top, as an outsider he was prohibited from dealing with local banks. Attempts to locate “Mr. Big” proved fruitless (there’s a shocker).

Eventually, the buyer accepted defeat and took the train west. To his great surprise, as the train approached Simferopol, the capital of Crimea, a truck appeared out of the blue carrying his wine – all of it. The buyer was able to get it as far as Kiev, but it took several more months of bureaucratic fun before he could fly it to London.

Since then, more orders have been fulfilled and these wines occasionally pop up on obscure sites, reliable specialist retailers, and at auctions.

The Massandra Collection

It is considered that the best wines in the Collection, of those made locally, are the fortifieds and the vins doux naturels. The winery also makes many wines that do not qualify for the collection.

Indeed, it is estimated that only one percent of the wines are considered good enough for the Collection. There are an estimated one million bottles in the cellars. The major market, by a long shot for the non-collection wines, is Russia.

Among the grapes used are Saperavi, Kokur, Aligote, Semillon, Verdelho, various muscats, Cabernet Sauvignon, Bastardo, Pinot Gris, and more, including the local kok pandas, a full-bodied white yet to reach household status outside the region.

As well as the famous vineyard at Livadia there is another vineyard at Balaclava, where there’s a monument to the Charge of the Light Brigade.

The Massandra Winery is a place where Russian leaders are often seen and photographed. As well as the tzar and Stalin, Vladimir Putin is no stranger, nor was Nikita Khrushchev. Outside leaders are also often taken there – Josip Broz Tito, Ho Chi Minh, and Silvio Berlusconi among them.

Massandra Collection sherry vintage 1775

Reputedly, Putin opened one of the 1775 sherries for Berlusconi. Others to visit included Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorky.

When President Mikhail Gorbachev implemented a vine pull scheme in the 1980s to combat Soviet alcoholism, the vineyards of Massandra were specifically exempted.

These days, the winemaking has taken a political turn with a pro-Ukrainian winemaker dismissed and the current director, a supporter of Russia, accused of treason (people do get excited about grape juice).

Gorbachev actually tried to arrange for a bottle from Ronald Reagan’s birth year as a gift, but it fell through (allegedly it got as far as the Kremlin, but after that its fate is unknown). A bottle of Bill Clinton’s birth year was given to an American businessman to pass on to Clinton – seems odd, given the usual diplomatic channels – but it is believed that the businessman could not resist and enjoyed it himself.

Another bottle of the 1775 sherry was sold in 2001 to a Malaysian buyer for £32,000. The next inquiry for a bottle met a price tag of €1 million. A not insignificant increase and one that, not surprisingly, was declined by the potential purchaser.

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 left the winery in Russian hands. Needless to say, Crimean authorities have not taken that well and there are suggestions of an attempted sale of the winery (value estimated around $250 million) or even nationalization.

The Massandra Collection is one of those delightful curiosities that make wine so fascinating. If you ever get the chance to try a bottle, don’t miss it.

A sense of place and a story to tell, indeed.

You may also enjoy:

Glorious Burgundy Is Experiencing An Unprecedented Golden Age Of Fantastic Wine Vintages

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

As always, an informative and enthusiastic read — thanks!

Given what the Nazis did in France, I would find it highly doubtful that they would have poured the wine into the sea. They knew and appreciated their wine….

As for “champagne” from the Crimea, I remember it well. This was — and still is, for all I know — the go-to tipple for cash-strapped German students. When I went to school there in the 80s, a bottle of this stuff was freely available in supermarkets, priced at around $2 a bottle (it is not much pricier nowadays), and we probably paid too much for it. The stuff was vile, a sugary bubbly confection whose alcohol content was its only positive quality.

Hi Alex. Many thanks for the note. Completely agree. Far more likely that it was the Russians themselves. Not sure we’ll ever get a definite answer though.

There is a wonderful book, ‘Wine & War’ by the Kladstrups, which is definitely worth a read – shows the Nazis hoarding what they can. Some wonderful stories in it.

Also agree re the sparkling. My experience was during a trip to Russia back in the mid 80s. Horribly sweet stuff. The trade off at the time was that you could buy buckets of caviar for next to nothing.