The How, What, When, Where And Why Of Seeing The Aurora Borealis, AKA Northern Lights

by Ian Skellern

My wife Brigitte and I had long harbored a wish to see the northern lights (aurora borealis), but had never really thought to make that dream come true. It was just something on the “nice to do” rather than the “to do” list.

But we serendipitously chanced upon “seeing” the aurora borealis while visiting Jackson Hole, Wyoming last year (see Give Me Five: Reasons To Visit Jackson Hole, Wyoming), and the excitement of that led to months of research.

And that research led more recently to spending a few days in the Arctic Circle in the north of Sweden.

Here is what I’ve learnt about the northern lights so far.

Why see the aurora borealis?

We may as well start off with the easy question first: why? We wanted to see the northern lights we because it is surely one of the most, if not THE most, spectacular events in nature. And if you don’t strongly believe that, then don’t bother as you are likely to be disappointed in the effort involved.

But be warned, unless you happen to live in a high-latitude location or are just plan lucky, your best chance of seeing the aurora borealis is to travel to somewhere near or ideally above the Arctic Circle when there are long periods of darkness.

Which means winter in or near the Arctic Circle, so that is likely to be both very cold and quite remote. And then there is no guarantee that the grand spectacle will actually perform when you are there. I would suggest that wanting to take photographs and/or video adds considerably to the motivation.

So when answering “why?” for yourself, do try and make sure that your motivation is strong enough to overcome what is likely to involve considerable hardship (like standing outside in winter in the Arctic Circle); time (the longer you are there the more chance you have of seeing something); expense; and quite possibly disappointment.

Aurora borealis photographed in Germany; note how bright the scenery looks for a dark night (photo courtesy Wikipedia)

And be warned that the incredible photos you see of the northern lights are likely to be much better than you will see in reality. This is because photos are taken at slow shutter speeds to maximize the amount of light hitting the sensor.

These two photos began the same way: if the eye detects any hint of color (as in the left image), then take a long exposure photo, add a little Photoshop – and voilà, a glowing aurora

This is recognizable by the fact that you can usually see the landscape quite clearly as though it is early evening or strong moonlight even though, in reality, the night is likely to have been absolutely pitch black where the photo was taken.

What are the northern lights?

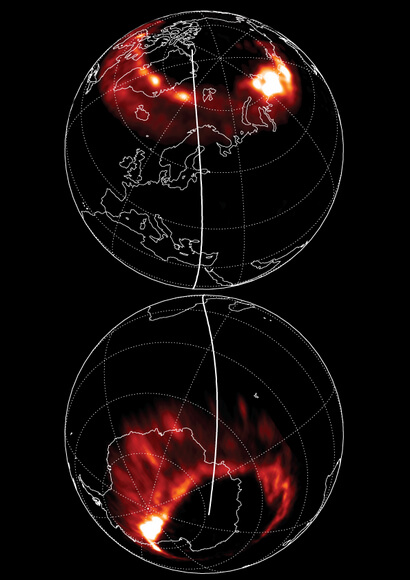

First, I should make it clear that the southern hemisphere has its own equally impressive solar-powered light extravaganza called the aurora australis over the South Pole.

Auroras are visible in both the north and south poles (image courtesy Karl Magnus Laundal and Nature)

But as remote as the Arctic Circle is from North America and Europe, it’s an easy commute compared to getting to Antarctica. And while particularly energetic solar outbursts can manifest themselves as far north (from the South Pole) as southern Australia, it’s generally easier to see auroras in the northern hemisphere.

But what exactly creates these intense lights?

Well, basically they are the result of two magnetic fields: that of the earth and that of the sun.

Let’s look at the sun first (though not literally).

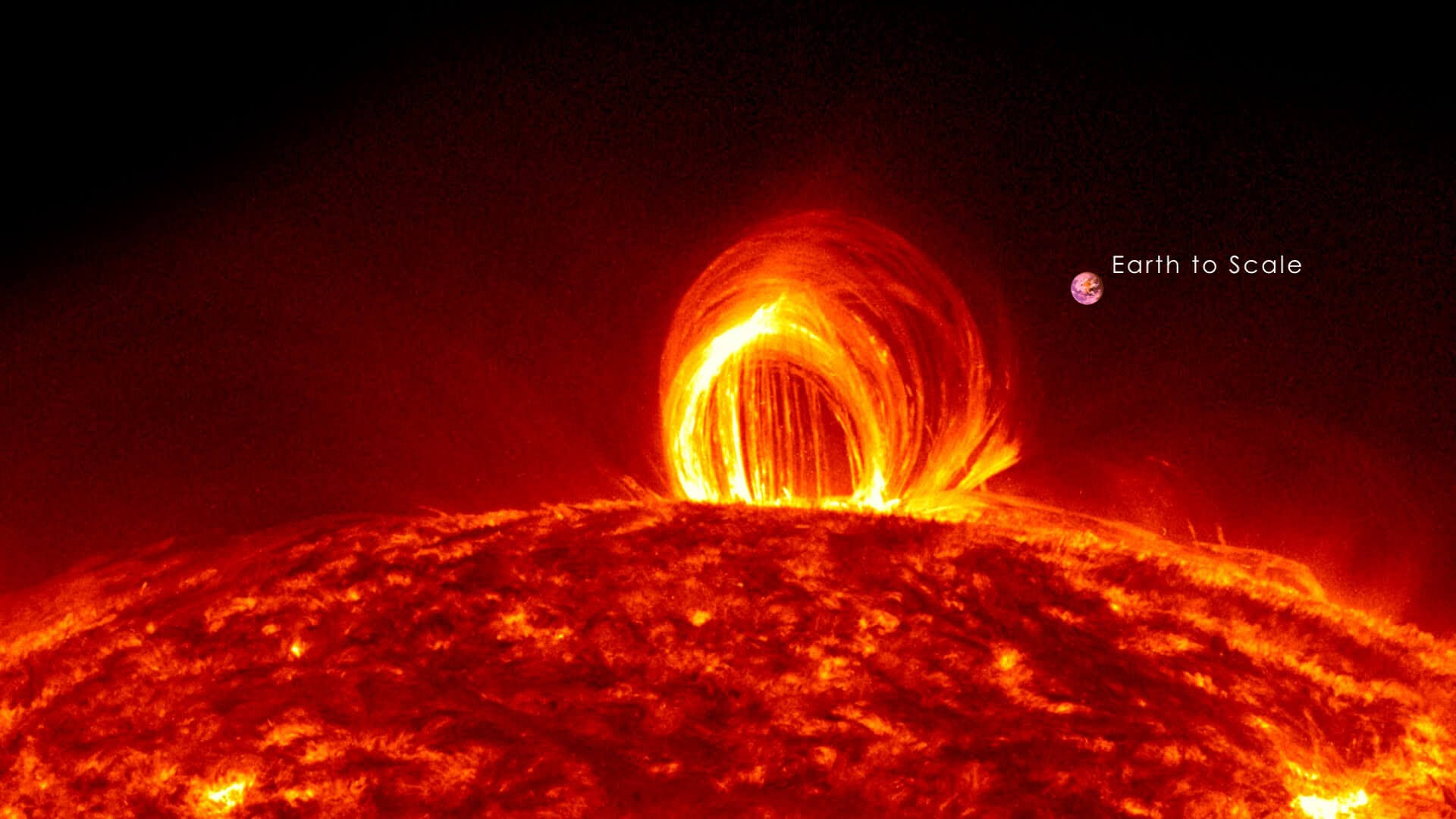

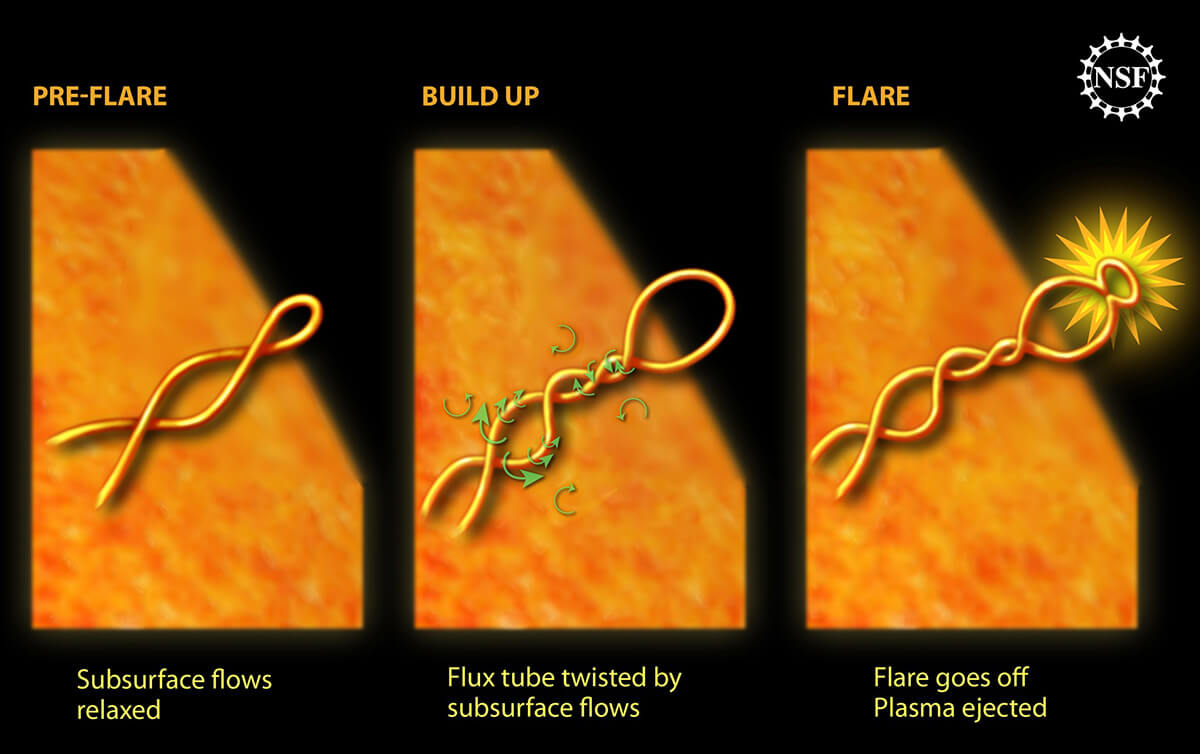

Unlike the earth, the sun is not solid. It is a big ball of hot gas (mainly 70 percent hydrogen and 28 percent helium) with a giant nuclear fusion reactor at its core. Powerful magnetic fields are generated and these wrap and weave in and around the sun like giant rubber bands.

And sometimes these massive twisted bands of magnetic fields snap, releasing a torrent of highly charged particles. And if this happens to occur on the side of the sun facing the earth, that massive stream of charged particles will travel 150 million kilometers toward earth, where most will be deflected by our planet’s own magnetic field.

The release of this energy causes sun spots, which are areas on the sun that are darker because they are cooler due to the energy lost in the sudden release of charged particles.

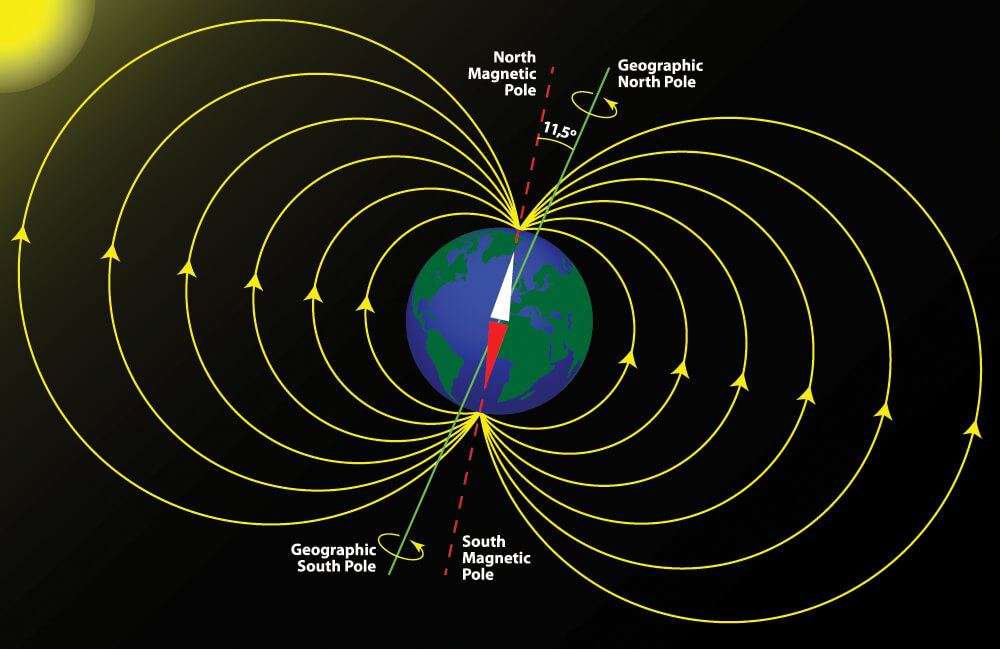

The earth’s magnetic field, which is created by our planet’s molten iron core, is relatively stable compared to than of our sun; however, it does manage to flip north and south in a geomagnetic reversal every 500,000 years or so.

And without this magnetic field, which protects us from much of the solar wind, which is a constant stream of radiation, the earth would likely be a barren wasteland stripped of its atmosphere – much like Mars today.

The fact that you are reading this is proof of just how great a job the earth’s magnetic field does in deflecting solar-charged particles around our little planet.

In fact, the only places that these charged particles can enter our atmosphere are at the poles, where our protective magnetic field is weak.

The auroras are created when highly charged particles generated by solar flares travel more than 140,000,000 kilometers, slip in through the earth’s weak magnetic defenses at the poles, and enter our atmosphere.

If they are energetic (highly charged) enough, these solar particles will create light when they hit oxygen atoms (green) or nitrogen atoms (blue and red).

How + when + where

Actually seeing the northern lights is all about maximizing your chances of seeing them, and this is what is involved.

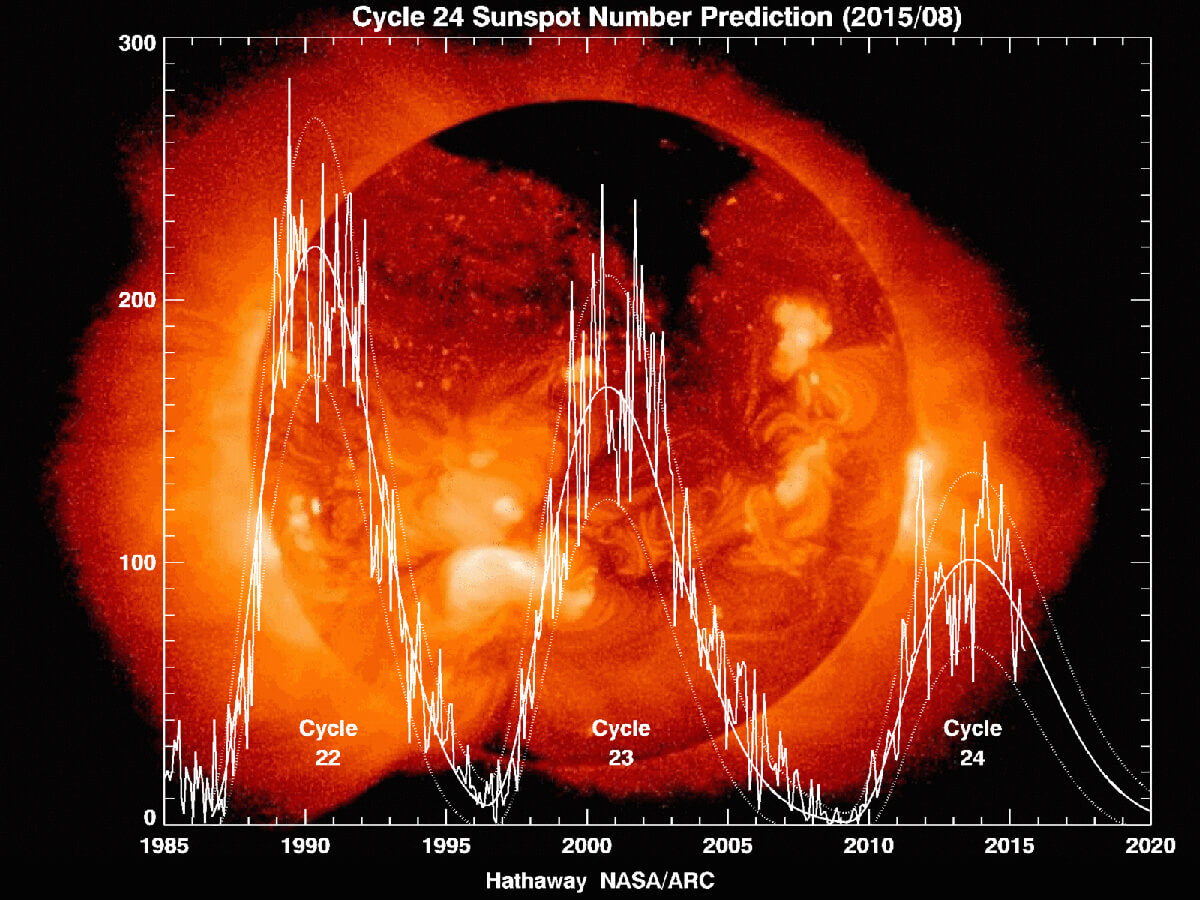

Recent solar flares need to have generated the stream of charged particles. While the sun constantly creates solar flares, the amount of flares generated ebbs and flows in an approximately eleven-year solar cycle. We are now coming off the peak of solar cycle 24, which started in 2008, meaning that you should either plan your trip as soon as you can (winter 2016 or 2017) or wait until around 2025 when the next cycle is due to peak.

While the aurora borealis has been seen as far south as Louisiana and southern Europe, and they can even be seen in daylight, that’s only likely to happen when particularly large solar flares release their energy in just the right direction at just the right time. So chances are against that happening.

To increase your chances of seeing the northern lights, you want to be somewhere where you can see them even during relatively mild solar flares, which are much more frequent than large flares.

The earth’s magnetic field is weakest at the poles and gets stronger the further you are from the poles. So the closer you are to the North Pole, the more likely you are to see the aurora borealis.

And you will want as much darkness (or as little ambient light) as possible because it is easier to see a faint light against a black background than against a light background. So avoid large towns and cities as all of that light pollution is likely to drown out any auroras.

And avoiding light also means avoiding daylight. You have more chances of seeing auroras at night, so the longer the night, the better the odds. Luckily, Arctic winters are as well known for their length as their severity.

Wintertime – October to March inclusive – in or near the Arctic Circle is about perfect.

One other thing to take into consideration is weather. Auroras usually occur around at an altitude between 80 and 600 kilometers above sea level. And while thin or broken clouds can make for incredibly spectacular auroras as the clouds are illuminated as well as the air, if there is too much cloud you see nothing at all.

Where is best for you to have a good chance of seeing the northern lights depends on where you live and how much time and money you want to devote to the adventure. And make no mistake, a trip to see the aurora borealis is likely to be more of an adventure than a relaxing holiday.

So where did we go and what did we see?

If we lived in North America, we would likely have been looking at trying to see the northern lights in Alaska. However, as we live in Europe, we chose to travel to Abisko in Sweden, 250 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle.

That involved flying first to Stockholm, then another flight to Kiruna in the north of Sweden. While Kiruna itself is a popular destination for aurora seekers and is nicely situated around 150 kilometers inside the Arctic Circle, we traveled another 100 kilometers further north to the small village of Abisko because it benefits from a relatively dry micro climate that results in more clear skies.

Norway, Finland, and Iceland are also worth considering if traveling from Europe.

Due to time constraints we only had four nights in Abisko and it went like this: we arrived in Abisko around 9:00 pm; we saw the northern lights around 11:00 pm and I took three quick photos. And we did not see any auroras again (but we did do some trekking and mushing).

Nighttime temperatures dropped to minus 20°C (-4°F) and can get much colder; the lack of sleep was tiring; and the hotel (Abisko Mountain Lodge) was basic (though clean, great staff, and excellent food). There are quite a few hostels in Abisko, and the STF Abisko Mountain Station is also worth checking out.

Summary

- Plan on staying a week to give yourself as much chance as possible to catch the lights. Take clothing suitable for spending long periods of time being relatively inactive outside at very low temperatures.

- Take a decent camera, wide-angle lens, tripod and, if you can, a time-lapse remote. And make sure you can comfortably use the camera in the dark and cold before the sky explodes in light.

- Make sure that there are other activities in the area like trekking and mushing in case aurora activity is low.

- Your sleep will be disturbed as you will be up much of the night. Auroras, if they appear at all, may only be visible for a few minutes during any night and you will miss them if you are in bed (unless you are sleeping under a glass roof).

- And don’t get hung up on checking the aurora forecasts as they are rough guides only. Auroras often appear when they shouldn’t and don’t show when they should.

I’m not a particular fan of cold weather – tropical beaches are more my style – I am quite fond of having a good night’s sleep and we “only” saw the auroras for one night out of four.

So was it all worthwhile? The best answer to that is the fact that we are already planning our next trip back to Abisko.

For more on seeing auroras, you may find these websites interesting:

When is the best time to do Aurora Photography ?

General advice: www.aurorahunter.com/aurora-prediction

27-day aurora forecast: www.swpc.noaa.gov/products/27-day-outlook-107-cm-radio-flux-and-geomagnetic-indices

One-hour aurora borealis forecast for Europe: www.aurora-service.eu/aurora-forecast/

One-hour aurora australis forecast for Australia/New Zealand: www.aurora-service.net/aurora-forecast

Check out the iPhone app Northern Lights Photo Taker

* This article was first published on March 1, 2016 at The How, What, When, Where And Why Of Seeing The Aurora Borealis, AKA Northern Lights.

You might also enjoy:

Give Me Five: Reasons To Visit Jackson Hole, Wyoming

Car And Watch Spotting In Havana Starring A Cartier Santos Dumont And Beautiful Old-Timer Cars

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!