by Ashton Tracy

Humans have long had a fascination with the depths of the ocean, striving to go ever deeper, ever further, and ever faster by pushing the limits of the human body, technology, and advancing modern science.

But like all things, we humans are faced with limits.

Deep-sea divers used to face these limits when underwater for long periods. During time underwater tissue absorbs gases, and the time needed for ascension to the surface can take many hours, even when only exposed to certain depths for a few minutes.

Lengthy decompression times posed a problem for divers needing to spend prolonged periods of time at depth; and every decompression comes with risks as well. A solution was needed.

In 1957 Dr. George F. Bond, a United States Navy physician, began the Genesis Project, a medical experiment to study the effects of exposing animals to various breathing gases at different underwater depths to observe the effects on their bodies.

The experiment proved that bodies reach a saturation point and no more time to decompress is needed once this has been reached, regardless of the time spent underwater. Throughout the project, different mixes of gases at different depths were used and it was observed that if the majority of the breathing gas was helium, all the subjects survived at varying depths for different lengths of time.

In 1962 human trials began at a gas mix of 21.6 percent oxygen, 4 percent nitrogen and 74.4 percent helium. With these trials proving successful, a world of opportunity had now opened up with divers being able to live and work for periods of 30 days at depths of 600 feet.

This somewhat unknown experiment changed the horological landscape forever, producing one of the most confusing and recognizable features of dive watches today: the helium escape valve.

Rolex Oyster Perpetual Sea-Dweller Deepsea D-Blue with helium escape valve

Sealab

After the success of the Genesis project, the United States Navy launched Sealab, which was also headed by Dr. Bond. Sealabs (I, II, and III) were experimental underwater habitats developed by the U.S. Navy in the 1960s to prove the viability of saturation diving as well as humans living in isolation for extended periods of time. Sealab I ran into some technical problems due to an approaching storm, with the experiment canceled after 11 days. Sealab II and Sealab III soon followed with more successful results.

These underwater habitats were pressurized living quarters for divers, providing a mix of breathing gas composed mainly of oxygen, nitrogen, and helium. The Sealabs included a sleeping area, bathroom, and living area and ensured that divers could spend multiple days at a time underwater performing all necessary tasks without having to make time-consuming, dangerous ascents on a regular basis.

Helium escape valve

During ascents in diving chambers, it was noted that from time to time the crystal from one of the divers’ watches would pop off with a loud bang.

This was attributed to helium buildup in the case, which makes its way in via diffusion by penetrating the rubber gaskets.

As the diver ascends in the chamber, the gas pressure outside of the watch decreases, with the pressure inside of the watch remaining higher. Once the difference is too great, the pressure buildup causes the crystal to pop off the watch because crystals were generally simply friction fitted on dive watches of the 1960s.

Rolex decided to tackle the problem head-on and introduced what it called the gas escape valve, a one-way pressure-release valve that allowed the helium to escape the case once the pressure difference reached a certain amount.

This valve was incorporated into the now-loved Rolex Sea-Dweller. On the Sealab III mission, Rolex Sea-Dwellers equipped with gas escape valves were issued to the diving team, thus solving the problem of helium entering the case.

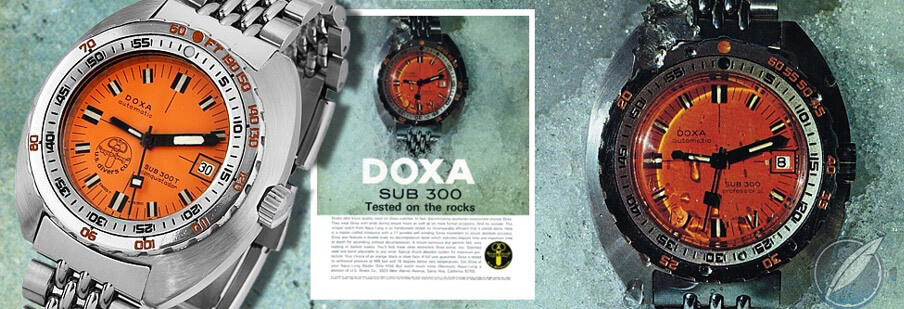

Advertisement for the Doxa Sub 300T with helium escape valve

At the same time Rolex was developing its gas escape valve, the Doxa watch brand was also involved with its own project. In 1964 Doxa teamed up with several professional divers, one being Claude Wesly, who was part of the legendary Jacques Cousteau dive team, having taken part in the Precontinent I, I, and III dive missions similar to Sealab carried out by Cousteau and his team.

While Rolex was focused solely on commercial applications, Doxa’s goal was making an affordable dive watch for recreational and professional divers.

Rolex and Doxa enjoyed a good relationship and the decision was made to share the patent for the helium release valve.

Michael Phelps’s personal Omega Seamaster Planet Ocean 600M Master Chronometer Chronograph as photographed in Rio de Janeiro during the 2016 Olympic Games; it too has a helium escape valve

Conclusion

The history of helium escape valves is definitely an interesting one, with humankind once again proving it will stop at nothing to conquer the unknown.

And, as always, the watch industry was at the forefront of helping boundaries to be pushed.

While the average consumer doesn’t really need a helium escape valve fitted to his or her dive watch, it is a wonderful piece of diving history to carry around.

Average consumers don’t need watches that can reach depths of 3,900 meters or keep time to within two seconds per day; nor do they need cars that can reach top speeds of 300 kilometers per hour. But that isn’t the point.

The point is you can have those things because humans can make them. These feats of human engineering and ingenuity are what push us to go further, faster, longer, and higher.

So I say, long live the helium escape valve.

* This article was first published on March 18, 2018 at Deeper, Further, Faster: Why Do Some Dive Watches Have Helium Escape Valves?

You may also enjoy:

All About Automata: Mechanical Magic (With Action Videos)

Fast vs. Slow, Hertz vs. VPH: Your Watch’s Frequency Explained

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!