Hailed the “Prince of Languedoc” for the quality of his wines, acknowledged as some of the best from this French region known for its Cathar castles and Cistercian abbeys, Gérard Bertrand has been instrumental in elevating the image of wines from the south coast of France, a region once dismissed as making mass-market products.

Gérard Bertrand Art de Vivre red wine (photo courtesy Gérard Bertrand/Marie Ormières)

Among the top French brands imported into the United States today, Bertrand has converted all 16 of his wineries to biodynamic standards – and with 850 hectares, Gérard Bertrand is the largest producer of biodynamic wines in the world.

The third generation in a line of winemakers, following in the footsteps of his grandmother Paule and his father Georges, the Narbonne-born 55-year-old has been at the head of the family business since 1987 following the sudden accidental death of his father. He first took over Château de Villemajou at the age of 22 before a buying spree of wine estates – while also pursuing a professional rugby career. He played for Racing Club Narbonne Méditerranée and became team captain at Stade Français Paris Rugby before retiring in 1994 to concentrate fully on wine.

Gérard Bertrand Domaine de Villemajou

“I was a rugby player, and I had to manage both rugby and wine for eight years,” Bertrand recalls. “That means I worked 60 hours per week in the vineyards and on top of that, I prepared myself for the rugby season. We played 40 games a year, and I lived like a monk for almost eight years. I was exhausted by the time I was 30. When I stopped playing, I decided to develop my wine career and had the idea of buying another estate, Cigalus, and to create a house for my family because I had just fallen in love with my wife, Ingrid. I decided to rebuild this place because it was more or less a ruin. It was the beginning of the journey and we bought another estate in Minervois: Château Laville Bertrou.

“I decided to create Gérard Bertrand Wines as an umbrella; I had been inspired by visiting Mondavi in California, Antinori in Italy, and Moueix in Bordeaux,” the winemaker continues. “My idea was to promote the south of France as a destination, and this is what we have done, but it was a long journey. For 25 years it was a big battle because the south of France was not yet on the world wine map, and it was important for me to say you have another region to put on your list. Now we are the leader and the first French wine in the U.S. market. We are number two in Canada. We are number one for biodynamic farming, which we started at Cigalus.”

Gérard Bertrand: nature knows best

For Bertrand, nature knows best. Having completed his first vinification at the age of 10, working in the vineyards has always come naturally to him. But he found his true calling through biodynamic viticulture – an approach to sustainable, organic farming that follows holistic principles and ecologically ethical practices – striking the perfect balance between humankind and nature.

Gérard Bertrand in one of his vineyards in Languedoc, France

Questioning how the moon and the planets and their interplay with the rocks and limestone in the soil impact the taste of wine, Bertrand understood that a great wine is connected to the universe that surrounds it.

A longtime proponent of homeopathic medicine, in 2002 Bertrand decided to put Rudolf Steiner’s teachings in biodynamic agriculture to the test. Together with his head of biodynamic viticulture, Gilles de Baudus, he began secretly experimenting with four hectares of vines at Cigalus. They split the plot in two: one to farm biodynamically and the other using their usual sustainable agriculture approach.

They applied silicon-based products and plant mixtures including yarrow, oak, dandelion, and nettle as tinctures, guided by the forces of the earth and the cosmos. The influence of the moon, sun, and stars during a plant’s growth cycle is key, especially the inner planets and celestial bodies closer to the sun (the moon, Mercury, Venus, and Mars), and to a lesser extent the outer planets (Jupiter and Saturn).

Gérard Bertrand Château l’Hospitalet 2017 (photo courtesy Gérard Bertrand/Marie Ormières)

The various moon phases dictate every action throughout the winemaking year, from harvest to vinification and aging to bottling. Two years later, the benefits of biodynamic farming became clear: fewer diseases, no need for chemical products, more diversity of nature in the vineyards, grapes of greater freshness, vitality, and minerality with a more intense taste, better wine quality with more aging potential, better balance, and much more energy in the glass.

“You don’t need a glass of wine to stay alive,” Bertrand states. “When you drink a glass of wine, it’s for pleasure, emotion, or sharing. We don’t have to make any more compromises with nature, the soil, or subsoil. My philosophy is to respect the ecosystem, biodiversity, and to leave a better planet for the next generations.”

While organic production creates healthy, natural wines that taste good and have high nutritional value, biodynamic farming goes a step further by considering the soil as a self-contained living organism that must be respected and regenerated deeply.

It injects a spiritual dimension between humans and the land, raising awareness of how we relate to our environment and connecting us with the forces of nature. “We are all connected, and we want also to share the message that nature is stronger and more intelligent than us,” Bertrand explains.

“That means we have to understand and follow the rhythm and biorhythm of the cosmos and nature, to open our mind, soul, and vision. You see the beauty and perfection of creation, and you understand that in the planet, you have all the ingredients to save a plant against illness. This is what we do, and it’s worked. Now we have great expertise and more than 100 people dedicated to this program. You feel that nature is happy, which is important, and you can get that also in a glass of wine because the energy is there. You cannot measure the energy in a glass of wine, but you can feel it. That means you move from only measuring something to feeling it.”

Gérard Bertrand Château l’Hospitalet (photo courtesy Gérard Bertrand/Gilles Deschamps)

Gérard Bertrand: Languedoc as a wine region

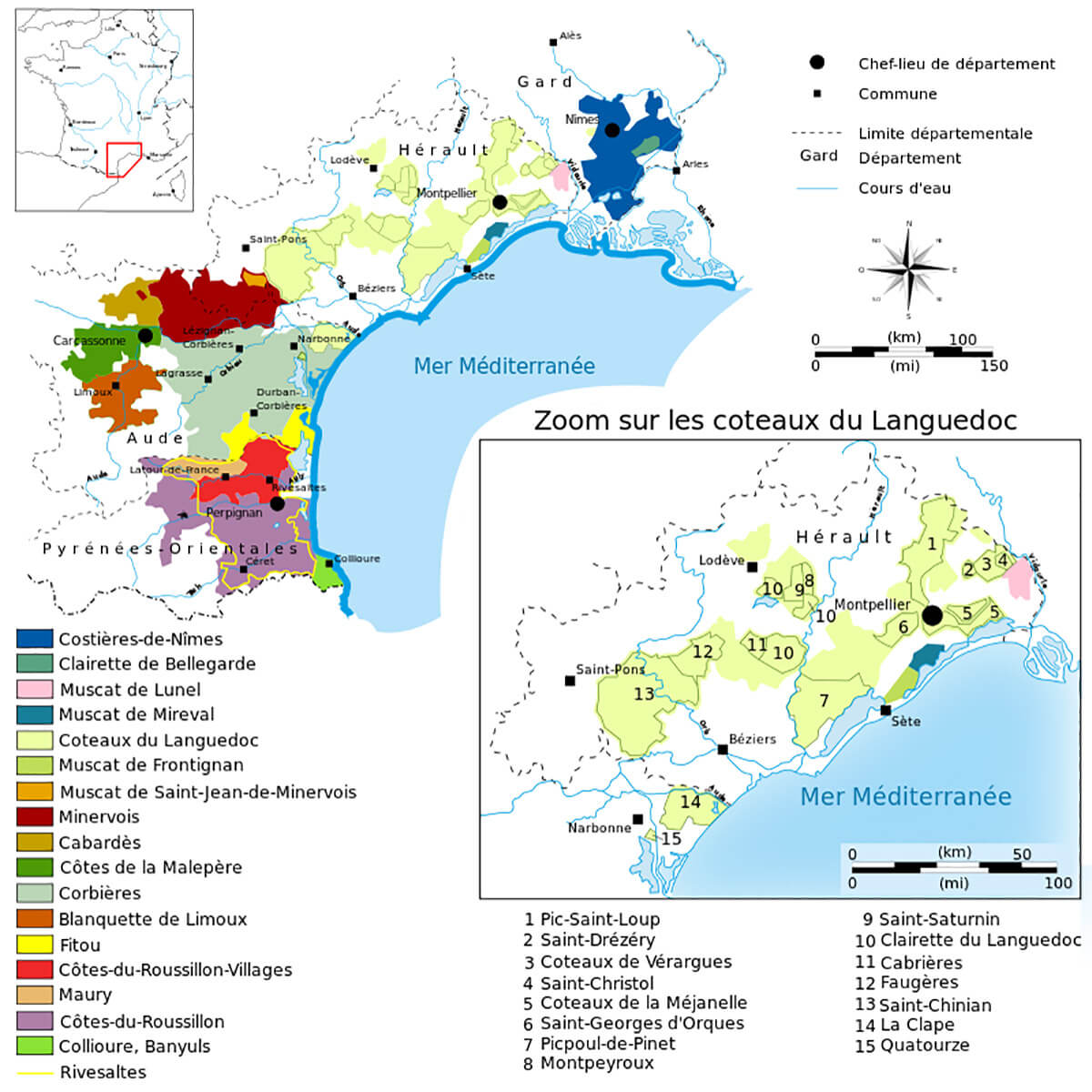

Bertrand touts the merits of biodynamics as the best way to bring out the typical character of a terroir while respecting the environment and biodiversity. Thus, his wines embody the varied tastes of Languedoc-Roussillon – the world’s largest winemaking region – which stretches from Montpellier to Perpignan and from the Mediterranean Sea to the Pyrenées Mountains, encompassing wide-ranging terroirs through his wineries Clos d’Ora in Minervois La Livinière, Château de La Soujeole in Malpère, and Château La Sauvageonne in Terrasses du Larzac.

After several blind tastings by professional wine tasters comparing tens of thousands of samples from across the globe, his Château L’Hospitalet Grand Vin Rouge 2017 was named Best Red Wine in the World at last year’s International Wine Challenge competition.

Drinks Business magazine labeled Clos du Temple 2019 – with its marvelous blend of cinsault, grenache, syrah, viognier, and mourvèdre for a true Mediterranean identity – the Best Rosé in the World (it is also the most expensive still rosé on the planet with a magnum costing $390), proving Bertrand’s wines are able to rival those from France’s most renowned châteaus.

Gérard Bertrand Clos d’Ora vineyard in Languedoc, France

“To move from a great wine to an excellent wine, the difference is the terroir,” Bertrand notes. “Through Clos d’Ora, Clos du Temple or single-vineyard estates like La Forge or L’Hospitalitas that have unique terroirs, we deliver a sense of place, which means the message and the taste of somewhere. And then to go from an excellent to an exceptional wine, this is not anymore a question of terroir, but one of weather conditions during harvest.”

He has a particular soft spot for Clos d’Ora (a bottle of the 2016 retails for $250) set in a mystical location at 220 meters altitude enclosed by dry stone walls and housing an old sheepfold. He bought it in 1997 before deciding a decade later to transform it into a winery, having identified the potential of a great terroir.

Gérard Bertrand Clos d’Ora 2015 AOP Minervois La Livinière

“I fell in love with the beauty of Clos d’Ora, which is above a geological fault,” he discloses. “You can feel a strong connection with the cosmos.” The land had spoken to him and serves as a place for meditation and quiet reflection. Having the luxury of time, it was only in 2014 that the first vintage of Clos d’Ora was released.

Languedoc wines: long uphill battle to eliminating preconceptions

“My father was very wise because he was one of the first to understand the potential of the area and to have the ambition to reveal the region’s terroirs: Fitou, Corbières, Minervois, Saint-Chinian, Tautavel, and so on,” Bertrand divulges.

In the 1960s and ’70s, the Languedoc region produced table wine in bulk as demand was so high that winemakers focused on quantity rather than quality (the French were drinking from 150 to 500 liters annually). Bertrand’s father was among the first to believe in the terroirs’ possibilities.

Ahead of his time, it was important for him to explain to his peers that they had to change behaviors, reduce yields, pick grapes later, and start to create a new winemaking process. In the ’70s and ’80s, his father convinced producers to bottle their best cuvées and to begin to promote and sell them.

Then wine fairs in France launched to push Languedoc as a destination, and it was the commencement of the journey – with a real shift in the image of Languedoc wines debuting three decades ago.

“Languedoc has experienced a qualitative evolution for more than 30 years now with the creation of many AOPs (Protected Designation of Origin) guaranteeing the quality of the wines and the seriousness of the Languedoc winegrowers,” says Guillaume Barraud, deputy director of Gérard Bertrand Domains.

“These appellations (Languedoc, Limoux, Terrasses du Larzac, La Clape, etc.) have been defined by a detailed identification of the terroirs and by the emergence of dynamics of determined actors, who were able to come together very early on to bring out the quality of Languedoc wines and have them recognized at an international level. Our ambition has always been to showcase the most beautiful terroirs of Languedoc. This approach has therefore been found in particular in our iconic wines such as Clos d’Ora and Clos du Temple, but also in the parcels, which was to carry out a work of precision from the vine to the bottle to sublimate the grapes produced from these terroirs. It is the art of 1,001 details that make them excellent wines that can compete with the greatest wines from around the world.”

For more information, please visit www.en.gerard-bertrand.com.

You may also enjoy:

Glorious Burgundy Is Experiencing An Unprecedented Golden Age Of Fantastic Wine Vintages

Château Thivin Beaujolais: Burgundy’s ‘Little Sibling’ Offers Serious Wine With Joyous Exuberance

Domaine Dujac: Red-Hot Burgundy Wines (With Tasting Notes)

Clos De Tart And Clos Des Lambrays: The Glory Of A Great Burgundy Is The Pinnacle Of Wine

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

His wines are good, but I can’t really get past the totally anti-science ideology of anthroposophy. Of course, he also had to be a supporter of homeopathy…

You can easily separate those two ideas. Homeopathy has absolutely nothing to do with anthroposophy; they were founded by two completely different people and are based on completely different concepts – and none of it is “anti-science”; it is just from another century and based in nature, not chemical. Anthroposophy is used by many in the winemaking industry today and contains only things that are good for people, found in nature. Honestly, I don’t see how anyone can be against it, especially if it is only making something better (better tasting, better for the planet). But you’re going to need to get used to it because it is a growing movement in wine gaining a great deal of traction. You are probably already drinking plenty of biodynamic products and don’t even know it!

I drink biodynamic wines and I know exactly when I do, because I know that lots of winemakers are sincere and it does not prevent them from working correctly. But the fact that it is a growing trend is by no means a proof that is works.

They are making the same error as you seem to do, which is mistaking biodynamy for organic farming. Biodynamy and anthroposophy are a system of new age beliefs, akin to a religion, which is absolutely not a problem in itself, but it starts to be a problem when it disguises as a science and fools farmers and consumers alike, which is why I call it antiscience.

The wikipedia page on biodynamic agriculture (sections effectiveness and reception in particular) are a good starts as they are well sourced. You can also read about Rudolf Steiner who was an ideologist, neither a farmer nor a biologist, and did not rely on what is commonly accepted as the modern scientific method (hypothesis – test – results – replication, etc.)

The only reason why many biodynamic wines are good is because organic farming seems to have good results on wine, and because biodynamic winemakers are in general passionate or meticulous. But that cosmos thing, the root and fruit days and the obsolete epistemology of a not-so-good 19th century “scientist” has very little to do with it.

I know precisely the difference between organic and biodynamic and am extremely well acquainted with Steiner and his philosophies as well as how they are applied in various ways and industries today. But I also know that biodynamic is mostly organic. And if the rest – which is also not chemical, but natural, in base – doesn’t hurt anything, who cares as long as the wine is good? I know and understand everything you just mentioned. But what I don’t understand is why get upset over it if it isn’t adversely influencing anything. In Bertrand’s case, he believes it makes his wines better. You say his wines are good. I think if they are natural/organic in base, I’d give them a try (I’ve never had them; Burgundy isn’t my preferred wine). So what does it hurt? That’s my question to you.

I’m not going to touch the rest of this as it doesn’t apply to this discussion, and I do thank you for discussing. It’s a not-unimportant topic to me.

It seems that we actually don’t really disagree, because as I said, I happily buy and drink biodynamic wines. What I don’t like is non-sciences pretending to be sciences, because it entertains a confusion in the mind of non scientifically trained people, on subjects more important than good wine, such as health, medicine, climate or many others.

I understand this is slightly off topic, and once again, I don’t have a problem with biodynamic wines, but I am a little uncomfortable with a website, although not a science website, reproducing the claims about the benefits of unproven things without any step back. Most of the articles on this website about watches are very well documented and scientifically sound, and that gives you a certain authority which becomes slightly dissonant here.

And by the way, I know biodynamy is harmless, and I rather support organic farming for other reasons, but there is no link whatsoever between being natural and being harmless. I would happily drink a bucket of artificial vanilla extract (made from oil so you could have other very good reasons to refuse to eat it, but it is not dangerous for our health) before I agree to eat a single piece of a death cap mushroom. And I guess anyone would do the same.

To be even clearer: I enjoy this website and am happy that there was an article about this excellent winemaker. I just wanted to add some contradiction about what is claimed, because of my science ethics.

I understand where you are coming from and thank you for the discussion, especially since it was over wine and not watches! I do hope we can have a better wine discussion some day with a few well-chosen bottles in front of us.

Just for information, Y-Jean spent several days visiting Gérard Bertrand’s domains (she lives in France) before writing this article. I don’t think she wrote it in the frame of mind that Bertrand’s methods are a “science,” but rather providing information on the processes used there. Personally, I cannot tell whether she believes in it or not from the text – and in the best-case scenario I shouldn’t be able to. Like a good journalist, she is providing the facts herself and letting Bertrand’s quotes provide the color and opinion. The article was never intended to be scientific, but rather to inform and entertain (the goal of good journalism and the practice we try to subscribe to here).

But I will step in and say I am not uncomfortable with the topic of anthroposophy because it is one of the theories that I partially use to make up the very complicated whole that is my personal philosophy. I am one of those people who picks and chooses the best parts of what is out there to give myself a framework of things to work with that are good for me, good for the people around me, and good for the planet. So while I use all-natural and carefully produced cosmetics from Dr. Hauschka (anthroposophy/Steiner) and I take homeopathic remedies for some things (Hahnemann), I vaccinate and I would never rely on a mistletoe tincture to cure cancer (allopathy). So I think it is quite possible to be less black and white when it comes to some things – much the same way some people might look at an Urwerk watch and exclaim “What in the world is that?!” while pulling a disapproving grimace (which I would be able to understand only marginally). I feel fortunate that our world offers so many different ways to see and do things. Agree?