Trimbach Clos Sainte Hune: The World’s Best Dry Riesling

by Ken Gargett

Riesling is a polarizing grape. Some are besotted by it. Others, not so much. My sister stubbornly refuses to touch it, claiming she does not like sweet wines.

Fair enough, but even when I give her a bone-dry example of the type that places in Australia like the Clare Valley and Eden Valley do so well she won’t have a bar of them, convinced that they are sweet in disguise. Such is the power of suggestion. Years of fine wine have been wasted in my efforts to convince her otherwise.

Riesling is undoubtedly an allrounder, with wines ranging from throat-crackingly dry to hedonistically sweet and everything in between. It can be delicious when young and amazing with age. Very few wines can compete with it in terms of cellaring. The oldest wine I have ever tried was from the early 1700s – it was a Riesling and still fascinating, if perhaps a touch past its peak.

One of the world’s most famous wine critics, Jancis Robinson, is a well-known fan of the variety, describing it as the “greatest white wine grape” and stating that “top-quality dry Riesling, wherever it comes from, is a truly thrilling drink.” No disagreement from me.

Riesling is also the perfect variety through which to reflect terroir (Pinot Noir plays a similar role for reds). Rather bizarrely, the only place in France where Riesling is officially permitted is Alsace.

As a very broad rule of thumb, German Riesling is sweet through varying levels; Alsace is dry; Australians are dry; Washington State and Oregon can offer a broader range; and from New Zealand, Rieslings can tend to the drier end of the spectrum but do need sweetness to balance the sometimes fearsome acidity. But every region has exceptions, often many of them.

Winesearcher often runs an eye over the most wanted examples of certain varieties, assessed by the number of searches on the site (I am assuming it has something to do with whatever algorithms do, but in truth I haven’t got a clue). In its latest exploration of Riesling, the top ten all have average scores of 92 and higher, while prices ranged from $55 to $8,486. Eight of the wines were from Germany, featuring such superstar makers as Dönnhoff, Joh. Jos. Prüm, and Egon Müller. Two were from Alsace, both from renowned producer Trimbach.

Trimbach Estate vineyards in Alsace, France

The two Trimbachs were the Cuvée Frédéric Emile (third) and, in first place with more than twice the searches as the second wine (which was JJ Prüm’s Wehlener Sonnenuhr Riesling Auslese from JJ Prüm), Clos Sainte Hune, generally acknowledged as the finest dry Riesling on the planet. It is a highly sought-after wine and usually priced around the $300 to $500 mark.

A little Alsatian history

Alsace is a region currently in the east of France – over the decades, “ownership” has largely depended on whichever nation won the last Franco-German scuffle – that produces superb white wines, usually labelled varietally, which is a very un-French thing to do. A considerable proportion of the output is made and sold by co-ops and negociants, but the top producers make world-class wines.

A little more than 20 percent of production is Riesling, making it the most planted variety, just, though some makers focus far more heavily on this grape.

Trimbach, for example, has 45 to 50 percent of its output from Riesling. Other grapes that flourish in Alsace include Gewürztraminer, Pinot Gris, Muscat, Sylvaner, and a mix of other lesser white varieties.

Pinot Noir is the only red, though it does not scale the heights here one finds in other regions. Alsace often represents excellent value (the Clos Sainte Hune is far and away the most expensive wine from this region – for $50 or less one can access a wide range of terrific wines. Alsace is a region that excels in food-friendly white wines.

The wines are usually dry, though there are numerous late-harvest efforts – vendange tardive and selection de grains nobles – which can be seriously exciting.

Trimbach vineyards in Alsace, France

Trimbach is among the elite producers of the region, and it tends to focus on drier styles. For me, Zind-Humbrecht, Domaine Weinbach, Hugel, and Trimbach make up a quartet representing the very best from this region. Schlumberger, Josmeyer, Mure, Marcel Deiss, and numerous others are also first-class makers.

There can be serious variation between producers when it comes to style of wines. At one end, Zind-Humbrecht offers wines of power and richness. Trimbach, on the other hand, is the epitome of racy, delicate, elegant wines. If I had to use one word to describe its wines, it would be “fineness.” The family has stated, “We are Protestants. Our wines have the Protestant style – vigor, firmness, a beautiful acidity, lovely freshness. Purity and cleanness, that’s Trimbach.”

Trimbach dates to 1626

Trimbach has been around for quite a while. Established in 1626, it owns around 40 hectares spanning more than 50 parcels and six villages (or 45 hectares across eight different villages or possibly 27 or 58 hectares – like so often happens researching these things, sources provide varying information; plus, not pointing fingers, certain wineries really should update their websites more than once a decade – I have seen all figures quoted).

It is now in the hands of the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth generations: eleventh generation, Hubert Trimbach, with nephews, Pierre and Jean, and Pierre’s daughter, Anne. Julien’s son, Jean, has also joined them.

Much of the fame of this family operation is considered to date back to Frédéric Emile Trimbach (indeed, the company’s full name is F. E. Trimbach after Frédéric). In 1898, he entered his wines in an international competition in Brussels and swept all before him. They have never looked back.

Frédéric moved the business from Hunawihr to Ribeauvillé (we are talking impossibly cute and colorful towns – think storks nesting on rooves – which really is a wonderful region to visit).

The family named one of its great Rieslings after him, “Cuvée Frédéric Emile,” first made in 1967. Some have argued that it is the second-best wine made in Alsace, after Trimbach’s Clos Sainte Hune, but to be honest it inevitably falls into the shadow of that great wine. At a fraction of the cost, however, it represents great value.

As with Clos Sainte Hune, even though the Cuvée Frédéric Emile comes from Grand Cru vineyards in Geisberg and Osterberg, there is no mention of vineyards – or even Grand Cru. To use “Grand Cru” the winery needs to name the vineyard/s, and Trimbach prefers not to do so. It has relented with two new wines, both Riesling – the Grand Cru Geisberg and the Grand Cru Schlossberg.

After hand-harvesting the grapes, some of these wines will spend lengthy periods maturing in the Trimbach cellars – at least six years for Clos Sainte Hune. A high percentage of the wines are exported.

The undoubted jewel in the crown, as you might have gathered, is Clos Sainte Hune. This is a small walled vineyard near Hunawihr, in the Grand Cru of Rosacker. It has been in the family for more than two centuries. Quite simply, this is the greatest expression of dry Riesling on the planet.

The vineyard is small at 1.67 hectares (other sources suggest even smaller, down to 1.4 hectares). It is south and southeast facing with the vines having an average age around 50 to 60 plus years. There is a limestone subsoil. With some age, the typical “refined minerality” of the terroir comes through. The wine can age for many decades.

Clos Sainte Hune does not see any oak and it also avoids malolactic fermentation. Average production is a miserable 8,000 to 9,000 bottles – for the entire world. The Trimbach family aims to harvest as late as possible “in order to achieve maximum ripeness, which, in turn, gives optimum depth of flavor and complexity.” I’ll confess I was a little surprised by this as the wines can be so refined, offering such finesse. The first time the wine was offered as Clos Sainte Hune, despite being in the family for at least a century at that stage, was with the 1919 vintage.

The outlier: Trimbach Clos Sainte Hune 1989

Over the years, this wine has popped up at numerous tastings. Bizarrely, I have many more notes for the 1989 than for any other vintage (2012 seems to have been popular as well). I’ll confess, even though it is very different to every other Clos Sainte Hune, it is my favorite.

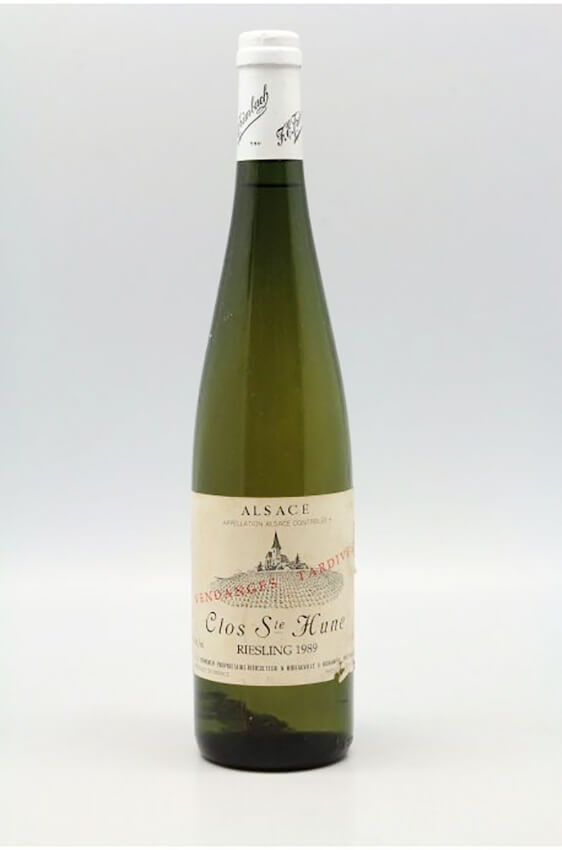

Trimbach Riesling Clos Sainte Hune 1989

The 1989 is perhaps the anti-Clos Sainte Hune. As I have mentioned, Clos Sainte Hune is a bone-dry style. There are suggestions that a few vintages are edging towards vendange tardive status but one, the 1989, is full-throttle VT, described as “Vendanges Tardives Hors Choix.”

I remember Hubert Trimbach telling me once that it was the only Clos Sainte Hune made in this style. The rest are dry. Most have around two to three grams/liter of residual sugar, below the threshold for detection by humans (alcohol sits 12 to 13 percent).

So why the 1989? A friend introduced me to it many years ago and it completely blew me away. Stunning wine, incredible length and balance, and even though sweet magically seamless. I have heard it described as “bottled fresh air,” so vibrant it is. My friend has been kind enough to open several over the years, each as good as the last.

Later, though many years ago, Hubert Trimbach was in town for a small dinner for local writers with a range of his current wines. I checked my notes: it took place 19 years ago last week. The evening included an amazing vertical tasting of the Frédéric Emile Rieslings, several vintages of Clos Sainte Hune, and much more.

Some things have changed a touch. The area of Clos Sainte Hune was given as 1.25 hectares with production at 6,000 to 7,000 bottles annually, which Hubert pointed out was less than the fabled Romanée-Conti vineyard. He was firmly of the belief that “dry was classical” and that Trimbach was “a guardian” of that style. Interestingly, Hubert was much more confident about the future of Trimbach than of Alsace itself.

I remember the evening as I had mentioned to my friend that I was attending the dinner, knowing that as a fan of the wines he’d be interested. When Hubert spoke to us at the start of the evening, he was a bit puzzled. He listed all the extraordinary wines that awaited us but then said that there was also a bottle of 1989 Clos Sainte Hune, but it was nothing to do with him?

I said, “Well, that will be Gerry.” I had to explain that Gerry, after I mentioned this to him, thought we should have the chance to look at the ’89 as he knew how much I loved it. It didn’t occur to Gerry to check, just that it was the sort of thing that would appeal. He was right, of course, and it was an extremely generous gesture, especially as there was never any chance he could join us due to prior commitments.

I asked Hubert why tinker with such a successful wine and move from dry to VT, even if just for a vintage. I recall him telling me that it was because that vintage saw an influx of botrytis through the vineyards at a far faster rate than they expected. Caught unawares, he and his team were left with no choice. Nature made the decision for them.

Later, a different friend was selling a large chunk of his excellent cellar, including a couple of six packs of the 1989. Sadly, he wanted silly money for it and we all had to decline. Instead, he shipped it off to auction where we managed to get it for less than half what he wanted (at least he has been able to share in a few of his former wines). So it has often appeared at our tastings.

I believe that Trimbach also attempted a “standard” in 1989, though to deem any vintage of Clos Sainte Hune “standard” seems appallingly insulting given the quality across the board. The “standard” was made from grapes picked two weeks before those infected by the botrytis. I have not seen that wine.

Trimbach wines

Tasting notes on some Trimbach Clos Sainte Hune vintages

Here are my most recent brief notes on some of the vintages.

1978: Tasted a couple of years ago, it had held up remarkably well. Nuts, citrus, stone fruit. Not the length of the best and possibly a touch of oxidation creeping in. 89.

1982: Some richness and interest here but it would appear its best days are behind it. 86.

1987: The last time I saw this wine, a few years ago now, it had the classic minerally background. Excellent balance and length. There were immediate notes of Riesling’s classic kerosene character (“kero” or “petroleum” is a character one may see in certain Rieselings; some love it while others are less enamored). It certainly would be a drink-up proposition these days and I have seen a few too many bottles suffering oxidation. 92.

1989 Vendanges Tardives Hors Choix: Lemons and mandarins. Wonderful balance, great concentration, incredible length, and seriously complex. Marzipan notes, honeycomb. It would surely be the ultimate foie gras wine. 98-99. Good bottles today drink as well as ever, but it is perhaps become a riskier choice unless you are certain of immaculate cellaring.

2008: Bone dry with attractive jasmine, floral notes. Great length and intensity with hints of lime and ginger. Stunning wine. As with all the good examples of Clos Sainte Hune, the texture is amazing – wonderfully supple and alluring. 97.

2012: An utterly glorious wine. Minerals and that slight hint of petroleum. Incredibly supple texture and truly astonishing length. Dry Riesling simply does not get better than this. 99. (We compared this to the Trimbach Grand Cru Geisberg, which drank well, but for me was not in the same class.) On another occasion, it was showing more lemony characters and I had marked it a point or two lower. In any event, an absolutely entrancing wine.

The next release will be the 2016 in October 2020 (those fortunate to have tasted it already are raving about how good it is). It will precede the 2015, which is being held back to give it more time in the cellar. This is something Trimbach’s people are not shy about doing, if they feel the vintage warrants it.

Sensational Trimbach Clos Sainte Hune, the world’s best dry Riesling, should be on every wine lover’s bucket list.

For more information, please visit www.trimbach.fr/all-about-clos-sainte-hune.

You may also enjoy:

Sparkling Wine From Tasmania: Not Yet Champagne Level, But Very Close

Château d’Yquem: Paired Years Elevate The World’s Best White Wine For A Simply Magical Experience

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

“As a very broad rule of thumb, German Riesling is sweet through varying levels; […]” …I feel you are endorsing a stereotype. Actually far less than 50% of German rieslings is sweet. Walk into any winery in Rheingau, Rheinhessen, Nahe or Pfalz and they will offer you dry rieslings to taste. I’d reckon your statement could apply for Mosel or maybe Mittelrhein. Even though also there you’ll find a fantastic range of dry rieslings.

This is not to disqualify sweetness in wine – which in Rieslings can be fantastic. But the equation German Riesling = Sweet is extremely dated.

Jerome, thanks for the comment.

That German Riesling is sweet is a very broad generalization, which is what I was trying to convey with “very broad rule of thumb.”

Fully agree there are some wonderful dry German Rieslings. Donnhoff is one of my all time favorite producers and does some amazing dry Riesling. Dr. Loosen, Heymann-Loweinstein, Muller Catoir, Georges Breuer, and plenty of others. But I do think that the “general perception” is still very much that Germans tend to the sweeter.