by GaryG

Once upon a time, my wife got married – but not to me. Everyone makes mistakes, right? She and her “starter husband” honeymooned in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and while the marriage didn’t last her love for all things Santa Fe certainly did.

Meanwhile, many miles away I was developing a deep appreciation for the niche art that is opera. Shortly after the future DrMrsG and I met 19 years ago, we combined our shared interests for a trip to Santa Fe Opera’s summer festival, during which, among other things, I immersed myself for the first time in the world of Native American arts. And came away with the purchase of a relatively modest Zuni sun-face bolo tie by Benjamin Tzuni, Jr.

The slippery slope begins: sun-face bolo by Benjamin Tzuni, Jr.

I trust that those of you who share the collecting bug see where this is going – no, not the part about how I eventually got the girl, although that was great, but the start of a journey of learning about Native American arts and the artists behind them while amassing a set of treasured items that now stretches well beyond what I would have predicted.

That good old watch collecting taxonomy, reapplied

As I’ve been thinking about it, while I haven’t been consciously applying my pal Terry’s watch-related collecting model to Native American art (and specifically in this case to my jewelry items), the idea of foundational, fun, and patronage items within a collection still applies.

For all of the items bought new from living artists the patronage concept applies (although I’ll come back to a caveat on this later). As for the rest, there’s a good mix of fairly important works and “just because” emotion-driven buys in the set.

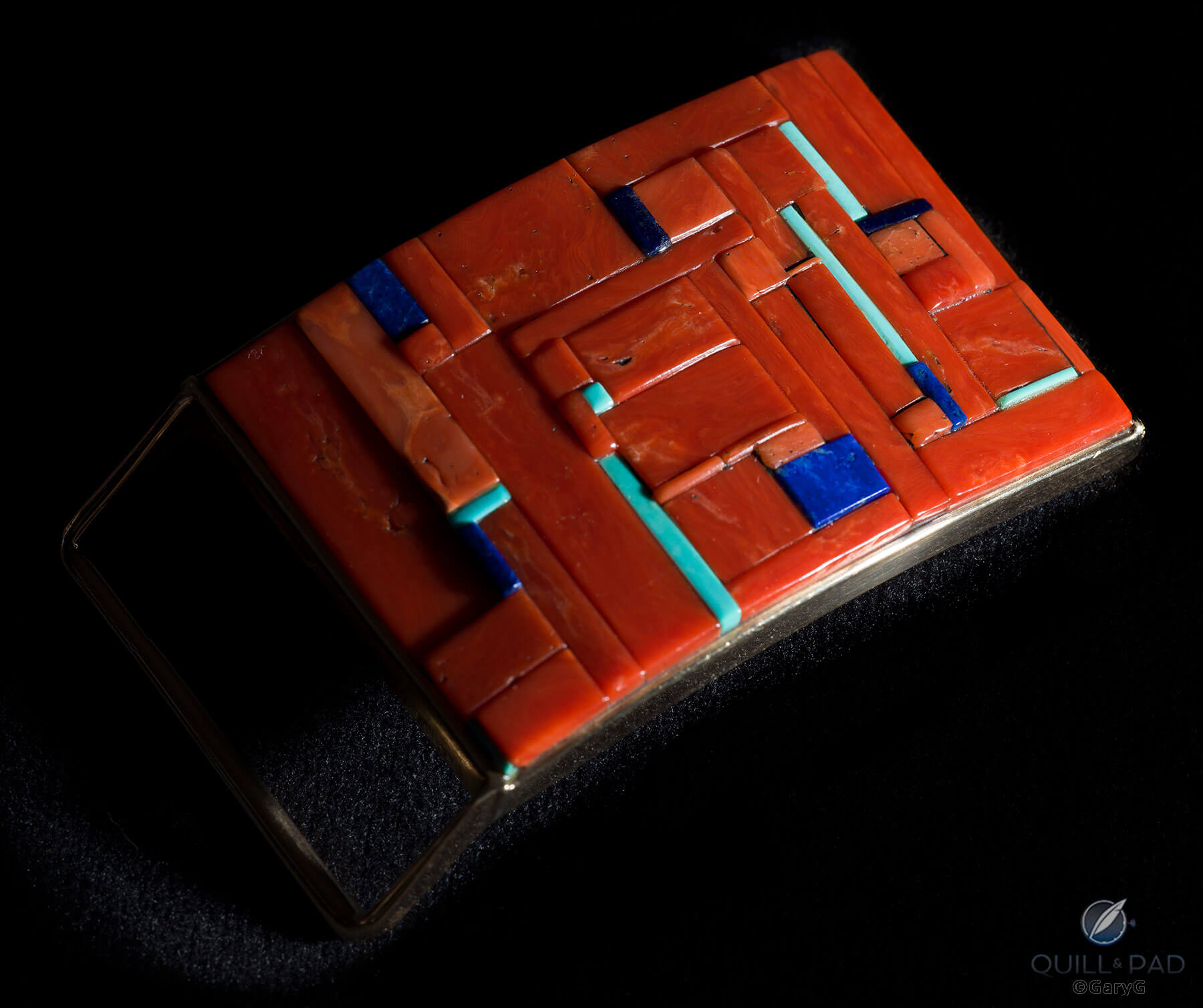

Definitely foundational: coral, turquoise, and lapis lazuli buckle by Charles Loloma

At the top of the “foundational” list are two items by Hopi legend Charles Loloma (1921-1991), bought, like many of the items I show here, through my trusted friends Jed and Samantha at Shiprock Santa Fe.

Born near Hotevilla, Arizona, Loloma began his career as a muralist and architectural illustrator before moving on first to pottery and finally to a celebrated career as a jeweler. At first, Loloma’s style incorporating some non-Native American influences was harshly received in some circles as “not Indian enough,” and his work was rejected from the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial three times before finally finding acceptance.

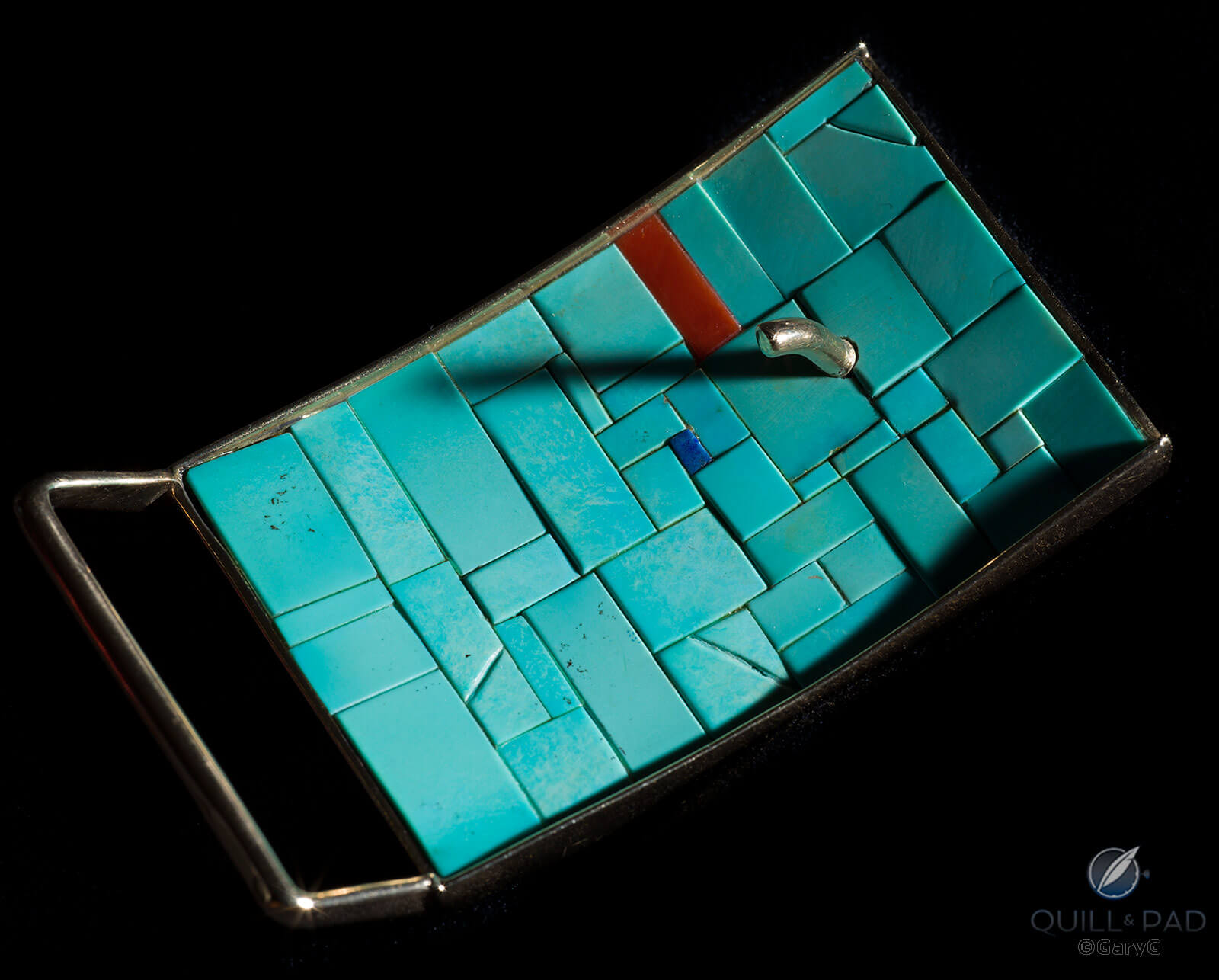

Today, Loloma’s pieces are seen as masterworks; I am very fortunate to have two of his buckles, including the coral-based one pictured above, whose interior reveals a second full stone mosaic in turquoise.

Interior view, gold and coral Charles Loloma buckle

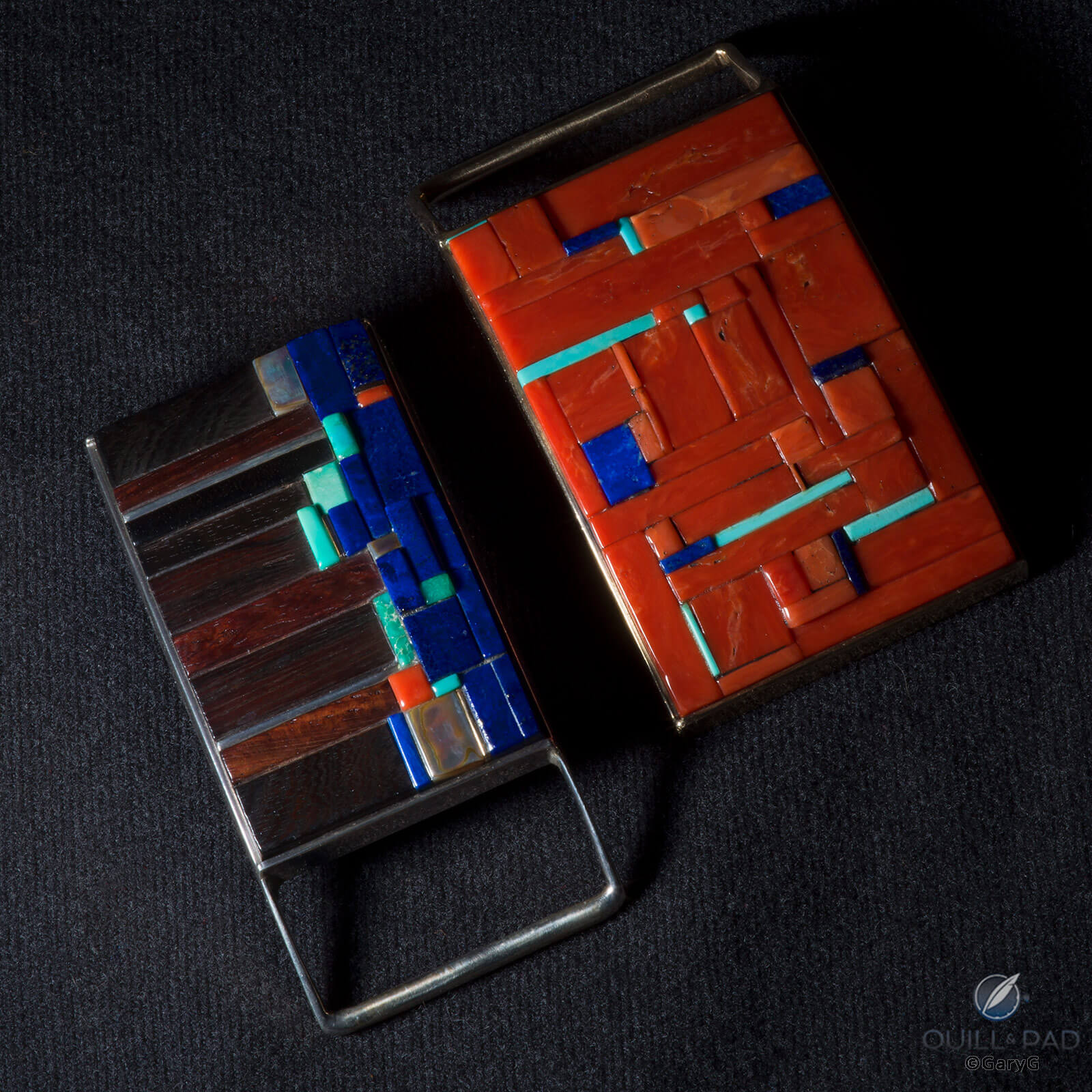

My second Loloma piece, shown below next to the first, displays Loloma’s interest in unconventional materials: ironwood predominates along with abalone shell and accents in the more traditional turquoise, coral, and lapis lazuli.

While the gold and coral buckle is definitely a special occasion item, the wood-and-blue look of the silver buckle makes it an easy wearer with jeans, even if it does cause a fair number of double takes on the sidewalk during our visits to Santa Fe.

Two belt buckles by Hopi artist Charles Loloma

Protégés and influences

To understand the story of Loloma, it’s important to include two other figures: Eveli Sabatie and Verma Nequatewa (aka Sonwai), both of whom worked very closely with Loloma and both contributing to and learning from his artistry.

Nequatewa (Hopi, born 1946 and still active today) is Loloma’s niece and participated in making many of the works of the Loloma studio in the 1970s and ’80s before carrying on with her own creations, many of which utilize design features such as the “profile” look associated with Loloma but go beyond them and incorporate her own more feminine style.

I’d wanted one of Nequatewa’s pieces for several years when I spied a men’s-sized gold profile ring in the case and swore that if I could get it on to my finger, I’d buy it! You can see it at right in the image below.

Eveli Sabatie bolo (left) and profile ring by Verma Nequatewa/Sonwai

Sabatie was born in 1940 of European parents in Algeria, raised in Morocco, educated in Paris and Berlin, and ultimately moved to San Francisco where she became involved in Native American causes. On a subsequent visit to Hopi at the invitation of a traditional tribal leader, Sabatie famously met – and was charmed by – Loloma in a laundromat and began working in his studio before eventually branching off on her own.

In the photo above, you can see in the bolo at left the hallmarks of Sabatie’s style: a fusion of African and Native American motifs along with creative mosaics and the use of multiple materials.

Unlike both Loloma and Sonwai, however, Sabatie famously avoided repetition in her jewelry. So while an “Eveli” piece is often easily identified by its overall look, the multiple subtle variations on a theme such as in Sonwai’s profile rings and bracelets aren’t in evidence in Sabatie’s body of work.

Lapidary wizardry: Richard Chavez

Just as classic watchmaking doesn’t begin and end with George Daniels and his disciples Roger Smith and F.P. Journe, there are many foundational Native American artists beyond the Loloma sphere.

One long-time leader is San Felipe Pueblo artist Richard Chavez (born 1949, still active), who focuses on the lapidary aspects of jewelry creation using the best available materials and flawless cutting, polishing, and setting, all within a recognizable visual style.

Four pieces by Pueblo artist Richard Chavez

In the photo above, from bottom right:

- Silver buckle inlaid with turquoise, coral, and black and white jade – my first Chavez piece and primarily worn with dark suits.

- Gold bolo with fossilized ivory, coral, and black jade – a stunner with a cream dinner jacket on Santa Fe Opera evenings.

- Silver bolo with black jade, turquoise, and coral – this one is actually DrMrsG’s, bought several years before we met.

- My most recent Christmas gift, an early and unusually shaped Chavez ring with highly polished wood, shell, black jade, and turquoise inlay.

Even from a distinguished artist like Chavez, a small ring is very much a “fun” item that can be worn around town without worry, yet never fails to hold my eye for several seconds whenever I look at my right hand.

Gibson Nez, master of stamping

Stamped silver buckles, bracelets, and bolos are perhaps more along the lines of what many would consider “traditional” Native American work, and within this category of jewelry I haven’t found any creator whose work interests me as much as Gibson Nez (Jicarilla Apache/Navajo, 1947-2007), a one-time rodeo champion whose work in thick metal with varied geometries, razor-sharp lines, and prominently showcased stones is instantly recognizable.

Two bolos and a buckle by Gibson Nez

I really need to wear my bolos more often, as among other things it would allow me to enjoy the beautiful sugilite at the center of the bolo below left in the image above on a regular basis.

Happily, I do wear the lapis lazuli buckle – frequently and with great pleasure.

Speaking of bolos . . .

I do love bolos! Starting with that one Zuni piece that began it all, it seems that my current count of these distinctive ties has somehow expanded to 14 while I was looking in the other direction.

Mask-based bolo ties by Hopis Phillip Sekaquaptewa (left) and Roy Talahaftewa

I love them in all sizes and shapes, with and without stones, including a couple of quite large Hopi mask-based bolos shown above that feel great around the neck and rarely fail to start a conversation.

Bolo and buckle by Diné (Navajo) artist Victor P. Beck, Sr.

On the slightly more elegant end, there are the slim creations of Victor Beck with their characteristic fins, and on the more ornate side the silver-and-gold creations of Navajo artist (and movie stuntman) Arland Ben that showcase noteworthy mineral examples like in the piece seen below.

Bolo tie by Navajo Arland Ben

Where there are bolos, of course, there are tips! Whether they are simple or ornate, geometric, or representing flowers or other natural objects, they are an important part of the art. I’ll confess that I’ve spent more than a few long moments deep during the second or third act of a long-ish opera contemplating my bolo tips rather than being riveted to the third refrain of some chorus or another.

Bolo tips (from left) by Arland Ben, Gibson Nez, Roy Talahaftewa, and Eveli Sabatie

And then there were cufflinks

Remember cufflinks? Remember cuffs? Those things on what we called “dress shirts” that we wore with . . . oh, never mind.

I do hope that it’s not too long before I’m pulling out at least a few shirts that lend themselves to the use of cufflinks. And when I do I’ll have several pairs of nice Native links to choose among, including the ones pictured below by Victoria Benally and (at center) Verma Nequatewa/Sonwai.

Three sets of Native American cufflinks by Verma Nequatewa/Sonwai (center) and Victoria Benally

Native American jewelry . . . and watches

Another part of the fun is matching up rings, buckles, cufflinks, and bolos with watches. While I’m no slave to fashion or convention when it comes to picking what works with what, it is enjoyable to give a bit of thought to coordination as I choose my accessories for a particular occasion.

When I first saw the new Stella-inspired Rolex Oyster Perpetual watches, one very clear reason that I was drawn to the turquoise blue-dialed piece was the opportunity to match it up with some of my Native items, including a frequent daily wearer, a beautifully made rectangular silver and turquoise ring by Santo Domingo (Kewa) Pueblo artist Julian Lovato (1922-2018).

And my raft of dark blue dials do a great job of matching up with the lapis lazuli prevalent in so many Native American designs.

Matching up: Julian Lovato ring with Rolex Oyster Perpetual 41 Turquoise Blue

Food for thought: appreciation or appropriation?

A few weeks ago, I posted the photo shown below – my wood-and-lapis-lazuli Loloma buckle and A. Lange & Söhne Odysseus – on my Instagram page as part of the theme of matching up Native American jewelry and watches.

I’ll confess that I was taken considerably aback by the response from one viewer, a self-professed Native activist who made it clear in no uncertain terms that he considered my display of this item – and in fact, my ownership of it – to be an affront to Native Americans and the perpetuation of white Americans’ exploitation of his people.

A. Lange & Söhne Odysseus in steel with Charles Loloma silver belt buckle

I will be the first to confess that when it comes to appreciating and collecting works of Native American art, I could be much more knowledgeable about the artists as well as the religious and cultural symbolism embedded in the works themselves.

That said, I’ve never made it past Chapter 2 of George Daniels’ book Watchmaking so I’m perhaps similarly shallow about the mechanical details of timepieces.

But I do understand that with Native American art we are treading on more sensitive ground, and that the record of treatment of Native populations in our country over the years has frankly been shameful. As a result, the gentleman’s comments did make me ponder at length: is the third leg of my collecting here really patronage or something less worthy despite what I see as positive intentions on my part?

I’d welcome thoughts from our readers in the Comments section below and by private communication at any time, but my basic conclusion is that these works were created as goods for commerce, not as religious or cultural icons, and should therefore be treated as such.

When it comes to newly-made Native products, I (like many others) make it a practice to attend Native-organized shows and markets to buy directly from the makers, and I also buy from the artists’ authorized dealers. So while artists were very likely exploited in the past, mechanisms now exist to ensure fair dealing.

As for vintage pieces like the fossilized ivory bolo by Navajo artist Charles Willie in the final image below, I think that respectful and careful ownership helps to preserve the legacy of the craftspeople who made these objects – and I’m looking forward to taking the opportunity to learn more about them, their lives, and their societies.

Parting shot: shield-shaped fossilized ivory, coral, and lapis lazuli bolo by Charles Willie

To order Visions of Sonwai about Verma Nequatewa and her work, please visit www.sonwai.com/contact.

To order the book Loloma: Beauty is His Name from the Wheelright Museum of the American Indian, please visit www.wheelwright.org/product/loloma-beauty-is-his-name.

You may also enjoy:

How The Native American Ancestral Puebloans Kept Track Of Time

Why I Bought It: Rolex Stella-Inspired Oyster Perpetual 41 With Turquoise Blue Dial

GaryG Goes To Paris To Pick Up Custom Boucheron Cufflinks Or How I Spent My Summer Vacation

Detailed Primer On Gemstones And Their Appreciation: An Introduction To The Finer Things

Cartier’s Cufflinks And Watches: Sophistication With A Nicely Personal Touch

Beauregard Dahlia And Lili: Opening Like A Flower

Breguet Cammea Watches Harness The Delicate Art Of Cameo Shell Carving

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Just beautiful pieces! I have a small number of very fine Native American buckles that I wear often and admire the exquisite craftsmanship in each piece. Thanks for sharing these.

Thanks, Steve! These buckles are so wearable and as you say always give an opportunity to admire the craftsmanship behind them. Glad you are enjoying your so much!

Best, Gary

Gary, thank you for taking the time to showcase some of your Indian wardrobe accessories.

The self-described “Official Indian Critic” has no moral legitimacy or right to complain about your jewelry – you are free to purchase and wear what is freely sold to you on the open market. Imagine the outrage if White Americans were to tell all Indian’s in North America “Sorry, Thomas Edison’s electricity is not allowed on tribal reservations in order to keep you pure and untainted by White Western Technology. Learn to build a fire again….”

Thanks for your comments, Mike — I do my best to be sensitive to folks’ feelings, but I will confess that I’m not a big fan of the offense taken on the topic of appropriation. Besides, it’s a practical matter for me — I don’t think I could live without pizza and quesadillas !

Best, Gary

Thanks for leading an enjoyable excursion into a world of artistry new to me. Bolo tips seem foundational elements akin to the lugs of a wristwatch… either of those supporting parts can sink the main show.

BUT, what really got my attention in your piece was the imposition of the Native activist’s opinions upon your appreciation of merging artisanal efforts across cultures. Isn’t an intention of artists the expression of some sort of emotion in their work, which then serves as tableaux for their patrons’ imagination? We all suffer when politics smother our imaginations.

Thanks, Peter — and I like your analogy between bolo tips and watch lugs quite a bit.

I suppose that I’m not immune from causing inadvertent offense, but in this case I tend to agree with you that the anger shown toward an honest effort at appreciation was misplaced.

Best, Gary

I live in Arizona and have a small group of bolo ties, belt buckles and cufflink sets. The historic focus of the work was to cater to tourists and was promoted by intermediaries like the Fred Harvey Company which was a large dealer at stores and company hotels throughout Arizona and New Mexico. I generally buy from a small group of dealers who have had long term direct connections with the artists. Charles Loloma was probably the Benvenuto Cellini of contemporary Native American jewelry craftsman but I am partial to Victor Beck. The bolo tie was once a staple in Arizona but they are seen less and less. It is often said that watches are the only jewelry men wear but the Native American pieces in your collection are delightful exceptions to that so called rule.

Thanks for the interesting historical context, Howard. I’ve done most of my buying from a favorite dealer in Santa Fe who is a fifth-generation descendant of trading post owners, and have had the opportunity to meet several artists at that store as well as directly at events including Indian Market and Spanish Market.

My wife has a Victor Beck bracelet that has a very different look from his signature fins — we are both big fans of his, as you can tell.

I do enjoy wearing these pieces! I get the occasional side glance when wearing a bolo but it’s part of how I like to express my tastes.

Best, Gary

I have always loved Native American pieces

My ex husband and I traveled often to Santa Fe since we lived in Scottsdale,AZ

I also have beautiful pieces that were purchased at The Heard Museum/Phoenix

I cherish every piece I have!!

Hi Deborah — congratulations on what sounds like a lovely collection! I appreciate your commenting here and hope that you continue to enjoy your pieces.

Best, Gary

I am a visual artist. When somebody buys one of my paintings they invest and support me and my work, for that I am grateful. I fail to see how, if you buy from a legit master of a craft, you’re disrespecting the creator and/or the creation. If anything you are, in all sense of the word, putting your money where your mouth is and investing in the perpetuation of a given craft.