In this day and age it is so hard to imagine a lone watchmaker sitting hunched over a bench filing and sawing as if his life depended on it. This is an era where even the highest end watches are now made with the help of computer-controlled machines, and that is an image that is hard to unglue from one’s mind when it comes to manufacturing practices.

However, the independent watchmaker is a very good example of how to combine the best of both worlds.

And, really, it’s not only his life, or at least livelihood, that depends on it, but also the uniqueness of the timepiece that will emerge.

Making a watch by hand in today’s fast-paced, relatively industrialized watch industry may not be the usual or most efficient production method, but it is the generally the method used by watchmakers who are members of the A.H.C.I., a group of independent creators founded in 1985 on the premise of building strength in numbers.

The A.H.C.I., short for Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendents (Horological Academy of Independent Creators), is a loose grouping of 34 idealistic independent watchmakers and five candidates, currently hailing from 15 different countries around the world.

The multiplicity of independent watchmaking

The chosen path of these individualistic inventor watchmakers – and to qualify for membership in this select group a watchmaker has to both invent and manufacture a new movement or complication – is indeed anachronistic. And although the products that emerge may not always be everyone’s cup of tea, they do attract the attention of collectors of rare taste who follow not only the horological escapades of these extraordinary men (currently there are no female members or candidates, which is a shame) of varying age and nationality, but also the passion and personality that goes into each extremely limited timepiece.

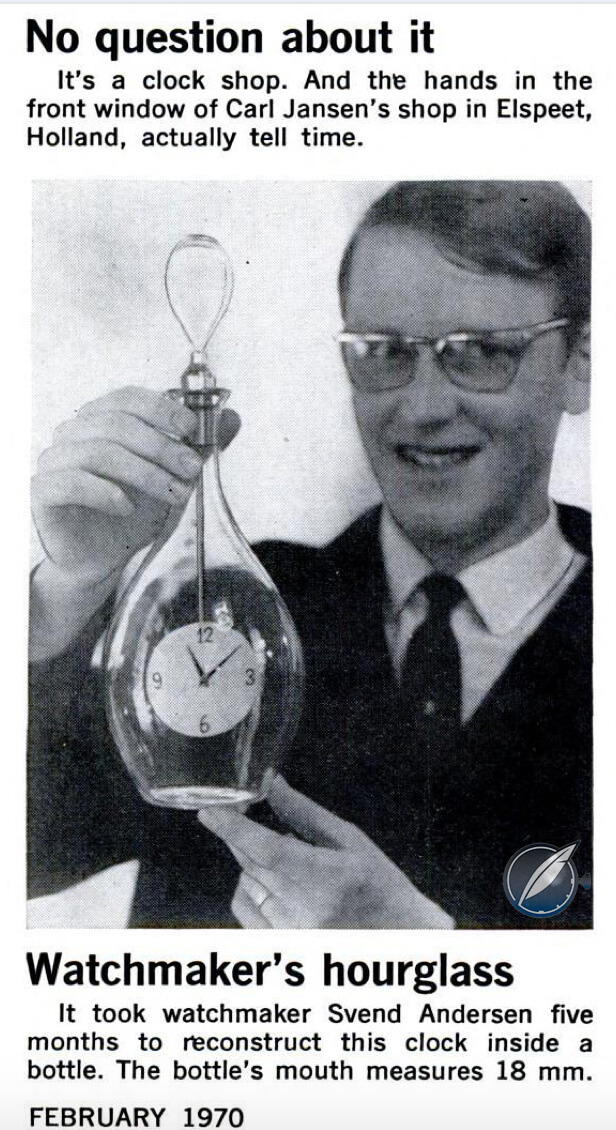

Neither of the founders of this extremely interesting organization are Swiss nationals. Svend Andersen hails from Denmark, while Vincent Calabrese is Italian. However, both live and work in Switzerland – and have done so for decades. Andersen, in fact, has been a resident of Geneva since 1963.

Several years ago, Andersen, who was born in 1942 in Baekken, Denmark, took some time to briefly explain the history of the A.H.C.I. from his perspective, which in great part also explains his own history in this field.

In the wake of the quartz crisis of the 1970s and early ’80s, the mechanical watch had all but died out. However, there were still a few master watchmakers and creators who firmly believed in what they were doing and persevered. Two of these were Andersen and Calabrese, both living and practicing their craft in Geneva and Lausanne respectively.

Andersen had achieved a certain amount of fame by creating the seemingly impossible: a clock in a bottle, which took him five months to reconstruct. He actually assembled and regulated a small clock through the mouth of a glass bottle measuring just 18 mm (3/4″).

This feat was noticed in the watch community, and it earned Andersen a stint in Patek Philippe’s complications workshop after leaving Gübelin, where he had worked for five years.

He left because his employers were not happy that he had been inventing alongside his work. However, the bottle clock earned him the nickname “watchmaker of the impossible.”

Andersen related that at the end of the 1970s, working as a restorer, “someone brought me a very complicated movement with no case and asked me to reconstruct it.” Upon achieving this difficult task, he was assaulted with an avalanche of requests from collectors regarding vintage pieces they owned.

He then described how, by about 1984, he and his friend Calabrese were being visited mainly by Italian collectors for bespoke mechanical watches.

“Around this same time, we also discovered that financial investment groups were beginning to buy up old factories and brand names from the watch industry,” he said. “And all of a sudden, new manufacturers were coming to us for new creations in mechanical watches.”

Andersen and Calabrese knew this was the time to act and to attract interest in independent mechanical watchmaking. History has since shown that their decision was perfectly timed: the founding of the A.H.C.I. remains a key focal point in the fine watchmaking arena, and may well have been one of the proponents for the renaissance of the mechanical watch at the time.

Andersen has described the artists in the loose group as “individualists who make exceptional watches” – though the latter term may well be a mistranslation, for many of the creative artists that make up the Academy, as it is known, do not make the more marketable wristwatches, but rather clocks. Yet another anachronism.

Andersen’s key watches

Our own Ian Skellern pointed out in his 2010 book The Hands of Time, which was published for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the A.H.C.I., that few of Andersen’s watches are very well-known because, as Andersen told him at the time, “90 percent of my inspiration comes from people asking if something is possible. I never say no, I will always think about it.”

Despite making more than 100 one-off custom timepieces over the course of his career, Andersen has become particularly known for a few different models of his that do appear in small series – such as the erotic watch, the first of which he made in 1997. Since that year, his carefully constructed automatons have been located in beautiful cases topped off with a classic dial that never lets on what the back of the watch could reveal: a beautifully painted love scene with real moving “parts.”

Commemorating a decade of his erotic watches, Andersen introduced the Eros 69 in 2007, a work inspired by Chinese erotic silk art of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. At that point, he created a new case for his repeating timepieces boasting a reversible central body and a static frame.

A device at the crown allows the wearer to lock, unlock, and turn the central body so that the repeating love scene can be seen instead of the time against the backdrop of a painting of a fully clothed Chinese couple.

The automata figures consist of individually cut and painted components for an enjoyably realistic effect, also making each timepiece unique. Andersen used a highly modified and rare vintage Langendorf alarm ébauche that can be manually wound in both directions as the movement powering his erotic art.

The Montre à Tact arrived in 1998. Here the time indication is optional on the dial, but can be discreetly seen in a window between the strap lugs. Just how difficult this apparently simple task is can only be appreciated by a glance at the complicated movement.

The display drum surrounding the movement made winding by crown impossible, which is why Andersen decided to simply move the winding mechanism to the back of the case.

Calendar watches

Andersen is without doubt best known for his calendar watches: the 1884 world time watch, the model that has now become the Tempus Terrae based on the world time patent by Louis Cottier, and the Perpetual Secular Calendar.

In 1989 Andersen created his first world time watch and christened it Communication. This was followed by the subscription series Communication 24 (Henrik, Prince Consort of Denmark, wears number one).

Also in 1989 Andersen created the world’s smallest calendar watch, a timepiece that was entered into the Guinness Book of World Records that year; 1993 saw the advent of Andersen’s Perpetual 2000 – “the only readable perpetual calendar on the market,” he said at the time.

In 2003, the Dane introduced a watch in homage to the standardized world time created by Sir Sandford Fleming in 1884. Appropriately, Andersen named his masterpiece 1884, dedicating the gold rotor to Fleming and including his name, years of birth and death, bust, and the words “inventor of world time.”

The Svend Andersen 1884 is a worldtimer commemorating Sir Sandford Fleming, who introduced standardized world time zones in 1884

At Baselworld 2015, Andersen paid homage to 25 years of the worldtimer he created in commemoration of Louis Cottier’s original 1950s patent with his new Tempus Terrae, a world time timepiece with two crowns and his signature blue gold (a patented 21-karat gold alloy that turns blue when heated) in the center of the dial as well as on the rotor.

The owner can choose what pattern the blue gold dial should have: guilloche by hand, a tapisserie, or a scale motif (seen above). As is his custom, Andersen allows, if not encourages, personal customization of this watch.

This was the fifth worldtimer he released in his long career.

Three very different watches from Svend Andersen as seen at the MIH in 2015: (l to r) 1884, Tempus Terrae, and Montre à Tact

Perpetual Secular Calendar

Andersen’s Perpetual Secular Calendar, created in 1996, boasts a complicated gear train crowned by a small pinion turning once every 400 years in order to take into account the suppression of the leap year required to bring our Gregorian calendar in line with the solar year.

Years exist within our calendar system that should by all rights be leap years, but are not because they are simply not required. These are called secular years and occur every time the first year of a century is not divisible by 400. Andersen’s Perpetual Secular Calendar takes these into account.

View through the display back of the Svend Andersen Perpetual Secular Calendar (photo courtesy www.kaplans.com)

Baselworld 2016 will herald a horological celebration of twenty years of the Secular Perpetual Calendar with an edition of 20 platinum watches boasting a hand-guilloché platinum and blue gold dial. The day and date as well as a “special day” will be visible on the front of the watch, while the back of the watch will display the secular calendar as usual.

And now?

Late in 2015 the news came through that Andersen had sold his company, a fact that we were able to confirm on running into him in the Carré des Horlogers during the 2016 SIHH.

“Yes, but it’s more a ‘transition’ than a sale,” Andersen, now 73, laughed as we enjoyed a toast to the independent watchmakers in the nine booths around us. “For me horology is not only a profession, it’s a passion. And it’s life.”

And right on cue, the new owner sitting next to him raised his glass and confirmed what his business partner was saying. “Svend’s not really retiring.”

The new owner is one Pierre-Alexandre Aeschlimann, who has officially been the president of Andersen Genève SA since March 2015. He is a self-proclaimed watch lover as well as being an engineer, consultant, and a Swiss businessman who has worked in finance.

His obvious enthusiasm for both horology and Andersen’s creations immediately put me at ease.

Pierre-Alexandre Aeschlimann (left), the new owner and CEO of Andersen Genève, sharing a glass with Svend Andersen at SIHH 2016

“It’s a question of human beings, but also a question of passion,” said Aeschlimann. And with that, all talk of laying down watchmaker tools ceased and we enjoyed the moment of friendship and camaraderie.

For more information, please visit www.andersen-geneve.ch and www.ahci.ch.

Quick Facts Tempus Terrae

Case: 39 x 9 mm, available in yellow gold, red gold, or white gold (shown), hunter-style case back

Movement: automatic vintage AS movement with in-house world time module

Dial: blue gold (21-karat gold mixed with a secret ingredient to turn blue when heated), guilloche by hand; fully customizable

Functions: hours, minutes; second time zone (24-hour display), world time

Limitation: 25 pieces each in 2N yellow gold, 5N red gold, and white gold

* This article was first published March 8, 2015 at Worldtimers, Erotic Watches, And Poker-Playing Dogs: A.H.C.I. Co-Founder Svend Andersen Has (Semi-) Retired, But His Brand Lives On.

You may also enjoy:

Andersen Genève Jour Et Nuit: From Its Beginning To The New Jumping Hours 40th Anniversary

Konstantin Chaykin And Svend Andersen Joker Automaton: Haute Horlogerie Irreverence (On Video)

Give Me Five! The AHCI Celebrates 30th Anniversary At Baselworld 2015

Marco Lang Zweigesicht-1: One Watch, Two Faces, And A New Shock-Tracking Indication

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!