Nigel Band is a professional diver with over 30 years’ worth of commercial and teaching experience under his belt.

Off to work, Rolex Sea-Dweller on wrist (photo courtesy Nigel Band)

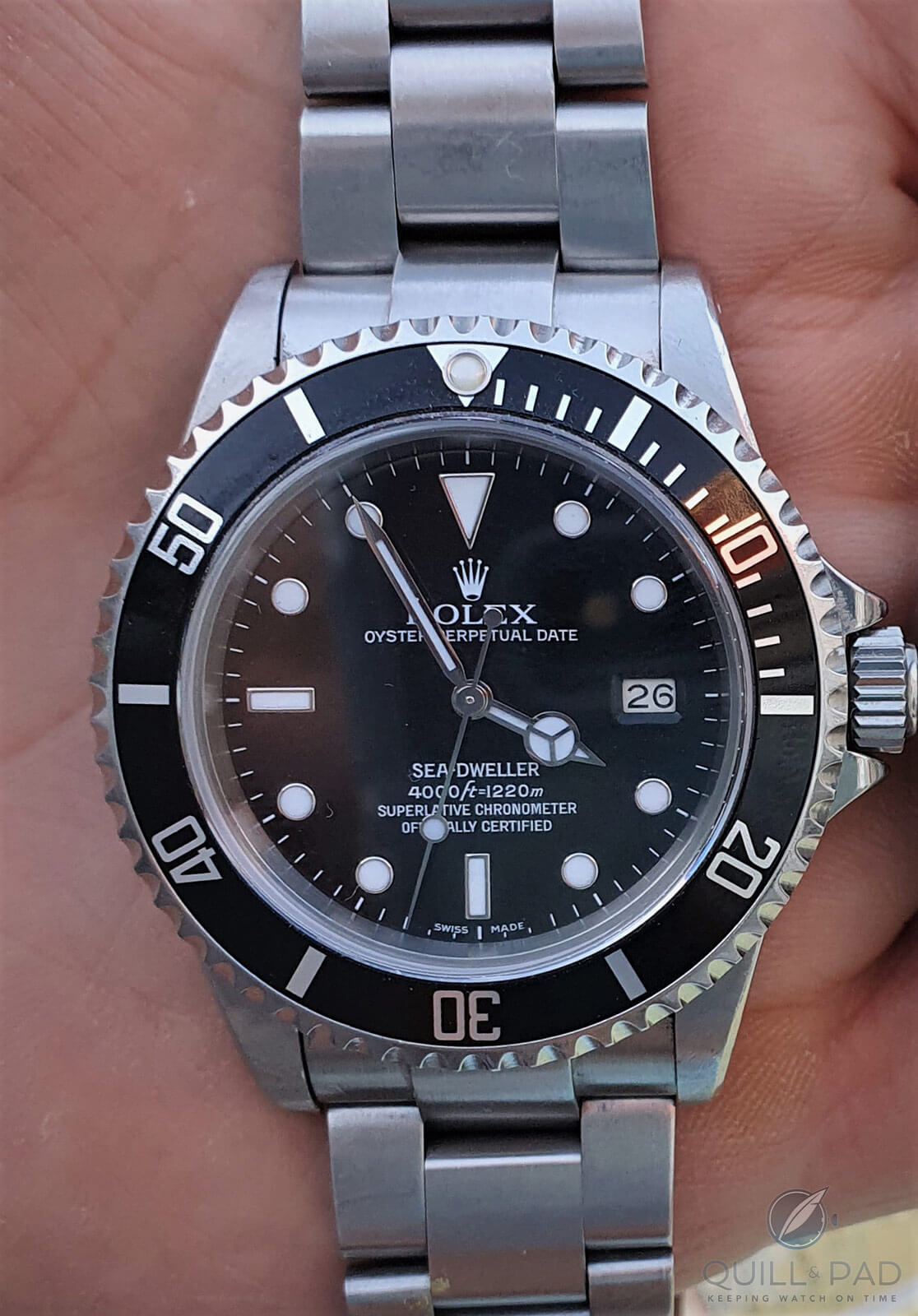

He also owns two rather unusual Rolex watches: the first is a 1986 “triple-six” Rolex Sea-Dweller Reference 16660. It is unusual in that it is about as far from a desk diver as you will get. Most dive watches only get wet in the kitchen sink or shower and come no closer to helium than balloons at a children’s birthday party. But Band’s Sea-Dweller has clocked up more than 20 years’ saturation diving to depths of 120 meters.

It’s the real thing.

The second is a 1952 Rolex Oyster Perpetual of considerable historical interest, which ventured to great altitudes. But I’ll get to that later.

As the son of an oil company executive, Band had an unusually peripatetic childhood, living in five countries by the age of 15, and has some rather entertaining stories to tell. I caught up with him for a Zoom interview last week, as is the current fashion, and he told me how he got into diving in the first place.

Diving as a career

“It was actually after an off-the-cuff remark that my father made at home in London. Once it had become clear that I probably wasn’t going to make it to university any time soon, after another heated family discussion along the lines of ‘what are we going to do with Nigel,’ as he left the room in despair my father said, ‘Well, you can always become a diver’.”

For an oilman like his father, this was tantamount to saying, “Well, you can always drive a taxi.” But even though he had no actual diving experience, it struck a chord with Band, who had always felt as much at home in the water as on dry land, if not more so.

As a boy in Oman, he recalls heading off to the beach to go snorkeling with pals after school each day rather than playing football as most kids do. And when Band’s father sat him down with his brother and sister to tell them that the family was moving to the UK, the children looked at each other in horror and burst into tears simultaneously. The offshore life held a strong appeal for him.

Band immediately applied for a diving course in Plymouth but was turned down because he was too young. He did however manage to wangle an apprenticeship on an oil services barge in the Far East, and his diving career was under way.

As a fresh-faced 18-year-old English public school (private school in the States) boy he didn’t fit the usual diver mold at all – his first colleagues were a battle-hardened crew of Americans, Australians, and New Zealanders – literally, as most of them were Vietnam veterans. For the first week he didn’t dare open his mouth.

1986 Rolex Sea-Dweller

Band came to his Sea-Dweller after a colleague returned offshore looking to make a quick sale of a Rolex watch after a longer-than-planned spell of unemployment. He figured he could afford the asking price, but was sternly told by his supervisor, “you’re too young for a Rolex, lad, you can get one when you’ve done your first saturation dive.”

For the time being he carried on wearing his Casio G-Shock – which was a popular choice for divers at the time, even if they had to keep a backup due to the watches’ tendency to explode on the way back to the surface – followed by a Seiko 150 Sport, a rugged quartz dive watch.

He eventually bought the Sea-Dweller for £680 at Schiphol airport in 1986 on his way home from an offshore project in the Middle East. The airport’s Rolex retailer must have been a little taken aback by the scruffy 23-year old sauntering in dressed in jeans, T-shirt, and flip-flops and asking to try on the Sea-Dwellers.

Nigel Band’s Rolex Sea-Dweller (photo courtesy Nigel Band)

Diving deeper

Saturation diving (“SAT”) was first experimented with in 1938 but took off in a big way with the growth of offshore drilling in the oil industry in the 1960s. Technically, it is very different from scuba diving with a compressed air tank. Saturation diving involves breathing a mixture of helium and oxygen (which “saturates” the body tissue); divers can live and work underwater at great depths for several weeks at a time, returning to the diving bell and pressurized accommodation after each shift. But they require a decompression period of up to several days once a tour has been completed to avoid decompression sickness. Unlike in scuba diving, the saturation diver wears a full helmet loaded with communication devices, lights, and cameras, all fed by an “umbilical” air line from the surface vessel.

Saturation divers are a rare breed as they require both physical stamina to carry out shifts of six to eight hours and then remain on site in cramped, pressurized accommodation for several weeks and the mental capacity to work on the sea bed or under a drilling platform in total darkness and/or zero visibility.

This work is not for the faint-hearted, and trained welders and fitters tempted by the prospect of doubling their earnings by “doing it underwater” often found that they simply don’t have what it takes. On one “zero-vis” job, Band recalls being “zapped” by electric rays as he felt his way along a pipeline back to the platform, much to the amusement of his surface colleagues whose laughter was clearly audible in his helmet earpiece.

But he took his revenge when a large sea snake followed him into the diving bell at the end of the shift. The snake became disoriented and aggressive on finding itself apparently on dry land, so Band decapitated it for his own protection. Then, when his diving bell docked, he tossed its still-writhing body to his horrified colleagues in the accommodation unit as an arrival gift.

SAT also requires a different type of diving watch as it also gets “saturated” or pressurized. The helium gas that accumulates inside the case during the dive is unable to escape at the same rate as the pressure is normalized on the ascent, resulting in the crystal blowing off. The Rolex Sea-Dweller is essentially a Submariner with a helium release valve.

Emerging into the diving bell after a shift (photo courtesy Nigel Band)

In Band’s case, the work consisted of “mainly nuts and bolts” – such as supervising the lowering of pipeline sections from the surface vessel and joining the flanges at the end of each piece together with bolts that can weigh up to 140 kg each. He only recently retired from “wet” diving operations and now applies his experience as a commercial dive planner and supervisor in the Middle East.

After a number of years saturation diving and spending long periods in pressurized accommodation, Band’s Sea-Dweller was looking somewhat the worse for wear and not keeping time as it should, so he sent it back to Rolex for a service, which included having the badly corroded hands replaced.

It is on this point that the difference between an authentic tool watch and a mere “desk diver” becomes clear. Companies like Rolex invest considerable time and money in developing diving watches to a rigorous set of industry specifications, in some cases laid down by the military or a defense ministry that governs timekeeping, water resistance under extreme pressure, and legibility. They are required to maintain those standards when a watch requires maintenance. Given that a defective or unreadable watch could endanger a diver’s life, they have little regard for the concerns of vintage watch collectors who swoon at the sight of a spider dial, faded bezel, or hands whose lume stopped glowing years ago.

Some years later, as a result of such repeated helium exposure, the bezel on Band’s Sea-Dweller had “ghosted” to a light grey to the point that the numbers were illegible, so the next service included a replacement bezel. The Sea-Dweller now looks remarkably fresh, and while he is aware that it would probably be worth a lot more in monetary terms if it still had all the original parts, that is not why he bought it.

“Watch conkers”

Readers of a sensitive nature should look away at this point, or jump to the next section, especially if they are into rare watch prototypes.

As commercial divers spend a lot of time sitting around waiting, either before going into action or in decompression after a deep saturation dive, they inevitably look for ways to enliven the boredom, and rest and recreation periods often result in high jinks.

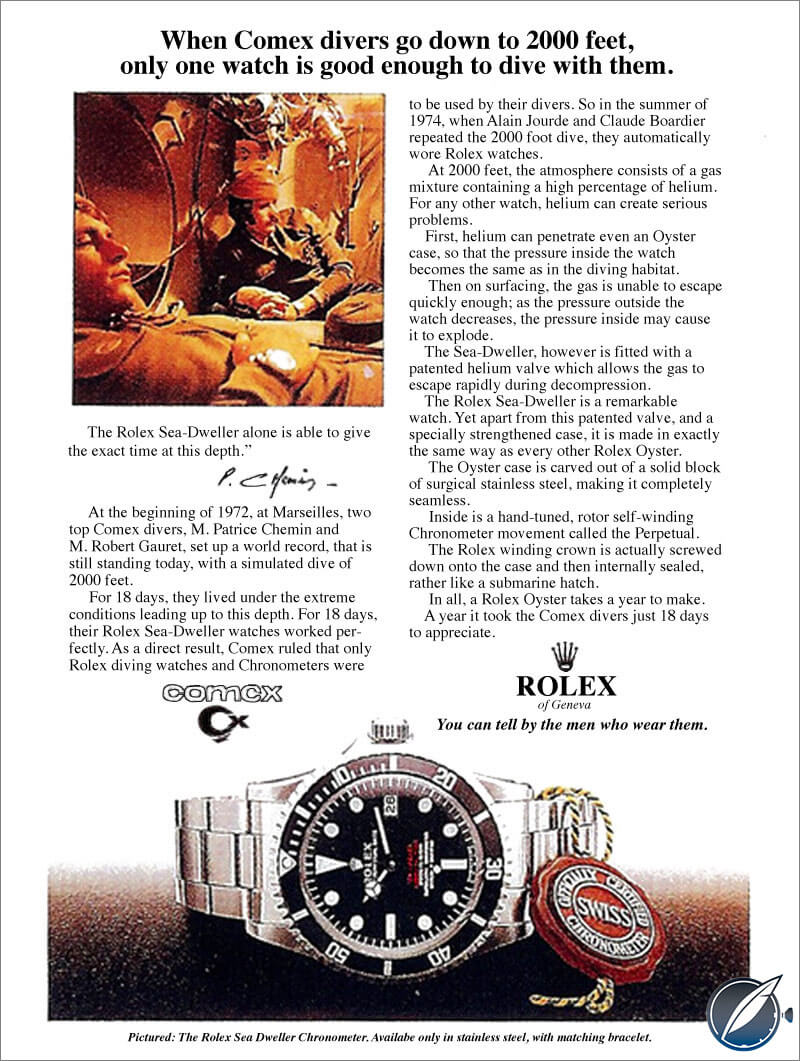

In the mid-1980s Band was on a job trenching a telephone cable between Karachi and Fujairah, supervising two French Comex divers who had previously been involved in the French marine exploration company’s Janus IV project, working at record depths down to 501 meters.

1980s Rolex Sea-Dweller advertisement

After the project was completed and the divers were relaxing with a bottle of whisky on board the barge, one of the Comex divers was vaunting the accuracy of a quartz watch he had been given by Rolex to test (possibly a now highly-coveted Beta 21). So Band, who was wearing his indestructible Seiko 150 at the time, asked, “Do you think your Rolex could beat my Seiko at watch conkers, monsieur?”

This was a game that Band had devised to while away lengthy rest periods. Like the English game played with dried chestnuts on a string, it involved holding his Seiko out by the bracelet and letting his opponent take a swing at with his watch, whatever that may be, and then returning the blow until one or other watch (or its owner) caved in.

Band’s Seiko had acquired a few dents and scratches along the way but had soundly beaten off all comers, including a “huge Omega” that he subsequently identified as a PloProf, no less.

After inquiring “what eez conquers?” and receiving an explanation of the rules, with a little encouragement from his colleagues the Comex man duly agreed to play conkers with his quartz Rolex, which he was certain would easily see off a mere Seiko. After asking him several times, “Do you really want to do this” and enumerating other victims that had been felled by the Seiko, Band let him take first shot, which merely added another scratch to his Seiko’s bezel. Again, he offered the Frenchman an opportunity to withdraw, but he “persisted and signed,” as they say in France.

The blow from the Seiko was fatal, with the Rolex’s crystal, hands, and case ending up scattered to the four corners of the room. The Comex man presumably reported back to Rolex that after due consideration, the watch was “not fit for the rigeurs of diving life.”

1952 Rolex Oyster Perpetual – the Everest connection

As the son of an oil company executive, Band spent the first nine years of his life in Venezuela, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and Oman. One of his earliest childhood memories is of his father George giving a presentation to an appreciative crowd of Europeans and English-speaking East Pakistanis at what he remembers as some sort of church hall.

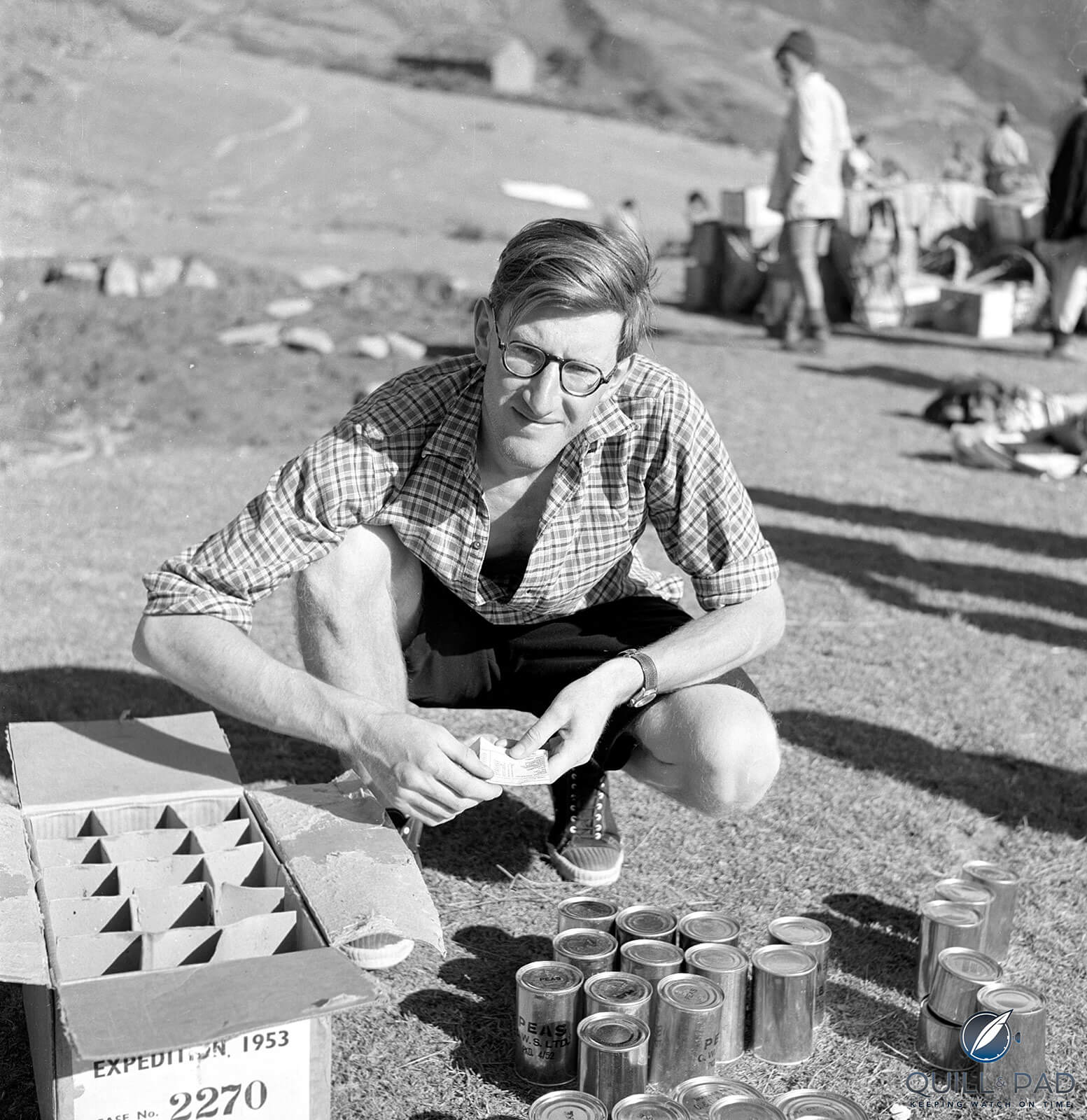

Eagle-eyed observers of Rolex memorabilia, and in particular Rolex Explorer memorabilia, may have already noticed that Nigel Band shares his surname with one of the members of the team led by Sir John Hunt that conquered Mount Everest in 1953. Nigel’s father George Band was the youngest member of that team, recruited while still a geology student at Cambridge University.

George Band selecting the day’s rations, Mount Everest 1953 (photo courtesy Royal Geographical Society)

Described by Sir John Hunt as “the expedition wit, intelligent and amusing,” George Band was the team’s official wireless operator and much appreciated for his catering skills, which ranged from opening tins of conserves to skinning yaks.

George Band and George Lowe skinning a yak on Mount Everest (photo courtesy Royal Geographical Society)

In spite of suffering altitude sickness and a protracted bout of dysentery on what was his first trek high in the Himalayas, he helped pioneer a way through the Khumbu icefall and was first out of base camp at 21,000 feet to greet the descending Hillary and Tenzing on their descent from the peak.

George Band congratulating Tenzing Norgay on his descent from the peak of Mount Everest (photo courtesy Royal Geographical Society)

Over the years the Everest team continued to hold regular five-yearly reunions to celebrate the event, sometimes at Pen-Y-Grwyd in Wales, where they had trained for the expedition, so Nigel Band grew up surrounded by family friends and acquaintances who were household names at the time.

On one occasion he took Tenzing Norgay’s wife into London to choose cassettes of “the latest pop music” for her family back home – Status Quo and Queen he remembers. He also recalls his mother turning up to collect him from boarding school one half-term “in a large blue Citroen estate, with Ed Hillary in the passenger seat.” This earned him considerable kudos with his incredulous classmates, but on the way home, “Ed offered to drive and promptly crashed the car while negotiating the slip road onto the M4 motorway.”

From these meetings he recalls Jan Morris (Times reporter on the 1953 expedition who very recently passed away, and James Morris at the time) giving a talk, leaning on the lectern, and intriguingly twirling her spectacles with one hand as she spoke, in stark contrast to the other members’ more formal presentations. And during a talk by Sir Edmund Hillary, one stalwart leaning over to another member and muttering “of course it wasn’t a Rolex he was wearing at the top, it was a Smiths . . . ”.

But that’s a topic for another article.

At another event a journalist sought to “troll” Sir Edmund Hillary by asking him to comment on speculation that George Mallory had in fact summited Everest in 1924 before dying on the descent. To which Hillary responded, in typically laconic fashion, that he’d had a damn good run as conqueror of Everest and would be quite happy to let someone else take over.

George Band continued to play an active role in the international mountaineering community and with Himalayan organizations for the rest of his life, writing several books and being awarded the OBE in 2009 in recognition of his services to mountaineering. His achievements are too many to enumerate here, but include his participation on the successful 1953 Everest expedition and what was his crowning glory, the 1955 conquest of the “Last Great Mountain,” Kangchenjunga, together with Mancunian builder Joe Brown.

As is well documented, Rolex had been equipping mountaineering expeditions with watches for some years, and the Everest team carried 13 Oyster Perpetual certified chronometers with them in total, six presented for the 1952 Cho Oyu expedition and seven for the new members of the 1953 team. George Band’s Oyster Perpetual Reference 6098 was one of the latter.

George Band’s 1952 Rolex Oyster Perpetual (photo courtesy Nigel Band)

This version of the Oyster Perpetual features the domed “bubble-back” case, required to allow room for the automatic winding rotor mounted on what was originally a manual movement. It was not until the slimmer 1030 movement was introduced, designed from scratch as a self-winding movement, that the Oyster Perpetual and the Explorer boasted flat case backs.

The back of this particular watch is engraved “EVEREST 1953” and “G.C. BAND,” with a fainter engraving of the Rolex crown and “H6” indicating that it was number six of the second batch of watches presented to the expedition team by Rolex.

George Band’s 1952 Rolex Oyster Perpetual from the back (photo courtesy Nigel Band)

George Band’s other Rolex: 1953 Rolex Oyster Precision with “Explorer dial”

Kangchenjunga was once believed to be the highest mountain in the world and deemed unclimbable. Even after it was determined that K2 and Everest were higher, it remained the most daunting of the three for mountaineers and is still venerated by the local population as the holiest of mountains.

Kangchenjunga and its satellite peaks form a huge mountain massif of five peaks that straddle the border between India and Nepal. Extreme weather conditions and high avalanche risk due to its proximity to the Bay of Bengal made it what Everest leader Sir John Hunt called “the most difficult feat in mountaineering.”

George Band on the western approach to Kangchenjunga, 1955 (photo courtesy Royal Geographical Society)

Building on a route carved out nearly 50 years earlier by devil worshipper and (rather incongruously) enthusiastic mountaineer Aleister Crowley, aka “the wickedest man in Britain,” George Band and Joe Brown summited Kangchenjunga on May 26, 1955, usually reported as “stopping just short of the peak out of deference to local religious beliefs.” The expedition had been planned as a reconnaissance trip with a view to summiting in 1956, and the team had only obtained permission from the Chogyal of Sikkim to explore Kangchenjunga at the last moment on the understanding that they would go nowhere near the top.

For this expedition Rolex had given George Band a black-dial Oyster Perpetual Precision Reference 6150 with the now-familiar 3-6-9 dial and Mercedes hands.

The success of the Kangchenjunga expedition and the fact that the first Explorer models had syringe hands for the first 18 months (not to mention the fact that neither Hillary nor Tenzing were wearing Rolex watches on the peak of Everest, as has now been proven) surely makes it the true spiritual ancestor of the Rolex Explorer rather than the Oyster Perpetuals used by the Everest team. This watch was sold at a Phillips auction by the Band family in 2017.

The Kangchenjunga Rolex 6150, an Explorer in all but name (photo courtesy Eszter Faykiss/Loupiosity)

George Band passed away in 2011 at the age of 82, having taken part in a Kangchenjunga reunion expedition in the Himalayas at the tender age of 76 and reconquering the Breithorn with the Alpine Club aged 78. His Oyster Perpetual now belongs to Nigel, who wears it occasionally, still on the Fixoflex bracelet that his father preferred for both of his mountaineering watches.

Nigel fully understands the importance of keeping the Oyster Perpetual in absolutely original condition – just as his Sea-Dweller, which is still a working tool watch, has been maintained in working condition for the purpose for which he bought it.

Nigel Band’s 1986 Rolex Sea-Dweller and 1952 Rolex Oyster Perpetual (photo courtesy Nigel Band)

Nigel remembers that his father wore both the Oyster Perpetual and the Precision continuously throughout his childhood, with a preference for the black-dial Precision due to its better legibility. They were only retired from active service when somebody presented him with a newfangled electronic timepiece with a built-in altimeter. Which proves that you can bring the mountaineer down from the mountain, but you can’t take the mountain away from the mountaineer.

I asked Nigel whether his father’s love of mountaineering had rubbed off on him in any way. “Not really, I’ve done some hillwalking in the UK but beyond that I just don’t have a head for heights – I’d much rather be underwater!”

It may be a coincidence, but it is curious that in their totally different chosen fields, both father and son ended up wearing breathing apparatus and Rolex watches.

*This article was first published on November 25, 2020 at Professional Diver Nigel Band And The Unusual Rolex Sea-Dweller And Oyster Perpetual Models That Plumbed The Depths And Scaled The Heights.

You may also enjoy:

Khanjar And Qaboos Rolexes: Are They The Vintage Watch Industry’s Blood Diamonds?

Zen And The Art Of Wristwatch Maintenance: The Benefits Of Learning To Service Your Own Watch

Why I’ve Never Owned A Rolex – And Why I Might Yet (Update: I Do Now!)

5 Tool Watches I’d Buy If I Didn’t Want to Spring For A Rolex Submariner

The Golden Age Of Rolex Movements Part I: Sowing The Seeds Of Greatness

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!