by Ken Gargett

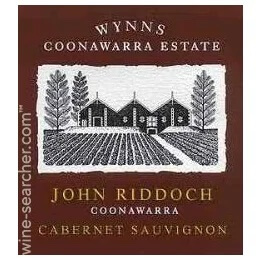

Without question, the most important wine producer in Coonawarra today is Wynns Coonawarra Estate. Like Coonawarra, it has had its ups and downs. But these days it makes the most important wines from the district, most notably the Wynns flagship, John Riddoch Cabernet Sauvignon.

The Gables at Wynns

John Riddoch’s role in establishing the region and winery that would become Wynns is detailed in World-Famous Wine Regions: Coonawarra, South Australia and elsewhere, so I won’t rehash that here. There can be few wine lovers who would not immediately recognize the iconic triple-gabled winery featured on the label of Wynns wines, a label designed by Richard Beck.

What attracted a Melbourne wine merchant to such an isolated region? Samuel Wynn was originally known as Shlomo Weintraub when he fled Russian-occupied Poland for Australia just before World War I at the age of 21 years. Wynn eventually ended up running a wine bar in Melbourne and an influential wholesale wine business, supposedly unaware that he had changed his name from the German word for “wine grape” to an old English word for wine (a career in the wine industry was surely inevitable). Wynn did, however, come from a family of winemakers and he built quite an empire with restaurants, bars, wholesale business, and considerable vineyard holdings and wineries.

Among the wines he served were table reds from Coonawarra purchased from Woodley’s. Samuel Wynn knew the quality offered by the region and wines made by Bill Redman. That said, there is some debate over whether it was Samuel who wanted to invest in the region or his son, David. A clue might be that when they finally got their hands on what would become Wynns, it was David who ran the place.

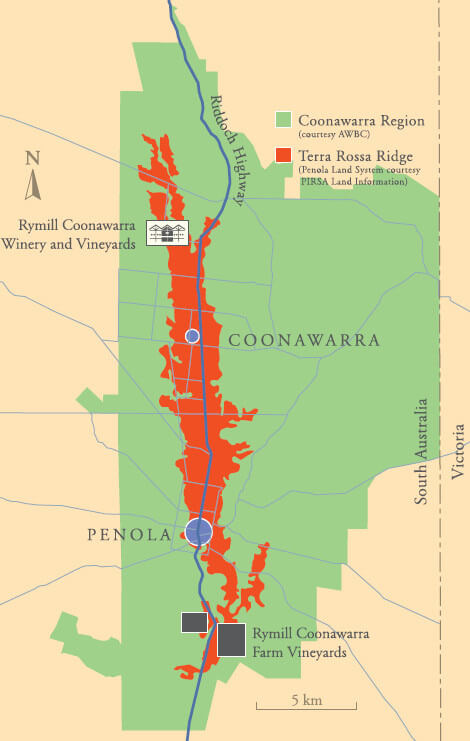

Coonawarra in South Australia

Ken Ward, who would later become the Wynns’ winemaker, claims to have overheard the telephone conversation when Tony Nelson sold to the Wynns. The first offer was £15,000, which was rejected. The offer was increased in increments of £2,500 until it reached £25,000, which was accepted. Other reports suggest it was sold for £22,000.

David Wynn immediately appointed Ian Hickinbotham as winemaker, also destined to become a legend in the industry. Hickinbotham passed away earlier this year at the age of 88. In his book Australian Plonky, Hickinbotham indicates that the debate over who was behind the purchase may have been more about price, with David upping the offer without speaking to his father. The book also offers some gems about life in Coonawarra at the time, including a local agent describing a stockman’s dinner with a horse’s hoof protruding from the pot.

The first Wynns wine was a Shiraz, the 1952 Claret. It was made with no electricity, just a basic generator and steam-driven pumps. Pruning was done by Hickinbotham’s mates from the local footy club. It was not long before the quality began to be recognized. The 1953 Wynns Coonawarra Estate Claret apparently gained a berth in the cellars aboard the Royal Yacht Britannia.

In 1954, Norm Walker, yet another luminary in the Aussie wine firmament (Norm’s father, Hurtle, was born at Magill and at 14 joined Auldana, later gaining fame for his sparkling wines, while Norm’s son, Nick, together with good friend, David O’Leary, founded the O’Leary Walker winery in the Clare Valley). Norm Walker made the first Wynns Coonawarra Cabernet from seven tons (other reports suggest just three tons) purchased from local growers. Remarkably, it is believed that this was the first 100 percent Cabernet ever made in Coonawarra.

The first great wine under the Wynns label was the 1955 Michael Hermitage, 100 percent Shiraz. David Wynn had spotted two barrels from the vintage that stood head and shoulders above the rest and decided that they should be bottled separately. Another report suggests that it was a single 2,300-liter vat (as happened in so many places like this, no one was thinking of what future generations might like to know at the time, hence there are so often conflicting reports). Yet another report has it as a single second-hand fortified cask. The wine was named after David’s son but was a one-off, at least until the 1990 vintage when it was revived and the “Michael Shiraz” became part of the core range provided the vintage was good enough.

Early releases by Norm Walker, the 1955 and 1956 of the famous Cabernet – it would not become the Black Label for many years yet, and was actually bottled under a white label in the early days – were blends, 80 percent Cabernet and 20 percent Shiraz, before the wine reverted to 100 percent Cabernet Sauvignon. Since then, the only exception was the 1969, a Cabernet Hermitage.

Wynns has always enjoyed the benefit of a star-studded array of Australian winemaking talent at the helm. After Hickinbotham and Walker, Jock Redman, Bill’s nephew, was in charge from 1961 to 1968; Ken Ward followed from 1971 to 1977; John Wade, well known in the west, from then till 1985; and Peter Douglas until 1997. It was during Wade’s tenure that the John Riddoch Cabernet was first introduced.

Coonawarra wine region

Wynns today

After Douglas, Sue Hodder took over and she is still chief winemaker today. Under her supervision, Wynns has arguably enjoyed the most impressive period in its history. And this at a time when the region has not quite fallen from grace but come back to the pack. Hodder started the single vineyard program and she has overseen numerous innovations in the winery, often with her colleague, Sarah Pidgeon. Hodder also presided over two of the most incredible tastings I’ve been privileged to attend: every Black Label Cabernet from Wynns right back to the very first one for the vineyard’s fiftieth anniversary and then repeating it for the sixtieth.

Sue Hodder, Wynns’ chief winemaker

Perhaps most notably, Hodder has worked very closely with viticulturalist Allen Jenkins, who joined Wynns in 2000. Jenkins has just retired, but between the two of them they worked diligently to improve quality across the vineyards, replanting 25 percent of the vineyards across each decade. Their partnership was recognized by AGT Wine Magazine in 2010 when the pair was named Winemaker of the Year, the only time a collaboration has achieved this feat.

On Jenkins’ retirement, Sue Hodder noted that it would not only be Wynns who would miss him, but “the broader Coonawarra community,” stating that, “Allen has literally transformed the landscape in Coonawarra though his viticultural efforts. Furthermore, he has had an impact on the way we think about everything from the history to the land and certainly the wines. A profound contribution and a massive legacy.” Normally, such adulation is thrown around at retirements and everyone knows that it is the time to say nice things. In this case, it is undoubtedly true.

During their collaboration, Jenkins ran a close eye over the Johnson Vineyard, identifying the 8,000 vines considered the best performers. The Johnson Vineyard was planted with Cabernet in 1954, making it the oldest surviving Cabernet vineyard in the region (Shiraz was first planted in this vineyard in 1924, largely for distillation).

Over time, Jenkins narrowed the 8,000 down to the top 144 vines, largely those that showed superior drought resistance. From there, he went to the best 48 vines and subsequently, the very best 18 vines, including those showing good resistance to trunk disease. Finally, he settled on a top five. These are the vines to be used as the source for all future plantings. Hodder and Jenkins have also worked extensively on drought tolerance, leaf plucking, water management, shoot thinning, pruning, and more in a never-ending search for consistency throughout the vineyards.

The Alexander Vineyard has also been important as here Hodder and Jenkins have conducted experiments on nine different rootstocks as well as own roots. Usually, the Alexander Vineyard ripens later than most and the fruit is “bigger and more powerful” according to Hodder. It often becomes a component of the John Riddoch for that year.

From 1984 to 1988 Mildara made wines, very successfully in some cases, from this vineyard before being gradually sold to Wynns. The Alexander family originally obtained the land back in 1892. At the time, it was ten acres of Shiraz, ten acres of Cabernet, and a lot of red gums. James Alexander had been a banker who got his hands on a diamond mine lease in South Africa in the 1860s. He headed off to seek fortune and fame, but had no luck and so a decade later sold the lease to a very young Cecil Rhodes. Rhodes did make a fortune from it. Alexander returned to Australia and married Riddoch’s daughter. His executor sold the vineyards to Mildara (now of course all part of the mega empire).

Prior to the influence of Sue Hodder, much had been achieved. As well as planting Cabernet in the Johnson Vineyard, the Davis Vineyard was planted soon after in 1957. Other vineyards followed. The early Wynns winemakers are believed to be some of the first in the world to understand malolactic fermentation, thanks especially to Ray Beckwith at Penfolds (scientists of the day thought that warmer climates for grapes meant that the grapes contained no malic acid). The claim has often been made that without Beckwith, there would have been no Grange.

Wynns through the ages

In the 1950s Wynns made some impressive wines; 1954 showed superbly at both anniversaries, while 1959 was sublime at the sixtieth, looking far better than it had a decade earlier. Of course, the old saying about old wines applies: “There are no great wines, just great bottles” (which I think should be amended slightly to “just great corks”).

The 1960s was when Wynns and so many others hit their stride. Sue Hodder has said of this decade that “it informs our winemaking today.” Some vintages were not made due to conditions, notably 1961, which was affected by frost, and 1963 as it was too wet.

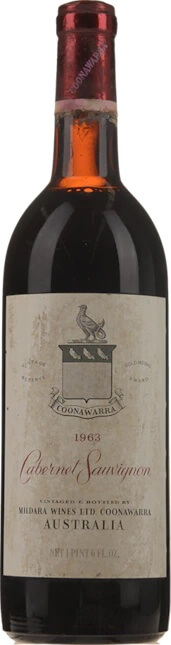

Mildara Coonawarra Cabernet Sauvignon 1963

And yet Mildara released its famous 1963, the Peppermint Pattie, still brilliant today. The theory is that Mildara picked early and skipped the rains; others think that some McLaren Vale material might have found its way into the wine, but who really knows? Ward was not excited by the 1969 vintage and hence made it as a Cabernet Hermitage.

More important than the individual vintages, Wynns wisely took the opportunity to buy as much vineyard land as it could – remember that this was a time when there were still only the two wineries in Coonawarra. The 1960s was another decade in which the winery operated without electricity; 1968 is believed to be the first vintage where the winemakers used American oak. At the time, the best years were considered to be 1960, 1966, and 1967.

As a broad generalization, the 1970s was the wettest decade experienced in Coonawarra. Wynns also had to deal with young vineyards as many of those planted earlier were now in production. Wynns had 214 hectares of which 42 percent was Cabernet. We were also seeing greener-styled wines encouraged by show judges who seemed enamored of herbaceousness. Mechanical harvesting began in 1974 (the leafy canopies also contributing to the overall greenness). Machine pruning followed in 1979.

This was the era of the white wine boom and it meant that winemakers were forced to graft many vines over to white varieties. An astonishing 50 percent of the terra rossa was planted to Riesling. Winemaking techniques tended to follow what suited whites, stainless steel fermenting tanks being an example. Small oak would not be used here until 1985 when it was introduced by John Wade.

Wynns did win Australia’s most prestigious wine award, the Jimmy Watson Memorial Trophy, the first time a Coonawarra wine had achieved that, with its 1976 Black Label Cabernet, which seemed available for many years after release. The top years of the 1970s were considered to be 1970, 1971, 1975, 1976, and 1978.

Having finally won a Jimmy in the 1970s, Coonawarra made it a habit of it in the 1980s, winning in 1981, 1982, 1985, 1986, 1987, and 1989, though rarely since then. Much of the plantings by Wynns in earlier decades were now mature, and the winery purchased another 200 hectares of vineyards. And then Penfolds and the mega empire purchased Wynns! After passing through successive ownership, Wynns is part of Treasury Wines Estates.

The 1980s was when Wynns began the use of smaller barrels, increasing the amount of barrel fermentation, and a much greater emphasis was placed on the importance of pH. This was also when Wynns really started work in the vineyards: 1980, 1986, and 1988 were considered the top years, but 1982 was also a superb vintage and this was the first release of the flagship John Riddoch Cabernet.

By the 1990s, the demand was for full-bodied reds. Sue Hodder has talked about pressure to make “monsters,” but that of course is not Coonawarra’s thing. Wynns purchased a further 300 hectares in 1993. By 1996, the total holdings had reached 1,275 hectares, of which 428 were Cabernet. Winery capacity was increased – Wynns could store 2,000 barrels and had capacity for 3,400 tons on skins.

Winemaker Peter Douglas has suggested that 1990 was the vintage of the century, while others would opt for 1991; 1996, 1998, and 1999 were three more stunning years; while 1995 is generally considered the least of the decade, but it still managed to offer a fine wine. An impressive decade all round.

By 1998, production of Black Label Cabernet hit 80,000 cases, though that has decreased in recent years, depending on vintage. In the early part of the decade, some American oak was still used. By the end of the 1990s, 20 to 25 percent of the wine saw new oak barrels.

Since then, much of the work at Wynns has been in the vineyard and the winery has been rewarded – the wines since 2000 being the most impressive of all. Trials in every aspect of the work continue, seeking the tiniest of improvements. This is perhaps best reflected in the 2011, a horrible vintage and one that in the past would almost certainly not have been released. Yet now Wynns was able to release a fine Black Label.

The best since 2000 are considered to be 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, and, finally cracking the even-year curse, 2015. Add 2016 and 2018 to this; 2019 is another odd year to shine, and although early days 2020 looks like a small but excellent vintage. The hype around 2021 suggests it could be one of the greatest of all.

One point must be made. The longevity of these wines continually surprises everyone. It confirms what Bordeaux has known for generations: Cabernet is a grape that can age amazingly well. Do not be afraid to put these wines away for as long as you want provided you have good cellaring conditions. Your children, and grandchildren, will thank you. Not a bad legacy for a wine that is currently available for a mere AUD$45 (and was recently discounted down to a criminally low $25).

Wynns John Riddoch Cabernet Sauvignon

Even if John Wade had never released the flagship Cabernet, the John Riddoch, there is no doubt that Wynns would have firmly cemented its reputation as the region’s leading winery and one of the best in all Australia. This great Cabernet, however, sits comfortably with Australia’s best (most of the rest hailing from Margaret River). The esteem with which it is held is evident in that it became only the second Australian wine to be sold via La Place de Bordeaux, the system for selling great Bordeaux, which now includes some special wines from around the globe. The John Riddoch followed Jim Barry’s Armagh, and recently Penfolds Bin 169 Coonawarra Cabernet Sauvignon joined them.

Terra rossa in Coonawarra

Wade released the early John Riddochs based on the older Cabernet blocks located on the famed terra rossa, believing them to provide “concentration, richness of flavor, and ripeness.” At least one winemaker at the time realized that the trend to herbaceousness was not appreciated by all.

Wade had ordered new French oak barriques and hogsheads and the 1982 spent two years in 100 percent new oak. It still drinks beautifully. The wine made a huge impact, which was built upon by subsequent vintages. Peter Douglas’s first vintage, 1986, was a superb one and his John Riddoch was brilliant, further increasing the reputation of the wine. The 1990 was another to create great excitement.

Among the work done by Sue Hodder and Allen Jenkins in the vineyards has been a determined effort to ensure that the grapes used for John Riddoch are as good as they possibly can be. This has resulted in the removal of the pyrazine characters that can impact Cabernet, increasing the green notes. It has also meant that the yields from vineyards are equivalent to those for a Bordeaux First Growth. These days, almost all grapes for John Riddoch are hand-harvested.

After sorting, the grapes will usually be lightly crushed. Batches are dealt with individually. Fermentation at around 28ºC to 30ºC is in small stainless steel open fermenters, although a small percentage of additional parcels are made in static or vinimatic fermenters. After 12 to 15 days, the wine will be pressed into a combination of medium-toast, French-coopered hogsheads and barriques.

Minimal racking, then rigorous barrel selection will take place after 14 to 20 months, depending on the vintage. The wine is bottled under screwcap (and has been since the 2004 vintage). It is given 18 months further aging in the cellars before release. The current vintage sits around AUD$150. Given it is usually favorably compared with some of Bordeaux’s better wines, that makes it amazing buying.

John Riddoch is only made in the better vintages. There was no 1983 (often referred to as the Biblical vintage as it copped floods, fires, storms, and pretty much everything one could think of). There was no 1989, a poor vintage, or 1995, considered “the least” of the ’90s.

There was none made from 2000 to 2002 (not so much because of vintage conditions but because of work that was being conducted in those vineyards), and 2007 was affected by a bad frost. Two thousand eleven was just a horrible year, and the team did not think that the fruit it could access in 2014 and 2017 quite made the grade. Wynns notes that only one percent of its Cabernet is ever used for John Riddoch.

Sue Hodder is fond of saying that “vintage trumps everything,” but she has also noted that sometimes, the vintages don’t always tell the full story in the early days. The 1994 John Riddoch is an example as it has blossomed to a level no one thought likely in its early days.

Wynns 2018 John Riddoch Cabernet Sauvignon

Wynns John Riddoch Cabernet Sauvignon 2018 tasting notes

The current release is the superb 2018, and we can expect this wine to show the incredible longevity for which the line is known. This is a great vintage for John Riddoch. The wine spent 15 months in “new (18 percent) and seasoned French oak hogsheads (47 percent) and barriques (53 percent).” So well structured and so finely balanced is this vintage that you could drink it today, but it is a wine that will age and improve for many years. As enjoyable as it might be now, this wine will get considerably better.

The color is magenta/dark purple. While oak is evident, the wine is so well balanced that it is as close to invisible as one could wish. Utterly seamless with a supple, creamy texture, there are notes of chocolate, cassis, blackberries and mint, florals, coffee beans, and even the merest hint of red berries.

Beautifully refined, it is both elegant and powerful, a fine line to tread. The intensity is maintained throughout with good acidity and very fine, silky tannins. It has the structure and fruit to last and improve for another 10, 20, or 30 years. An exquisite Cabernet, one of Australia’s best. 98.

For more information, please visit www.wynns.com.au/en-au/wine/cabernet-sauvignon.

You may also enjoy:

World-Famous Wine Regions: Coonawarra, South Australia

The Sensational (Grange) G5 Wine, Peter Gago, And The History Of Penfolds

Penfolds Bin 60A 1962: Australia’s Greatest Wine Ever (Or Certainly A Serious Contender)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!