by Ken Gargett

The annual doctors’ lunch (a bunch of friends who are mostly from the medical profession) was even more welcome this year as it was the first lunch with friends I’ve been able to attend in more than six months thanks to border closures and the ever-changing COVID-19 restrictions in Australia. I swear that tree stumps would look at some of our politicians and question evolution.

The lunch is always great fun and inevitably a cavalcade of wonderful wines. Doctors tend to be a competitive lot so there is always much good-natured jostling to have their contribution declared “wine of the day.” And as they don’t trust each other to be objective, I sometimes get the “honor” (?) of nominating the winner.

This year, a glorious bottle of 1989 Krug reigned supreme. Needless to say, there was more controversy than for a Formula 1 final race. I was seated between two champagne lovers, both very knowledgeable. Mine was poured and the server went to my right. The two of us looked at each other and just went “wow!” it was so good. Our glasses were long emptied by the time the poor server had managed to maneuver her way around the full table – it took her about 15 minutes.

Apparently, by that stage, the champagne had completely fallen flat. It can happen, although you’d expect it more from an older vintage. So despite the chorus of boos from those on my left, I was sticking to the decision.

There was, however, no argument about the “red of the day”: a glorious 2010 Biondi-Santi. A great vintage from one of Italy’s – and indeed the world’s – most famous wines, the one that is really responsible for the Brunello di Montalcino appellation.

Biondi-Santi and the Brunello di Montalcino appellation

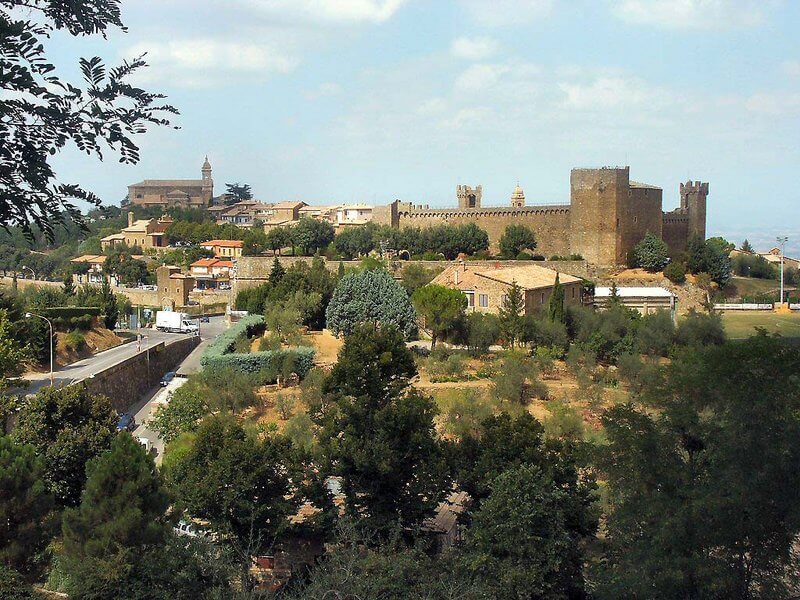

Brunello is a famous Tuscan region using 100 percent Sangiovese. Over the years, there have been some hiccups, but the region is now regarded as one of the finest in the world. It is in the province of Siena, south of Florence. The name Brunello came about as a diminutive of bruno (brown), the name given to the local grape.

Montalcino, Tuscany

Later, it was determined that this was the same as Sangiovese. The appellation was one of the very first in Italy to receive DOCG status, achieving the honor in 1980 (four appellations received the designation the same day). I will be looking at all this in more depth in the near future, but today the focus is on the great Biondi-Santi.

Sangiovese grapes in Montalcino (photo courtesy O. Strama/Wikipedia)

There are very few estates to which one can point and state categorically that this was the genesis for a distinct style and an entire wine region, but Biondi-Santi is one. It is well known that the Biondi-Santi family has been growing grapes and making wine in this region for the best part of two centuries.

Around 130 years ago, give or take, Ferruccio Biondi-Santi isolated the clone of the grape that would be the foundation for the region, a clone of Sangiovese: Sangiovese Grosso BBS11. Ferruccio’s grandfather, Clemente Santi, had won a couple of silver medals for his reds at an agricultural show in Montepulciano back in 1869 and also an award at the Universal Exposition in Paris for his 1865 red. Clemente’s daughter married Dr. Jacopo Biondi and their son, Ferruccio, took the hyphenated name that would later become so famous. Other sources suggest Ferruccio was Clemente’s nephew. It hardly matters now.

The tradition at the time was to vinify a range of varieties, including whites, together. Ferruccio decided to make his wine solely from this clone. And Brunello di Montalcino was born.

Fame was hardly instantaneous. The region was making a sweet Moscadello di Montalcino at the time and it was much more popular. Ferruccio was determined to make a red that could age and improve for many years.

Ferruccio was posthumously named “the inventor of Brunello” by an interministerial committee in 1932.

History of Biondi-Santi

Ferruccio Biondi-Santi, who passed away in 1917, was succeeded by his son Tancredi, who had studied oenology. Tancredi was subsequently named an ambassador for Montalcino and mentored many other winemakers in the district. He was effectively the original consultant oenologist in Italy.

Tancredi was famous for walling up many of the best vintages in the cellar at the onset of World War II to prevent them from being plundered by the Axis forces as they headed to the village. Among many, they saved a couple of bottles of the 1888, which the house still held. And apparently still does. The 1888 was the very first Brunello di Montalcino ever made. They last tasted it in 1994 and it was still in stunning form. The good news is that – and how extraordinary is this? – a couple of bottles still exist. The house also has some of the legendary 1891.

Franco took over in 1970, at which time the estate was a mere four hectares. He oversaw the expansion to 25 hectares. The estate covers five different parcels, which are blended together to create the final wine. Other sources have suggested 26 hectares over three sites, though five seems generally accepted.

Brunello vines in Montalcino (photo courtesy Giovanni/Wikipedia)

There is a story that the wines were unknown in London until the famous 1955 was served at a dinner at Buckingham Palace in 1969, greatly impressing Her Majesty. It was so well received that demand skyrocketed, although production has always been tiny. The 1955 Riserva was so highly regarded that the American magazine Wine Spectator named it as the only Italian wine on its short list of the very greatest wines of the twentieth century.

Until the late 1960s, there was not another single serious producer of Brunello and no other commercial producer until after World War II. Now there are several hundred, but without the various generations of the Biondi-Santi family, who knows if there would even be a wine industry of note there. What is curious is that many have veered away from the elegant, age-worthy wines of the estate to richer, often noticeably oaked styles. These are certainly enjoyable wines, but they hardly resemble those from which they have descended.

There have also been suggestions of many producers to include “other varieties,” often international ones. This was a topic of fierce debate in the region, the Biondi-Santi family steadfast in its opposition to anything other than 100 percent Sangiovese. Franco was instrumental in fighting the good fight to retain Brunello as a 100 percent Sangiovese wine. He prevailed. On top of that, the Brunellogate scandal is a very sore subject and a topic for another day.

Biondi-Santi Brunello di Montalcino Riserva Greppo 2010

The “standard” wine from the estate is often known as Greppo. There is also a Rosso di Montalcino and, in the years deserving, a Riserva, usually no more than a maximum of 15,000 bottles. The “standard” is usually around three times that, with the Rosso around 20,000 bottles. A ballpark price of the Greppo is around €160 at the moment, though this will vary from country to country. The Riservas are likely to be several times that. The Riserva is not made in every vintage.

It is said that Franco would deliberately inflate the price of his favored vintages in an attempt to stop people buying them, happy to keep them in his cellars. He was known for saying that he wanted the wines he made to never be old enough for drinking.

The current vintage for the “standard” seems to be the 2015 and for the Riserva 2012, Franco’s last wine. It is only the 39th Biondi-Santi Riserva since 1888; 2013 will follow it. There is word that the team is looking then at 2017. Given that both 2015 and most especially 2016 were such stunning vintages for Brunello (I’ll be looking more closely at 2016 shortly), it seems impossible to imagine that we won’t see Riservas for them – or perhaps they are simply a given, whereas 2017 requires more consideration. Time will tell.

Biondi-Santi today: Jacopo Biondi-Santi and sale of the estate to EPI

Generations of the Biondi-Santi family have run the estate known as Il Greppo. Sadly, Franco Biondi-Santi, grandson of Ferruccio, passed away in 2013 at the venerable age of 91, having inherited the estate in 1970. Franco’s son, Jacopo, took over. Things, however, were far from that simple. Franco and Jacopo had fallen out rather severely as far back as 1991, at which time Jacopo had left the business (apparently he still had a 23 percent share) and established his own winery, Tenuta Castello di Montepò in the Morellino di Scansano appellation in the Tuscan Maremma.

Shortly before Franco passed, Jacopo was quoted in an interview with English wine magazine Decanter suggesting his father was jealous of his success (when you run one of the world’s great wine estates, I am not all that certain why you would bother wasting time with jealousy elsewhere, so one wonders if this was simply said out of acrimony). Jacopo was quoted as saying, “My father’s very jealous . . . because I created a new name and he preserved only tradition. He created nothing else . . . he has prepared nothing. If he wants to sell, fine, I’m happy. I have my own wine. If he dies, I have to pay inheritance tax on the estate and on the trademark.” Christmas may have been strained.

Sadly, it seems Franco passed before the rift could be healed (one hopes that this is not so and certainly some stories now suggested by various descendants indicate that they were closer than we have been led to believe, although after his father’s passing Jacopo credited his grandfather with teaching him how to make wine rather than Franco).

This left Jacopo in control (he also continued to run his estate in Maremma). He was already in his sixties, but he undoubtedly knew what was at stake and has spoken about how he was prepared for the challenge his entire life. Fortunately, the 2013 vintage was a glorious one. Who knows what questions would have been raised had Jacopo’s first wine not reached stellar heights.

There have even been comparisons between the 2013 and the legendary 1955 (this may have been hyperbole strewn around in the aftermath of the new vintage and the ascension of Jacopo as with the best will in the world, ranking 2013 with 1955 seems a leap – 2012 perhaps?). Interestingly, large quantities of older vintages were sold off in 2013. Was this simply to raise funds? To erase the past? A touch of spite? The search for a clean slate? Those inconvenient inheritance taxes? Or did they simply get an offer they could not refuse? Who knows and it matters little today.

Jacopo was clearly intent on modernizing the estate, although he did not destroy all traditions, maintaining fermentation on native yeasts and the use of Slavonian oak casks in which the wines spend considerable time. He did, however, work to bring forth more complex characters and a deeper color in the wines. He moved from the oft-used hydraulic basket press to the more modern soft bladder press. Maceration periods were doubled to 25 days with the temperatures lowered slightly. Racking was increased.

While we will never be privy to decisions within the family, it was not long before the decision to sell the estate was made. This was shocking news at the time and reverberated around the wine world. It is believed that the inheritance laws in Italy played their role in forcing the sale.

Christopher Descours’ French group EPI had taken an interest in 2016 (as seems inevitable, dates vary, with 2017 quoted by some, but it was around this period, give or take a year or two), but then in 2019 Jacopo left the business completely. Finally, in 2020 his son Tancredi, who works with him in the Maremma business, sold his share and EPI became sole owner. Shocking, yes, but comfort was given by the knowledge that EPI is also the owner of Charles Heidsieck, one of the great champagne houses and one that has very much benefited from that ownership.

That is not EPI’s only winery or, indeed, champagne house. It also owns Piper-Heidsieck, another house very much on the improve, and Rare, the house hived off from Piper, which produces small quantities of a great prestige champagne. EPI also has interests in Luberon and the Rhône as well as various distribution businesses. Biondi-Santi will certainly not be its last wine acquisition.

Who knows what the future holds for Biondi-Santi, but under the new ownership I think we can be certain it will not disappoint. One early development is that the house is now bottling a percentage of production in large-format bottles for the first time. It has also implemented a ten-year plan for the restoration of the winery and vineyards. The restoration of older vintages, recorking, and topping up will continue.

Biondi-Santi might be one of the estates in the region where the Riserva really is a step up on the “standard.” It should be the case with all Brunello, but I am not certain it is always so. The style of Brunello just seems to work in its “normal” form. Riservas can sometimes seem overwrought and even a little tired. The delightful freshness of the “standard” Brunellos is a large part of their charm.

So what can one expect? The 2010 was in glorious form, but in all honesty a lunch among mates does not always provide the most optimal tasting conditions.

Expect these wines to age magnificently, perhaps better than any other Sangiovese on the planet. We are talking decades, not just years. These are not blockbuster wines. If massive Barossa Shiraz is your thing (and no reason it shouldn’t be), you might be a touch underwhelmed by Biondi-Santi. Expect austerity rather than richness. Elegance, balance, finesse, grace, class, and refinement. And, of course, ever-increasing complexity.

The “standard,” also called the Annata, is from vines – all estate, of course – that range between ten and 25 years in general. Fermentation is in concrete vats and then three years in Slavonian oak, followed by a further year in bottle. The Riserva comes from vines in excess of 25 years of age. Fermentation here is in Slavonian oak barrels, again for three years followed by a further two years in bottle before release. The estate would expect a good Riserva to be able to age well for up to 80 years, perhaps longer.

If all this sounds like it might be too hard – after all, who among us buys wines we plan on drinking at the turn of the next century? – be assured that their balance and finesse make these wines utterly approachable in their youth. They are pretty much drink-anytime wines.

Experts will argue which are the great vintages, which says to me that the decisions are being made by way of personal preference because the wines are simply good across the board. The 1891 has long been legendary, but if we are honest that is purely academic for almost all of us. The 1955 is another legend as has been mentioned; 1964 and 1971 are both revered. Another source named 2010, 2001, 2006, and 2004 in descending order of preference as recent great years. The 2012 is certainly universally admired; ’13 a little less so, but it has many supporters.

Flavors will vary but florals, cherries, tobacco leaf, brambles, spices, new leather, red fruits, and more are all likely to be present in varying degrees. There will be vibrant acidity to carry the wine.

Biondi-Santi is one of the world’s great wine estates, one with an extraordinary history. Without it, the Italian wine world would be very different. Now we can only hope the good doctors have a few more hidden in their cellars!

For more information, please visit www.biondisanti.it.

You may also enjoy:

Soldera Wines: Sensational Super Tuscans With A Hollywood-Worthy Backstory

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

the ’55 Riserva was an amazing wine, one of the greatest wines I’ve ever had. Nice post!

Thanks, Alfonso, much appreciated. You are a very fortunate man. Would have loved to have seen that wine.