by Ken Gargett

The best laid plans. I had intended this to be a thorough look at Châteauneuf-du-Pape as I have tasted quite a few superb wines from that region of late, including some superstars. But I realized that would take a book. So then I thought I would restrict it to my two all-time favorites, Château Rayas and Henri Bonneau, but even that seemed extreme and surely they each deserve a piece on their own. So Henri Bonneau it is.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape in France

It was actually Château Rayas that led me to Henri Bonneau in a convoluted sort of way.

Around 20 years ago, several of us were invited to Champagne. I had done a fair bit of traveling with one of the guys so we decided to spend the week or so prior to Champagne visiting vineyards and wineries in other regions. We had not done the Rhône so it seemed ideal.

Château Rayas is a legendary producer, though also well known as perhaps the most eccentric of all. There are stories of the winemaker hiding under leaves to avoid meetings with visiting journalists and even tales of shotguns used to drive off unwanted guests.

We had an invitation, but we were still a little nervous. More so when we knew we were within the proverbial stone’s throw of the place but could not find it, no matter how hard we looked. There are no signs and they don’t give out telephone numbers. So, this being a time before the use of GPS navigation was common, we had to ring our contact back in Australia, wake him up, get him to ring the winery for directions, and then ring us back with those directions.

It turned out that we were literally 50 meters from the entrance.

When we visited, it was only a few years after the death of the previous maker, the legendary Jacques Reynaud. His nephew Emmanuel was now in charge. True to family form, the nephew had ducked out just before we arrived and would not be back for 90 minutes. Château Rayas is truly such a legendary producer, we were happy to wait. It was a wonderful visit in the end, though I remember our host being completely baffled as to why a couple of blokes from Australia wanted to visit him. He had taken off not to avoid us, but because he thought that someone was playing a prank, scheduling guests from Down Under.

Later that evening at a local café, we were chatting with the young sommelier, who was keen to know where we’d been. When we mentioned Château Rayas, he was stunned. He told us he’d been working in the region for several years and had often tried to get an appointment, to no avail. So on one occasion he simply turned up. Next thing he knew, a shotgun had apparently come out of a window and was firing at him. He’d hotfooted it out of there and has never gone back, he told us. So perhaps not an urban myth after all.

He said to us that if we liked Château Rayas, we should try Henri Bonneau.

I’ll be honest: even though we were both keen wine lovers and had tasted and read widely, at that time neither of us had heard of Henri Bonneau. In fairness, in those days not many had other than very serious Rhône freaks. There are even suggestions that for a long while Henri was keen to retain anonymity but was finally outed by critics who failed to respect those wishes.

No idea if that is true, but what is not in doubt is that the man must have been a real character. I don’t think I found a reference to him anywhere without mention of his mischievous nature, sense of humor, eccentricities, and full-on personality. A fan of Joan of Arc but apparently definitely not of Napoleon Bonaparte, for example (mentioning this earned journalist John Livingstone-Learmonth a ban from the cellar). He was always keen to share his views on the Algerian War (in 1958 and 1959, he’d served as a regimental cook in that war – his other 75 years were lived in that same house in the village where he was born) and on the shortcomings of bureaucrats.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape region

In his Rhône Renaissance, Remington Norman relates how the conversation bounces from appellation rules to the decline of civilization. His favorite dish was apparently beef testicles, bought by the bucket from the local slaughterhouse.

Our friendly somm gave us a quick rundown and suggested we try the one bottle of Henri Bonneau he had on his list. From his rundown, we knew that this was his third-level wine (the actual ranking is a slightly curious and flexible thing), and I knew that it came from a very ordinary vintage. Not to mention it was probably the most expensive wine on his list.

The cynic in me wondered if we were convenient patsies for our friend to offload overpriced rubbish, and that is an uncharitable thought for which I should ever remain ashamed: the wine blew us away. All I could think was that if this is a third-level wine from a poor year, what on earth is the good stuff like. That and was it available in Australia?

We were both keen to visit but unfortunately (okay, “unfortunate” is definitely not the right word but you know what I mean) we had appointments the following day at some of Burgundy’s finest producers, so there was no time. And I suspect it would have been another of those estates nearly impossible to find – I gather they operate out of cellars near the family home in the middle of the village – nor do they accept walk-in visitors. But as soon as I returned home, I made enquiries.

It turned out one of my oldest mates was the importer. He’d just never mentioned the wines because he never had any interest from anyone, and the stocks were extremely limited. They were a lot more limited after I jumped on what I could. I have tried to pick up bottles over the years, but they are very rare and have become seriously expensive (although not as expensive as many comparable estates from other regions), especially since Henri passed away in 2016 at 77. At that time, there were grave concerns about whether the estate would continue, but apparently Henri’s son, Marcel, had been working with him for some years and has picked up the torch (also working with Henri’s commercial partner).

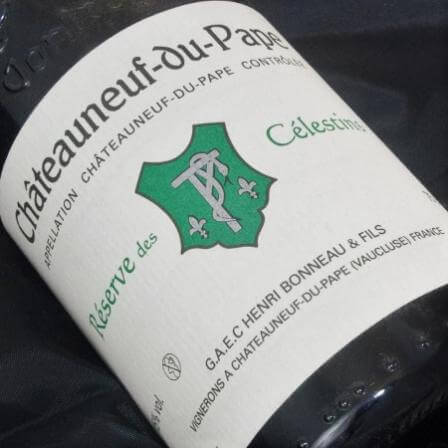

A recent Châteauneuf-du-Pape lunch saw three of us arrive with different bottles of Henri Bonneau. All were spectacular: an ’03 Châteauneuf, the ’08 Celestins, and mine, an older Celestins (I’ll get to the different wines in the portfolio in a moment). I say older as this was the ultimate blind wine. The small label with the vintage had slipped away and Henri Bonneau does not put the vintage on the cork, so just which vintage remained a mystery, but I suspect possibly 1998 or early this millennium. The two Celestins battled for wine of the day with another superb Châteauneuf, the Pegau Cuvée Da Capo 2007, a legendary wine that attracted perfect scores in its youth and has only got better (Henri Bonneau and Paul Feraud of Domaine du Pegau went to school together).

A drawing of Châteauneuf-du-Pape in the 17th century

A short history of Henri Bonneau

The Henri Bonneau property has been in operation for several centuries – some suggest that the vineyards were first planted in 1667 – but it was only in 1927 that Henri’s father (who in all my searches and old books on the Rhône in my library is only ever noted as Henri’s father and never named; my guess is he would be Marcel as it does seem that almost every Bonneau other than Henri is so dubbed) began estate bottling. Henri, born in 1938, was the twelfth-generation winemaker.

Henri Bonneau’s vines are “possibly” older than most in the region, and Grenache is heavily favored. As to whether Henri Bonneau prefers older or younger vines depends on the source of information one uses – they vary, though most suggest Henri liked vines around 30 years of age.

Château Rayas is famously 100 percent Grenache in a region where some 13 varieties are available for inclusion and where blends are seemingly de rigueur. The question often asked, even assumed, is whether or not Henri Bonneau is also 100 percent Grenache. The answer is no, around 80 percent of the vineyards is Grenache, but it was clearly his preferred option.

John Livingstone-Learmonth’s Wines of the Rhône (revised in 1992) declares that Henri Bonneau is a traditionalist and that he is against “the Syrah,” insisting “It all boils down to the Grenache” and considered grapes like Mourvèdre, Cinsault, Clairette, Counoise, Vaccarèse, and a little Syrah as “just like the salt and pepper in the soup.”

Others suggest that there is absolutely no Syrah in the vineyards and I suspect that this might be accurate. Harry Karis in his The Châteauneuf-du-Pape Wine Book says that Henri actually disliked Syrah. Whenever he was asked about the percentages of the varieties in his wine, he simply dismissed the question. If pushed, he’d concede his wines were at least 90 percent Grenache.

The estate has 5.25 hectares near the village of Châteauneuf, including in the famous Le Crau Lieu-dit, and another at Grand Pierre nestled against Château Rayas itself, a vineyard sometimes declared to be even greater than that of Rayas. Sites in Châteauneuf don’t come much more highly regarded. There is another, lesser, and stonier site of 0.75 hectares near Courthezon, which is largely used for the Cuvée Marie Beurrier. Together, they form 13 plots.

Henri Bonneau Châteauneuf-du-Pape Cuvée Marie Beurrier (photo courtesy Sotheby’s)

Cuvée Marie Beurrier is named after Henri’s wife’s aunt, who was apparently a superb cook, and Henri was well known for his love of good food. Cuvée Marie Beurrier is usually a richly flavored, dense, complex wine with black fruits, meaty notes and even a touch of pepper. It has been described as Henri Bonneau’s La Tâche to his Romanée-Conti (the Celestins). Praise does not come much higher than that.

I’ve visited cellars that are cleaner than any hospital you’d find – Alvaro Palacios in Priorat springs to mind – but occasionally you come across those that are anything but. Tales abound of damp, cold cellars in Burgundy, wiping mold and cobwebs off bottles. Places like Clos Mogador and Château Rayas both make my place look like a neatness museum – an achievement many would have thought impossible. Apparently, the cellars at Henri Bonneau fall very much into the “not tidy” category. I’m sure I’d feel at home.

De-stalking occurs only in very poor years. The varieties are co-fermented over two to three weeks, as a generalization, in open concrete fermenters, with regular pumpovers. First press is added, and the wine spends time in a mix of different-sized older oak, including an old beer barrel from Burgundy.

There is no oak in the cellar younger than at least a decade. Traditionally, the wines spend about 30 months in the old oak (bottling is when the estate believes the wine is ready – so the 2006 Cuvée Marie Beurrier was still sitting in oak, well after the 2006 Celestins was in bottle). Fining is done with half a dozen egg whites per barrel. Nothing is filtered. One suspects that the selection of which barrel and what size for the wines is more about what is convenient and available than any scientific choice.

Henri has been quoted saying that he never bottled more than half the wine he produced in any vintage and has been known not to bottle any in some vintages (1982, for example). He was not fussed about good, bad, or indifferent vintages. He would assess the wine he made and if it was not up to his standard, he did not release it.

Henri Bonneau wines

Henri Bonneau’s first vintage was 1956, perhaps the worst of the lot, so bad vintages are not something that have ever bothered the estate. In addition, the wines are only released when they are believed ready, a policy that many others could consider. It meant that, for example, the horrendously hot vintage of 2003 was not considered to suit the style of Celestins, but Henri Bonneau did make a Marie Beurrier, which has proved superb. All the fruit that usually went into Celestins went to the Marie Beurrier in 2003.

Henri Bonneau Châteauneuf-du-Pape Celestins

Having tasted that wine several times, including recently, it is undoubtedly a wine that exceeds the vintage. I can only imagine this is because a good Celestins (and isn’t that a prime example of tautology) is a beautifully elegant wine and the fruit providing that elegance seems to have balanced the richer Marie Beurrier style. It works.

The “standard” is the Châteauneuf-du-Pape, which Henri considered “good.” The Cuvée Marie Beurrier he saw as the next level up, while it is his Reserve des Celestins that is his “grand vin.”

It was originally called Clos des Celestins and was registered as a brand at 9:00 am on January 31, 1927 (quite why that should be so important as to be quoted in information available is beyond me, although possibly it is relevant as the estate was one of the first to “estate bottle” and this began in 1927).

Henri-Bonneau Châteauneuf-du-Pape _Celestins

With Celestins, a wine created from barrel selection rather than any specific plot, expect herbs, minerals, florals, black fruits, complexity, and finesse. From a region not exactly known for elegance, this wine nails it. And yet there is no question that these are rich and powerful wines. How they manage to walk that tightrope is a mystery that I am certain many other makers would love to unlock. This is also a wine that will improve in the cellar for years, if not decades. But you can say this about all the Henri Bonneau wines.

There are two other wines.

Les Rouliers is a non-vintage blend and because of that so often dismissed – anything made by this estate should be on any wine lover’s radar, even if bureaucracy and regulations deem it to be the lowest of the low. Usually a combination of two vintages, it comes from a vineyard on the other side of the Rhône River in the Gard, which was worked by Marcel, and sometimes included leftover fruit from the main vineyards. It is said to be around 80 percent Grenache and 20 percent Cinsault. Fresh, complex, and yet able to age impressively as has been said before, there would be plenty of winemakers in the region proud to call this their top wine.

The other is a wine Henri made twice, in 1990 and 1998, called Cuvée Speciale (there are some suggestions the estate made one in 2007 but I can find nothing to corroborate that). Those are two great years in the region but there have been plenty since and they have not made the wine again. It is an undoubtedly controversial wine. I have tasted all of their other wines but never this one. That said, I do have a bottle in the cellar but unfortunately, again, the label has disappeared, and I have no idea which bottle it might be. One day, I’ll start taking some chances.

If I have one complaint about Henri Bonneau wines: use better glue on the labels!!

Cuvée Speciale is from grapes picked a little later than most (Henri Bonneau has always preferred a later harvest in general). It has a higher level of alcohol and apparently also exhibits residual sweetness. Curious. All that said, these wines bring huge prices at auction, around twice that achieved by Celestins despite that being the better wine by all reports. Apparently, the reason these two port-like wines were released was that they were barrels destined for Celestins that refused to fully ferment.

Total production does not exceed 16,000 bottles per annum (other sources suggest as many as 25,000, but even that is miniscule in world terms). Certainly not much for a world that is seeking great wine.

I could dig out old tasting notes on a number of Henri Bonneau wines from across the years, but I’m not sure how useful that might be. Perhaps suffice to say that Henri Bonneau is not only one of the great Rhône producers, but among the elite from around the globe. Never ever miss a chance to try these wines, at any level.

The legend may no longer be with us, but the wines live on.

You may also enjoy:

The Up-Down-And-Up-Again Wines Of Bouchard Père & Fils In Burgundy

Château Pontet-Canet Bordeaux: A ‘Super Second’ Wine Story

The World’s Best Wine? No Contest: Romanée-Conti By Domaine De La Romanée-Conti

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!