Foradori: Exciting Local Grape Varieties From Trentino, Italy

by Ken Gargett

It has been suggested on more than one occasion that when my long-term wine friends get together, it looks more like a remake of Cocoon than a wine tasting. Grumpy Old Men or even Jurassic Park seems more appropriate.

Some of these guys have truly extraordinary cellars and a great knowledge of wine, but they are perhaps a smidge traditional. I remember years ago, one of our number emphatically declaring that he had no interest in Italian wine. More than enough good wines from France (plus his beloved Ports and German Rieslings) without having to worry about some fancy new region. He was always a touch extreme, but for more than a few of the guys, certainly not all, even Burgundy is a bit of an upstart region. Bordeaux rules – always has and always will – and everything else follows.

I am half a generation younger than many of the guys, which means I was never quite so tied to tradition, though it did mean I missed many of the years when great wine was barely more expensive than soft drinks (hence, my friends’ extraordinary cellars). I have made it my mission to try and open a few eyes to exciting new regions and wines, and to be fair the guys are usually open to this. They are, however, notoriously hard to impress – a good thing.

Some time ago, I was watching a wine TV show, something I rarely do as I don’t think wine translates to television particularly well. This was one I did enjoy. In this episode, the presenters, two actors, had traveled to the northern reaches of Italy, a place I had only visited on a skiing holiday rather than for wine – and as much as I loved the place, my skiing has never been much more than finding new ways to tumble down mountains. But even that was great fun in waist-deep powder snow. The television guys were blown away by the spectacular location of the vineyards, the methods in use, and the wines. And on this occasion, television managed to convey this perfectly.

Harvest time at the Foradori winery in Italy

The winery is Foradori based in Trentino, and I’ll get to it shortly. First, I needed to find out more, especially if the wines were brought into Australia. As it happened, a local importer in Brisbane (Addley Clark Fine Wines), run by an old mate of mine, is the Australian agent. What chance of getting hold of some? Despite these wines being heavily allocated, he kindly allowed me a set. I thought that this was a perfect opportunity to introduce the guys to some really exciting new wines.

The best laid plans . . .

Along came COVID-19, border closures (with me on the wrong side of home for six months), and a raft of other issues. My plans fell into disarray.

Lemons into lemonade? A year passed and a new set of releases was available, so I thought I’d give it another go and this time with both sets of wines. What could go wrong?

The tasting? A mixed response would be the best way to describe it. We were behind the proverbial eight ball from the start. I had decided to do the event completely blind, not even mentioning the winery or region, figuring that to do so would invite inevitable and most likely unflattering preconceptions.

Sadly, it was the middle of flu season Down Under, a severe one, and several of the troops were struggling. For some reason, the guys had convinced themselves (despite all my advice to the contrary) that they would be enjoying a large tasting of First Growth Bordeaux or Grand Cru Burgundy. For others, the idea of biodynamic or natural winemaking is akin to witchcraft and about as welcome as a Supreme Court justice at an unmarried mothers’ convention. Indigenous varieties? Unheard-of grapes? I should have known better. The wines did not convert my friends.

Personally, I thought that harsh (and pretty much all reviewers I have found would agree), but fair enough. Part of the joy of wine is that different styles, varieties, and regions appeal to different people.

Foradori vineyards in the Italian Dolomites

History of Foradori

The original winery was established in 1901, but it was 1939 before the Foradori family was involved when Vittorio Foradori purchased the place. In 1960, his son, Roberto, began working there and the first vintage of Foradori was released. Roberto passed away in 1976 and his widow, Gabriella, took over. In 1985, at just 20, daughter Elisabetta stepped in after completing her wine studies at the Istituto di San Michele all’Adige. This is where our story begins – revolutionary, rather than evolutionary.

Mass selections with the local variety, Teroldego, began the following year. The year after that, the flagship wine Granato was first made. It seems that every year after that for some time, a new wine would join the portfolio, while others dropped from sight.

In 2002, the conversion to biodynamics began and certification was achieved in 2009. Two thousand twelve saw Elisabetta’s son, Emilio, now the winemaker, work his first vintage. Sadly, Elisabetta’s husband, Rainer Zierock, passed away in February 2009. Emilio’s brother Theo joined in 2015. In recent years, the estate has diversified into vegetable production (thanks to daughter Myrtha) and cheesemaking. It is this fourth generation now in control today.

The estate’s philosophy is detailed extensively on its website, which is definitely worth reading for those interested in biodynamics, but perhaps can be neatly summed up in the statement, “It is our duty and privilege to wake up every morning and to be free to work according to the message that the earth conveys to us in that moment. We work surrounded by mountains, cultivating Teroldego and Pinot Grigio on alluvial soils of the Campo Rotaliano, Nosiola, and Manzoni Bianco on the calcareous-clayey hills of Cognola.” They see themselves as guardians of their land.

The estate has 30 hectares of vineyards – 80 percent Teroldego, 10 percent Manzoni Bianco, 5 percent Nosiola, and 5 percent Pinot Grigio – 80 which provides an average production of around 180,000 bottles annually; 100,000 of these are split between the Foradori and Lezer, two wines I didn’t include in the tasting.

For anyone who has not seen the Dolomites, it should be very high on your bucket list, a truly spectacular area. This is in the Veneto, Trentino-Alto Adige and Friuli-Venezia Giulia part of the world, a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2009 and one with an extraordinary history of winemaking dating back centuries, though it was around the fifteenth century before wine was able to compete with olive oil in importance.

In 1709, catastrophically severe frosts caused such damage that everything changed. There was a move to varieties more able to withstand the cold, but then, in the nineteenth century a medley of viticultural diseases descended on the region: downy mildew, powdery mildew, and phylloxera.

This led to the use of the international/non-native varieties, though in some places the traditional varieties such as Teroldego, Marzemino, and Nosiola survived. It was only last century that we saw an increase in interest in wines from the Trentino region, but issues not restricted to Trentino by any means of proliferate viticulture with demeaningly high yields, mechanization, the use of chemicals, and the continued spread of international grapes at the expense of the native varieties did nothing to improve the region’s reputation.

Fortunately, a few smaller operations such as Foradori have maintained the faith, working with the local varieties and doing so in ecologically sustainable ways, resulting in wines of character, interest, and representing the local terroir.

Biodynamics

Biodynamics has long been controversial. As I have touched on previously, it is basically a system of agriculture that incorporates biological and cosmic factors. To call it a step beyond organic farming is a gross simplification. That it was developed by Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian architect, social reformer, occultist, esotericist, and possible clairvoyant, is usually overlooked by its adherents. Although that may be completely irrelevant to his inadvertent contributions to viticulture (he was also apparently a teetotaler).

Some see biodynamics as little more than howling at the moon. Others as a way to ensure life in the soils, a return to sustainability, and a way to ensure the best possible fruit. Some call it spiritual scientific viticulture/research. Personally, I think anything that improves the health of soil for viticulture (or any form of agriculture) must surely be a good thing. That said, burying cow horns and the use of lunar cycles may push the boundaries for some.

The difficulty comes when we look at many of the best wine estates on the planet and the fact that they use biodynamics (or BD as it is often called): Louis Roederer, Pontet-Canet, Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, Cullen’s, Seña, Felton Road, Château Palmer, Domaine Leflaive, Burklin-Wolf, Domaine Weinbach, Zind-Humbrecht, Climens, Rippon, Yangarra, William Downie, and so many more.

But it is chicken and egg stuff. Pretty much all of these estates were making superb wines before they moved to BD. So it is not possible to say that they are great makers because of BD alone. What this does say to me is that if so many of the world’s best believe in BD, then clearly it cannot be discounted.

Some people still struggle to get past what they see as the fruit bat aspects of BD. A statement on the Foradori site saying, “Through limestone the so-called inner planets Moon, Mercury, and Venus drive man and nature, while through silica we gain guidance from outer planets Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn” will do nothing to appease their concerns. Just as it is a case of “each to their own” when it comes to preferred wines, so too does that apply to the methods used to create those wines.

Cow grazing in the Foradori vineyards

Foradori states, “To farm biodynamically does not mean to farm mechanically with a fixed method, nor does it mean to fantasize in pseudo-religious beliefs. Instead, to farm biodynamically means to apply universal principles, ideas, thoughts and feelings, depending on the circumstances, the conditions, and the problems one is confronted with at the time on the field and respecting the originality and freedom of those who apply this method.” Which is all very well but I am not sure it says much. Still, as ever, the proof is in the pudding – or in this case, the bottle.

The estate runs half a dozen Tyrolean Grey cows in the vineyards, which contribute milk, meat, and fertilizer with their manure combined with various organic matter collected from the vineyard and winery.

The Foradori winery and wines

As mentioned above, the team works in two sub-regions. Campo Rotaliano is located on the border between Trentino and Alto Adige, a flood plain formed by the Noce and Adige Rivers. It forms a 400-hectare triangle surrounded by the local cliffs. There are records attesting to its greatness as a viticultural region as far back as 1231, though there is no mention of the Teroldego grape here until 1540-1542. The earliest mention of Teroldego in general is in 1383, grown in fields between Trento and Povo.

Trentino received DOC status in 1971, though some felt that the opportunity to offer top-quality wines across the region was squandered at the altar of higher yields.

Fontanasanta is an estate with an illustrious history surrounded by streams and dense forests. Once largely a hunting park, vineyards and fruit trees were established and it was rented by the Foradori team in 2007 as it was ideal for growing Manzoni and Nosiola. They have brought in three Grigio Alpine cows, a local breed, to help bring life back to the estate. As elsewhere, they work biodynamically to ensure they work with, and not against, nature.

Turning to the wines, we tasted two vintages of each of the following: the Pinot Grigio from Fuoripista, the gravelly vineyard near the Noce River on the southern edge of Campo Rotaliano; Manzoni Bianco and Nosiola from Fontanasanta; and Teroldego, single vineyards called Morei and Sgarzon as well as the Reserve Teroldego the estate calls Granato. All were from the 2019 and 2020 vintages with the exception of the Granato, which came from 2018 and 2019 as it is held back for an extra year in comparison with the other wines.

But first, a quick word on vintages. Two thousand eighteen was considered satisfactory, better for reds than whites; 2019 was warm and balanced and yet still exhibited some bright acidity; and 2020 was another warm year, good but perhaps not absolutely top shelf. For those looking to the future, early reports suggest 2021 will top them all.

The Pinot Grigio (Foradori’s Fuoripista Pinot Grigio – Vigneti delle Dolomiti IGT, as are all of these wines) is actually a collaboration between Foradori and another biodynamic winemaker, Marco Devigili from Campo Rotaliano. The wine spends more than eight months on skins inside Tinajas (amphorae) brought from Spain. The estate considers that the extended period in the tinaja “makes it brighter and more delicate.” For Elisabetta, the amphorae “multiply the message.”

Wine-filled Tinajas (amphorae) in the Foradori cellar

Mention amphorae and the assumption is that we are down the natural wine rabbit hole. Foradori seems to prefer not to see its wines in that light. To be honest, far too many natural wines are nearly undrinkable. Claiming minimal or no intervention might work well with the trendy, manbun, hipster, insta-everything-you’ve-ever-eaten crowd but it doesn’t necessarily make them good wines. There is a reason that winemakers do intervene when necessary, and plenty of these natural wines could have done with a little. Of course, that does not mean that there are not some impressive wines that fall into that category.

Wine-filled Tinajas (amphorae) in the Foradori cellar

To be honest, and I accept that this might mean I’ll have to turn in my black turtlenecks and be banned from drinking cloudy, dodgy wines, but I always find the claims of no intervention a little disingenuous. Native vegetation has been removed, vines planted and harvested, the grapes put into receptacles of whatever sort, sulfur usually added even if only in tiny amounts, and then bottled. All of that is intervention. Claims of minimal intervention I can live with. No intervention? It is a nice sentiment, but it is what my grandmother would have called telling porkies. But no matter as long as the wine is good.

The Pinot Grigio comes from two hectares at Campo Rotaliano and has an annual production of some 10,000 bottles.

Foradori Pinot Grigio

Of all the wines, this was certainly an eye-opener. The color was an obvious orange for both the 2019 and 2020. The aromas for both wines were gorgeous, exotic, exuberant, yet the palate was very quiet, almost muted, the complete anthesis of the nose. Some complexity and bright spices. Twenty twenty was the pick for me.

The Foradori Fontanasanta Manzoni Bianco is a local variety that I am willing to wager is unfamiliar to most of us – it certainly was to me (as was the Nosiola and Teroldego). Grown on clay/limestone soils in a five-hectare vineyard at Fontanasanta, fermentation takes place on skins in cement tanks, and is followed by seven months of aging in acacia casks. Production is 20,000 bottles per annum.

Foradori Fontanasanta Manzoni Bianco

Ian d’Agata’s indispensable tome on Italian varieties, Native Wine Grapes of Italy, provides insight into Manzoni Bianco. It is a crossing, the most successful of a program of attempts, in this case between Riesling and Pinot Bianco, developed back in the 1920s. D’Agata describes it as, “Extremely high quality . . . one of the world’s few truly successful crossings.” The estate sees this as a wine that “really comes into its own at least three years after harvest.” It gives the “deeply mineral character” of the Riesling and the “floral scent of Pinot Blanc.”

Both vintages exhibited perfumes and nuts with citrus/lemon touches. Fresh and clean, the 2020 showed a little more complexity. Really interesting stuff.

The Foradori Fontanasanta Nosiola comes from three hectares of calcareous clay. The wine follows fermentation with eight months on skins in tinajas. Production is 10,000 bottles per annum.

Foradori Fontanasanta Nosiola

Nosiola is an ancient Trentino grape, the only white grape variety native to the region, and far less widespread than it once was, restricted to a few small areas. The wines are considered to offer both delicacy and longevity.

D’Agata links the name to hazelnuts, as most do, and describes it as a “pleasant dry white wine of crisp, concentrated lemony zip,” but notes that it can make some of the “world’s greatest sweet wines” in the form of Vin Santo. It was usually used as a blending component until the early 1970s.

Both vintages exhibited the typical hazelnut characters, with peach notes in the 2019 and more lemon and apple-y hints in the 2020, which has serious length. Both have floral notes and impress with their length. Wines for the future, indeed. Intense and appealing, there was little to pick between the two vintages.

If we move to Teroldego, Foradori offers three versions.

D’Agata notes Teroldego as the most important red for Trentino. He acknowledges other international and local varieties but, as he says, “Teroldego rules.” In “DNA” terms, Teroldego is the “uncle” of Syrah/Shiraz and also has links to Pinot Noir – not an unimpressive family tree. He acknowledges Elisabetta Foradori as the world’s greatest producer of this grape. Its typical characters are fruit-strong with cherries, tar, and herbs through to soft tannins. Once largely sold off in bulk, it now produces “truly important, age-worthy wines.”

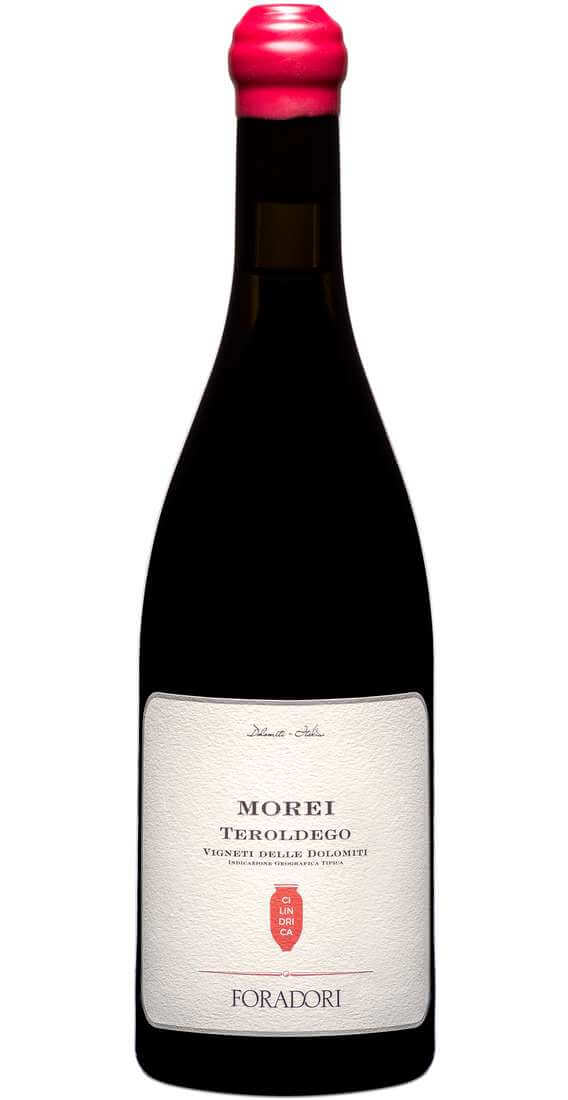

Foradori Morei Teroldego

The Foradori Teroldego Morei is from the 2.5-hectare Morei vineyard at Campo Rotaliano, based on alluvial, pebbly soil. Fermentation is in amphorae, and the wine then spends eight months on skins. Production is 10,000 bottles per annum.

Morei means “dark” in the local dialect and this can be seen in the grapes. These are wines with “a texture of minerality and density.”

For me, there was a greater gap between the two vintages of the Morei than any of the other wines. The 2020 shone with spices, chocolate notes, herbs, and aniseed. Excellent length and a fine future. The 2019, on the other hand, had little to offer. Rustic, earthy, broad, and rather unexciting, it was the least impressive wine of the day. From a little research, it seems I am not alone in thinking this.

The Foradori Sgarzon Teroldego hails from a discrete vineyard, 2.5 hectares of alluvial sandy soil, in the Campo Rotaliano. Again, fermentation, followed by eight months on skins in amphorae. Production is 10,000 bottles per annum. Sgarzon means “shoot” in the local dialect – I am assuming that is shoot as in a plant shooting rather than anything to do with firearms.

The two vintages both excited. The 2019, my preference by a whisker, offered black cherries, chocolate, cloves, blackberries, and coffee beans. Seamless with great length. This is a cracking wine. The 2020 is more mulberries, vegemite, soy, and dark berries. Again, excellent length. Both have a great future, and both have an alluring freshness. Of the two single vineyard wines, Sgarzon is my pick.

Finally, the Foradori Granato – 100 percent Teroldego, the flagship. It comes from three separate sites in the Campo Rotaliano totaling four hectares, soils varying across alluvial, gravel, and pebble. The vineyards are set up with pergolas. Fermentation takes place in large open vats, followed by 15 months in large casks. Production is 20,000 bottles per annum. The vines are around 70 years of age. The name Granato links the wine to pomegranates as this variety is often grown alongside that fruit.

Elisabetta is seen by many as the savior of Teroldego, which is now grown in other regions of Italy and further afield (supposedly some in Australia, though I’ve never seen any). She worked on mass selection and has registered 15 different clones (it seems a bit Pinot-like in that), though she apparently prefers to work with massal selections (new nursery vines). She has even grown some from seed – for a plant, that might not seem like big news, but it is very rare for vineyards.

The Tinajas, almost 200 of them, range in size from 350 liters to twice that. The wines all see wild fermentation and include varying levels of stems. Sulfur use has been reduced, and with all that the wines became fresh and exciting.

The style of Granato has changed over the years. In the early days, it was “international,” aged in new French barriques but new oak stopped with the 2000 and barriques from 2008.

Foradori vineyards

The move to biodynamics played its role. Hand-picked fruit is partly destemmed and gently pressed. Foradori uses approximately 40-50 percent whole bunches. Fermentation takes place in large open wooden vats with very little sulfur. Maceration takes two to three weeks. The team does not punch down or pump over, but works with submerged caps. The wine will then be aged in old botti, up to 22 hectoliters, for 15 months. There is no filtering.

For me, there is not a struck match between the two vintages in quality. Two superb wines. Twenty nineteen is seamless, complex, complete, and finely layered with dark berries, aniseed, black olives, and cassis. Expect it to age and improve over many years.

The 2020 may have even greater length, again with the black cherry notes, licorice, chocolate, and beef stock. Plush and soft tannins on that wonderfully long finish. Drink these wines any time over the next decade or two.

Foradori may not be everyone’s cup of tea (and I won’t be wasting any more of mine on my old mates), but these are exciting, quality wines showcasing local varieties. They deserve attention.

For more information, please visit www.agricolaforadori.com.

You may also enjoy:

Soldera Wines: Sensational Super Tuscans With A Hollywood-Worthy Backstory

Barale Fratelli Barolo Chinato: Difficult To Find, But Well Worth The Search

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!