Graham’s Single Harvest Tawny Port Wines In The Cellar Master’s Trilogy

by Ken Gargett

Oporto, in the north of Portugal, is one of my favorite cities in all the world. Not just as home to their truly extraordinary wines, but a must visit nestled on the Douro River.

Looking from Porto across the Douro river to the Port houses in Vila Nova de Gaia

If you are lucky, those fabulous rabelo boats might be out in force on the river, the flat-bottomed sailing boats that have transported people and, more importantly, barrels of Port for decades. Those who love a good train trip must do the scenic ride up to Pinhão in the Douro Valley, one of the world’s most spectacular wine regions. The train hugs the river for most of the trip.

Back in Oporto (or Porto, the name of this gorgeous city seems interchangeable), in addition to the Port houses there is an increasingly exciting restaurant scene and great accommodation.

Graham’s Quinta dos Malvedos vineyards above the Douro river in northern Portugal

My first visit was many years ago when working in London. I managed to get a spot with the English Law Society cricket team on its annual tour, which happened to be to Oporto. I have loved the place ever since and been back a number of times, though always with wine in mind on subsequent visits.

It has not always gone as smoothly. One trip a few years ago started with the plane from Madrid delayed about eight hours and then rerouted to a town in northwest Spain. Mishaps with luggage followed before a pile of unhappy strangers piled onto the bus to be driven to Oporto. The bus went literally four feet, not even out of the airport, before it had its first accident, and, trust me, a car accident in Spain or Portugal is an occasion for everyone within three miles to come and give an opinion.

The bus eventually headed off but immediately developed engine troubles. So we limped along for several hours at around a top speed of 50 kmh. If I tell you that the best-behaved person on the bus was the screaming three-month-old child, you’ll get the picture of what fun that was. And we were then unceremoniously dumped many miles from the intended arrival destination, and many miles from those collecting me. But what would travel be without the occasional unplanned adventure?

Port wines

Port comes in various guises. Vintage Port, which I have looked at on several occasions, is usually considered the pinnacle, but the great tawnies should never be neglected.

The Douro river in northern Portugal

In general, port is made from a range of varieties that are grown in the designated region of the Douro Valley. The fermentation is stopped by the addition of spirits, which leaves varying levels of residual sweetness and increases the alcohol level above that of table wines. The barrels are usually then moved to Vila Nova de Gaia, basically part of Oporto these days, located on the “other” side of the river.

The name Port comes, rather obviously, from the town. Official appellation dates back to 1796 – only Chianti (1716) and Tokaji (1730) are older.

The most basic style of Port is called Ruby, these days stored in either stainless steel or concrete and bottled after only a few years. Rubies tend to be fresh, simple, fruity, attractive drinking and are not intended for further aging. There are Reserve Rubies and Rosé Port.

White Ports are made – naturally – from white grapes and often find a home in cocktails or as a refreshing end to a meal. Sometimes as an aperitif, though I am not convinced they’ll ever replace champagne.

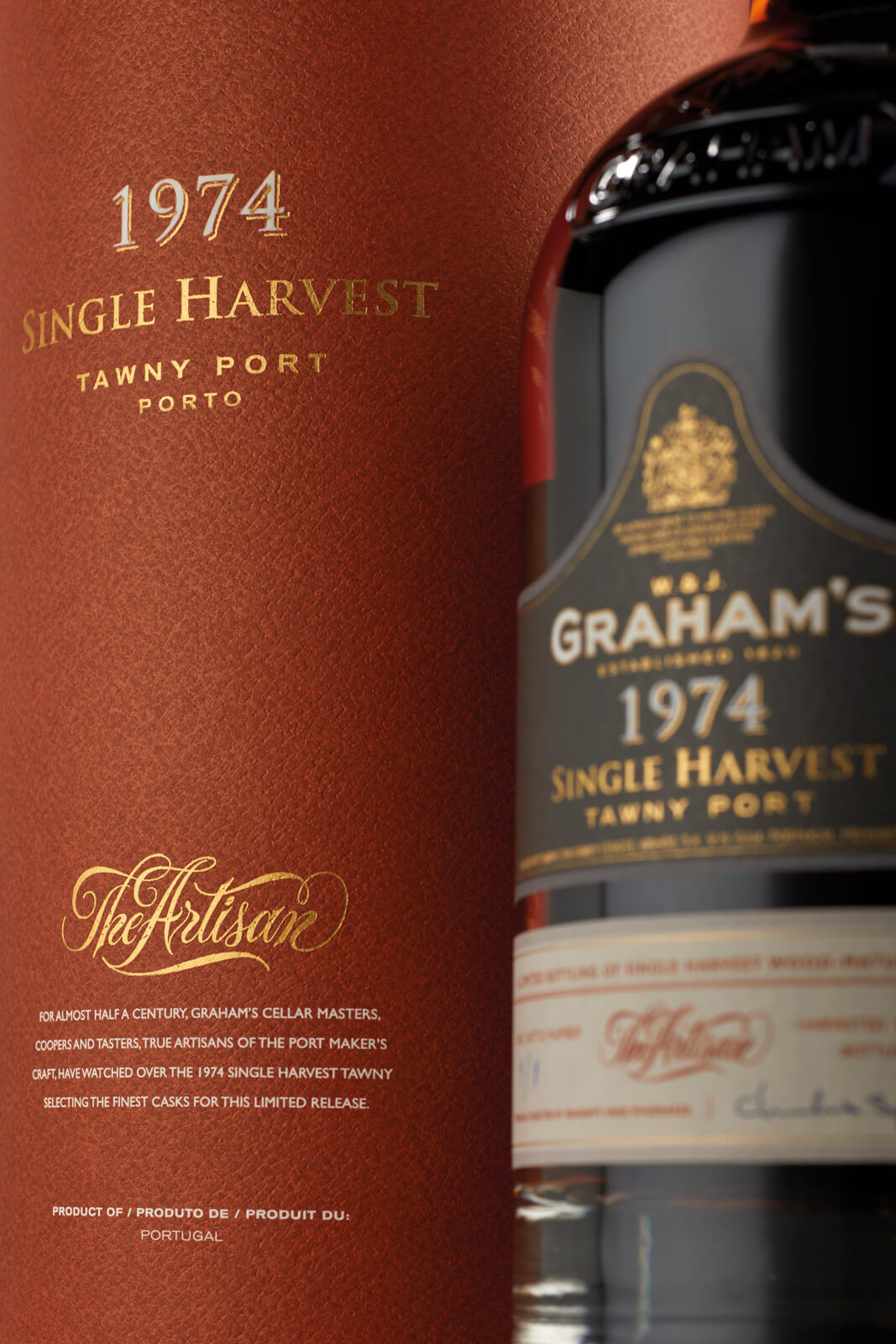

Graham’s 1974 Single Harvest Tawny The Artisan

Late Bottled Vintage Port (LBV) is at its most simplistic halfway between Tawny Port and Vintage Port. It developed as Port that was left in the barrel for longer than is usual for Vintage Port, but not as long as Tawny. LBVs are usually bottled around five or six years after the vintage and can be filtered or not. They will not be as complex or exciting as the better Vintage Ports but they can be aged for a further period of time, something that is usually not associated with Tawnies. Crusted Ports tend to be a mix of a few vintages, though they do not seem very common.

Vintage Port is only a very small percentage of production and only made in the best years. It is usual to only see a few vintages declared each decade, though recently we have been seeing more: the famous trio of 2016, 2017, and 2018 (not all declared by all producers, of course) is the first time in several hundred years where three consecutive vintages have been commonly declared.

It is made by premium grapes from a single vintage going into barrels for no more than two and a half years before bottling. Good examples can age and improve for many decades. Traditionally, Vintage Ports would not be opened for at least 10 or 20 years, though a combination of modern winemaking and the general lack of patience that afflicts the world these days often sees them opened in their infancy. Some consumers prefer that style.

Many houses will offer single-quinta Ports, which are basically Vintage Ports from years that have not been generally declared and sourced from single sites within the best vineyards.

Making oak barrels at Graham’s

Tawny Ports will have spent many years in barrels – this varies of course, depending on what the producer is after. They are released ready to drink and are not for future aging, at least not with the intention of further improvement. The better examples are given an indication of age – Graham’s, for example, offers a Ten-, Twenty-, Thirty-, and Forty-Year Tawny. These are blended from many different barrels from a number of vintages. It is a skill that equates to what we see in Champagne from the top chefs de cave.

Within the Tawny category, there are also Ports called Colheitas or Single Harvest Ports. These are Tawnies that have been aged for however many years in barrel, but are from a single vintage only. Some houses have barrels dating back many decades, and even longer, which they bottle as Colheita/Single Harvest (either name is acceptable).

Some years ago, the conventional wisdom had the “Portuguese Port houses” as the specialists for the Tawny styles and Colheitas, while the “British Port houses” were more aligned with the great Vintage Ports. These days, that line has very much blurred and great examples are available from both “sides.”

The difference is that although they are, of course, all Portuguese, we think of those with a Portuguese history as the “Portuguese Port houses” – names such as, perhaps most famously, Quinta do Noval in addition to Kopke, Burmeister, Cálem, Offley, Quinta de Crasto, Neipoort (these latter two both personal favorites), and Ferreira. Those with a “British” history are known as the “British Port houses” and include names such as Graham’s, Dows, Taylor’s, Croft, Cockburn’s, Churchill, and Warre’s. Plenty more in both categories.

On one visit some years ago, a few of us had arrived during a local Port exhibition. We were invited to a tasting of great Colheitas, and I have been a fan ever since. Cálem 1957, Burmeister 1944 and 1937, Barros 1935, and Kopke 1941, 1935 (a white Colheita), and the jewel in the crown, the Kopke 1900. Who wouldn’t fall in love with the style?

If I may digress, as we left we were approached by the organizers and asked if we’d like to return the following day as they were going to be “doing the old ones.” We had planned on leaving the next day but that was immediately shelved. The following day was Ferreira Vintage Ports: 1994, 1978, 1966, 1947 (magnums), 1917, and 1863. Extraordinary. Even more extraordinary was that the organizers had opened more bottles than needed so a small group of us got to sit around for several hours post the tasting, enjoying the various bottles. You wonder why I love Oporto so much!!

History of Graham’s

Graham’s is part of the Symington empire, along with houses/producers such as Dow’s, Warre’s, Cockburn’s, Quarles Harris, Martinez, Gould Campbell, Smith Woodhouse, and Quinta do Vesuvio. In other words, the Symington family is extraordinarily important in the world of Port.

Graham’s Quinta dos Malvedos vineyards above the Douro river in northern Portugal

The empire also owns a number of highly regarded table wine producers in the Douro and several of the great Madeira estates. Its holdings in the Douro include 27 quintas (a quinta basically being a vineyard estate), which total around 940 hectares of vineyards. The key quintas for Graham’s are Quinta dos Malvedos, Quinta do Tua, Quinta das Lages, Quinta da Vila Velha, and Quinta do Vale de Malhadas. The leading grape varieties in use are Touriga Franca, Tinto Cão, Tinta Amarela, Touriga Nacional, Tinta Barroca, and Sousão.

The family arrived in the region in 1882 with Andrew James Symington coming from Scotland. He went to work for Graham’s, which had been founded back in 1820. Symington has recently announced the declaration of 2020 Vintage Ports for both Graham’s and Warre’s, celebrating the 200th and 350th anniversary of those houses respectively, although only a couple of hundred cases of both.

In the early part of last century, Andrew Symington was also a partner in both Warre’s and Dow’s. In 1970, his descendants purchased Smith Woodhouse and Graham’s (in yet another nice moment of synchronicity, the Graham’s 1970 Vintage Port is one of the truly great VPs of that superb vintage). Today, a coterie of cousins runs the empire.

Graham’s was originally a textile trading firm founded by William and John Graham, operating in Oporto. The company had been described by one historian of the day as “among the merchant princes of Great Britain.” In 1820, a creditor delivered 27 barrels of Port to cover a debt. The brothers then felt that a change of direction lay in their future and this famous Port house was born.

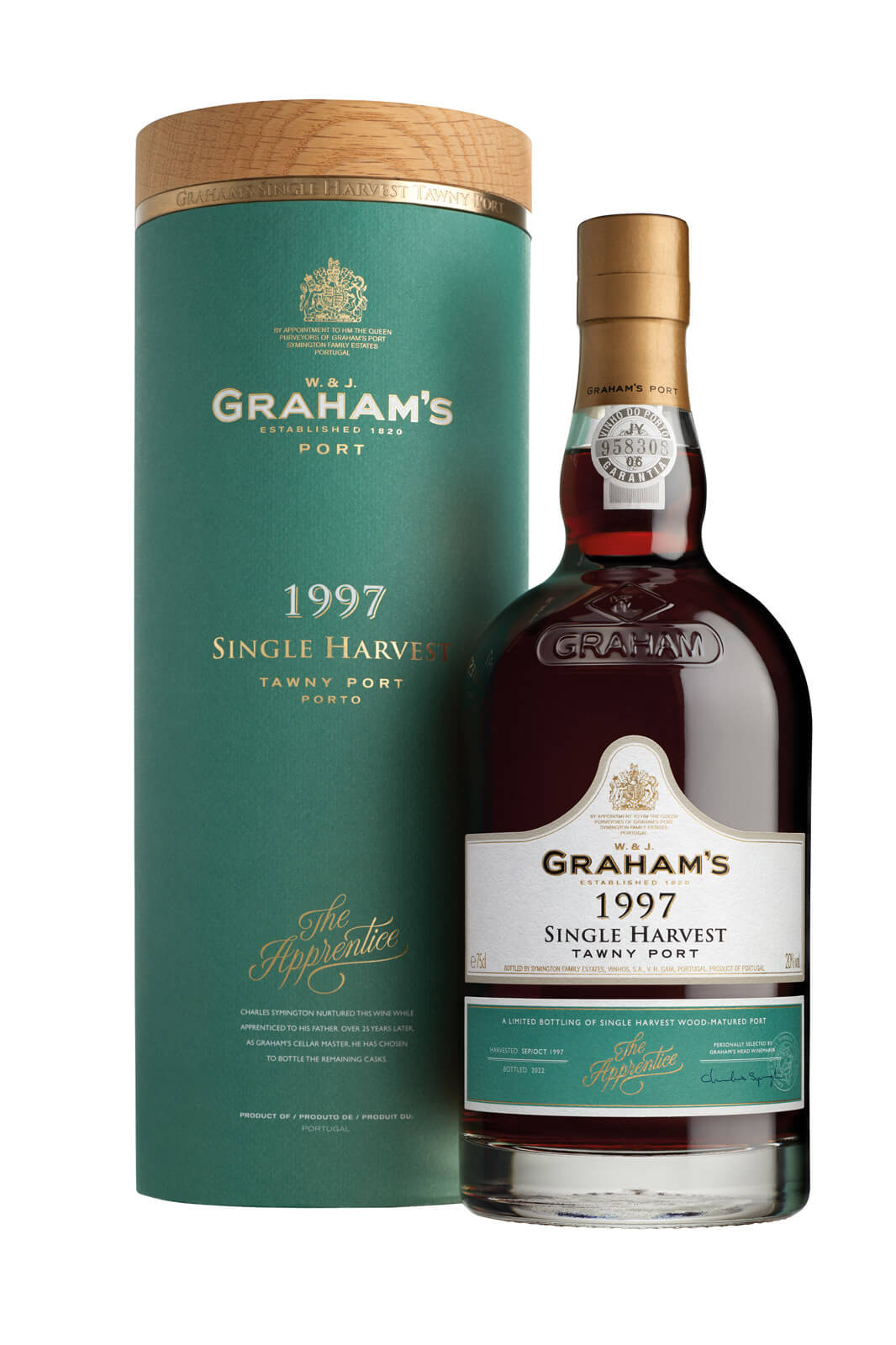

Grahams 1997 Single Harvest Tawny The Apprentice

Graham’s Single Harvest Tawny Ports

Graham’s is undoubtedly better known for sublime Vintage Ports than Tawnies, but it has established its Tawny credentials with their Ten-, Twenty-, Thirty-, and Forty-Year Tawnies. As well as these age statement Tawnies, Graham’s has also moved into Single Harvest releases (the house prefers that term to Colheita, which is less self-explanatory).

Graham’s has a trio called the Cellar Master’s Trilogy comprising The Apprentice, The Artisan, and The Master. The actual vintages of these releases vary from time to time as these things are not endless. Some might only be a single barrel. Currently, we have the 1997 as The Apprentice, having recently replaced the 1994; 1974 as The Artisan; and 1950 as The Master.

The 1997 vintage appeals as it represents the year that current head winemaker, fourth-generation Charles Symington, joined his father Peter in the winemaking team. Fans of Vintage Ports will be aware that both 1997 and 1994 are considered stunning years for that style, but it does not always translate.

If one turns to the port lovers’ bible, Port Vintages by J.D.A. Wiseman (an essential must-have for anyone interested in the subject – I use the first edition published in 2018, though a second edition has now also been released), it is obvious that 1950 was barely better than okay and 1974 excited absolutely no one. But that does not mean that select barrels with long aging can’t make and/or contribute to stellar Tawnies.

The series originally emerged thanks to a request from a good customer. He was keen for a Colheita from Graham’s from 1961 for an anniversary, and the house was happy to oblige. Other vintages have included 1952, 1969, 1972, and 1982 (none of which are widely declared vintages).

The idea of The Apprentice is that the port will be around 25 to 30 years of age. The Artisan is to be 40 to 50 years. Ahead of the 1974, Graham’s had released a 1963 Single Harvest Tawny – now that is a great year for Vintage Port. It is obvious that any attempt to draw correlations between the two styles runs into issues.

For The Master, prior to the 1950 we had 1940. Interestingly, in those days Graham’s did not operate with the concept of a head winemaker.

Grahams 1950 Single Harvest Tawny The Master

All of these Ports are limited in production for obvious reasons, especially The Master – we are talking 400 bottles. Pricing will obviously vary but looking at Winesearcher.com, expect to pay around $200, $500, and $2,000 respectively. If that seems excessive (given the explosion of prices for top wines around the globe, it doesn’t), remember the angel’s share. This is the amount lost to evaporation from barrels over their long periods aging in the cellar. The team at Graham’s estimate 1.5 to two percent over the first ten years, but for a wine like the 1950, 40 to 50 percent.

The 1974 vintage might not have been one for Vintage Ports, but it has great significance in Portugal as the year when the dictatorship that had ruled the country for half a century was finally overthrown. There is a school of thought that says that an otherwise excellent vintage was ignored from the Vintage Port perspective due to the turmoil being experienced by the country, though one would think at least a few houses might have managed to declare. Still, that has now led to stocks available, albeit tiny quantities, for this Artisan Single Harvest.

Nineteen fifty, of course, saw a Europe devastated by World War II attempting to revive, but it meant that keeping large stocks of Port in barrel at the time was not an economic reality. That said, those that they did put away were the very best examples.

Graham’s Single Harvest Tawny Ports: tasting notes

The Apprentice Single Harvest Tawny 1997 – A ruddy brown/orange red in color. An elegant yet intense style of Tawny. Tight and complex with dry herbs, cigar box, orange rind, spices, and raisins. Complex. A little air helps it open up, evolve, and expand. The palate has a hint of bacon fat, cinnamon, white chocolate, and rose petals. The intensity is maintained the full length, which is impressive in itself. 94.

Grahams 1974 Single Harvest Tawny The Artisan

The Artisan Single Harvest Tawny 1974 – A pale Tawny orange, the nose here is more dried fruits with teak and old rancio notes. Orange rind, cherries, spices, toffee, stone fruit, and sandalwood. Concentration and complexity with a wonderfully supple texture. Clean and finely balanced, there is great length to be found here, with the merest hint of sweetness. Lingering finish intertwined with floral notes. A glorious Tawny. 97.

Grahams 1950 Single Harvest Tawny The Master

The Master Single Harvest Tawny 1950 – This Tawny is from a cooler vintage, with the fruit largely sourced from Graham’s legendary Quinta dos Malvedos. What a stunning Tawny this is! The age is immediately apparent in the color, burnt orange with green tinges around the edge. An ancient fortified, not dissimilar to some of the old gems from Rutherglen.

Wonderful elegance, there is a gentle sweetness here. Mocha, coffee bean, cigar box, orange peel, walnuts, fudge, chocolate, spices, and stone fruit. This is concentrated and complex and yet it dances. Incredibly intense, deliriously supple palate, extraordinary length, and it finishes with that amazing peacock’s tail with the explosion of flavors. A great fortified. 98.

For more information, please visit grahams-port.com.

You may also enjoy:

Port Vintage 2016: One Of The Most Declared Vintages Of All Time, A Sensational Year

Taylor’s Trio Of New Vintage Ports: There Will Be Comparative Tastings For Decades To Come

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!