Veuve Clicquot La Grande Dame 2012: A Complete Champagne With Great Balance And Length

by Ken Gargett

If you visit the region of Champagne (a bucket list must if you have not) or even just drink your fair share of the stuff, a term you’ll often hear is “Champagne widows.” These are not like golfing widows or fishing widows where one spouse has been left at home while the other indulges in their various passions. Here, it is meant literally.

Why are they important? Because it is fair to say that without them, the champagne you drink today, and the processes involved, would be very different. And not in a good way.

So who are the Champagne widows?

Madame Louise Pommery is one, Madame Camille Olry-Roederer another. More recently Madame Bollinger. Mathilde-Emilie Laurent Perrier and Odette Pol-Roger are other examples. Veuve means widow in French so the use of that word in the name of a house is a bit of a giveaway: Veuve Fourny, Veuve Doussot, and Veuve Godard are examples.

Historians have even suggested that some houses in the very early days added “Veuve” to their labels to give their champagnes added panache. Historians will also tell you that the production of champagne was one of the very first “industries” (an awful term to use when talking about such an exquisite wine, but you know what I mean) in which women took prominent roles in production.

Barbe-Nicole Clicquot (aka Veuve Clicquot)

All the genuine widows made contributions, and all have wonderful stories, but none match the extraordinary Barbe-Nicole Clicquot (1777-1866). She was, for all intents and purposes, the very first of the Champagne widows. She was certainly the least likely but ultimately the most accomplished. While the house of Veuve Clicquot is one of the very largest of all today and is now part of the LVMH empire, her achievements have benefited every producer in the region.

I will touch on them, but anyone wanting to know even more should look to the wonderful book by Tilar Mazzeo called The Widow Clicquot from 2008.

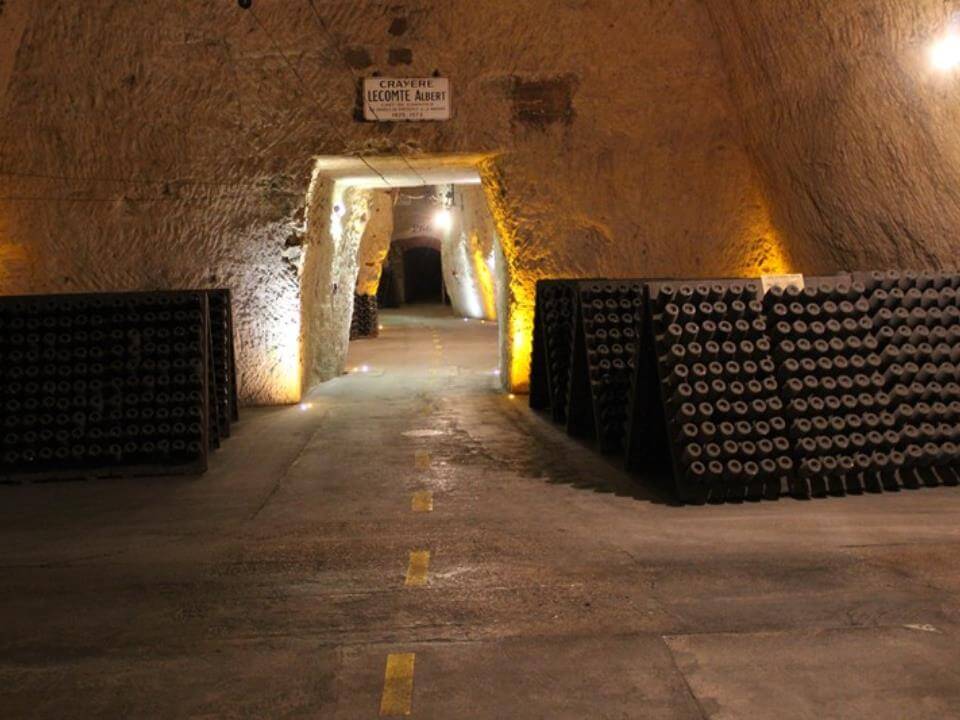

Veuve Clicquot’s cellars

Barbe-Nicole Clicquot

At the very beginning of the nineteenth century, the youthful François Clicquot ran one of the major champagne houses, a position he had inherited from his father, who had established it around three decades earlier. Shortly after the harvest in 1805, François unexpectedly dropped dead, leaving the house in the hands of his even younger and completely inexperienced widow, Barbe-Nicole, who was just 27. At the time, they were making just 100,000 bottles annually.

Veuve Clicquot vineyards

Given the prevailing attitudes of the day, the fact that Barbe-Nicole had no real experience in the champagne industry, let alone any general business experience, and the overwhelming advice to her to sell, it came as a complete shock to everyone when she announced that she had no intention of offloading the family business and that she would run it. I doubt there was a single person in the region who gave her the slightest chance of success. Little did they know!

For more than 60 years (she passed away at 89, still working), she guided the house to glory. When she passed, the production had grown to 750,000 bottles annually. Today, production would probably be not too far short of 20 million bottles.

Years later, she would be described as the first businesswoman in France and possibly Europe. She proved to be resilient and tough as well as visionary. Barbe-Nicole threw herself into the business, learning as fast as possible. She opened up markets in Russia and subsequently the United States.

Some of her achievements might be debated as often these things are evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, and houses find all manner of ways to twist history for their purposes, but among the great legacy she left are such contributions as the first rosé champagne ever made and moving to the style of bottle we still see today rather than a much chunkier one. She is also attributed with creating the first vintage champagne in 1810.

Although it had long been claimed that Veuve Clicquot made the first rosé champagne, there is now evidence that it was more likely to have been Ruinart. Clicquot’s records suggest that the house began offering rosé champagne from 1775, but recent documentation confirms that Ruinart shipped some as early as 1764. As both houses are now part of the LVMH empire, it is probably not going to be a heated argument. What is not clear is how Ruinart made its rosé (and indeed Clicquot at that time as this was, of course, before Barbe-Nicole’s ascension), whereas the method of blending in some red wine is attributed to Mme Clicquot in 1818. It is likely that prior examples came from skin contact, possibly inadvertently.

Impressive staircase to the champagne cellars of Veuve Clicquot

Riddling

Perhaps Barbe-Nicole Clicquot’s greatest contribution was the process of riddling. Making champagne involves a second fermentation in the bottle, which is what gives the wine its sparkle (the CO2 from that second fermentation is trapped in the bottle and, when opened, escapes by way of bubbles). The problem was that the fermentation left unsightly sediment – dead yeast cells. This, the yeast lees, is very important in giving the wine its character while it is aging, but if left in the bottle it makes the wine cloudy and murky.

Legend has it that one evening Barbe-Nicole and her cellar master tipped the Clicquot kitchen table over on its side and drilled holes in it. The bottles with the lees were put in the holes and then rotated a little every day for several weeks until they were effectively upright (upside down) and the lees had gathered at the base of the temporary cork (which was at the bottom as the bottle was inverted). The procedure can’t be done in one movement as that causes some lees to stick to the sides of the bottle.

The bottle is then dipped in an extremely cold brine solution (and if you are ever so silly as to stick your fingers in the solution to find out just how cold it is – guilty! – you will find it most definitely is frostbite stuff), which freezes that plug of dead yeast. The cork is flicked off, the plug shoots out like a bullet (this is called disgorging), and the dosage added (dosage is usually a house secret but will include some sugar to bring the wine to the level the chef de cave requires as well as a tiny top-up of wine), and the final cork is then inserted. This all happens in the blink of an eye.

Suddenly the champagne was sparkling clear. No more sludge, sediment, cloud, or muck. This was revolutionary. Every champagne house has since been the beneficiary.

It was then inevitable that the house would honor Madame Clicquot by naming its prestige cuvee after her – Veuve Clicquot’s La Grande Dame (often just called “LGD”). She was considered the grand dame of Champagne. LGD was first made from the 1962 vintage, just 6,000 bottles, but it was the 1966 vintage that was first released commercially in 1972, the year of Veuve Clicquot’s bicentenary. That was also the year the house founded the highly prestigious Veuve Clicquot Business Woman Award.

Veuve Clicquot La Grande Dame 2012

Veuve Clicquot has always been a “Pinot house,” and this has never been more evident than with recent releases of La Grande Dame.

Veuve Clicquot already makes one of the most loved and recognizable champagnes in the world with its famous non-vintage – yes, the yellow label. For me it is one of the most underrated non-vintage (multi-vintage is a better expression but not sure we are quite there yet) champagnes available. And it is even better if you can slip it away in the cellar for a couple of years.

Veuve Clicquot La Grande Dame 2012

The Vintage champagne is always exceptional. Former chef de cave Dominique Demarville moved against the trend by deciding to release no more than three vintages a decade but he has moved on and his former colleague at Mumm, Didier Mariotti, has taken over. The trauma of losing a talent like Demarville was softened by the arrival of another of the region’s very best in Mariotti. A fortunate house, indeed. Remarkably, Mariotti is only the eleventh chef de cave for the house, which was founded in 1772.

As mentioned, he took over from his friend Demarville, who became chef de cave on the retirement in 2009 of another famous name, Jacques Peters, from the Pierre Peters family. Jacques was also mentor to another of the region’s stars, Cyril Brun, now chef de cave with Charles Heidsieck.

Grape picking at Veuve Clicquot

The 2012 La Grande Dame was made by Demarville but now falls to Mariotti. It is worth noting that there is a second version – though the same wine – in a presentation bottle and case created for the house by Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama. Trust me, you won’t miss it. It is anything but the shy wallflower of champagnes. Pricing is around £160 in comparison with £120 for the normal bottle.

The 2012 La Grande Dame is the first release of this wine since the magnificent 2008. It was the 2008 that really stressed the Pinot path for the house, being a whopping 92 percent Pinot Noir, the majority coming from estate vineyards. The 2012 drops back to 90 percent Pinot Noir. Madame Clicquot was a great believer in the use of Pinot Noir, believing this led to the best champagnes. The team prefers the more northerly Pinot vineyards as these are considered to produce more elegant champagnes. The star vineyards are in Verzy, Verzenay, Bouzy, and Ambonnay in the Montagne de Reims and Aÿ in the Vallée de la Marne. The Chardonnay incorporated into the wine is from Le Mesnil and Avize in the Côte des Blancs. Dosage is six grams/liter.

This year is the house’s 250th anniversary and the fiftieth anniversary of the first release of La Grande Dame. I have no doubt that Madame Clicquot would be very proud of what the team has achieved, not only with this wine but with the house.

Veuve Clicquot La Grande Dame 2012: tasting notes

For me, the 2012 La Grande Dame is a special champagne. It walks the tightrope between dense and coiled power with delicacy, finesse, and elegance. Great intensity, finally balanced acidity, early complexity, and is still wonderfully youthful and with such a long future ahead of it. There is a brief, initial smoky note that morphs into raspberries, florals, jasmine, spices, hazelnuts, stone fruits, a hint of citrus, and even a whiff of mint and coconut husk. Great balance and such length.

Veuve Clicquot La Grande Dame 2012

There really is little to suggest it is such a Pinot-dominant champagne. This can be cellared for ten to 20 years, longer in a good cellar, with confidence. A complete champagne. 97.

Finally, something truly special. When Mariotti headed to Brisbane to present the new release, he kindly slipped a few very special magnums into his luggage for friends. Magnums of the recently disgorged 1990 La Grande Dame, direct from the cellars at Veuve Clicquot. If this gives a glimpse of what is in store for those with the 2012 in their cellar, then I am seriously underestimating that wine. This was simply one of the greatest champagnes one could ever wish to drink.

Gold in color, it was wonderfully aromatic with honeysuckle, peaches, quince, beeswax, white chocolate, liquid honey, and lemongrass. Incredibly complex, it was bright, alive, finely balanced, and with great length. Layered, elegant, and with two decades at least ahead of it, this was a monumental champagne. Even better, this can be ordered from the house for around AUD$1,500 per magnum. Expect these bottles to be severely limited in quantity. 100.

You may also enjoy:

Pommery Cuvée Louise Champagne And The Invention of Brut

Bollinger RD 2004: When It Came To Champagne (And Much Else), Madame Bollinger Had Excellent Taste

Pol Roger Sir Winston Churchill 2012 Champagne: It Matches The Hype. And Then Some

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!